The Honour of Israel Gow

(Честь Израэля Гау)

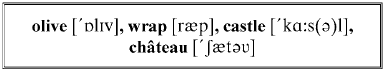

A stormy evening of olive and silver was closing in (наступал оливково-серебристый вечер, /предвещавший/ ненастье; storm – буря; гроза; to close in – приближаться; наступать; silver – серебро), as Father Brown, wrapped in a grey Scotch plaid (когда отец Браун, укутанный в серый шотландский плед; to wrap – завертывать; закутывать; Scotch – шотландский), came to the end of a grey Scotch valley and beheld the strange castle of Glengyle (дошел до конца серой шотландской низины и увидел странный замок Гленгайл; valley – долина; низина; to behold – увидеть; castle – замок). It stopped one end of the glen or hollow like a blind alley (замок: «он» стоял на одном краю долины или низины, образуя тупик: «как тупик»; to stop – останавливаться; прекращаться; преграждать; glen – узкая горная долина; hollow – пустота; низина; blind alley – безвыходное положение; тупик; blind – слепой); and it looked like the end of the world (похожий на край света; to look like – быть похожим; world – мир; свет). Rising in steep roofs and spires of seagreen slate in the manner of the old French-Scotch châteaux (поднимаясь вверх непомерно высокими шпилями и крышами из шифера цвета морской волны наподобие старинных замков французов и шотландцев; to rise – восходить; вставать; подниматься; steep – крутой; чрезмерный; непомерно высокий; sea – море; slate – сланец; шифер; manner – метод; способ; стиль), it reminded an Englishman of the sinister steeple-hats of witches in fairy tales (замок напоминал англичанину о зловещих остроконечных колпаках ведьм из сказок; to remind of – напоминать; sinister – зловещий; steeple – колокольня; шпиль; острие; fairy tale – волшебная сказка) and the pine woods that rocked round the green turrets looked, by comparison, as black as numberless flocks of ravens (а сосновый лес, который окружал зеленые башенки: «покачивался вокруг зеленых башенок», выглядел /рядом с замком/, таким черным, как бесчисленные стаи воронов; pine – сосна; to rock – качаться; turret – башенка; comparison – сравнение; number – число; – less – суффикс, обозначающий «лишенный чего-либо», «не имеющий чего-либо»; flock – клок; пучок; стадо; стая; raven – ворон).

A stormy evening of olive and silver was closing in, as Father Brown, wrapped in a grey Scotch plaid, came to the end of a grey Scotch valley and beheld the strange castle of Glengyle. It stopped one end of the glen or hollow like a blind alley; and it looked like the end of the world. Rising in steep roofs and spires of seagreen slate in the manner of the old French-Scotch châteaux, it reminded an Englishman of the sinister steeple-hats of witches in fairy tales; and the pine woods that rocked round the green turrets looked, by comparison, as black as numberless flocks of ravens.

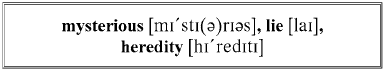

This note of a dreamy, almost a sleepy devilry, was no mere fancy from the landscape (это ощущение: «этот признак» смутной, почти сонной дьявольщины, не было пустой фантазией, /навеянной/ пейзажем; note – заметка; примечание; отличительный признак; dreamy – полный сновидений; неясный; devil – дьявол; mere – простой; не более чем; всего лишь). For there did rest on the place one of those clouds of pride and madness and mysterious sorrow (поскольку над этим местом /действительно/ висела: «отдыхала» одна из тех туч гордыни и сумасшествия и таинственной скорби; cloud – облако; туча; mystery – тайна) which lie more heavily on the noble houses of Scotland than on any other of the children of men (которые в большей степени простираются: «лежат» над домами знати в Шотландии, чем над другими /домами/, где живут дети /простых/ людей; to lie – лежать; находиться; heavily – тяжело; в большой степени; noble – человек благородного происхождения; дворянин). For Scotland has a double dose of the poison called heredity (ведь для Шотландии характерна двойная доза яда, называемого наследственностью: «Шотландия имеет…»; heredity – наследственность; heir – наследник; heiress – наследница); the sense of blood in the aristocrat, and the sense of doom in the Calvinist (чувство высокого происхождения: «чувство крови» у аристократов и чувство рока = предопределенности у кальвинистов; sense – чувство; doom – рок; Day of the Doom – день Страшного суда).

This note of a dreamy, almost a sleepy devilry, was no mere fancy from the landscape. For there did rest on the place one of those clouds of pride and madness and mysterious sorrow which lie more heavily on the noble houses of Scotland than on any other of the children of men. For Scotland has a double dose of the poison called heredity; the sense of blood in the aristocrat, and the sense of doom in the Calvinist.

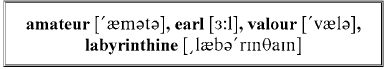

The priest had snatched a day from his business at Glasgow to meet his friend Flambeau, the amateur detective (священник с трудом оторвался от дел в Глазго на сутки: «ухватил день», чтобы встретиться со своим другом Фламбо, сыщиком-любителем; to meet – встречать/ся/; знакомить/ся/; amateur – любитель) who was at Glengyle Castle with another more formal officer investigating the life and death of the late Earl of Glengyle (который был в замке Гленгайл вместе с сыщиком-профессионалом: «другим более официальным сыщиком», и /они/ расследовали /обстоятельства/ жизни и смерти покойного графа Гленгайла; officer – чиновник; офицер; полицейский; to investigate – расследовать). That mysterious person was the last representative of a race whose valour, insanity, and violent cunning had made them terrible even among the sinister nobility of their nation in the sixteenth century (этот таинственный человек был последним представителем рода, чьи отвага, безумие и неистовое коварство выделяло его /этот род/ даже среди мрачной знати шотландцев в XVI веке; mystery – тайна, загадка; representative – образец; представитель; sinister – зловещий, мрачный; nobility – родовая знать). None were deeper in that labyrinthine ambition, in chamber within chamber of that palace of lies that was built up around Mary Queen of Scots (никто не пошел далее /чем Гленгайлы/: «никто не был глубже» в тот лабиринт честолюбия, в те анфилады дворца лжи, возведенные вокруг Марии, королевы шотландцев; deep – глубокий; ambition – честолюбие; ambitious – честолюбивый; chamber – комната; within – в; внутри; lie – ложь; to build up – воздвигать).

The priest had snatched a day from his business at Glasgow to meet his friend Flambeau, the amateur detective, who was at Glengyle Castle with another more formal officer investigating the life and death of the late Earl of Glengyle. That mysterious person was the last representative of a race whose valour, insanity, and violent cunning had made them terrible even among the sinister nobility of their nation in the sixteenth century. None were deeper in that labyrinthine ambition, in chamber within chamber of that palace of lies that was built up around Mary Queen of Scots.

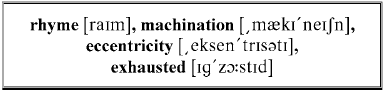

The rhyme in the country-side attested the motive and the result of their machinations candidly (о причине и результате их козней откровенно свидетельствовал стишок, /известный/ в округе; rhyme – рифма; рифмованный стих; to attest – подтверждать; свидетельствовать; motive – мотив; причина; machination – плетение интриг; козни; candidly – открыто, откровенно):

As green sap to the summer trees (как зеленый сок/живица/сила /добавляется/ к летним деревьям; summer – летний)

Is red gold to the Ogilvies (так и красное золото /добавляется/ к /богатству семейства/ Оджилви).

