What Happens If You Don’t Mock Write-Host: If you were to

comment out this line and not mock Write-Host, the actual Write-Host

cmdlet would be invoked when your tests run. As a result, you would see the Write-Host output on your screen, which can clutter your testing

results and make it more challenging to isolate the actual test outcomes from extraneous console messages. (Figure shows the extraneous messages that were not suppressed, cluttering the test results.)

Figure 9-1. Unwanted “noise” can make it difficult to read test results So, by including this mock without specific replacement actions, you

ensure that Write-Host stays silent during testing, keeping your test results clear and focused on the behavior of your function.

Describe Block

Describe "Invoke-FileOperation function" {

...

}

The Describe block provides a logical grouping for your tests and serves as a descriptive label for what you’re testing. In this case, it describes the testing of the “Invoke-FileOperation” function.

130

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Context Blocks

Context "When the file exists" {

...

}

Context "When the file does not exist" {

...

}

Within the Describe block, we have two Context blocks. Each Context represents a different scenario that we want to test:

– The first context, “When the file exists,” simulates a

scenario where the specified file exists.

– The second context, “When the file does not exist,”

simulates a scenario where the specified file is missing.

So far so good? It’s all ground we’ve already covered in previous

chapters. Now on to the good part.

IT Block

It "Should process the file" {

...

}

It "Should handle the missing file" {

...

}

Inside each Context block, we have It blocks. Each It block represents a specific test case or assertion. They specify what the expected behavior should be for the given scenario.

131

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

In the first It block, we test that when the file exists, the function should process it. We use the Mock cmdlet to control the behavior of Test-Path, and we expect the result to be True using Should -BeTrue.

In the second It block, we test that when the file does not exist, the function should handle the missing file. Again, we use the Mock cmdlet to simulate Test-Path, and we expect the result to be False using

Should -BeFalse.

So we have effectively tested our code logic by simulating different

file existence scenarios, ensuring that our Invoke-FileOperation

function behaves as expected under both file existence and nonexistence conditions.

These Pester tests ensure that your Invoke-FileOperation function behaves correctly under different file existence scenarios, all without actually touching the real file system.

A Little More Between the Curly

Braces, Please

When using Mock, the portion between the curly braces { and } defines what the mock will return. As you observed in the earlier example Mock Test-Path { Return $true }, when Test-Path is called and replaced

by the mock, it returns $true. Your code, in turn, interprets this result as if Test-Path genuinely returned $true, and it proceeds based on that

response.

However, you can also use the curly braces to return nothing,

effectively silencing the command being mocked. This is similar to what we did when we mocked Write-Host. Leaving out any content between the

curly brackets, like in Mock-Write-Host { }, achieves the same result – the mocked command is silenced, and it doesn’t produce any output or return any values.

132

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

So, the content between the curly braces defines what the mock

returns, and you can use this to control the behavior of the mocked

command, whether it’s returning specific values or producing silence

during testing.

Mocking Best Practices

The golden rule of mocking: Mimic reality, but don’t go overboard. Think of it as imitating a chef’s recipe; you want the taste to be authentic, but you don’t need to replicate the entire kitchen.

In our previous example of mocking Test-Path, how did I know to

mock the return as true or false? I simply looked at PowerShell’s Help Test-Path and unearthed this gem: "The ‘Test-Path’ cmdlet determines whether all elements of the path exist. It returns ‘$True’ if all elements exist and ‘$False’ if any are missing."

You can also dump the return in a variable and inspect its contents to see the type of data being returned, use GetType() or pipe to Get-Member if you need to find out the object type. I usually end up with my mocks returning a hashtable in most cases though, and you’ll see this shortly.

Now, here’s the trick: while you aim to mirror the real command, you

don’t need to mimic every nook and cranny. Imagine you’re crafting a

sculpture; you chisel away only what’s necessary to reveal the masterpiece within. Test-Path was easy; it returns a Boolean, and that’s it but take something like Get-ADUser, for instance; it spills out a treasure trove of properties, but maybe you need only a handful, so simply return the ones you need.

So, as we journey forward, keep this balance in mind. Our mocks

should echo reality but be tailored to suit our specific needs.

Here’s a handy list I put together of some mocking best practices that I try to follow and that you should also consider when creating your mocks: 133

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

1. Mimic real behavior: Mock commands as close to

their real behavior as possible. Understand the real

command’s outputs and behaviors by referring to

official documentation or help files. By replicating

real- world responses, your tests reflect actual

application scenarios more accurately.

2. Keep it simple: While it’s essential to mimic real

behavior, don’t overcomplicate mocks. Focus on the

specific behavior your code interacts with. Complex

mocks can make tests convoluted and harder to

maintain.

3. Be consistent: Maintain consistency in your

mocks. If you mock a command in one test

scenario, use similar patterns in other relevant

scenarios. Consistency enhances the readability and

comprehension of your test suite.

4. Update mocks with code changes: When your

actual code changes, ensure that corresponding

mocks are updated. Mismatched mocks can lead to

inaccurate tests, providing a false sense of security.

5. Avoid tight coupling: Mock only what your code

directly interacts with. Avoid overly tight coupling

where a change in the underlying implementation

forces extensive changes in your tests. Mocking

should shield your tests from implementation

details.

6. Documentation is your friend: Rely on official

documentation, help files, and specifications when

determining how to mock specific commands.

Understanding the intended behavior helps create

accurate mocks.

134

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Beware of Pitfall #5 in the preceding list – steering clear of tight coupling. in my initial foray into the realm of mocking, i meticulously mocked every detail, down to the precise messages emitted by Write-host. (You’ll see how later.) however, when i subsequently altered the message text within my functions, chaos ensued. all my tests came

crashing down like a house of cards.

By adhering to these best practices, your tests become powerful tools

for ensuring your code’s correctness, resilience, and maintainability. Now that you have a strong foundation, let’s continue this lengthy chapter, building on the principles you’ve learned so far.

Mocking Complex Cmdlets

By now, you’ve mastered the art of mocking straightforward commands like Test-Path. You’ve gained the confidence to manipulate their behaviors, crafting your tests with finesse. But what about the more complex cmdlets, the likes of get-aduser, Invoke-RestMethod, or Import-Csv? These

multifaceted tools don’t merely return true or false; they churn out intricate data structures, arrays, and hashtables.

Fear not, for the Mock cmdlet is still your trusty companion on

this journey. It possesses incredible depth beyond the binary world of true and false. Within those curly braces, you can conjure a universe of possibilities – a PSCustomObject, an Array, a Hashtable, or even an array of hashtables, and the list goes on.

Once I had personally figured this part out, my mocking prowess

evolved from Billy-Basic to Henry-Hero. Suddenly, there was nothing in the PowerShell realm that I couldn’t mock, no complexity too great to

simulate.

135

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Stay with me, and I’ll guide you through this transformation. Together, we’ll unravel the secrets of mocking these intricate cmdlets, empowering you to wield PowerShell’s mightiest tools with finesse. After perusal of the next few pages, you will be stepping confidently into the realm of Henry-Hero mocking.

PSCustomObject

Imagine you have a function called Get-ServerInfo. Its job? Reading data from a CSV file and doing something with it. Simple, right? Well, reality often throws curveballs – the CSV file you’re expecting might not be there on the computer running your tests.

But here’s the catch: we don’t really care about the CSV file itself; as just alluded, the test may be run on a system that does not have access to the real CSV. We just want to know what our function does with the data.

And here’s where PSCustomObject becomes your buddy.

PSCustomObject can help you pretend that your function imported

data from a CSV file, even if it didn’t really. It’s like giving your function imaginary data to play with. How? Well, you create a pretend data set

like this:

$MockedData = @(

[PSCustomObject]@{

Property1 = 'Value1'

Property2 = 'Value2'

# ...add more properties if needed

}

)

Mock Import-Csv { return $MockedData }

136

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

With this trick, your function can keep chugging along, imagining it’s working with real data. PSCustomObject ensures your tests stay smooth

and predictable, even when the real world throws a few surprises your way.

it’s worth noting that i’ve enclosed the entire [PSCustomObject]

and its properties in brackets so that it becomes an array of

pSCustomobjects: @([PSCustomObject]...). this setup allows

you to create more than one “row” in your simulated CSV by adding

additional pSCustomobjects. essentially, it becomes an array of

pSCustomobjects. if your needs are simpler and you only require one

custom object, you can omit the brackets entirely. Flexibility is the

key here – tailor your approach to match the complexity of your data

simulation needs.

Let me show you what I mean with an example:

function Get-ServerInfo {

$servers = Import-Csv -Path 'C:\OHTemp\Servers.csv'

return $servers.count

}

The function reads in a CSV file and returns the number of servers

found in the CSV file. Not very practical in the real world but good enough to hammer home the concept here. Listing demonstrates how a test could look for it.

Listing 9-3. Testing the Get-ServerInfo function

Describe 'Get-ServerInfo' {

Context 'When given a valid CSV file' {

It 'Returns the correct number of servers' {

#Arrange

137

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

$MockedData = @(

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = 'Server1'

OS = 'Windows Server 2019 Standard'

};

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = 'Server2'

OS = 'Windows Server 2012 R2'

}

)

mock Import-Csv { $MockedData }

#Act

$expected = Get-ServerInfo

#Assert

$expected | Should -Be 2

}

}

}

remember, when the test calls the function Get-ServerInfo and

Import-CSV is executed, it swaps it out for your mocked Import-Csv

and mocked data. the real Import-Csv is never called within your

function. Clever stuff!

138

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

There’s More Than One Way to Skin a Cat

Now, let’s explore an alternative approach when dealing with CSV files, revealing the versatility of Pester and encouraging you to think “outside the box” when crafting your tests.

Consider this: what if we achieve the same test results using

ConvertFrom-CSV and a here-string to simulate the CSV data? Let’s take a peek at how this scenario unfolds in the script snippet in Listing .

