Упражнения

1. Выберите правильный вариант:

1. There is a law in Germany that nobody may sleep on the ground.

2. There is a law in Germany that nobody may ask for money.

3. There is a law in Germany that nobody may scatter paper about the street.

4. There is a law in Germany that nobody may dance outside the house.

ОТВЕТ: There is a law in Germany that nobody may scatter paper about the street.

2. Where was an English military friend of mine?

1. in Dresden

2. in Berlin

3. in Stuttgart

4. in Paris

ОТВЕТ: in Dresden

3. Who is a Cook’s agent?

1. the policeman

2. the travel agent

3. the man who can cook well

4. the military man

ОТВЕТ: the travel agent

4. Why did an American lady disregard rules?

1. Because she did not understand the language.

2. Because she was very proud.

3. Because she did not know what to do.

4. Because she was young.

ОТВЕТ: Because she was very proud.

5. What is a Schauspielhaus?

1. a French cabaret

2. a Russian restaurant

3. an English circus

4. a German theatre

ОТВЕТ: a German theatre

6. Where is Brussels situated?

1. in Belgium

2. in Holland

3. in France

4. in Italy

ОТВЕТ: in Belgium

7. Выберите правильный вариант:

1. The policeman examined him for some hours.

2. The policeman examined him thirty minutes.

3. The policeman examined him for an hour.

4. The policeman examined him for about a quarter of an hour.

ОТВЕТ: The policeman examined him for about a quarter of an hour.

8. Why did the conductor want to know about the lady?

1. Because he wanted to see her ticket.

2. Because he thought my friend was a liar.

3. Because he had never seen ladies.

4. Because he wanted to sell her a ticket.

ОТВЕТ: Because he thought my friend was a liar.

9. What king was nearly drowned?

1. an English king

2. a Russian king

3. a Spanish king

4. a French king

ОТВЕТ: a Spanish king

10. Выберите нужный глагол:

The spectators must _______ off their hats.

1. take

2. make

3. bring

4. lie

ОТВЕТ: The spectators must take off their hats.

11. Выберите нужные глаголы:

When the foreign dog ________ a cat in a hurry, it ________ aside.

1. see, stand

2. saw, stand

3. saw, stands

4. sees, stands

ОТВЕТ: When the foreign dog sees a cat in a hurry, it stands aside.

12. Выберите нужный предлог:

An English owner of that fox-terrier normally will jump __________ the nearest tram.

1. upon

2. in

3. at

4. behind

ОТВЕТ: An English owner of that fox-terrier normally will jump upon the nearest tram.

13. Ответьте на вопросы:

1. Who are foreigners?

2. Are there many foreigners in your country?

3. What have you learned about them?

4. What do you like and what don’t you like in foreigners?

5. What would you do if you were the foreigner?

6. What is the end of the story?

7. How can you explain the title of the story?

8. Retell the story.

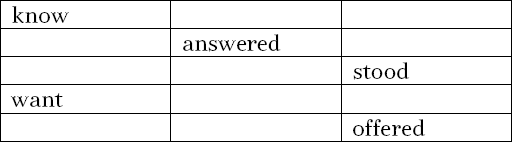

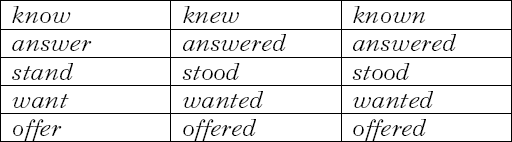

14. Заполните таблицу:

ОТВЕТ:

The Man Who Would Manage

They say – and I can believe it – that at nineteen months of age he wept because his grandmother did not allow him to feed her with a spoon, and that at three and a half he was trying to teach a frog to swim.

Two years later he nearly injured his left eye, when he was showing the cat how to carry kittens safely, and about the same period he was dangerously hurt by a bee when he was trying to replace it from one flower to another, where, as he thought, there was more honey.