For many centuries there had never been a decent lord in Glengyle Castle (в течение многих веков в замке Гленгайл не было ни одного достойного господина; century – столетие, век; decent – приличный; порядочный; lord – господин); and with the Victorian era one would have thought that all eccentricities were exhausted (с приходом викторианской эпохи могло показаться, что все странности исчерпали себя; one would think – казалось бы; eccentricity – эксцентричность, странность; to exhaust – исчерпывать). The last Glengyle, however, satisfied his tribal tradition by doing the only thing that was left for him to do; he disappeared (последний /из рода/ Гленгайл, однако, поддержал: «выполнил» семейную традицию, сделав единственную вещь, которая оставалась для него: он исчез; to satisfy – удовлетворять; соответствовать; выполнять; tribal – родовой; семейный; to leave; to appear – показываться; появляться; to disappear – исчезать). I do not mean that he went abroad (я не имею в виду, что он уехал за границу); by all accounts he was still in the castle (судя по всему: «по всеобщему признанию», он все еще был в замке; account – счет; отчет; мнение; оценка), if he was anywhere (если вообще он где-нибудь был). But though his name was in the church register and the big red Peerage (но хотя его имя значилось: «было» в церковных книгах и в большой красной книге пэров; register – журнал записей; книга учета), nobody ever saw him under the sun (никто на свете никогда не видел его самого; under the sun – в этом мире; на свете: «под солнцем»; sun – солнце).

The rhyme in the country-side attested the motive and the result of their machinations candidly:

As green sap to the summer trees

Is red gold to the Ogilvies.

For many centuries there had never been a decent lord in Glengyle Castle; and with the Victorian era one would have thought that all eccentricities were exhausted. The last Glengyle, however, satisfied his tribal tradition by doing the only thing that was left for him to do; he disappeared. I do not mean that he went abroad; by all accounts he was still in the castle, if he was anywhere. But though his name was in the church register and the big red Peerage, nobody ever saw him under the sun.

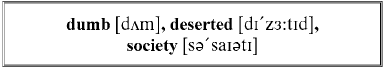

If anyone saw him it was a solitary man-servant, something between a groom and a gardener (если кто его и видел, то это был отшельник-слуга, выполнявший обязанности конюха и садовника: «что-то между конюхом и садовником»; solitary – одиночный; отшельник; man – человек; мужчина; servant – прислуга). He was so deaf that the more business-like assumed him to be dumb (он /слуга/ был таким глухим, что более деловые люди считали его немым; to assume – принимать; предполагать); while the more penetrating declared him to be half-witted (в то время как более прозорливые объявляли его слабоумным; while – пока; в то время как; penetrating – проникающий; проницательный; half-witted – слабоумный; wit – остроумие; разум). A gaunt, red-haired labourer, with a dogged jaw and chin, but quite blank blue eyes (сухопарый рыжеволосый труженик с упрямым подбородком: «упрямой челюстью и подбородком» и абсолютно бессмысленными голубыми глазами; labourer – /неквалифицированный/ рабочий; labour – труд; blank – пустой; чистый; бессмысленный /о взгляде/), he went by the name of Israel Gow (он был известен под именем Израэля Гау; to go by the name – слыть; быть известным под именем), and was the one silent servant on that deserted estate (и он был единственным немым слугой в том заброшенном поместье; silent – безмолвный, молчаливый; silence – тишина; безмолвие; desert – пустыня; estate – поместье). But the energy with which he dug potatoes (но рвение: «энергия», с которым он копал картошку; to dig), and the regularity with which he disappeared into the kitchen (и регулярность, с которой он исчезал в кухне) gave people an impression that he was providing for the meals of a superior (создавало у людей впечатление, что он снабжает едой хозяина; to give – давать; to provide with – снабжать; обеспечивать; superior – глава; начальник), and that the strange earl was still concealed in the castle (и что странного графа все еще прячут в замке). If society needed any further proof that he was there (если /обществу/ требовались дополнительные доказательства, что он был там), the servant persistently asserted that he was not at home (то слуга неизменно отвечал, что хозяина: «его» нет дома; persistent – постоянный, стабильный, неизменный).

If anyone saw him it was a solitary man-servant, something between a groom and a gardener. He was so deaf that the more business-like assumed him to be dumb; while the more penetrating declared him to be half-witted. A gaunt, red-haired labourer, with a dogged jaw and chin, but quite blank blue eyes, he went by the name of Israel Gow, and was the one silent servant on that deserted estate. But the energy with which he dug potatoes, and the regularity with which he disappeared into the kitchen gave people an impression that he was providing for the meals of a superior, and that the strange earl was still concealed in the castle. If society needed any further proof that he was there, the servant persistently asserted that he was not at home.

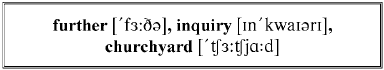

One morning the provost and the minister (for the Glengyles were Presbyterian) were summoned to the castle (однажды утром мэра города и пастора (ибо Гленгайлы принадлежали к пресвитерианской церкви: «были пресвитерианцами») позвали в замок; to summon – вызвать; позвать; minister – министр; посланник; священник). There they found that the gardener, groom and cook had added to his many professions that of an undertaker (там они обнаружили, что садовник, конюх и повар добавил к своим многим профессиям и /профессию/ гробовщика; to find – находить, обнаруживать), and had nailed up his noble master in a coffin (и заколотил в гроб своего высокородного хозяина; to nail up – заколачивать; nail – ноготь; гвоздь). With how much or how little further inquiry this odd fact was passed (в какой степени: «много или мало» продвигалось дальнейшее расследование этого странного случая; inquiry – вопрос; запрос; расследование; fact – обстоятельство; факт; событие; случай), did not as yet very plainly appear (не было пока на данный момент /очень/ понятно; as yet – пока; на данный момент; plainly – ясно); for the thing had never been legally investigated (поскольку этот случай никогда не расследовался официально; thing – вещь; ситуация; legal – правовой; судебный; законный; investigation – расследование) till Flambeau had gone north two or three days before (пока Фламбо, дня через два-три, не отправился на север; before – впереди; вперед; до, раньше /указывает на предшествование во времени/). By then the body of Lord Glengyle (if it was the body) had lain for some time in the little churchyard on the hill (к тому времени тело графа Гленгайла (если то было его тело) покоилось: «пролежало» на маленьком церковном кладбище, на холме, в течение некоторого времени; to lie; church – церковь; yard – ярд; внутренний двор).

One morning the provost and the minister (for the Glengyles were Presbyterian) were summoned to the castle. There they found that the gardener, groom and cook had added to his many professions that of an undertaker, and had nailed up his noble master in a coffin. With how much or how little further inquiry this odd fact was passed, did not as yet very plainly appear; for the thing had never been legally investigated till Flambeau had gone north two or three days before. By then the body of Lord Glengyle (if it was the body) had lain for some time in the little churchyard on the hill.

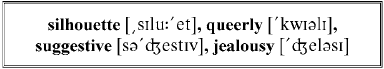

As Father Brown passed through the dim garden and came under the shadow of the château (когда отец Браун прошел через сумрачный сад и подошел к замку, отбрасывающему тень: «вошел в тень от замка»; dim – тусклый; неяркий; to pass through – проходить сквозь; under – у; около; под), the clouds were thick and the whole air damp and thundery (тучи сгустились, а /весь/ воздух был влажным и предвещал грозу: «грозовым»; thunder – гром; thundery – грозовой, предвещающий грозу). Against the last stripe of the green-gold sunset he saw a black human silhouette (на фоне последней полоски золотисто-зеленого заката он увидел черный силуэт человека; sunset – заход солнца; закат); a man in a chimney-pot hat, with a big spade over his shoulder (человека в цилиндре, с большой лопатой на плече; chimney-pot hat – цилиндр; chimney-pot – колпак дымовой трубы; chimney – труба; pot – горшок; котелок; spade – лопата; shoulder – плечо). The combination was queerly suggestive of a sexton (такое нелепое сочетание напоминало о могильщике; queerly – странно, необычно; sexton – церковный сторож; пономарь; могильщик); but when Brown remembered the deaf servant who dug potatoes, he thought it natural enough (но когда отец Браун припомнил глухого слугу, который копал картошку, он подумал, что все достаточно естественно). He knew something of the Scotch peasant (он знал кое-что о шотландском крестьянине); he knew the respectability which might well feel it necessary to wear “blacks” for an official inquiry (он знал о благоприличии, которое вполне могло подсказать: «почувствовать», что необходимо надеть черную /одежду/ для официального расследования; to respect – уважать; почитать; чтить); he knew also the economy that would not lose an hour’s digging for that (он также знал о расчетливости, которая не потеряет и часа /который можно было бы уделить выкапыванию картофеля/ в связи с этим). Even the man’s start and suspicious stare as the priest went by were consonant enough with the vigilance and jealousy of such a type (даже то, как человек /слуга/ вздрогнул и недоверчиво пристально глядел на проходящего священника, прекрасно увязывалось: «согласовывалось» с настороженностью и беспокойством человека такого типа; suspicious – подозрительный; недоверчивый; consonant – согласный; совпадающий; совместимый; vigilance – бдительность, настороженность; jealousy – ревность; зависть; подозрительность; беспокойство).