Listing 9-4. An alternative method

Describe 'Get-ServerInfo' {

Context 'When given a valid CSV file' {

It 'Returns the correct number of servers' {

#Arrange

mock import-csv {

ConvertFrom-Csv -InputObject @'

'Name','OS',

'Server1','Windows Server 2019 Standard'

'Server2','Windows Server 2012 R2'

'@

}

#Act

$expected = Get-ServerInfo

#Assert

$expected | Should -Be 2

}

}

}

139

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

This alternative method not only showcases the power of Pester but

also prompts you to consider innovative solutions when shaping your

test cases.

Hashtables

When it comes to my mocking adventures, I often find myself relying on hashtables. Much like with PSCustomObjects, I encapsulate them in an

array by wrapping them in brackets: @().

Let’s dive into an example, shown in Listing , where we mock Get-Module using an array to simulate the return of multiple versions of the same installed PowerShell module.

Listing 9-5. Mocking Get-Module

Describe 'My Pester test' {

It 'does something wonderful' {

#Arrange

Mock Get-Module {

@{ Version = '1.0.9'; Name = 'MyModule'}

@{ Version = '1.0.5'; Name = 'MyModule'}

@{ Version = '1.0.2'; Name = 'MyModule'}

}

# Act...

# Assert...

}

}

In this scenario, the use of hashtables within an array enables us to

brilliantly mimic the behavior of Get-Module, returning various versions of the same module.

140

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

It’s all about crafting your mocks to mirror the real-world scenarios, ensuring your tests are as robust as your imagination allows.

When to Use a PSCustomObject over a Hashtable

Knowing when to opt for a PSCustomObject over a hashtable is pivotal in PowerShell scripting. As a personal preference, I usually resort to arrays of hashtables. They’re simple to create, easy on the eyes, and universally comprehensible. However, there are situations that call for the elegance of a PSCustomObject.

If a cmdlet produces a PSCustomObject as its output, I follow suit.

Consistency is key; if the cmdlet provides data in this format, it makes sense to mirror it. Furthermore, if your scripting ventures lead you to the realm of strongly typed properties – where a property must be explicitly defined as a certain data type (like string or int) – PSCustomObject

emerges as the hero.

Consider this scenario: you need to define properties like this.

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = [string]"John" # Name property is

explicitly defined as a string

Age = [int]30 # Age property is

explicitly defined as an integer

}

Or you may need to return a specific type of object and for that

PSCustomObject wins again with its PSTypeName Declaration:

[PSCustomObject]@{

PSTypeName = WhateverObjectTypeYouNeed

Name = 'MyName'

}

141

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

In such cases, PSCustomObject becomes your trusted companion. Its

ability to accommodate well-defined data types ensures precision in your scripts.

Import-CliXML

The Import-CliXML cmdlet presents a powerful mocking technique,

especially for scenarios involving API calls. Whenever I saw Pester

examples using API calls I always thought they were bad examples as I

had never needed to use them. One career change later and whammo!

Suddenly, a wave of PowerShell API tasks flooded my workspace, proving that you never quite know what challenges lie ahead. So it would therefore be remiss if we did not include API mocks in our examples too.

Traditionally, mocking API calls involved intricate maneuvers.

However, a straightforward method emerged: calling the API for real and capturing its response in an XML file. This captured “snapshot” could then fuel our mocks, ready for testing. Allow me to illustrate.

Consider a function shown in Listin

Listing 9-6. Example function using an API call

function Get-ThingToDo {

$result = Invoke-RestMethod -Method Get -Uri

"https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity"

if ($result.type -eq "Relaxation") {

return $true

} else {

return $false

}

}

142

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

In this function, the real API response is captured in the $result

variable. If the ‘Type’ property is “Relaxation,” it returns True; otherwise, it returns False. To mock this response, ensuring precise outcomes without real API calls, we employ Import-CliXML.

Firstly, we need to capture a real response. To capture the API

response, simply pipe Invoke-RestMethod to Export-Clixml, as

demonstrated in Listing .

Listing 9-7. Capturing the real API response for later use Invoke-RestMethod -Method Get -Uri

"https://www.boredapi.com/api/activity" |

Export-Clixml C:\OHTemp\Response.xml

This command generates an XML file at the specified location, ready

for use in our mock. In Listin, we integrate this captured response into our test.

Listing 9-8. Integrating the captured API response into the mock Describe "Get-ThingToDo" {

it "Should return True if Type is 'Social'" {

Mock Invoke-RestMethod {

Import-Clixml "C:\ohtemp\Response.xml"

}

$Expected = Get-ThingToDo

$Expected | should -BeTrue

}

}

143

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

In this way, we harness the real-world API response to create mocks,

ensuring accurate and reliable tests. It’s a testament to the adaptability of PowerShell and Pester, empowering us to handle unexpected challenges

with finesse.

.Net Classes

Now, let’s delve into the scary world of .Net classes to demonstrate the flexibility of mocks. Consider a scenario where you’re working with

Invoke-WebRequest and want to specifically catch errors generated by

[System.Net.WebException] within a try-catch block. The function,

defined in Listing , looks like this.

Listing 9-9. The Get-Error function to be tested

Function Get-Error {

try {

$response = Invoke-WebRequest -Uri "https://

fearthepanda.com/notexist" -Method

get -ErrorAction stop

} catch [system.net.webexception] {

write-host "The error was $_"

return 1

}

}

In this function, the catch block targets errors of type [System.Net.

WebException] and returns 1. The corresponding Pester test, found in

Listinures this behavior is as expected.

144

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Listing 9-10. Testing error handling

Describe "Get-error" {

it "Should return 1" {

$webException = New-MockObject -Type System.Net.

WebException

Mock Invoke-WebRequest {

throw $webException

}

Mock write-host

$Expected = Get-Error

$Expected | should -Be 1

}

}

Within the It block, the Mock command simulates the Invoke-

WebRequest call. It uses New-MockObject to create a System.Net.

WebException object with the default error message and then throws the

[System.Net.WebException] to replicate the real scenario of Invoke-

WebRequest encountering an error. This mock ensures the Get-Error

function handles [System.Net.WebException] as anticipated, returning 1.

In general, you would employ New-MockObject to create a mock

object based on the .Net Type, a topic that falls outside the scope of this book. While diving deeper into mocking .Net classes can get intricate and complex, this glimpse should pique your curiosity, encouraging you to

explore this topic further and gain a deeper understanding.

145

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

But Wait, There’s More!

So, .Net can be a bit of a maze, right? But fear not, you don’t have to get lost in it. There are tricks to navigate these complexities, and I’m here to share a couple of them with you.

1. Embrace Native PowerShell: Why complicate

things with .Net when PowerShell itself can often

do the job? Take the example of retrieving the

environment variable windir. Sure, you could use

the .Net approach:

[Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable('windir')

But then you’re setting yourself up for a headache when it’s time

to mock it in your tests. Instead, opt for the native PowerShell

equivalent:

Get-Item -Path 'env:windir'

Simple, elegant, and best of all, easily mockable in your tests. No

more wrestling with .Net intricacies.

2. Wrapping .Net Commands in PowerShell

Functions: A Mocking Strategy: Now, what if

you can’t find a native PowerShell alternative?

Don’t worry, there’s a workaround. Wrap the .Net

command in a cozy PowerShell function. Let’s

say for some reason you just have to fetch an

environment variable using .net. Simply wrap it in a

function as shown in Listin.

146

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Listing 9-11. Encapsulating a .net command within a function Function Get-EnvironmentVariable {

[cmdletbinding()]

param (

[string]$Variable

)

$envVar = [Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable($Variable)

if (-not ($envVar)) {

Write-Host "$Variable not found"

return 1

} else {

return $envvar

}

}

In this concise function, the intricate .Net call is encapsulated,

providing a clear interface. This not only enhances readability but also renders mocking a seamless endeavor during testing.

Let’s illustrate this concept further with an example. Imagine you have a function, as demonstrated by Listing

Listing 9-12. Sample function

Function My-AmazingFunction {

param (

[string]$EnvVar

)

if ($EnvVar) {

$result = [Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable

($Variable)

147

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

return $result

} else {

Write-Output "You didn't want to get the environment

variable"

return $false

}

}

In the initial script, Listine encounter a common problem: direct invocation of a .Net command within the function. Specifically, the line:

$result = [Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable($Variable)

While this approach may seem straightforward, it poses a significant

challenge during testing. When attempting to unit test this function, a crucial problem emerges: the .Net method [Environment]::GetEnvironment

Variable($Variable) directly interacts with the operating system, fetching environment variables in real time. In the realm of testing, unpredictability becomes the enemy. We can’t guarantee the existence or values of these variables in different environments.

This unpredictability creates a testing nightmare. How do we write

reliable tests when the function’s behavior depends on external, ever-

changing factors? Enter the need for a solution: Listin.

Listing 9-13. Refactor the function to easily test .Net Function My-AmazingFunction {

param (

[string]$EnvVar

)

$result = Get-EnvironmentVariable -Variable $EnvVar

148

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

if ($result -ne 1) {

$result

} else {

Write-Host "You didn't want to get the

environment variable"

return $false

}

}

Understanding the Transformation:

In Listin, the script undergoes a crucial transformation. (We already alluded to earlier in the book that Pester likes you to refactor your functions!) The direct invocation of the .Net method is replaced with a function call:

$result = Get-EnvironmentVariable -Variable $EnvVar

Here, Get-EnvironmentVariable acts as a protective shield. It

encapsulates the unpredictable .Net operation within a controlled

environment. By wrapping the .Net call in a PowerShell function (see

Listine achieve two critical goals:

1. Predictability for testing: The function can now

be mocked during tests. Instead of unpredictably

interacting with the OS, the function can return

predefined values, making tests reliable and

consistent.

149

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

2. Readability and maintainability: The script

becomes more readable. The intention

behind fetching the environment variable is

encapsulated in a function with a clear name

(Get-EnvironmentVariable), enhancing the script’s

readability and making maintenance easier.

This transformation not only resolves testing challenges but also

contributes to the script’s overall robustness and maintainability. By understanding and addressing the inherent issues via Listin, we pave the way for more predictable, manageable, and reliable PowerShell scripting.

To test the functionality now, we can craft Pester tests like Listing .