His desire was always to help others. He could spend whole mornings explaining to elderly hens how to hatch eggs, and he cancelled his afternoon’s walk to sit at home and crack nuts for his pet squirrel. Before he was seven he was arguing with his mother upon the management of children, and reprove his father for incorrect education.

As a child he liked to mind other children. It was not important to him whether the other children were older than himself or younger, stronger or weaker, whenever and wherever he found them he began to mind them. Once, during a school treat, the teacher heard piteous cries from a distant part of the wood. The teacher discovered him upon the ground, his cousin, a boy twice his own weight, was sitting upon him and steadily whacking him. The teacher rescued him and asked:

“Why don’t you play with the little boys? What are you doing with him?”

“Please, sir,” was the answer, “I was minding him.”

He was a good-natured lad, and at school he was always allowing the whole class to copy from his paper. Unfortunately, his answers were awfully wrong, and the result to his followers was bad. So they were waiting for him outside later and punching him.

All his energies went to the instruction of others. He took young boys to his house taught them to box.

“Now, try and hit me on the nose,” he offered. “Don’t be afraid. Hit as hard as you can.”

And they did it. When he had recovered from his surprise, and a little lessened the bleeding, he explained to them how they had done it all wrong.

Twice at golf he lamed himself for over a week, when he was showing how to play. After that he had a long argument with the umpire.

During a stormy Channel passage, he rushed excitedly upon the bridge in order to inform the captain that he had “just seen a light about two miles away to the left”; and when he is on the top of an omnibus he generally sits beside the driver, and shows him how to drive.

It was upon an omnibus where I met him. I was sitting behind two ladies when the conductor came up to collect fares. One of them gave him a sixpence and told him to take to Piccadilly Circus, which was twopence.

“No,” said the other lady to her friend, and gave the man a shilling, “I owe you sixpence, you give me fourpence and I’ll pay for the two.”

The conductor took the shilling, gave two twopenny tickets, and then began to think about the change.

“That’s right,” said the lady who had spoken last, “give my friend fourpence.”

The conductor did so.

“Now you give that fourpence to me.”

The friend handed it to her.

“And you,” she concluded to the conductor, “give me eightpence, then we shall be all right.”

The conductor gave her the eightpence – the sixpence he had taken from the first lady, with a penny and two halfpennies out of his own bag – distrustfully, and retired, muttering something about calculation.

“Now,” said the elder lady to the younger, “I owe you a shilling.”

I thought the incident closed, when suddenly a florid gentleman on the opposite seat said loudly:–

“Hi, conductor! you’ve cheated these ladies out of fourpence.”

“What about fourpence, then?” replied the indignant conductor from the top of the steps, “it was a twopenny fare.”

“Two twopences don’t make eightpence,” retorted the florid gentleman hotly. “How much did you give the conductor, my dear?” he asked the first of the young ladies.

“I gave him sixpence,” replied the lady. “And then I gave you fourpence, you know,” she said to her companion.

“Expensive tickets, aren’t they?” noticed a common-looking man on the seat behind.

“Oh, that’s impossible, dear,” returned the other, “because I owed you sixpence in the beginning.”

“But I did,” persisted the first lady.

“You gave me a shilling,” said the conductor, who had returned. He was pointing an accusing forefinger at the elder of the ladies.

The elder lady nodded.

“And I gave you sixpence and two pennies, didn’t I?”

The lady admitted it.

“And I gave her” – he pointed towards the younger lady – “fourpence, didn’t I?”

“Which I gave you, you know, dear,” remarked the younger lady.

“So, that’s me!… That’s me!… You cheated me out of the fourpence,” cried the conductor.

“But,” said the florid gentleman, “the other lady gave you sixpence.”

“Which I give to her,” replied the conductor. He pointed again his finger at the elder lady. “You can search my bag if you like. I do not have that sixpence on me!”

By this time everybody had forgotten what they had done, and contradicted themselves and one another. The conductor had called a policeman and had taken the names and addresses of the two ladies, intending to sue them for the fourpence (which they wanted to pay, but which the florid man did not allow them to do). The younger lady became convinced that the elder lady wanted to cheat her, and the elder lady was in tears.