As Father Brown passed through the dim garden and came under the shadow of the château, the clouds were thick and the whole air damp and thundery. Against the last stripe of the green-gold sunset he saw a black human silhouette; a man in a chimney-pot hat, with a big spade over his shoulder. The combination was queerly suggestive of a sexton; but when Brown remembered the deaf servant who dug potatoes, he thought it natural enough. He knew something of the Scotch peasant; he knew the respectability which might well feel it necessary to wear “blacks” for an official inquiry; he knew also the economy that would not lose an hour’s digging for that. Even the man’s start and suspicious stare as the priest went by were consonant enough with the vigilance and jealousy of such a type.

The great door was opened by Flambeau himself (парадная: «большая» дверь была открыта самим Фламбо), who had with him a lean man with iron-grey hair and papers in his hand: Inspector Craven from Scotland Yard (рядом с ним был худой седой человек: «с волосами с проседью» и с бумагами в руке: инспектор Крейвен из Скотленд-Ярда; iron-grey hair – волосы с проседью). The entrance hall was mostly stripped and empty (в зале почти не было мебели: «холл был по большей части обнажен и пуст»; stripped – ободранный; раздетый; empty – пустой); but the pale, sneering faces of one or two of the wicked Ogilvies looked down out of black periwigs and blackening canvas (но с темных холстов из-под темных париков смотрели свысока бледные насмешливые лица одного-двух отвратительных Оджилви; to sneer – презрительно или насмешливо улыбаться; wicked – злой; злобный; отвратительный; to look down – смотреть свысока; canvas – холст; паруса; полотно; картина).

The great door was opened by Flambeau himself, who had with him a lean man with iron-grey hair and papers in his hand: Inspector Craven from Scotland Yard. The entrance hall was mostly stripped and empty; but the pale, sneering faces of one or two of the wicked Ogilvies looked down out of black periwigs and blackening canvas.

Following them into an inner room (проследовав за ними во внутреннюю комнату; to follow – следовать; идти за), Father Brown found that the allies had been seated at a long oak table (отец Браун увидел: «обнаружил», что все официальные лица: «союзники» сидели за длинным дубовым столом; to find; ally – друг, союзник; oak – дуб), of which their end was covered with scribbled papers, flanked with whisky and cigars (тот конец /стола, где они работали/ был покрыт исписанными бумагами и расположенными по бокам /бутылками/ виски и сигарами; to cover – покрывать; to scribble – писать быстро и небрежно; to flank – быть расположенным сбоку; располагаться по обе стороны). Through the whole of its remaining length it was occupied by detached objects arranged at intervals (на всей оставшейся длине стола с интервалами обособленно располагались предметы; to remain – оставаться; detached – отдельный; обособленный; to arrange – приводить в порядок; расставлять; систематизировать); objects about as inexplicable as any objects could be (предметы столь же необъяснимые, как любые /другие/ предметы /могли быть/ = предметы, назначение которых было довольно трудно объяснить; inexplicable – необъяснимый). One looked like a small heap of glittering broken glass (один выглядел как маленькая куча сверкающих стеклянных осколков: «сверкающего сломанного стекла»; heap – груда; куча; to break). Another looked like a high heap of brown dust (другой выглядел как высокая куча пыли коричневого цвета: «кучка коричневой пыли»). A third appeared to be a plain stick of wood (а в третьей была /только/ простая деревянная палка: «палка из дерева»; to appear – показываться; появляться /в наличии/).

Following them into an inner room, Father Brown found that the allies had been seated at a long oak table, of which their end was covered with scribbled papers, flanked with whisky and cigars. Through the whole of its remaining length it was occupied by detached objects arranged at intervals; objects about as inexplicable as any objects could be. One looked like a small heap of glittering broken glass. Another looked like a high heap of brown dust. A third appeared to be a plain stick of wood.

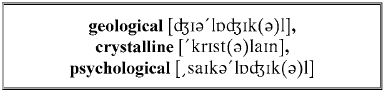

“You seem to have a sort of geological museum here (похоже, у вас тут разновидность геологического музея),” he said, as he sat down, jerking his head briefly in the direction of the brown dust and the crystalline fragments (сказал он усаживаясь, резко показав головой в сторону коричневой пыли и кристаллических осколков; to jerk – резко толкать, дергать; делать резкое движение).

“Not a geological museum (не геологический музей),” replied Flambeau (ответил Фламбо; to reply – отвечать); “say a psychological museum (скажем: «скорее» психологический /музей/).”

“Oh, for the Lord’s sake (ради Бога; for God’s sake – ради бога, ради всего святого),” cried the police detective laughing (воскликнул сыщик из полиции, смеясь), “don’t let’s begin with such long words (давайте уж не будем начинать с таких длинных слов).”

“Don’t you know what psychology means (разве вы не знаете, что означает /слово/ «психология»)?” asked Flambeau with friendly surprise (спросил Фламбо с дружелюбным удивлением). “Psychology means being off your chump («психология» означает быть «ку-ку»; to be off one’s chump – «того», с приветом, «ку-ку»: «быть/оказаться вне своей башки»; chump – колода; башка).”

“Still I hardly follow (по-прежнему не совсем понимаю; hardly – едва; почти не; с трудом; to follow – следовать; ясно понимать),” replied the official (ответил инспектор: «должностное лицо»).

“Well,” said Flambeau, with decision (ну, сказал Фламбо решительно; decision – решение; решимость; to decide – решать; принимать решение), “I mean that we’ve only found out one thing about Lord Glengyle (я имею в виду, что мы выяснили одну вещь о лорде Гленгайле; to find – находить, обнаруживать; to find out – выяснять). He was a maniac (он был маньяком).”

“You seem to have a sort of geological museum here,” he said, as he sat down, jerking his head briefly in the direction of the brown dust and the crystalline fragments.

“Not a geological museum,” replied Flambeau; “say a psychological museum.”

“Oh, for the Lord’s sake,” cried the police detective laughing, “don’t let’s begin with such long words.”

“Don’t you know what psychology means?” asked Flambeau with friendly surprise. “Psychology means being off your chump.”

“Still I hardly follow,” replied the official.

“Well,” said Flambeau, with decision, “I mean that we’ve only found out one thing about Lord Glengyle. He was a maniac.”

The black silhouette of Gow with his top hat and spade passed the window (Гау с цилиндром /на голове/ и лопатой прошел мимо окна, как черный силуэт: «черный силуэт Гау с цилиндром и лопатой прошел мимо окна»), dimly outlined against the darkening sky (смутно обрисованный на фоне темнеющего неба; to outline – нарисовать контур; очертить; обрисовать). Father Brown stared passively at it and answered (отец Браун посмотрел на него безучастно и ответил; to stare – пристально глядеть):

“I can understand there must have been something odd about the man (я понимаю, должно быть, этот человек был со странностями: «было что-то странное в нем»), or he wouldn’t have buried himself alive – nor been in such a hurry to bury himself dead (иначе он не похоронил бы себя заживо и не /велел бы/ похоронить так быстро /себя/ после смерти; to bury – хоронить; to be in a hurry – спешить; торопиться; dead – мертвый; умерший). But what makes you think it was lunacy (почему вы думаете, что он был сумасшедший: «что заставляет вас думать, что это было умопомешательство»; lunacy – лунатизм; безумие; /умо/помешательство)?”

The black silhouette of Gow with his top hat and spade passed the window, dimly outlined against the darkening sky Father Brown stared passively at it and answered:

“I can understand there must have been something odd about the man, or he wouldn’t have buried himself alive – nor been in such a hurry to bury himself dead. But what makes you think it was lunacy?”