Listing 9-14. Testing the refactored function

Describe My-AmazingFunction {

it "Should return the variable if it exists" {

# Arrange

mock Get-EnvironmentVariable { "SampleValue"}

# Act

$expected = My-AmazingFunction -EnvVar "SampleValue"

# Assert

$expected | should -be "SampleValue"

}

it "Should return the False if the variable does

not exist" {

# Arrange

mock Get-EnvironmentVariable { }

# Act

150

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

$expected = My-AmazingFunction -EnvVar "SampleValue"

# Assert

$expected | should -beFalse

}

}

Listing

In the first It block, the mock Get-EnvironmentVariable { "SampleValue" }

statement is setting up a mock for the Get-EnvironmentVariable function.

This mock is simulating the behavior of the real Get-

EnvironmentVariable function and returning the string “SampleValue”.

When My-AmazingFunction -EnvVar "SampleValue" is called, it uses the mocked Get-EnvironmentVariable function, which always returns

“SampleValue”. The Assert section then checks if the returned value

matches the expected value “SampleValue”.

In the second It block, the mock Get-EnvironmentVariable { }

statement sets up a mock for the Get-EnvironmentVariable function that returns nothing, simulating the behavior when the environment variable does not exist.

When My-AmazingFunction -EnvVar "SampleValue" is called, it

also uses the mocked Get-EnvironmentVariable function, which now

returns nothing. The Assert section then checks if the returned value is False, indicating that the function correctly handles the scenario when the environment variable does not exist.

With these strategies up your sleeve, you’ll be taming .Net intricacies like a pro.

151

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Verifying Your Mocks: Ensuring Your Logic

Is Sound

So, you’ve mastered the art of mocking. Your functions are beautifully crafted, your tests are comprehensive, and everything seems to be working as expected. But how can you be absolutely certain that your mocks are doing what they’re supposed to do? This is where verification steps in.

Consider this scenario: you’ve set up a mock for Test-Path. You know

it should be called when your function runs, but how can you prove it?

Verification allows you to confirm that your logic is sound and that your function is interacting with the mock as intended.

Take, for instance, this sample function in Listing Get-Path.

Listing 9-15. The sample Get-Path function

function Get-Path {

param (

[parameter (Mandatory = $true,ValueFromPipeline

= $true)]

[string]$Path

)

process {

if (test-path $path) {

write-host "The path exists"

return $true

} else {

write-host "The path does not exist"

return $false

}

}

}

152

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

It takes a path, checks its validity, and writes a message accordingly.

Now, if you send a path like “C:\I\Exist”, you’d expect Test-Path to be called once. Similarly, if you send two paths down the pipeline, it should be called twice.

The Pester test script for validating this function could be structured as demonstrated in Listing h shows tests that validate Test-Path was called the correct number of times.

Listing 9-16. Testing the Get-Path function

Describe "Get-Path" {

BeforeAll {

Mock Write-Host

}

Context "When sending a path" {

It "Returns True if the path is valid" {

# Arrange

$path = "C:\I\Exist"

Mock test-path {$true}

# Act

$expected = Test-Path -Path $path

# Assert

$expected | Should -BeTrue

Should -invoke Test-path -times 1 -Exactly

}

It "Returns False if the path is not valid" {

# Arrange

$path = "C:\I\Do\Not\Exist"

Mock test-path {$false}

153

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

# Act

$expected = Test-Path -Path $path

# Assert

$expected | Should -BeFalse

Should -invoke Test-path -times 1 -Exactly

}

}

context "when sending via the pipeline" {

It "should call the mock the correct number

of times" {

# Arrange

Mock test-path {$true}

# Act

"c:\Exists", "c:\AlsoExists" | Get-Path

# Assert

Should -Invoke Test-path -times 2 -Exactly

}

}

}

This concept comes to life in your Pester tests. In Listin you create different contexts to test your function’s behavior. When testing a direct path, you assert that Test-Path is called once and only once: should -invoke Test-path -times 1 -Exactly

In the pipeline context, where two paths are sent, ("c:\path1","c:\ path2" | Get-Path), you adjust the -times parameter accordingly: should -invoke Test-path -times 2 -Exactly

154

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Here’s the key: using -times 2 -Exactly ensures that Test-Path is called precisely twice. This level of verification gives you confidence that your function is interacting with the mock exactly as planned. Without using –exactly, the test would pass if Test-Path was called at least two times.

Tip You also have the option to employ -Times 0 if you want to ensure with absolute certainty that a command is not called at all

or, alternatively, use the -not parameter to achieve the same result:

Should -not -Invoke Test-path

By verifying your mocks in this way, you’re not just writing tests; you’re ensuring the integrity of your functions. It’s a crucial step that adds a robust layer of reliability to your PowerShell scripts.

Understanding the Verification Line

Let’s wrap this section up by taking a little more time to make sure the verification line is fully understood before we continue the next part of our mocking journey.

This is the line that performs the verification magic:

should -invoke Test-Path -times 1 -Exactly

Here’s how it works:

– Should: We’ve covered this earlier in the book: This

keyword is fundamental in Pester. It’s like your testing

assistant, allowing you to set expectations about what

your code should do. It’s your way of saying, “Hey,

PowerShell, I expect this to happen.”

155

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

– Invoke test-path: Here, you’re specifying the

command or function that you’re keeping an eye on.

In our case, it’s Test-Path. You want to ensure that this

specific command is executed.

– Times 1: This part indicates how many times you

expect your command to be called. In the code snippet

provided earlier, Test-Path should be invoked once.

Think of it like counting instances. If your function

loops and calls Test-Path multiple times, this number

should match the total count.

– Exactly: This parameter is key. It emphasizes precision.

You’re not just saying “I want it to be called at least

once.” (which is what would happen if you omitted this

parameter), but you’re stating, “I want it to be called

exactly once, no more, no less.” It ensures the com-

mand is behaving as you’ve planned.

Imagine you’re baking cookies. You want to make sure the oven timer

rings exactly once when your cookies are done. If it rings too early, your cookies might be undercooked. If it rings too late, they could burn. Setting

-times 1 -Exactly is akin to ensuring that precise timing, guaranteeing your cookies (or in this case, your function) turn out just right.

Using a Parameter Filter

In this section, we explore the powerful feature of -ParameterFilter

within Pester’s Mock command, a tool designed to ensure your mocks

are invoked with precise parameter values. This parameter serves as a

gatekeeper, allowing the mocked behavior only if the incoming parameters meet the criteria defined in the filter. It’s crucial to note that if the filter conditions are not met, the original command will be invoked instead of the mock, potentially leading to unexpected behavior.

156

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Why Would You Use -ParameterFilter?

This feature shines when you need to test diverse code paths in your

functions. Imagine a scenario where a function behaves differently based on the input parameters. With -ParameterFilter, you can precisely mock the command and its varied outputs, allowing you to thoroughly test

different code paths.

How to Use -ParameterFilter

To leverage this filter, you simply define which parameters you want to ensure are passed, encapsulating them within a script block. If you have more than one parameter to consider, you can employ PowerShell’s

comparison operators like -eq. For instance, let’s take Get-Item as an example. It has a -Path property. To guarantee that the mock is invoked only when a specific path is used, you can employ the -ParameterFilter like this:

Mock Get-Item {} -ParameterFilter { $Path -eq "C:\MyPath" }

This construct allows you to precisely control when your mock

executes, ensuring that your tests comprehensively cover different code paths within your functions.

Let’s take an example to illustrate this concept. Consider a function

Get-User that returns different results for different usernames as shown in Listin

Listing 9-17. The sample Get-User function

Function Get-User {

param (

[string]$username

)

157

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

if ($username -eq 'admin') {

return 'Admin User'

} else {

return 'Regular User'

}

}

The accompanying tests shown in Listine mocks with parameter filters to control the function’s behavior based on input

parameters.

Listing 9-18. Using -ParameterFilter

Describe Get-User {

Context "When getting user information" {

beforeall {

mock Get-User {throw "Don't call Get-User

for real" }

}

it "Should return Admin User for 'admin'" {

# Arrange

Mock Get-User {

return 'Admin User'

} -ParameterFilter { $username -eq 'admin' }

# Act

$result = Get-User -username 'admin'

# Assert

$result | Should -Be 'Admin User'

}

it "Should return Regular User for other usernames" {

# Arrange

158

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Mock Get-User {

return 'Regular User'

} -ParameterFilter { $username -eq 'Joe' }

# Act

$result = Get-User -username 'Joe'

# Assert

$result | Should -Be 'Regular User'

}

}

}

In the provided example, the tests could pass without the

-ParameterFilter. However, the real power of -ParameterFilter

becomes evident in more complex scenarios where the function’s behavior hinges on specific parameter values. Here, the filter ensures that the mock is called only when the function is invoked with specific parameters,

allowing you to thoroughly test your code’s different pathways.

Gotta Catch ‘em All

It’s important to highlight the ‘Catch All’ mechanism for mocks,

implemented in the BeforeAll block. This catch-all prevents unexpected behaviors by intercepting function calls with parameters that don’t meet the criteria set by the -ParameterFilter.

Without this catch-all, if a function call doesn’t satisfy the filter

conditions, the mock won’t be invoked, and the real function will be

called instead. This safeguard ensures your tests remain robust even in complex scenarios, preventing inadvertent calls to the actual functions being mocked.

159

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

For instance, let’s consider a modification in our tests. If we alter the second It block to call the function: Get-User -username 'Joe' (as shown in Listing ), it doesn’t align with the parameter filter’s condition of $Username -eq 'Fred'. Consequently, the mock won’t be invoked in this

case. Instead, the real function will be called, a situation that might not align with your testing objectives.

This highlights the precision that -ParameterFilter offers in

selectively mocking specific function calls based on the specified

parameter conditions. The ‘Catch All’ mechanism in the BeforeAll

block becomes crucial here, ensuring that unexpected calls to the actual functions being mocked are prevented, thereby maintaining the integrity of your tests.