The florid gentleman and myself continued to Charing Cross Station. At the booking office window I learned that we were buying the tickets for the same station, and we journeyed together. He talked about the fourpence all the way.

At my gate we shook hands, and he expressed delight at the discovery that we were neighbours. What attracted him to myself I did not understand, because he had bored me considerably. Later I learned that he was charmed with anyone who did not openly insult him.

Three days afterwards he burst into my study.

“I met the postman as I was walking,” he said, and gave me a blue envelope, “and he gave me this, for you.”

I saw it was an application for the water-rate.

“But look,” he continued. “That’s for water to the 29th September. You’ve no right to pay it in June.”

I replied that I must pay water-rates, and that it not important whether I pay in June or September.

“That’s not it,” he answered, “it’s the principle of the thing. Why will you pay for water you have never had? That’s not fair! You pay for what you don’t owe!”

He was a good talker, and I was silly enough to listen to him. By the end of half an hour he had persuaded me that the question was connected with the rights of man, and that if I pay that fourteen and tenpence in June instead of in September, I will be unworthy of my parents.

He showed me that the company was absolutely wrong, and I sat down and wrote an insulting letter to the chairman.

The secretary replied that they would treat it as a test case, and presumed that my solicitors would accept service on my behalf.

When I showed him this letter he was delighted.

“You leave it to me,” he said, “and we’ll teach them a lesson.”

I left it to him. My only excuse is that at the time I was very busy. I was writing a play. The little sense that I possessed, I suppose, was absorbed by the play.

The magistrate’s decision damped my words, but he became even more courageous. Magistrates, he said, were old fools. This was a matter for a judge.

The judge was a kindly old gentleman, and said he did not think he could allow the company their costs, so that, I paid only fifty pounds: original fourteen and tenpence.

Afterwards our friendship waned, but we were living in the same suburb, I saw him quite often.

At parties of all kinds he was particularly prominent, and on such occasions, when he was in his most good-natured mood, he was especially dangerous. No man worked harder for the enjoyment of others.

One Christmas afternoon I visited a friend. And I found fourteen or fifteen elderly ladies and gentlemen round a row of chairs in the centre of the drawing-room while Poppleton played the piano. From time to time they changed their places and one person was leaving the room. I stood by the door and was watching the weird scene. Presently an escaped guest came towards me, and I asked him what the ceremony meant.

“Don’t ask me,” he answered. “Some of Poppleton’s damned tomfoolery.” Then he added, “We will play forfeits after this.”

The servant was still waiting a favourable opportunity to announce me. I gave her a shilling and asked not to do that, then I got away.

Poppleton knew enough games to open a small club. Just as you were in the middle of an interesting discussion, or a delightful conversation with a pretty woman, he liked to appear and say: “Come along, we’re going to play literary consequences. He was dragging you to the table, and putting a piece of paper and a pencil before you. He was asking you to write a description of your favourite heroine in fiction, and he checked if you really did it.

He worked a lot. It was always he who volunteered to escort the old ladies to the station, and who never left them until he had placed them safely into the wrong train. He played “wild beasts” with the children, and frighten them enormously.

So he was the kindest man in the world. He never visited poor sick persons without something in his pocket, some little delicacy which was forbidden by the doctor and which mad them worse. He loved to manage a wedding. Once he planned matters so that the bride arrived three-quarters of an hour before the groom, and that was a terrible day for her, and once he forgot the clergyman. But he was always ready to admit when he made a mistake.

At funerals, also, he was pointing out to the grief-stricken relatives how much better it was for all that the man was dead, and expressing a pious hope that they would soon join him.

The best delight of his life, however, was to take part in other people’s quarrels. No quarrel was complete without him. He generally came in as mediator, and finished as a witness.

As a journalist or politician his wonderful grasp of other people’s business could help him a lot. But the error he made was like this: he was trying to work it out in practice.