“Well,” said Flambeau, “you just listen to the list of things Mr. Craven has found in the house (послушайте, что мистер Крейвен нашел в этом доме; list – список; перечень).”

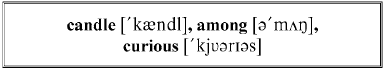

“We must get a candle (мы должны взять свечку),” said Craven, suddenly (сказал Крейвен неожиданно). “A storm is getting up, and it’s too dark to read (надвигается шторм, слишком темно, чтобы читать; to get up – подниматься; вставать; усиливаться).”

“Have you found any candles (а свечки вы нашли),” asked Brown smiling (спросил отец Браун, улыбаясь), “among your oddities (среди /ваших/ странных вещей)?”

Flambeau raised a grave face, and fixed his dark eyes on his friend (Фламбо серьезно посмотрел на своего друга, устремив на него взгляд темных глаз: «поднял серьезное лицо и устремил взгляд темных глаз на своего друга»; to fix on /smth., smb./ – устремлять, сосредоточивать /взгляд, внимание на ком-л., чем-л./; to fix – закреплять).

“That is curious, too (это тоже интересно; curious – любопытно),” he said. “Twenty-five candles, and not a trace of a candlestick (/здесь/ двадцать пять свечей и ни одного подсвечника: «ни следа подсвечника).”

“Well,” said Flambeau, “you just listen to the list of things Mr. Craven has found in the house.”

“We must get a candle,” said Craven, suddenly. “A storm is getting up, and it’s too dark to read.”

“Have you found any candles,” asked Brown smiling, “among your oddities?”

Flambeau raised a grave face, and fixed his dark eyes on his friend.

“That is curious, too,” he said. “Twenty-five candles, and not a trace of a candlestick.”

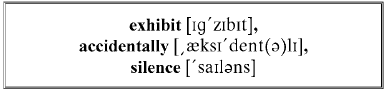

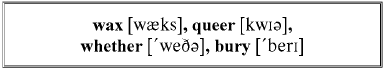

In the rapidly darkening room and rapidly rising wind (в комнате быстро темнело, а за окном быстро поднимался ветер: «в быстро темнеющей комнате и быстро поднимающемся ветре /снаружи/»; rapid – быстрый), Brown went along the table to where a bundle of wax candles lay among the other scrappy exhibits (отец Браун прошел вдоль стола туда, где лежала связка вощеных свечей среди других разрозненных вещественных доказательств; bundle – узел; связка; exhibit – экспонат /на выставке/; вещественное доказательство). As he did so he bent accidentally over the heap of red-brown dust (проходя: «когда он делал это», он неосторожно нагнулся над буро-красной кучей; to bend); and a sharp sneeze cracked the silence (и он сильно чихнул в тишине; sharp – острый; резкий; пронзительный; to sneeze – чихать; to crack – скрежетать; трещать; производить шум).

“Hullo (эге; hullo – приветствие; оклик; восклицание; удивление)!” he said, “snuff (/да это же/ нюхательный табак)!”

He took one of the candles, lit it carefully, came back and stuck it in the neck of the whisky bottle (он взял одну из свечей, аккуратно зажег ее, вернулся и вставил в горлышко бутылки из-под виски; to light; to stick; neck – шея; ворот; горлышко /бутылки/). The unrestful night air, blowing through the crazy window, waved the long flame like a banner (беспокойный ночной ветер, дующий через старое окно, заставил длинное пламя колыхаться, как знамя; unrest – беспокойство; тревога; волнение; crazy – ненормальный; сумасшедший; сделанный из кусков различной формы; непрочный; разваливающийся; to wave – вызывать или совершать разнообразные движения; развеваться /о флагах/). And on every side of the castle they could hear the miles and miles of black pine wood seething like a black sea around a rock (а на мили и мили вокруг с каждой стороны замка они могли слышать шум: «волнение» /леса/ черных сосен, словно темное море /било/ о скалу; to seethe – бурлить, кипеть).

In the rapidly darkening room and rapidly rising wind, Brown went along the table to where a bundle of wax candles lay among the other scrappy exhibits. As he did so he bent accidentally over the heap of red-brown dust; and a sharp sneeze cracked the silence.

“Hullo!” he said, “snuff!”

He took one of the candles, lit it carefully, came back and stuck it in the neck of the whisky bottle. The unrestful night air, blowing through the crazy window, waved the long flame like a banner. And on every side of the castle they could hear the miles and miles of black pine wood seething like a black sea around a rock.

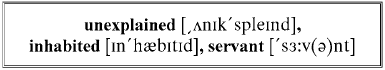

“I will read the inventory (я прочитаю опись),” began Craven gravely, picking up one of the papers (серьезно начал Крейвен и взял одну из бумаг; to begin; to pick up – поднимать), “the inventory of what we found loose and unexplained in the castle (опись того, что мы нашли в замке свободно лежащим и необъяснимым; to explain – объяснять). You are to understand that the place generally was dismantled and neglected (поясню: «вам следует понять», что это место в целом было нежилым и заброшенным; dismantled – разобранный; демонтированный; neglected – заброшенный; запущенный); but one or two rooms had plainly been inhabited in a simple but not squalid style by somebody (но в одной или двух комнатах кто-то определенно жил – скромно, но не убого; plainly – ясно; отчетливо; очевидно; to inhabit – жить; обитать; simple – несложный; простой; скромный; без излишеств; squalid – грязный; запущенный; убогий); somebody who was not the servant Gow (этот кто-то не слуга Гау). The list is as follows (список следующий; as follows – следующее; как изложено ниже):

“I will read the inventory,” began Craven gravely, picking up one of the papers, “the inventory of what we found loose and unexplained in the castle. You are to understand that the place generally was dismantled and neglected; but one or two rooms had plainly been inhabited in a simple but not squalid style by somebody; somebody who was not the servant Gow. The list is as follows:

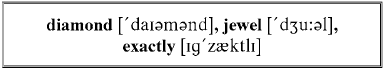

“First item (первый пункт; item – пункт; параграф; статья). A very considerable hoard of precious stones, nearly all diamonds, and all of them loose, without any setting whatever (довольно значительный запас драгоценных камней, почти все бриллианты, /лежат/ россыпью, без какой-либо оправы; hoard – запас; precious – драгоценный; loose – свободный; несвязанный; setting – огранка; оправа /камня/). Of course, it is natural that the Ogilvies should have family jewels (конечно, это неудивительно: «естественно», что у Оджилви были семейные драгоценности; jewel – драгоценный камень; ювелирное изделие); but those are exactly the jewels that are almost always set in particular articles of ornament (но такие драгоценности практически всегда оправляют в особенные изделия-украшения; to set – ставить; класть; размещать; разворачиваться; происходить; оправлять, вставлять в оправу /драгоценные камни/). The Ogilvies would seem to have kept theirs loose in their pockets, like coppers (в семье Оджилви их, по-видимому, носили в карманах, как мелочь; to keep – держать; would – служебный глагол, выражающий привычное действие, относящееся к прошедшему; copper – медь; мелкая монета).

“First item. A very considerable hoard of precious stones, nearly all diamonds, and all of them loose, without any setting whatever. Of course, it is natural that the Ogilvies should have family jewels; but those are exactly the jewels that are almost always set in particular articles of ornament. The Ogilvies would seem to have kept theirs loose in their pockets, like coppers.

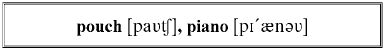

“Second item (второй пункт). Heaps and heaps of loose snuff, not kept in a horn, or even a pouch, but lying in heaps on the mantelpieces, on the sideboard, on the piano, anywhere (много: «уйма» нюхательного табака россыпью, который не хранился в табакерках: «контейнерах» или даже в мешочках, но лежал кучками на каминных досках, на буфете, на пианино, везде; heaps – масса; уйма; много; to keep; horn – рог; гудок; мыс; труба; контейнер; pouch – сумка; мешочек; mantelpiece – каминная доска; sideboard – буфет). It looks as if the old gentleman would not take the trouble to look in a pocket or lift a lid (похоже, что: «это выглядит так, словно» старый джентльмен даже не утруждался залезть в карман или поднять крышку /табакерки/; to take the trouble – потрудиться; to lift – поднимать; lid – крышка).