Listing 9-19. The real Get-User is called

Describe Get-User {

Context "When getting user information" {

beforeall {

mock Get-User {throw "Don't call Get-User

for real" }

}

it "Should return Admin User for 'admin'" {

# Arrange

Mock Get-User {

return 'Admin User'

} -ParameterFilter { $username -eq 'admin' }

# Act

$result = Get-User -username 'admin'

160

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

# Assert

$result | Should -Be 'Admin User'

}

it "Should return Regular User for other usernames" {

# Arrange

Mock Get-User {

return 'Regular User'

} -ParameterFilter { $username -eq 'Fred' }

# Act

$result = Get-User -username ' Joe'

# Assert

$result | Should -Be 'Regular User'

}

}

}

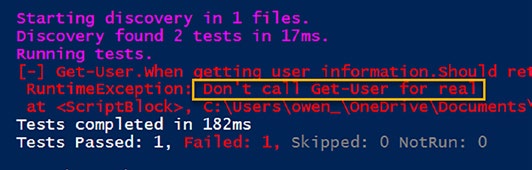

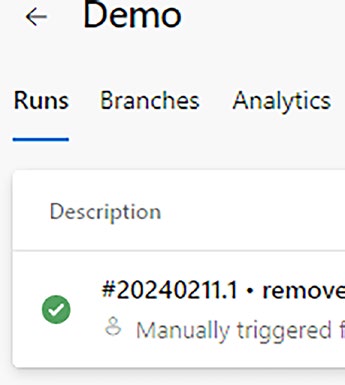

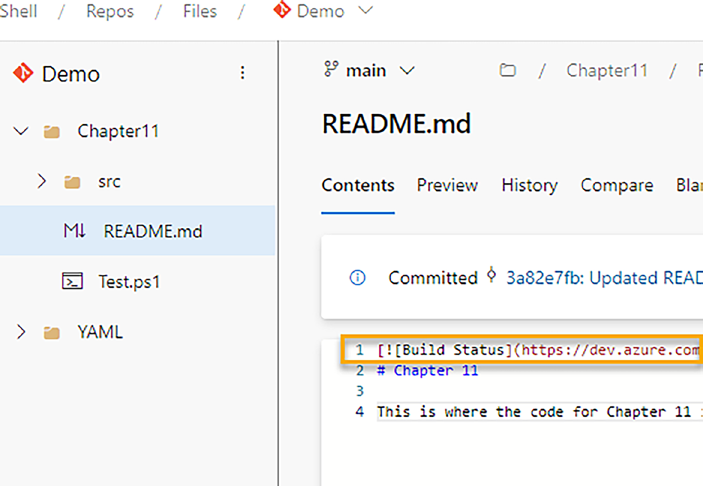

In Figurou can observe the ‘Catch All’ mechanism in action.

Here, the parameter filter set for the Get-User function is not met (as shown in the modified test: Listing causing the mock to be bypassed.

Instead, our safety-net is invoked, triggering the error message specified in the ‘Catch All’ block. This highlights the importance of the ‘Catch All’ in maintaining the expected behavior of your tests.

Figure 9-2. A close shave – saved by the catch all!

161

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Validating Output Messages Like a Boss

Using -ParameterFilter

When you are testing, ensuring the accuracy of output messages,

especially those generated by commands like Write-Host, Write-Output, or Write-Warning, is crucial.

This is where the powerful -ParameterFilter parameter in Pester’s

Mock command steps in. Consider the scenario of a function, Get-

Greeting, which employs Write-Host to display tailored messages based on input parameters. Listing trates this.

Listing 9-20. The sample function

Function Get-Greeting {

param (

[string]$Name

)

if ($Name -eq "Owen") {

Write-Host "Hello Owen, I hope you are having a

good day." -ForegroundColor Green

} else {

write-Warning "Oh, I see you are not Owen"

Write-Host "Hello $Name, how are you?" -ForegroundColor

Cyan

}

}

In the accompanying Pester test shown in Listing e utilize

-ParameterFilter to scrutinize the exact parameters passed to

Write-Host.

162

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Listing 9-21. The tests for Get-Greeting

Describe "Get-Greeting" {

Context "When the name is Owen" {

It "Should say hello to Owen" {

# Arrange

Mock Write-Host { }

$Name = 'Owen'

# Act

Get-Greeting -Name $name

# Assert

Should -Invoke Write-Host -ParameterFilter

{ $Object -eq "Hello Owen, I hope you are having a

good day." }

}

}

Context "When the name is not Owen" {

It "Should say hello to the name" {

# Arrange

Mock Write-Host { }

Mock Write-Warning { }

$Name = 'Bob'

# Act

Get-Greeting -Name $Name

# Assert

Should -Invoke Write-Host -ParameterFilter

{ $Object -eq "Hello $Name, how are you?"

-and $ForegroundColor -eq "Cyan" }

163

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

}

}

}

In the first context block, our focus is on verifying the correctness of the displayed message. In the second context, not only do we validate

the message, but we also ensure the accuracy of the foreground color

parameter, enhancing the precision of our tests.

This technique is particularly handy when dealing with scenarios

where refactoring the code is challenging due to various constraints as you can simply add a Write-Verbose or Write-Host message and check for

the correct message to verify correct code branching. Useful if you have nothing else to assert on.

Imagine your code as a vast, unpredictable sea, each function call

being like a message in a bottle. Sometimes, you need to ensure these

messages are delivered correctly and in the right bottle. Now, think of the

-ParameterFilter as a seasoned sailor’s compass. In the vast expanse of the code sea, it acts as your reliable navigation tool, helping you pinpoint not just the bottle but also the exact message inside it. Just as a sailor uses a compass to follow a specific route across stormy waters, -ParameterFilter allows you to precisely chart the path of your function calls amid the complexities of your code.

It’s not just about finding the bottles; it’s about ensuring each

message reaches its destination flawlessly. Like a skilled navigator using the compass to avoid treacherous rocks, you use -ParameterFilter to

steer clear of unexpected errors and ambiguities in your tests. In the sea of coding uncertainties, -ParameterFilter becomes your guiding

star, ensuring your messages are not lost at sea but reach their intended recipients with utmost accuracy and clarity.

164

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Note i realize the last few analogies are all over the place now, but i have to admit that this far into the book i’m fast running out of theater analogy ideas! From now on, it’s a free-for-all in the analogy department; it was good while it lasted!

Verifiable Mocks

In the dynamic world of PowerShell scripting, the reliability of your

functions is paramount. Verifiable Mocks, a powerful technique in

Pester, serve as vigilant sentinels, ensuring each function’s pivotal role in the script. By appending the -Verifiable badge, these mocks become

discerning critics, validating the script’s execution. Let’s delve into this technique, exploring how these mocks guarantee that every function takes its rightful place on the coding stage.

Ensuring the Right Performers Take the Stage

When coding, ensuring that each function plays its part correctly is

paramount. I’ve previously mentioned the use of should -invoke with

cmdlets like Write-Host and Write-Verbose, complemented by the

discerning -ParameterFilter. This technique becomes invaluable when

you need to guarantee that your code follows the expected logic path,

triggering the precise Write-Host or Write-Verbose messages.

A critical practice I employ involves orchestrating this validation

during the preparation phase of our “theatrical performance,” shifting the focus from the Assert section to the Arrange section of our test. Here, our mock functions transition from mere observers to active participants. We bestow upon them the responsibility of validation by appending the

-Verifiable parameter. This essential role, akin to a vigilant theater critic, ensures that specific functions are called precisely as anticipated.

165

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Consider the script demonstrated in Listing at stages the interaction between our code and two crucial performers, Write-Host and Write-Warning.

Listing 9-22. Invoke-Verifiable at large

Describe "Get-Greeting" {

Context "When the name is Owen" {

It "Should say hello to Owen" {

# Arrange

Mock Write-Host -ParameterFilter { $Object

-eq "Hello Owen, I hope you are having a good day."

} -Verifiable

# Act

Get-Greeting -Name "Owen"

# Assert

Should -InvokeVerifiable

}

}

Context "When the name is not Owen" {

It "Should say hello to the name" {

# Arrange

Mock Write-Warning { } -ParameterFilter

{ $Message -eq "Oh, I see you are not Owen" }

-Verifiable

Mock Write-Host { } -ParameterFilter

{ $Object -eq "Hello $Name, how are you?" -and

$ForegroundColor -eq "Cyan" } -Verifiable

$Name = 'Bob'

166

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

# Act

Get-Greeting -Name $Name

# Assert

Should -InvokeVerifiable

}

}

}

In the first act (context block) when the protagonist’s name is “Owen”, we scrutinize whether the correct message is displayed. Our mock function for Write-Host is marked as Verifiable by appending -Verifiable to the end of the mock, affirming its importance in our performance.

In the second act (context block), when our protagonist takes a

different identity, the same level of scrutiny is applied. Here, we validate not only the message but also the foreground color, demonstrating the

nuanced capabilities of -ParameterFilter in tandem with -Verifiable.

Additionally, Write-Warning is treated with the same -Verifiable

parameter.

The validation occurs seamlessly in the Assert section, where the

should -InvokeVerifiable scrutinizes the mock’s execution. It will check that every mock with -Verifiable tacked on to the end has been correctly called and, if not, will fail the test.

Moreover, the beauty of this approach lies in its efficiency. With just one line of code, you can verify all your mocks at once, in our example, all three, ensuring a comprehensive and robust evaluation of your script’s performance.

Verifiable Mocks also shine when we want to ensure the invocation of

functions that we don’t necessarily want to test. For instance, imagine a function responsible for sending emails or writing to a log file. We might not want to delve into their intricacies, but we certainly want to guarantee their execution. Enter the power of Verifiable Mocks. By appending the 167

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

-Verifiable switch to our mock commands, we command Pester to

scrutinize their performance. The subsequent should -InvokeVerifiable

in the Assert phase of the test then becomes our discerning audience,

ensuring that the functions took their rightful place on the stage.

Caution without a -ParameterFilter, should

-InvokeVerifiable will pass if the mock is called once or more

times. While this grants flexibility, it might compromise accuracy.

thus, striking a balance between flexibility and precision becomes a

vital consideration in your testing scripts.

