Книга: Английский язык. Практический курс для решения бизнес-задач

Назад: Lesson 30 Fixed Income Securities

Дальше: Essential Vocabulary

A Stock Buyer’s Guide to Bond Investing

Some Bond Market Basics

As a stockholder, you are a part owner of a business, able to enjoy the unlimited upside potential – or downside risk – associated with a particular company. A bondholder, on the other hand, is a creditor, and bonds are known as debt securities.

When you purchase a bond, you are essentially lending money for a specific period of time, at a fixed rate of interest. Bonds are generally considered a more secure investment than stocks since bondholders have a senior claim to a company’s assets in the event of a corporate restructuring.

Bonds are issued by both the public and private sector. The former includes the U.S. government, as well as state and local municipalities. The latter comprises both privately held and publicly traded corporations. Bonds are a reliable alternative to banks and other lenders who might demand less attractive financing terms than the capital markets are able to provide, such as a higher rate of interest. Ultimately, this cost saving benefits both taxpayers and shareholders by lowering the borrower’s overall expenses.

Bonds are generally known as fixed-income securities since they pay a fixed rate of interest. As a result, falling interest rates make outstanding bonds more attractive, while conversely, rising interest rates cause fixed-income securities to lose principal value. Many investors like bonds because regardless of a bond’s fluctuating price during its lifetime, the principal of the bond is returned at face value when it matures.

Bonds of equal credit quality will generally provide investors with higher rates of return as maturity lengthens, since it is considered riskier to hold longer-dated securities than short-term instruments. Investors are also rewarded with progressively higher rates of return as credit quality declines to compensate for the additional risk.

Callable and Bullet Structures

Callable and bullet structures are common to most fixed-income securities. Bond issuers sell redeemable debt, known as callables, in order to give them the flexibility to purchase – or call – the bonds prior to maturity after a specified date. This makes good economic sense for the issuer in a falling interest rate environment since it then allows them to reissue the same amount of debt at a lower interest rate. However, if and when the securities are called, investors are handed back their original investment in cash and are faced with the less attractive option of reinvesting it in lower-yielding, higher-priced securities. This is known as reinvestment risk.

For investors determined to avoid reinvestment risk, noncallable bullets may be purchased. Bullets are bonds with a fixed maturity date and no call provisions. Though the rate of return on bullets will generally be lower than callable securities, the issuer cannot compel the bondholder to redeem the security prior to maturity.

Governments

The majority of public sector debt is issued by the federal government. The size of the market has rapidly contracted in recent years as the budget surplus continues to bolster buybacks of outstanding securities and promotes the reduction of new supply. Interest paid to holders of Government securities is exempt from state and local taxes.

Treasury Securities

Since the U.S. Treasury Department issues most government securities, bonds in this sector are commonly referred to as Treasuries. Given the remote possibility that the U.S. would ever default on its obligations, Treasuries are considered to be the safest of all fixed-income securities and serve as the benchmark utilized by bond investors .

The four most popular types of fixed-income securities issued by the U.S. Treasury are Bills, Notes, Bonds and TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities). Bills have maturities of three months to one year, and are sold at a discount since the interest rate is equal to the difference between the purchase price and the principal amount an investor would receive at maturity (interest basically accrues to face value rather than being directly paid out to investors). Notes pay interest semi-annually and are issued in two-year, five-year and ten-year maturities. Bonds are issued with 30-year maturities and also pay semi-annual interest. TIPS provide bond investors with a hedge against inflation since they pay an interest rate that is periodically adjusted according to changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

U.S. Treasury STRIPS (Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities)are also a popular government investment. Much like bills, STRIPS are sold at a discount to face value, since the interest accrues to the face value of the security rather than as a semi-annual payment to the bondholder. Unlike bills, though, STRIPS offer investors a wide range of longer-dated maturities to choose from.

Agencies

U.S. federal agencies, which are fully owned by the U.S. government, and Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), which are privately owned entities created by Congress, together issue debt securities known as Agencies. This implicit connection to the federal branch has led Agency structures to be considered second in quality only to U.S. Government securities. Agencies use the proceeds raised in the capital markets to provide funding for public policy purposes, such as housing, education and farming.

GSEs are the most active issuers in the Agency market. You might be familiar with the two largest shareholder-owned companies: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Mortgages

Mortgage-backed securities, commonly known as mortgages, are bonds created from mortgage loans. These loans are originated by a variety of financial institutions in order to provide financing for home loans and other real estate. Mortgage lenders typically package, or «pool», these loans and then sell them to mortgage-backed securities issuers. The bonds are generally issued in multiples of $1,000.

At approximately $2.5 trillion in outstanding securities, mortgages are now a major segment of the US bond market. Mortgage bonds generally retain high credit quality since most are either explicitly, or implicitly, backed by the federal government.