“Second item. Heaps and heaps of loose snuff, not kept in a horn, or even a pouch, but lying in heaps on the mantelpieces, on the sideboard, on the piano, anywhere. It looks as if the old gentleman would not take the trouble to look in a pocket or lift a lid.

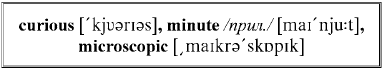

“Third item (третий пункт). Here and there about the house curious little heaps of minute pieces of metal, some like steel springs and some in the form of microscopic wheels (здесь и там по дому разбросаны любопытные маленькие кучки металла, некоторые похожи на стальные пружинки, другие имеют форму микроскопических колесиков; here and there – там и сям, кое-где, местами; разбросанно; spring – пружина; wheel – колесо; колесико). As if they had gutted some mechanical toy (как будто они разобрали механическую игрушку; to gut – потрошить /рыбу, курицу/; уничтожать внутреннюю часть /чего-л./; toy – забава; игрушка).

“Third item. Here and there about the house curious little heaps of minute pieces of metal, some like steel springs and some in the form of microscopic wheels. As if they had gutted some mechanical toy.

“Fourth item (четвертый пункт). The wax candles, which have to be stuck in bottle necks because there is nothing else to stick them in (восковые свечи, которые приходится вставлять в горлышко бутылок, потому что больше вставлять их не во что; wax – воск; candle – свеча; neck – шея; ворот; горлышко /бутылки/). Now I wish you to note how very much queerer all this is than anything we anticipated (хочу обратить ваше внимание, насколько все это более странно, чем мы предполагали; to note – замечать; обращать внимание; queer – странный; to anticipate – ожидать). For the central riddle we are prepared (к основной загадке мы /были/ готовы); we have all seen at a glance that there was something wrong about the last earl (с самого начала было понятно, что с последним графом что-то не так; at a glance – сразу; с первого взгляда; wrong – неправильный). We have come here to find out whether he really lived here (мы пришли сюда, чтобы выяснить, действительно ли он жил здесь; to find out – разузнать; выяснить; whether – ли /вводит косвенный вопрос/), whether he really died here (действительно ли он умер здесь), whether that red-haired scarecrow who did his burying had anything to do with his dying (имеет ли это рыжеволосое пугало, которое его похоронило, отношение к его смерти; scarecrow – пугало; to scare – пугать; crow – ворона; to bury – хоронить; dying – умирание; смерть). But suppose the worst in all this, the most lurid or melodramatic solution you like (но предположим самое худшее /из всех/, самое страшное или театральное объяснение, какое вам нравится; to suppose – полагать; предполагать; lurid – сенсационный; страшный; solution – решение; разъяснение; to solve – решать).

“Fourth item. The wax candles, which have to be stuck in bottle necks because there is nothing else to stick them in. Now I wish you to note how very much queerer all this is than anything we anticipated. For the central riddle we are prepared; we have all seen at a glance that there was something wrong about the last earl. We have come here to find out whether he really lived here, whether he really died here, whether that red-haired scarecrow who did his burying had anything to do with his dying. But suppose the worst in all this, the most lurid or melodramatic solution you like.

Suppose the servant really killed the master, or suppose the master isn’t really dead (предположим, слуга действительно убил хозяина, или, предположим, хозяин жив: «на самом деле не мертв»), or suppose the master is dressed up as the servant, or suppose the servant is buried for the master (или предположим, хозяин /теперь/ одет как слуга, или, предположим, слуга похоронен вместо хозяина); invent what Wilkie Collins’ tragedy you like (придумайте любую трагедию в духе Уилки Коллинза, какая вам нравится; to invent – изобретать; invention – изобретение), and you still have not explained a candle without a candlestick, or why an elderly gentleman of good family should habitually spill snuff on the piano (и вы все равно не сможете объяснить, почему свеча – без подсвечника, или почему пожилой джентльмен из хорошей семьи имел привычку рассыпать нюхательный табак на пианино; habit – обыкновение; обычай; to spill – проливать/ся/; рассыпать/ся/). The core of the tale we could imagine (суть истории мы можем представить; core – центр; сердцевина; суть; to imagine – воображать, представлять себе); it is the fringes that are mysterious (но детали очень таинственные; fringe – бахрома; край; периферия). By no stretch of fancy can the human mind connect together snuff and diamonds and wax and loose clockwork (ни при каком напряжении фантазии человеческий разум не в состоянии объединить нюхательный табак и бриллианты, и воск, и разобранный часовой механизм; to stretch – тянуть/ся/; вытягивать/ся/; напрягать/ся/; to connect – соединять; связать; объединять).”

Suppose the servant really killed the master, or suppose the master isn’t really dead, or suppose the master is dressed up as the servant, or suppose the servant is buried for the master; invent what Wilkie Collins’ tragedy you like, and you still have not explained a candle without a candlestick, or why an elderly gentleman of good family should habitually spill snuff on the piano. The core of the tale we could imagine; it is the fringes that are mysterious. By no stretch of fancy can the human mind connect together snuff and diamonds and wax and loose clockwork.”

“I think I see the connection (мне кажется, я вижу связь),” said the priest. “This Glengyle was mad against the French Revolution (этот Гленгайл был страшно зол на французскую революцию; mad – сумасшедший, безумный; раздраженный; рассерженный, рассвирепевший). He was an enthusiast for the ancien regime (он был предан дореволюционному режиму; ancient /фр./ = ancient – дореволюционный режим /государственное устройство Франции до революции 1789 г./), and was trying to re-enact literally the family life of the last Bourbons (и пытался буквально восстановить в своей семье быт: «жизнь» последних Бурбонов; to re-enact – вновь узаконить; восстановить; воспроизводить). He had snuff because it was the eighteenth century luxury (у него был нюхательный табак, потому что в восемнадцатом веке это было роскошью; luxury – богатство; роскошь); wax candles, because they were the eighteenth century lighting (восковые свечи, потому что в восемнадцатом веке они /использовались в качестве/ освещения; lighting – освещение); the mechanical bits of iron represent the locksmith hobby of Louis XVI (механические детали из железа представляют слесарное хобби Людовика XVI; locksmith – слесарь, специалист по замкам; lock – замок; smith – кузнец); the diamonds are for the Diamond Necklace of Marie Antoinette (бриллианты /предназначались/ для /бриллиантового/ ожерелья Марии Антуанетты).”

“I think I see the connection,” said the priest. “This Glengyle was mad against the French Revolution. He was an enthusiast for the ancien regime, and was trying to re-enact literally the family life of the last Bourbons. He had snuff because it was the eighteenth century luxury; wax candles, because they were the eighteenth century lighting; the mechanical bits of iron represent the locksmith hobby of Louis XVI; the diamonds are for the Diamond Necklace of Marie Antoinette.”

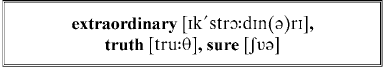

Both the other men were staring at him with round eyes (двое мужчин: «двое других мужчин» уставились на него круглыми глазами). “What a perfectly extraordinary notion (какая исключительно экстраординарная точка зрения)!” cried Flambeau. “Do you really think that is the truth (вы действительно думаете, что так оно и есть; truth – правда)?”

“I am perfectly sure it isn’t (я абсолютно уверен, что это не так; perfectly – совершенно; полностью),” answered Father Brown, “only you said that nobody could connect snuff and diamonds and clockwork and candles (только вы сказали, что никто не сможет установить логическую связь между табаком, бриллиантами, часовым механизмом и свечами). I give you that connection off-hand (я экспромтом установил: «даю» эту смысловую связь; off-hand – без подготовки; экспромтом). The real truth, I am very sure, lies deeper (но /истинная/ правда, я уверен, лежит глубже; deep – глубокий).”

Both the other men were staring at him with round eyes. “What a perfectly extraordinary notion!” cried Flambeau. “Do you really think that is the truth?”