In essence, Verifiable Mocks are the watchful guardians of your code,

ensuring that each function steps into the limelight as expected. By

bestowing upon them the -Verifiable badge, you guarantee not just code execution but an orchestrated performance that adheres to your script’s grand design. The theater of coding, with its splendid actors and vigilant critics, truly comes to life with the power of Verifiable Mocks.

Mocking Without Modules: Ensuring

Test Portability

Ensuring your tests run seamlessly across different environments is

crucial. Yet, when it comes to mocking functions or cmdlets that rely on specific modules or tools, guaranteeing this portability can be challenging.

Picture this: your tests run smoothly on your computer, where all the

necessary modules are installed, but the moment someone else attempts

to run them, or they are integrated into an automated CI/CD pipeline,

disaster strikes – the tests fail.

168

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Pester, in its wisdom, creates mock versions of functions or cmdlets,

expecting them to be present on the testing machine. This becomes

problematic when the tests are executed in environments lacking the

required modules. So how do you ensure your tests don’t fail in these

scenarios? The solution lies in creating a simplified version of the required function or cmdlet directly within your Pester test.

Consider this scenario: you’re testing a function called Get-

ADUserDisabledState. This function interacts with Get-ADUser, a cmdlet from the Active Directory module. Listin shows this function.

Listing 9-23. The sample Get-ADUserDisabledState function Function Get-ADUserDisabledState {

param (

[bool]$State = $false

)

$users = @(Get-Aduser -Filter {Enabled -eq $State}

-SearchBase = 'OU=Users,OU=MyCompany,DC=OH,DC-Local')

if ($state -eq $false) {

Write-Host "There are $($users.Count) disabled

user accounts:"

$users.name

} else {

Write-Host "There are $($users.Count) enabled

user accounts:"

$users.name

}

}

To guarantee test portability, you recreate Get-ADUser within your test environment.

169

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

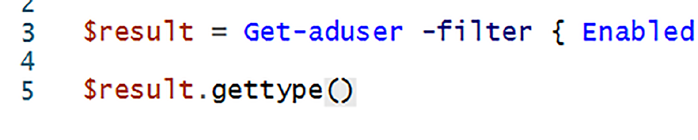

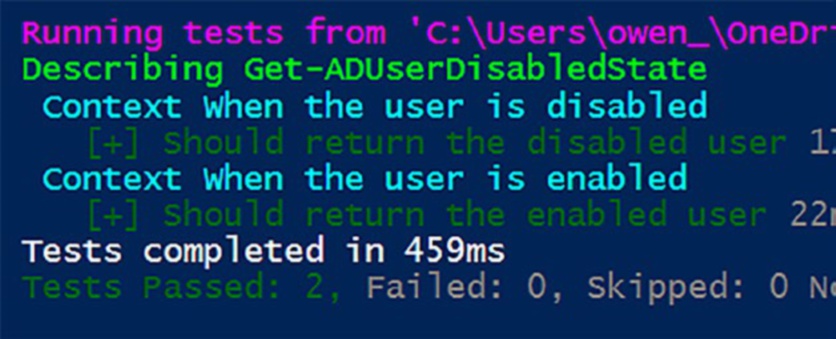

Before writing the test, I used GetType against the results of Get-ADUser to see what type of object was used to return the data as shown in Figurigure .

Figure 9-3. Using GetType to determine the returned object

Figure 9-4. It’s a PSCustomObject!

So I’ll mock with a PSCustom object too. Listin shows what the tests looks like initially.

Listing 9-24. Well, it worked on my computer!

Describe "Get-ADUserDisabledState" {

Context "When the user is disabled" {

It "Should return the disabled user" {

# Arrange

mock Get-ADUser {

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = "Test User1"

170

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Enabled = $false

}

}

# Act

$expected = Get-ADUserDisabledState -State $false

# Assert

$expected | Should -Be "Test User1"

}

}

Context "When the user is enabled" {

It "Should return the enabled user" {

# Arrange

mock Get-ADUser {

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = "Test User2"

Enabled = $True

}

}

# Act

$expected = Get-ADUserDisabledState -State $true

#Assert

$expected | Should -Be "Test User2"

}

}

}

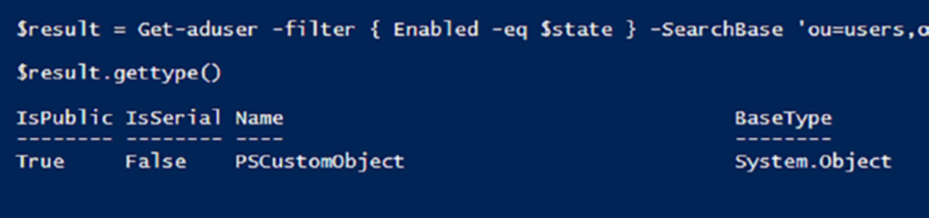

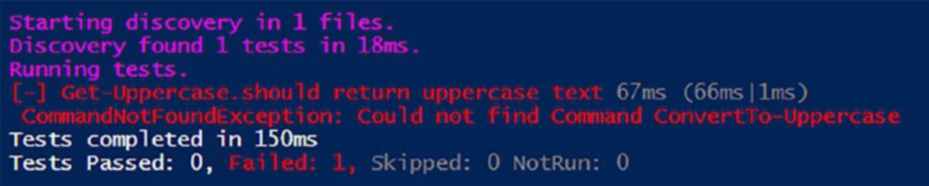

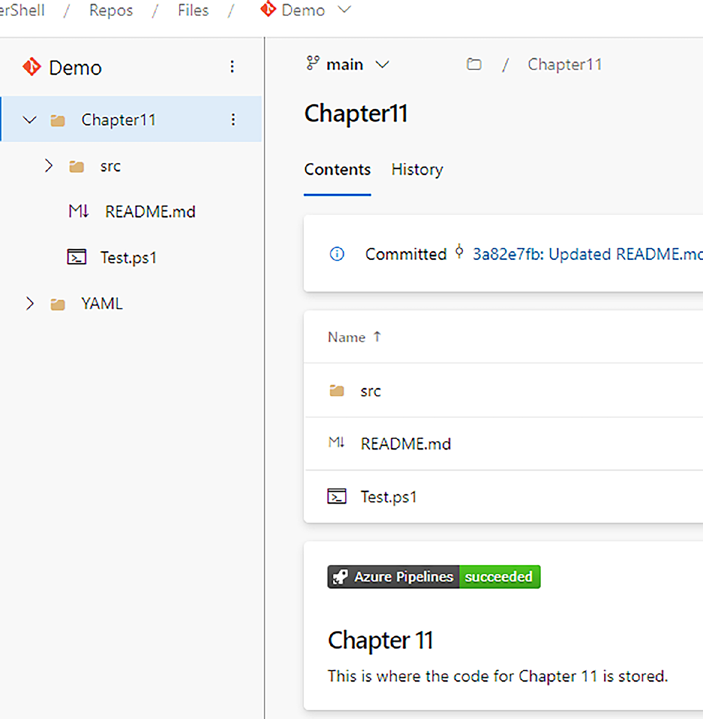

If I run the test on a system that does not have access to Get-ADUser, the test fails (Figure ). And tells you in no uncertain terms, “Could not find Command Get-ADuser”

171

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Figure 9-5. The test failed because the AD cmdlets were not installed on this computer

The solution is to define a blank function of the same name within

your test, as demonstrated by Listing ithin the BeforeAll script block.

Listing 9-25. It’s an easy solution, simply define a blank function Describe "Get-ADUserDisabledState" {

beforeAll {

Function Get-ADUser {}

Mock Write-Host {}

}

Context "When the user is disabled" {

It "Should return the disabled user" {

# Arrange

mock Get-ADUser {

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = "Test User1"

Enabled = $false

}

}

# Act

$expected = Get-ADUserDisabledState -State $false

172

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

# Assert

$expected | Should -Be "Test User1"

}

}

Context "When the user is enabled" {

It "Should return the enabled user" {

# Arrange

mock Get-ADUser {

[PSCustomObject]@{

Name = "Test User2"

Enabled = $True

}

}

# Act

$expected = Get-ADUserDisabledState -State $true

#Assert

$expected | Should -Be "Test User2"

}

}

}

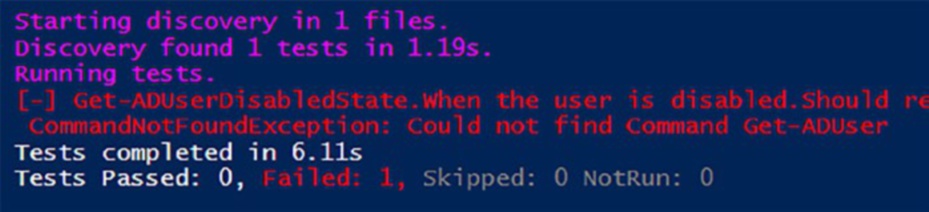

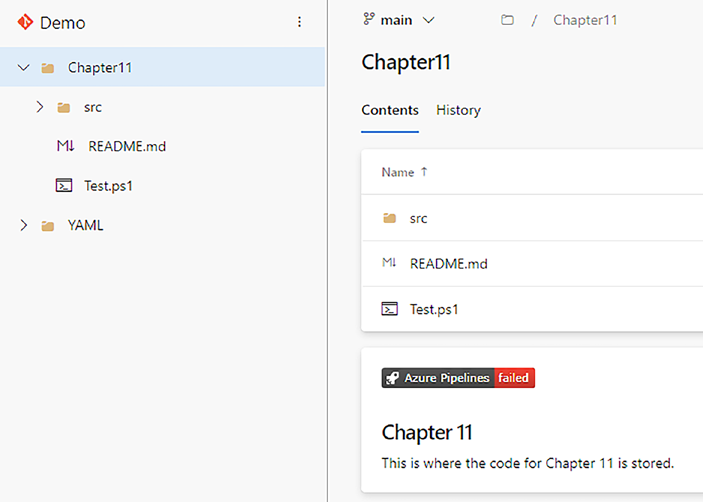

Figurw shows the results of the “dummy” function: the test suite passes with flying colors.