Mortgage securities are generally classified as either pass-throughsor Collateralised Mortgage Obligations (CMOs). Pass-throughs basically collect mortgage payments from homeowners and pass this cash flow onto investors. CMOs provide a more predictable payment stream than pass-throughs by creating separate «tranches», designed to meet different investment objectives.

Corporates

Public and private companies issue corporate bonds, commonly known as corporates in order to meet both short– and long-term financing needs. The proceeds from a bond sale are therefore used for a wide variety of purposes, such as for the purchase of new equipment, the funding of general operating expenses or for the financing of a company M&As. Corporates are typically issued in multiples of $1,000, have a maturity range between one and 30 years and pay semi-annual interest. The vast majority of corporate bonds are fully taxable.

Corporate Bond Credit Quality

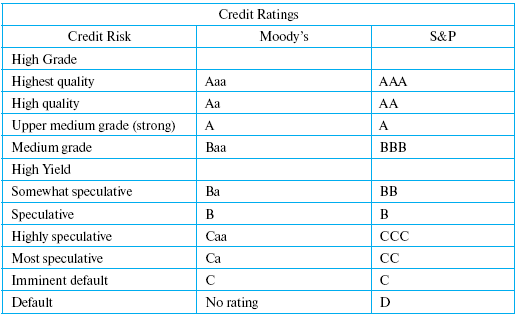

Credit quality is the most important concern for corporate bond investors. Most corporates are assigned credit ratings by Moody’s and S&P. These ratings classify an issuer as «high-grade» or «high-yield». High-grade bonds are considered fairly conservative investments since these companies are deemed to be in good financial health and are unlikely to have trouble meeting their debt obligation. These bonds are rated from «Aaa» to «Baa» by Moody’s, and from «AAA» to «BBB» by S&P.

High-yield bonds are considered speculative since they are issued by companies with more credit risk. These bonds are rated on a scale from «Ba» to «C» by Moody’s, and from «BB» to «D» by S&P. These bonds pay a higher rate of interest – and have a potentially higher rate of return – than their high-grade counterparts. However, high-yield bonds are only appropriate for risk-tolerant investors.

Municipals

States, cities, counties and towns issue municipal bonds. The proceeds from bond sales are used for the building and maintenance of a variety of public works projects – such as for the construction of schools, roads, hospitals and sport stadiums.

There are two types of municipal securities: General Obligation (GO) and Revenue Bonds. GOs are backed by the full taxing authority of the issuer, while Revenue Bonds are backed by the income generated from the project being financed.

Since municipalities can vary in credit quality, most municipal bonds are assigned a credit rating from either Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s. However, municipal buyers have the luxury of opting for no credit risk. Today, approximately 40% of all new issuance is «insured» by a major municipal bond insurance company. Insured bonds automatically receive the highest «AAA/Aaa» ratings since the insurance company guarantees that if a municipality is not able to meet its debt obligations, it will provide the payments of principal and interest.

Municipals are not taxed by the federal government, and are generally exempt from state and local taxes for residents of the issuing state. Since municipals are exempt from federal income taxes, investors in the 28% tax bracket or above would typically receive better returns with municipal bonds in their taxable accounts than with other higher-yielding, taxable fixed-income securities.

Certificates of Deposit

Certificates of deposit, or CDs, are time deposits issued by a bank, which pay a fixed rate of interest for a specified period of time. Since CDs are FDIC-insured, up to a maximum of $100,000 (per depositor, per financial institution, including principal and interest combined in each insurable legal capacity), credit risk is not a concern. CDs are generally offered in multiples of $1,000, while «Jumbo» CDs are sold in $100,000 denominations. CDs may also contain call provisions. CDs may be purchased directly from a bank or brokerage firm.

Putting It All Together

There is only one way to begin building a bond portfolio that is right for you. In fact, it is no different from the advice that you might receive if you decided to construct a stock portfolio: Start with a plan that works.

The best strategies for bond investors are the laddered portfolio and the diversified portfolio approach. Regardless of the shape of the yield curve, your interest rate outlook or the performance of a particular sector, these two basic strategies will help prepare the proper foundation to meet your specific financial objectives.

In a laddered portfolio, bonds mature in sequence over a period of years. As each security matures, the proceeds are reinvested in the longest maturity «rung» of the ladder. This is a rather conservative approach, but it is widely and successfully employed by individual investors since it minimizes reinvestment and interest rate risk.

You may also construct a diversified portfolio. This method uses a wide variety of bond classes and structures. This approach is designed to garner incremental yield by taking on a variety of risks – many of which tend to cancel out one another over time.

Source: SalomonSmithBarney, 2002,

Назад: Lesson 30 Fixed Income Securities

Дальше: Essential Vocabulary