“I am perfectly sure it isn’t,” answered Father Brown, “only you said that nobody could connect snuff and diamonds and clockwork and candles. I give you that connection off-hand. The real truth, I am very sure, lies deeper.”

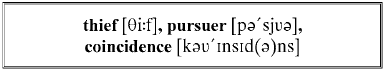

He paused a moment and listened to the wailing of the wind in the turrets (он замолчал на минуту и прислушался к завыванию ветра в башенках /замка/; to wail – причитать, стенать; оплакивать; turret – башенка). Then he said (затем он сказал), “The late Earl of Glengyle was a thief (покойный граф Гленгайл был вором). He lived a second and darker life as a desperate housebreaker (он вел двойной образ жизни: «он жил второй и более темной жизнью» и был отчаянным грабителем; housebreaker – взломщик; грабитель; house – дом; to break – ломать). He did not have any candlesticks because he only used these candles cut short in the little lantern he carried (у него не было никаких подсвечников, потому что он только использовал эти обрезанные свечи в маленьком фонарике, который он носил с собой = брал на дело). The snuff he employed as the fiercest French criminals have used pepper (табак он использовал, как самые жестокие преступники-французы использовали перец): to fling it suddenly in dense masses in the face of a captor or pursuer (бросить неожиданно большое количество в лицо тюремщика или преследователя; captor – тюремщик; pursuer – преследователь; to pursue – преследовать). But the final proof is in the curious coincidence of the diamonds and the small steel wheels (но заключительное доказательство в странном сочетании бриллиантов и маленьких стальных колесиков; to coincide – совпадать; соответствовать). Surely that makes everything plain to you (без сомнения, это все объясняет вам; plain – очевидный; явный)? Diamonds and small steel wheels are the only two instruments with which you can cut out a pane of glass (ведь только при помощи алмазов/бриллиантов и маленьких стальных колесиков можно вырезать оконное стекло; pane of glass – оконное стекло).”

He paused a moment and listened to the wailing of the wind in the turrets. Then he said, “The late Earl of Glengyle was a thief. He lived a second and darker life as a desperate housebreaker. He did not have any candlesticks because he only used these candles cut short in the little lantern he carried. The snuff he employed as the fiercest French criminals have used pepper: to fling it suddenly in dense masses in the face of a captor or pursuer. But the final proof is in the curious coincidence of the diamonds and the small steel wheels. Surely that makes everything plain to you? Diamonds and small steel wheels are the only two instruments with which you can cut out a pane of glass.”

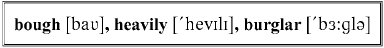

The bough of a broken pine tree lashed heavily in the blast against the windowpane behind them, as if in parody of a burglar (сук сломанной сосны сильно ударился из-за порыва ветра по оконному стеклу /за ними/, как будто это была пародия на вора-домушника; to break; to lash – хлестать; сильно ударять; burglar – вор-домушник), but they did not turn round (но никто не повернулся /на этот звук/). Their eyes were fastened on Father Brown (все глаза были прикованы к отцу Брауну; to fasten – прикреплять; устремлять, сосредоточивать /взгляд, внимание/).

“Diamonds and small wheels (бриллианты и колесики),” repeated Craven ruminating (повторил Крейвен задумчиво; to ruminate – жевать жвачку; раздумывать, размышлять). “Is that all that makes you think it the true explanation (это все, что позволяет вам думать, что вы нашли истинное объяснение; true – верный; правильный; to explain – пояснять)?”

The bough of a broken pine tree lashed heavily in the blast against the windowpane behind them, as if in parody of a burglar, but they did not turn round. Their eyes were fastened on Father Brown.

“Diamonds and small wheels,” repeated Craven ruminating. “Is that all that makes you think it the true explanation?”

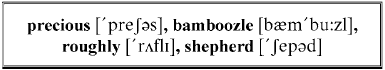

“I don’t think it the true explanation (я не думаю, что это истинное объяснение),” replied the priest placidly (ответил священник мягко; placid – безмятежный, мирный, спокойный, тихий); “but you said that nobody could connect the four things (но вы сказали, что никто не может объединить эти четыре предмета). The true tale, of course, is something much more humdrum (на самом деле: «правдивый рассказ», конечно, все гораздо банальнее; humdrum – однообразие; повседневность; банальный). Glengyle had found, or thought he had found, precious stones on his estate (Гленгайл нашел, или думал, что нашел, драгоценные камни на своем участке; estate – поместье; имение). Somebody had bamboozled him with those loose brilliants, saying they were found in the castle caverns (кто-то его разыграл с этими бриллиантами /россыпью/, сказав, что они были найдены в пещерах замка = под замком; to bamboozle – обманывать; мистифицировать; cavern – пещера; полость). The little wheels are some diamond-cutting affair (маленькие колесики /связаны с/ обработкой алмазов; affair – дело). He had to do the thing very roughly and in a small way (ему нужно было все делать начерно и потихоньку; roughly – грубо; небрежно; in a small way – в небольшом масштабе; понемногу, потихоньку), with the help of a few shepherds or rude fellows on these hills (при помощи нескольких пастухов или неотесанных молодцов из этой местности: «с этих холмов»; shepherd – пастух; rude – грубый; невежественный). Snuff is the one great luxury of such Scotch shepherds (табак – это единственная роскошь для /таких/ шотландских пастухов); it’s the one thing with which you can bribe them (это единственная вещь, с помощью которой их можно подкупить; to bribe – подкупать). They didn’t have candlesticks because they didn’t want them (у них не было подсвечников, потому что они были им не нужны); they held the candles in their hands when they explored the caves (когда они исследовали пещеры, они держали свечи в руках; to hold; to explore – исследовать).”

“I don’t think it the true explanation,” replied the priest placidly; “but you said that nobody could connect the four things. The true tale, of course, is something much more humdrum. Glengyle had found, or thought he had found, precious stones on his estate. Somebody had bamboozled him with those loose brilliants, saying they were found in the castle caverns. The little wheels are some diamond-cutting affair. He had to do the thing very roughly and in a small way, with the help of a few shepherds or rude fellows on these hills. Snuff is the one great luxury of such Scotch shepherds; it’s the one thing with which you can bribe them. They didn’t have candlesticks because they didn’t want them; they held the candles in their hands when they explored the caves.”

“Is that all (это все)?” asked Flambeau after a long pause (спросил Фламбо после продолжительной паузы). “Have we got to the dull truth at last (это и есть скучная правда наконец: «мы добрались, наконец, до скучной правды»; to get to smth. – добраться до чего-л.)?”

“Oh, no (о, нет),” said Father Brown.

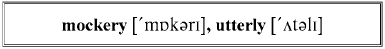

As the wind died in the most distant pine woods with a long hoot as of mockery (словно насмехаясь над ними, ветер протяжно взвыл и затих: «умер» в самом дальнем сосновом лесу; hoot – гиканье; крики; mockery – насмешка) Father Brown, with an utterly impassive face, went on (а отец Браун продолжил с совершенно бесстрастным лицом; impassive – невозмутимый, бесстрастный; to go on):

“Is that all?” asked Flambeau after a long pause. “Have we got to the dull truth at last?”

“Oh, no,” said Father Brown.

As the wind died in the most distant pine woods with a long hoot as of mockery Father Brown, with an utterly impassive face, went on:

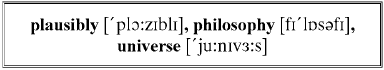

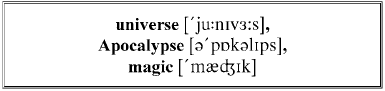

“I only suggested that because you said one could not plausibly connect snuff with clockwork or candles with bright stones (я только предположил это, потому что вы сказали, что невозможно правдоподобно связать табак с часовым механизмом или свечи с бриллиантами: «блестящими драгоценными камнями»; to suggest – предлагать; выдвигать в качестве предположения; to say; plausibly – правдоподобно). Ten false philosophies will fit the universe (десять ложных доктрин подойдут для вселенной; to fit – подходить; соответствовать); ten false theories will fit Glengyle Castle (десять ложных теорий подойдут /к тайне/ замка Гленгайл). But we want the real explanation of the castle and the universe (но нам нужно истинное объяснение по поводу замка и вселенной; real – реальный; подлинный; истинный). But are there no other exhibits (а нет ли других вещественных доказательств; exhibit – экспонат; вещественное доказательство)?”