173

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Figure 9-6. The test passes even though Get-ADUser is not installed on the computer

By simulating the necessary functions directly within your test, you

ensure that the tests remain robust and functional, regardless of the

absence of specific modules in different environments. This technique

ensures your tests are not just reliable on your machine but are also ready to perform flawlessly on any stage, ensuring the integrity of your code across diverse settings.

Mocking with Modules: Navigating

Module Scopes

Modules, the building blocks of PowerShell’s modular architecture, often contain a mix of public and private functions. Testing these modules,

especially the private functions, presents a unique challenge. Consider a scenario where a module defines a private function internally used

by a public function. How do you mock this private function for testing purposes?

In our example module, seen in Listing ublic function Get-UpperCase internally calls the private function ConvertTo-UpperCase to perform its task.

174

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Listing 9-26. Our sample module that calls a private function Function ConvertTo-UpperCase {

param (

[string]$text

)

return $text.ToUpper()

}

Function Get-UpperCase {

param (

[string]$Text

)

return ConvertTo-UpperCase -text $Text

}

Export-ModuleMember -Function Get-UpperCase

When attempting to mock the private function without specifying its

module context as shown in Listing , your test might fail to locate the function, leading to unexpected results.

Listing 9-27. The test fails to locate the private function BeforeAll {

Import-Module "$PSScriptRoot\Mock_module01.psm1"

-Force -PassThru

}

Describe "Get-Uppercase" {

It "should return uppercase text" {

mock ConvertTo-Uppercase -MockWith {"HELLO"}

$expected = Get-UpperCase -Text "hello"

175

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

$expected | should -be "HELLO"

}

}

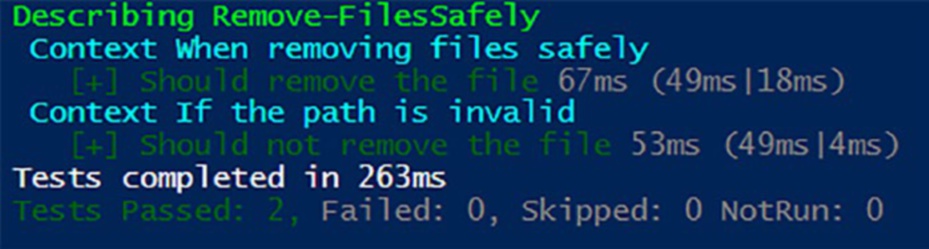

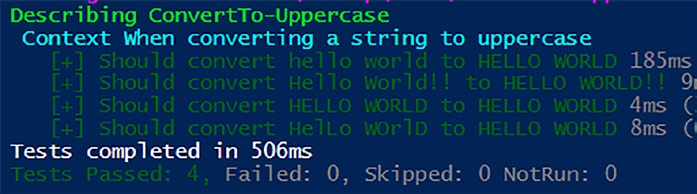

Figurws the results of executing Listing

Figure 9-7. The test fails – it could not find the private function

“ConvertTo-UpperCase”

Two common approaches to mitigate this is to use the -ModuleName

parameter or encapsulate the test within an InModuleScope script block.

Using the -ModuleName Parameter

By specifying the module name when mocking a private function, you

explicitly indicate the module context for the mock. In the test scenario, this approach ensures the mock operates within the correct scope,

enabling the test to locate the private function and perform as expected.

Not only does this method provide speed advantages, but it also enhances code clarity. You clearly define the module context, making your tests more understandable for both yourself and other developers.

You are only required to add -ModuleName to any Mock or Should

-Invoke commands within your test suite as demonstrated by Listing

Listing 9-28. Using -ModuleName for speed and clarity

BeforeAll {

Import-Module "$PSScriptRoot\<moduleName>.psm1"

176

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

-Force -PassThru

}

Describe "Get-Uppercase" {

It "should return uppercase text" {

# Arrange

mock ConvertTo-Uppercase -MockWith {"HELLO"}

-ModuleName moduleName

# Act

$expected = Get-UpperCase -Text "hello"

# Assert

$expected | should -be "HELLO"

should -invoke ConvertTo-UpperCase -times 1

-exactly -ModuleName moduleName

}

}

Note this will only allow you to mock private functions that are called by your public functions. i

(Get-Uppercase) calls the private function (ConvertTo-Uppercase).

if you wish to write a unit test for a private function directly, you will need to use inModuleScope.

Using InModuleScope Script Block

Alternatively, you can encapsulate your tests within an InModuleScope script block. This approach ensures everything inside the block runs

within the module scope. However, be cautious, as this method makes

177

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

both public and private functions in the module available to your tests, potentially leading to undesired consequences. Listin demonstrates this approach.

Listing 9-29. Sometimes you have no option but to use

InModuleScope

BeforeAll {

Import-Module "$PSScriptRoot\<moduleName>.psm1"

-Force -PassThru

}

Describe "Get-Uppercase" {

It "should return uppercase text" {

InModuleScope 'moduleName' {

# Arrange

mock ConvertTo-UpperCase -MockWith {"HELLO"}

# Act

$expected = Get-UpperCase -Text "hello"

# Assert

$expected | should -be "HELLO"

should -invoke ConvertTo-UpperCase -times

1 -exactly

}

}

}

To follow best practice, you should avoid wrapping InModuleScope

around your Describe or It blocks – sure, it can be done, but you will end up slowing down the Discovery Phase and won’t ensure that your

functions are properly tested.

178

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

Note using

InModuleScope has a significant benefit: it provides

access to all functions within the module, both public and private.

this means you can call a private function in your test script, rather than mock it, even if it hasn’t been exported by the module. it’s

also handy if you need to write a unit test for a private function in

the module.

While both methods achieve the goal, using the -ModuleName

parameter is considered best practice due to its speed, specificity, and clarity advantages. This explicit indication of the module context makes your tests robust, efficient, and easy to comprehend, ensuring the smooth navigation of module scopes during testing.

Summary

While this chapter may have tested your persistence, the invaluable skills you’ve gained are well worth the effort. You’ve embarked on a journey

into the art of mocking in PowerShell, a fundamental practice for powerful and effective testing. By exploring the sample code, delving into diverse examples, and rereading key concepts, you’ve equipped yourself with the knowledge to transform how you test your scripts.

Through various examples and scenarios, you’ve explored the nuances

of mocking, from simple function mocks to more complex interactions

involving parameters and module scopes.

You’ve discovered the power of -ParameterFilter in honing

your mocks to specific conditions, ensuring precise testing of diverse code paths. You’ve explored the concept of Verifiable Mocks, vigilant

gatekeepers that validate function invocations, bolstering the integrity of your tests. Moreover, you’ve learned the art of mocking private functions within modules, crucial for testing encapsulated code.

179

Chapter 9 MoCking Your WaY to SuCCeSS

By mastering these techniques, you’ve gained the power to

comprehensively validate your PowerShell scripts. Whether it’s simulating specific scenarios, validating complex interactions, or testing encapsulated code, you now possess the tools to elevate your testing game.

Beyond This Chapter

Remember, effective testing is not just about verifying your code;

it’s about ensuring its robustness under diverse conditions. Mocking

empowers you to create controlled environments, simulate various

situations, and assess your scripts’ behavior with confidence.

Your Journey Continues

Now that you’ve mastered the art of mocking, are you curious about how much of your code you’re actually testing? Dive into the captivating world of code coverage in the next chapter, where we’ll unveil techniques to measure and maximize the effectiveness of your test suite. Get ready to unveil hidden corners of your code and ensure its robustness like never before!

180

CHAPTER 10

Unveiling the Secrets

of Code Coverage

By now, you’ve mastered the art of crafting powerful Pester tests. But have you ever wondered: are you testing all the corners of your code? This is where the intriguing concept of code coverage comes into play.

Imagine having a map that visualizes which areas of your code

have been thoroughly tested and identifies any hidden pathways left

unexplored. Code coverage gives you just that! In this chapter, you’ll embark on a journey to

Demystify code coverage: Understand what it is,

why it matters, and the different metrics used to

measure it.

Generating insights: Discover how to interpret

coverage reports, identify untested areas, and

prioritize future testing efforts.

Optimizing tests and code: Utilize insights from

coverage data to refine your testing strategy,

write targeted tests, and ensure your code is well

protected from unseen issues.

By the end of this chapter, you’ll understand how to maximize your

testing investment and achieve peace of mind knowing your code is robust and ready for any challenge.

© Owen Heaume 2024

181

O. Heaume, Getting Started with Pester 5

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Demystifying Code Coverage: Unveiling

the Map of Your Code’s Tested Terrain

Imagine building a magnificent castle, brick by painstaking brick. But how can you be sure every brick is strong and contributes to its overall stability?

Code coverage serves as the architect’s blueprint, highlighting which areas of your code have been tested and ensuring no hidden weaknesses remain undetected.

In essence, code coverage measures the percentage of your code that

is executed during testing. It’s like having a map that lights up specific regions when you walk over them, revealing how thoroughly you’ve

explored your code’s landscape. But why is this so important?

Well, untested code is like an unexplored path in the wilderness,

potentially harboring unexpected pitfalls. High code coverage minimizes the chance of hidden bugs lurking in the shadows, protecting your scripts from unexpected behavior and ensuring reliability. Imagine blindly firing arrows into the darkness hoping to hit the target. Code coverage reports act as spotlights, illuminating areas that haven’t been tested, allowing you to prioritize and streamline your testing efforts for maximum impact.

Knowing your code is well tested fosters confidence and reduces anxiety.

With high coverage, you can sleep soundly knowing you’ve covered all the bases and your scripts are prepared to handle real-world situations.

Metrics: Unveiling the Degrees of Coverage

Just like maps use different symbols to represent terrain, code coverage utilizes various metrics to gauge your testing comprehensiveness. For

instance:

Statement coverage: Tracks the percentage of

individual code statements executed during tests.

182

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Branch coverage: Measures how well different

decision points (e.g., if-else statements) are

exercised by tests.

Function coverage: Ensures each function or

method within your code is called at least once

during testing.

Remember, a single metric doesn’t paint the whole picture. A healthy

mix of metrics helps you analyze different aspects of your code’s coverage and create a more comprehensive understanding.

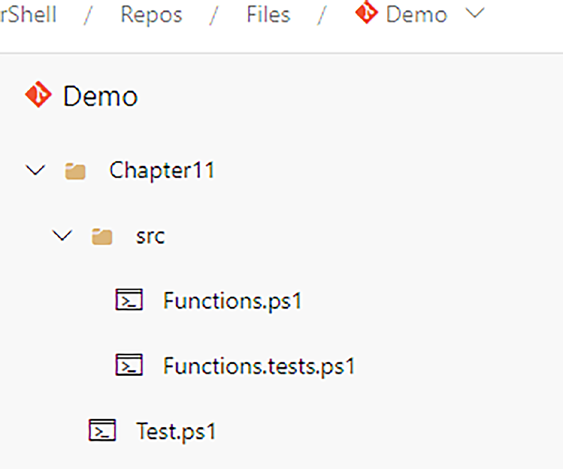

Sample Functions and Tests

Before delving into code coverage, let’s visit our sample functions:

Compliment-Yourself and Compliment-Owen shown in Listing .

Listing 10-1. Our sample functions are contained in our Functions.ps1 file

function Compliment-Yourself {

$randomNumber = Get-Random -Minimum 1 -Maximum 3

if ($randomNumber -eq 1) {

return 'You are doing great!'

} else {

return 'Keep up the good work!'

}

}

Function Compliment-Owen {

$randomNumber = Get-Random -Minimum 1 -Maximum 3

183

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

if ($randomNumber -eq 1) {

return 'Well done Owen, you are doing great!'

} elseif ($randomNumber -eq 2) {

return 'Hey Owen! Keep up the good work!'

} else {

return 'This is a great chapter!'

}

}

These functions are accompanied by the Pester tests demonstrated by

Listin

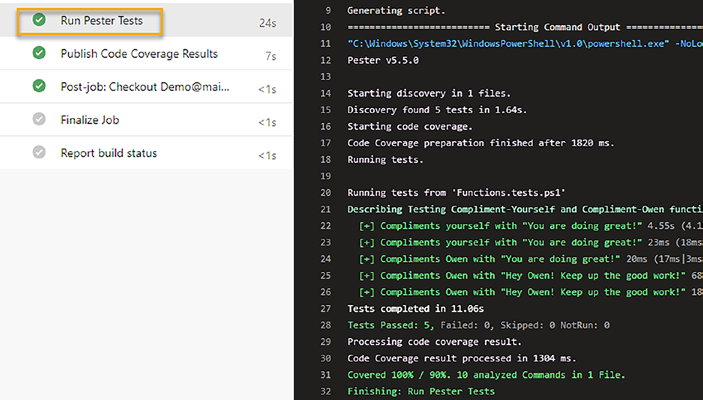

Listing 10-2. The pester tests: our Functions.tests.ps1 file beforeall {

. "$psscriptroot\Functions.ps1"

}

Describe 'Testing Compliment-Yourself and Compliment-Owen' {

It 'Compliments yourself with "You are doing great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Yourself

$result | Should -Be 'You are doing great!'

}

It 'Compliments Owen with " Well done Owen,

You are doing great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Owen

184

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

$result | Should -Be 'Well done Owen, you

are doing great!'

}

}

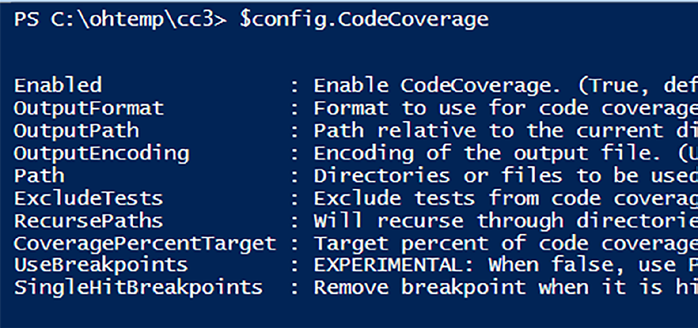

Now, let’s see what code coverage can do for us in helping to identify areas for testing improvement by creating our configuration file.

Pester Code Coverage Configuration

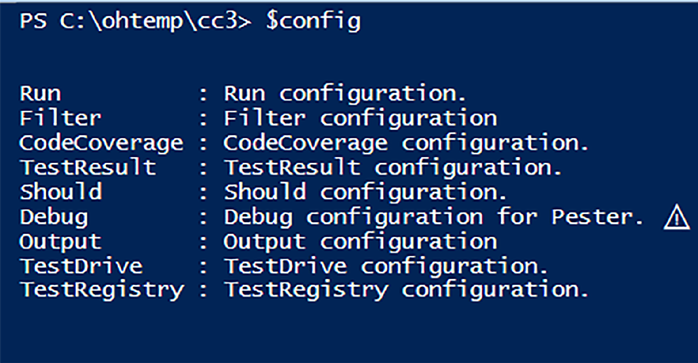

Configuring a Pester configuration file is our first step. In Listine leverage New-PesterConfiguration to specify the path to our test file and activate code coverage. We’ve saved this separate file as Test.ps1.

Listing 10-3. Our Pester Code Coverage Configuration Item saved as Test.ps1

$config = New-PesterConfiguration

$config.Run.Path = ".\src\Functions.tests.ps1"

$config.CodeCoverage.Enabled = $true

Invoke-Pester -Configuration $config

Let’s take a moment and walk through step-by-step what we’ve

just done.

Step 1: Utilizing New-PesterConfiguration

The core of your configuration endeavors lies in the New-PesterConfiguration cmdlet. This command sets the stage for defining how Pester should conduct its tests, including the critical aspect of code coverage.

# Creating a new Pester configuration object

$config = New-PesterConfiguration

185

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

This command initializes a configuration object, a bit like creating a blueprint that informs Pester exactly what to do. Think of it as the master plan for orchestrating your tests, ensuring they align with your specific needs and goals.

Step 2: Setting the Test File Path

With the configuration object in hand, the next step is to specify the path to your test file. This ensures Pester knows exactly where to find and execute the tests. The Run.Path property serves this purpose.

# Setting the path to the test file

$config.Run.Path = ".\src\Functions.tests.ps1"

By defining the test file path, you’re providing Pester with a roadmap to navigate through your tests and execute them systematically.

Step 3: Activating Code Coverage

Now comes the pivotal moment – activating code coverage.

# Activating code coverage

$config.CodeCoverage.Enabled = $true

When you enable CodeCoverage.Enabled, you’re telling Pester to

unlock a whole new level of insight into your code – it’s like giving it a map to explore every line that your tests touch.

Step 4: Invoking Pester with the Configuration

Finally, the Invoke-Pester cmdlet, coupled with your configuration

object, is the catalyst for initiating the testing process.

# Invoking Pester with the configuration

Invoke-Pester -Configuration $config

186

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

This command kicks off the testing journey, leveraging the detailed

configuration you’ve constructed. Pester now traverses through your tests, executes them, and, thanks to code coverage activation, provides insights into how thoroughly your code is being tested.

Running the Configuration

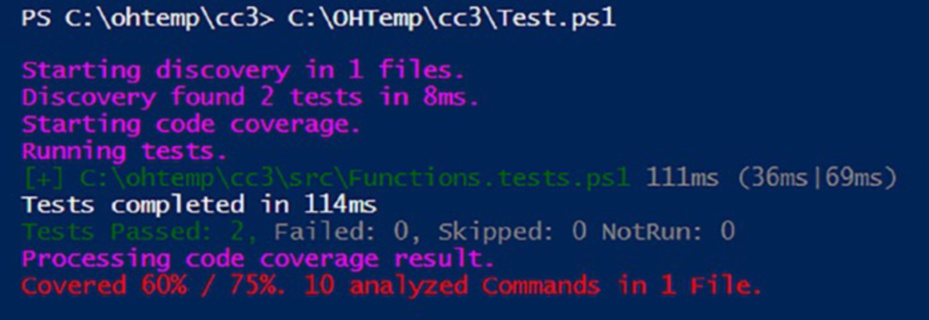

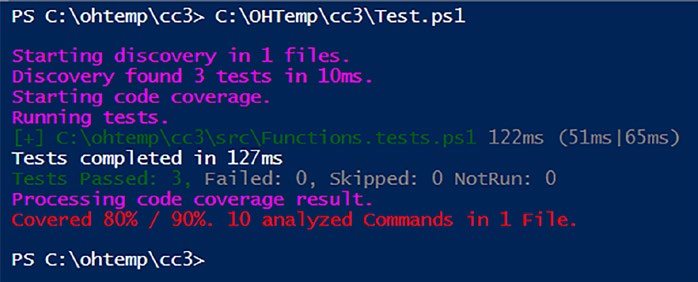

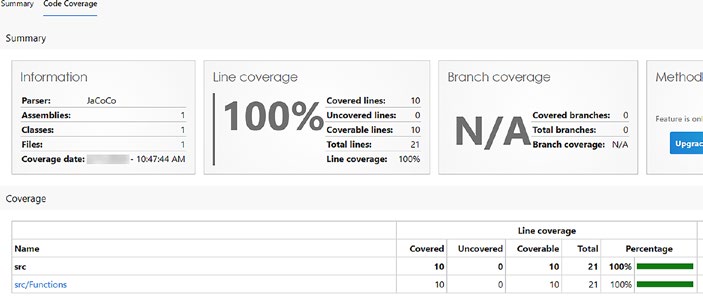

Now we have our configuration file saved as Test.ps1, we can run it. Doing so will execute our tests as well as present us with some code coverage metrics as shown in Figur.

Figure 10-1. Code coverage metrics

Breaking Down the Metrics

By default, the code coverage configuration employs a 75% threshold for the amount of code that needs to be covered for a successful pass. In the current report, we’ve attained a coverage rate of 60% against this 75%

benchmark. Clearly, there is room for enhancement in our testing efforts!

On closer inspection of the Functions.tests.ps1 file we can see we inadvertently forgot to test for this particular section of code in our Compliment-Owen function:

...elseif ($randomNumber -eq 2) {

return 'Hey Owen! Keep up the good work!' ...