Craven laughed, and Flambeau rose smiling to his feet and strolled down the long table (Крейвен засмеялся, Фламбо улыбнулся, встал и пошел вдоль длинного стола; to rise – подниматься, вставать; to stroll – прогуливаться /медленно/).

“I only suggested that because you said one could not plausibly connect snuff with clockwork or candles with bright stones. Ten false philosophies will fit the universe; ten false theories will fit Glengyle Castle. But we want the real explanation of the castle and the universe. But are there no other exhibits?”

Craven laughed, and Flambeau rose smiling to his feet and strolled down the long table.

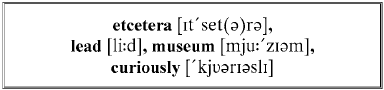

“Items five, six, seven, etc. (пункты пять, шесть, семь и так далее; etc. – сокр. от etcetera /лат./),” he said, “and certainly more varied than instructive (безусловно, более разнообразны, но менее информативны). A curious collection, not of lead pencils, but of the lead out of lead pencils (любопытная коллекция, но не графитовых карандашей, а грифелей из графитовых карандашей; curious – любопытный; lead pencil – графитовый карандаш; lead – свинец; графит для карандашей; грифель). A senseless stick of bamboo, with the top rather splintered (/бессмысленная/ бамбуковая палка, с сильно расщепленным верхним концом; sense – чувство; разум; смысл). It might be the instrument of the crime (может быть, это орудие преступления; instrument – орудие; crime – преступление). Only, there isn’t any crime (только, нет преступления). The only other things are a few old missals and little Catholic pictures (из других вещей – несколько старинных служебников и католические миниатюры; missal – служебник; picture – картина; рисунок; изображение), which the Ogilvies kept, I suppose, from the Middle Ages (которые Оджилви хранили, как я думаю, со средних веков; to keep – держать; хранить; беречь; to suppose – предполагать) – their family pride being stronger than their Puritanism (их фамильная гордость была сильнее, чем их пуританизм). We only put them in the museum because they seem curiously cut about and defaced (мы только приобщили эти вещи к делу: «поместили их в музей» лишь потому, что они как-то странно разрезаны и попорчены; to cut – резать; to deface – портить; повреждать).”

“Items five, six, seven, etc.,” he said, “and certainly more varied than instructive. A curious collection, not of lead pencils, but of the lead out of lead pencils. A senseless stick of bamboo, with the top rather splintered. It might be the instrument of the crime. Only, there isn’t any crime. The only other things are a few old missals and little Catholic pictures, which the Ogilvies kept, I suppose, from the Middle Ages – their family pride being stronger than their Puritanism. We only put them in the museum because they seem curiously cut about and defaced.”

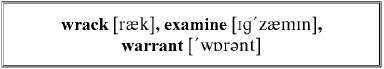

The heady tempest without drove a dreadful wrack of clouds across Glengyle and threw the long room into darkness (снаружи неистовая буря пригнала к замку Гленгайл грозные штормовые тучи, и в длинной комнате стало темно; tempest – буря; without – без; в отсутствие; снаружи; to drive – гнать; wrack – остатки кораблекрушения; to throw – бросать) as Father Brown picked up the little illuminated pages to examine them (когда отец Браун взял /слегка освещенные/ странички, чтобы изучить их; to examine – рассматривать; изучать). He spoke before the drift of darkness had passed (он заговорил до того, как прошли тучи; drift – медленное течение/перемещение; дрейф; движение облака дыма; darkness – темнота); but it was the voice of an utterly new man (но это был голос совершенно другого человека; utterly – весьма; очень; совершенно).

“Mr. Craven,” said he, talking like a man ten years younger (сказал он, говоря как человек, помолодевший на десять лет), “you have got a legal warrant, haven’t you, to go up and examine that grave (вы ведь имеете законный ордер, не правда ли, чтобы пойти и осмотреть /ту/ могилу)? The sooner we do it the better, and get to the bottom of this horrible affair (чем раньше мы сделаем это – тем лучше, и мы разгадаем это страшное дело; to get to the bottom of smth. – тщательно изучить; докопаться до сути чего-л.: «добраться до дна»; bottom – низ; дно). If I were you I should start now (на вашем месте: «если бы я был вы» я бы отправился /прямо/ сейчас).”

“Now (сейчас),” repeated the astonished detective (повторил удивленный сыщик), “and why now (почему сейчас)?”

The heady tempest without drove a dreadful wrack of clouds across Glengyle and threw the long room into darkness as Father Brown picked up the little illuminated pages to examine them. He spoke before the drift of darkness had passed; but it was the voice of an utterly new man.

“Mr. Craven,” said he, talking like a man ten years younger, “you have got a legal warrant, haven’t you, to go up and examine that grave? The sooner we do it the better, and get to the bottom of this horrible affair. If I were you I should start now.”

“Now,” repeated the astonished detective, “and why now?”

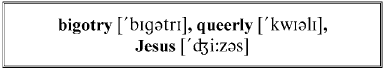

“Because this is serious (потому что /все/ это серьезно),” answered Brown; “this is not spilt snuff or loose pebbles, that might be there for a hundred reasons (это не рассыпанный табак или россыпь горного хрусталя, которые могут быть здесь по сотне причин; to spill – проливать; рассыпать; pebble – галька; гравий; горный хрусталь). There is only one reason I know of for this being done (я знаю только одну причину, по которой это было сделано); and the reason goes down to the roots of the world (а причина уходит к корням мира = причина восходит к истокам вселенной; to go down – сойти вниз; опускаться; world – мир; свет; вселенная). These religious pictures are not just dirtied or torn or scrawled over (эти религиозные картины не просто запачканы или порваны или исчерканы; dirt – грязь; dirty – грязный; to dirty – пачкать; to tear – рвать; разрывать; to scrawl – писать наспех; писать неразборчиво; писать каракулями, закорючками), which might be done in idleness or bigotry, by children or by Protestants (что могло бы быть сделано в безделье или /в порыве/ фанатизма детьми или протестантами; to idle – лениться; бездельничать; idle – праздный). These have been treated very carefully – and very queerly (с ними /этими вещами/ обошлись очень аккуратно – и очень странно). In every place where the great ornamented name of God comes in the old illuminations it has been elaborately taken out (в каждом случае, когда великолепно расписанное имя Бога встречается украшенным золотом и серебром, эти драгоценные металлы искусным образом вынуты; illumination – освещение; вдохновение; украшение яркими красками, золотом и серебром; to take out – вынимать; удалять). The only other thing that has been removed is the halo round the head of the Child Jesus (единственно, что было также удалено, это сияние над головой Иисуса Христа). Therefore, I say, let us get our warrant and our spade and our hatchet, and go up and break open that coffin (поэтому, послушайте, давайте возьмем наш ордер, /нашу/ лопату и /наш/ топорик и пойдем вскроем гроб; therefore – по этой причине; вследствие этого; поэтому).”

“Because this is serious,” answered Brown; “this is not spilt snuff or loose pebbles, that might be there for a hundred reasons. There is only one reason I know of for this being done; and the reason goes down to the roots of the world. These religious pictures are not just dirtied or torn or scrawled over, which might be done in idleness or bigotry, by children or by Protestants. These have been treated very carefully – and very queerly. In every place where the great ornamented name of God comes in the old illuminations it has been elaborately taken out. The only other thing that has been removed is the halo round the head of the Child Jesus. Therefore, I say, let us get our warrant and our spade and our hatchet, and go up and break open that coffin.”

“What do you mean (что вы хотите сказать; to mean – намереваться; иметь в виду; означать)?” demanded the London officer (требовательно спросил инспектор из Лондона; to demand – требовать).