187

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Let’s fix this and add a test for it. Listing ws the revised

.tests file.

Listing 10-4. Adding a new test for better code coverage beforeall {

. "$psscriptroot\Functions.ps1"

}

Describe 'Testing Compliment-Yourself and Compliment-Owen' {

It 'Compliments yourself with "You are doing great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Yourself

$result | Should -Be 'You are doing great!'

}

It 'Compliments Owen with " Well done Owen, You are doing

great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Owen

$result | Should -Be 'Well done Owen, you are

doing great!'

}

It 'Compliments Owen with "Hey Owen! Keep up the

good work!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 2 }

188

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

$result = Compliment-Owen

$result | Should -Be 'Hey Owen! Keep up the

good work!'

}

}

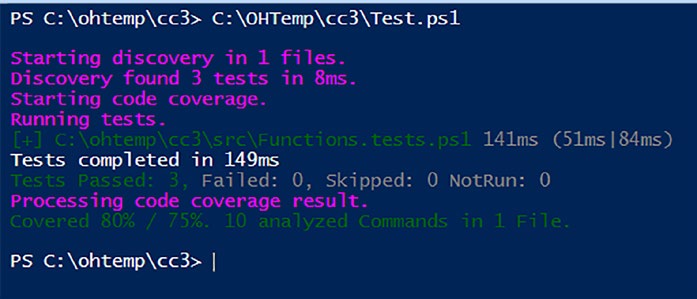

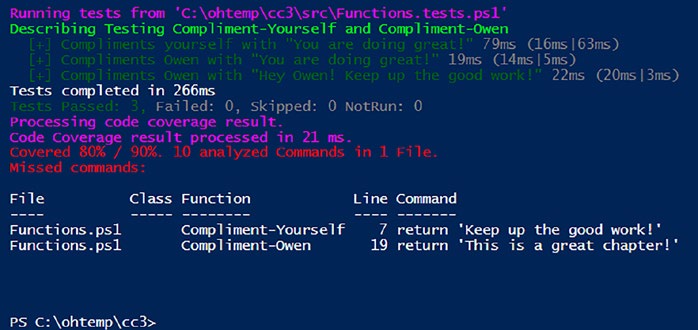

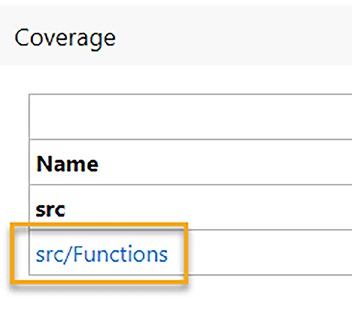

Executing our Pester configuration file for code coverage now reveals

the ensuing metrics, as depicted in Figure .

Figure 10-2. Success! We have green lights!

Fantastic news! We’ve reached an impressive 80% of our initial

75% target. However, aiming higher, I prefer a 90% code coverage. To

accomplish this, we can elevate our aspirations by including the following line in our Pester Configuration file:

$config.CodeCoverage.CoveragePercentTarget = 90

With this addition, we are now striving to achieve a commendable 90%

code coverage as demonstrated in Listing

189

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Listing 10-5. Setting the target code coverage to 90%

$config = New-PesterConfiguration

$config.Run.Path = ".\src\Functions.tests.ps1"

$config.CodeCoverage.Enabled = $true

$config.CodeCoverage.CoveragePercentTarget = 90

Invoke-Pester -Configuration $config

If we now run the code coverage configuration file again, we see the

following metrics as shown in Figur.

Figure 10-3. We are now 10% shy of our target

With the current coverage standing at 80%, there’s a remaining 10% to

fulfill our target. To pinpoint precisely what areas we’ve missed in our tests, let’s introduce an additional line to our Pester configuration file:

$config.Output.Verbosity = "Detailed"

This adjustment enhances the verbosity of our output, providing

detailed insights into the areas that require further testing to meet our ambitious 90% code coverage target. Listing shows the configuration file with our new addition.

190

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Listing 10-6. The new Pester configuration file

$config = New-PesterConfiguration

$config.Run.Path = ".\src\Functions.tests.ps1"

$config.CodeCoverage.Enabled = $true

$config.CodeCoverage.CoveragePercentTarget = 90

$config.Output.Verbosity = "Detailed"

Invoke-Pester -Configuration $config

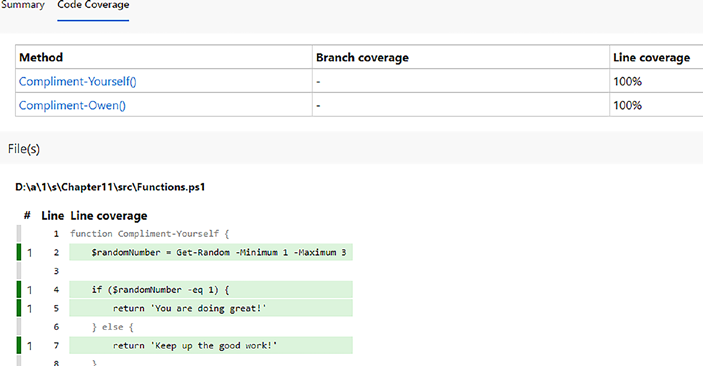

Running our configuration file now gives us the following metrics as

shown in Figure

Figure 10-4. Detailed metrics

Indeed, the decision to elevate the verbosity level to “Detailed”

proves to be an excellent move. This adjustment not only provides a more intricate view of our test results but also illuminates exactly what has been overlooked in our tests. The metrics now clearly indicate that line 7 in the Compliment-Yourself function and line 19 in the Compliment-Owen function were not executed under any of the tests within our test suite.

191

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

With this detailed information, we can discern which functions, the

specific line numbers, and precisely what needs to be tested to address the gaps in our coverage.

Listinoudly showcases our refined .tests file, adorned with the latest additions to our test suite. These new tests have been carefully incorporated to address the areas we previously missed, as highlighted by the detailed insights gleaned from our code coverage metrics.

Listing 10-7. Two new tests have been added, one for each function as identified by the code coverage metrics

beforeall {

. "$psscriptroot\Functions.ps1"

}

Describe 'Testing Compliment-Yourself and

Compliment-Owen function' {

It 'Compliments yourself with "You are doing great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Yourself

$result | Should -Be 'You are doing great!'

}

It 'Compliments yourself with "Keep up the good work!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 2 }

$result = Compliment-Yourself

$result | Should -Be 'Keep up the good work!'

}

192

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

It 'Compliments Owen with "Well done Owen,

you are doing great!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 1 }

$result = Compliment-Owen

$result | Should -Be 'Well done Owen,

you are doing great!'

}

It 'Compliments Owen with "Hey Owen!

Keep up the good work!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 2 }

$result = Compliment-Owen

$result | Should -Be 'Hey Owen! Keep up

the good work!'

}

It 'Compliments Owen with "This is a great chapter!"' {

# Mocking the random number to ensure the

specific branch is tested

Mock Get-Random { 3 }

$result = Compliment-Owen

$result | Should -Be 'This is a great chapter!'

}

}

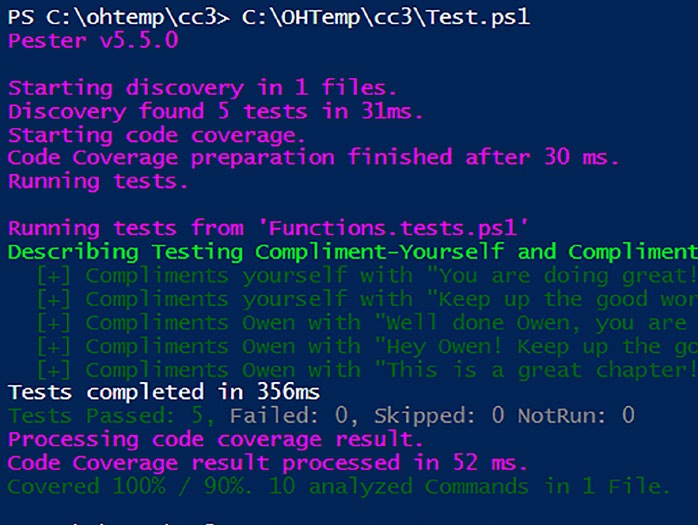

Each line in this revised file is a testament to our commitment to

thorough testing.

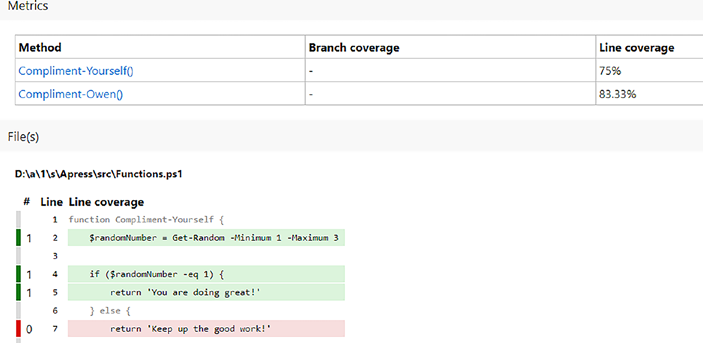

If we run the code coverage configuration once more, we are presented

with the metrics as shown in Figur

193

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Figure 10-5. We have 100% code coverage!

Triumphant news! We’ve achieved the pinnacle of success – a perfect

100%! This stellar outcome surpasses our initial target of 90%, signifying that every nook and cranny of our code has been thoroughly covered by

our tests.

Best Practices for Code Coverage Targets

There isn’t a universally defined “best practice” percentage for code

coverage targets in Pester or any other testing framework. The appropriate target for code coverage can vary based on the specific needs and goals of a project, team, or organization.

194

Chapter 10 Unveiling the SeCretS of Code Coverage

Some projects may aim for a high code coverage target, such as

90% or more, to ensure a comprehensive set of tests covers most of the codebase. This can be particularly important in safety-critical systems or environments with stringent quality assurance requirements.

On the other hand, some projects may find a lower code coverage