“I mean (я хочу сказать),” answered the little priest, and his voice seemed to rise slightly in the roar of the gale (ответил маленький священник, и показалось, что он слегка повысил голос, /чтобы перекрыть/ рев бури; gale – шторм; буря). “I mean that the great devil of the universe may be sitting on the top tower of this castle at this moment (я хочу сказать, что, возможно, сам Сатана: «великий дьявол вселенной» сидит сейчас на башне замка; top – верхушка, вершина), as big as a hundred elephants (огромный, как сто слонов), and roaring like the Apocalypse (и раздается рев: «ревет», как в Апокалипсисе). There is black magic somewhere at the bottom of this (в основе /всего этого/ лежит черная магия).”

“What do you mean?” demanded the London officer.

“I mean,” answered the little priest, and his voice seemed to rise slightly in the roar of the gale. “I mean that the great devil of the universe may be sitting on the top tower of this castle at this moment, as big as a hundred elephants, and roaring like the Apocalypse. There is black magic somewhere at the bottom of this.”

“Black magic (черная магия),” repeated Flambeau in a low voice, for he was too enlightened a man not to know of such things (тихо повторил Фламбо, /ибо/ он был слишком образованным человеком, чтобы не знать о таких вещах; to enlighten – просвещать; обучать); “but what can these other things mean (но что же тогда могут означать эти остальные вещи)?”

“Oh, something damnable, I suppose (что-нибудь мерзкое, я думаю; damnable – заслуживающий осуждения, порицания; проклятый, треклятый, чертовский, отвратительный; to damn – проклинать; осуждать),” replied Brown impatiently (ответил /отец/ Браун нетерпеливо). “How should I know (откуда мне знать)? How can I guess all their mazes down below (как я могу разгадать этот запутанный лабиринт; maze – лабиринт; путаница; сложный комплекс проблем; down below – в могиле; в преисподней)? Perhaps you can make a torture out of snuff and bamboo (возможно, можно пытать при помощи табака и бамбука = может быть, табак и бамбук используются для пыток; torture – пытка). Perhaps lunatics lust after wax and steel filings (возможно, сумасшедшие без ума от воска и стальной стружки; to lust – сильно желать; жаждать; steel – сталь; filing – стружка; file – напильник; to file – шлифовать, затачивать напильником). Perhaps there is a maddening drug made of lead pencils (возможно, из графитовых карандашей делают наркотик, лишающий людей рассудка; to madden – сводить с ума; лишить рассудка; mad – сумасшедший, безумный; drug – медикамент; лекарство; наркотик)! Our shortest cut to the mystery is up the hill to the grave (наш кратчайший путь к /решению/ тайны – наверху холма у могилы; cut – разрезание; уменьшение; кратчайший путь; to cut – резать, срезать).”

“Black magic,” repeated Flambeau in a low voice, for he was too enlightened a man not to know of such things; “but what can these other things mean?”

“Oh, something damnable, I suppose,” replied Brown impatiently. “How should I know? How can I guess all their mazes down below? Perhaps you can make a torture out of snuff and bamboo. Perhaps lunatics lust after wax and steel filings. Perhaps there is a maddening drug made of lead pencils! Our shortest cut to the mystery is up the hill to the grave.”

His comrades hardly knew that they had obeyed and followed him till a blast of the night wind nearly flung them on their faces in the garden (его собеседники навряд ли осознавали, что они послушались его и последовали за ним, пока порыв ночного ветра не ударил им в лицо в саду; comrade – товарищ; друг; компаньон; to know; to fling – бросать/ся/; кидать/ся/). Nevertheless they had obeyed him like automata (однако слушались они его как автоматы; automaton – автомат; autimata – мн. ч.); for Craven found a hatchet in his hand, and the warrant in his pocket (поскольку у Крейвена оказался топорик в руке, а ордер – в кармане); Flambeau was carrying the heavy spade of the strange gardener (Фламбо нес тяжелую лопату странного садовника); Father Brown was carrying the little gilt book from which had been torn the name of God (отец Браун нес маленькую позолоченную книгу, из которой было вынуто: «вырвано» имя Божье; to gild – украшать; золотить; to tear – рвать).

His comrades hardly knew that they had obeyed and followed him till a blast of the night wind nearly flung them on their faces in the garden. Nevertheless they had obeyed him like automata; for Craven found a hatchet in his hand, and the warrant in his pocket; Flambeau was carrying the heavy spade of the strange gardener; Father Brown was carrying the little gilt book from which had been torn the name of God.

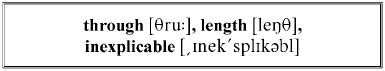

The path up the hill to the churchyard was crooked but short (тропинка, которая вела на холм к кладбищу, была извилистой, но короткой; churchyard – кладбище; погост; church – церковь; yard – ярд; брус; внутренний двор; to crook – сгибать, искривлять); only under that stress of wind it seemed laborious and long (но при таком сильном ветре она казалась утомительной и длинной; labour – труд; работа). Far as the eye could see, farther and farther as they mounted the slope (насколько хватало глаз, все дальше и дальше, как они взбирались наверх; far – далекий; farther – дальше; slope – наклон; склон), were seas beyond seas of pines, now all aslope one way under the wind (были моря сосен: «море за морем сосен», клонившиеся в одну сторону из-за ветра; beyond – далеко, вдали; на расстоянии; aslope – косо; покато). And that universal gesture seemed as vain as it was vast (и это всеобщее движение /ветра/ казалось столь же тщетным, насколько оно был безбрежным; universal – универсальный; всемирный; всеобщий; gesture – жест; действие), as vain as if that wind were whistling about some unpeopled and purposeless planet (столь же тщетным, как будто тот ветер насвистывал о некоторой безлюдной и бесцельной планете; to whistle – свистеть; purpose – назначение; цель). Through all that infinite growth of grey-blue forests sang, shrill and high, that ancient sorrow (и на этом фоне: «через все это» бесконечного увеличения серо-синих лесов звучала: «пела», пронзительно и высоко, та древняя печаль; through – через; сквозь; infinite – бесконечный; to grow – расти; увеличиваться; to sing; ancient – древний) that is in the heart of all heathen things (что находится в сердце всех языческих созданий). One could fancy that the voices from the under world of unfathomable foliage were cries of the lost and wandering pagan gods (можно было предположить, что голоса, /раздававшиеся/ из-под мира бездонной листвы, были криками потерянных и блуждающих языческих богов; to fancy – очень хотеть; представлять; воображать; unfathomable – неизмеримый; бездонный; fathom – фатом, фадом, морская сажень /английская единица длины; = 6 футам = 182 см/; foliage – листва; листья; to wander – странствовать; скитаться; pagan – языческий): gods who had gone roaming in that irrational forest, and who will never find their way back to heaven (богов, которые ушли бродить в тот иррациональный лес и которые никогда не найдут путь назад к небесам).

The path up the hill to the churchyard was crooked but short; only under that stress of wind it seemed laborious and long. Far as the eye could see, farther and farther as they mounted the slope, were seas beyond seas of pines, now all aslope one way under the wind. And that universal gesture seemed as vain as it was vast, as vain as if that wind were whistling about some unpeopled and purposeless planet. Through all that infinite growth of grey-blue forests sang, shrill and high, that ancient sorrow that is in the heart of all heathen things. One could fancy that the voices from the under world of unfathomable foliage were cries of the lost and wandering pagan gods: gods who had gone roaming in that irrational forest, and who will never find their way back to heaven.

“You see (понимаете; to see – видеть; смотреть; представить себе; считать; полагать),” said Father Brown in low but easy tone (тихо, но спокойно сказал отец Браун; low – низкий; тихий), “Scotch people before Scotland existed were a curious lot (шотландцы до существования Шотландии были любопытными/странными людьми; curious – любопытный; любознательный; возбуждающий любопытство; чудной, необычный; lot – доля; судьба; группа /людей/). In fact, they’re a curious lot still (собственно, они и сейчас странные). But in the prehistoric times I fancy they really worshipped demons (но в доисторические времена они, я думаю, действительно поклонялись бесам; to fancy – очень хотеть; воображать; думать; to worship – поклоняться; почитать). That (вот),” he added genially (он добавил добродушно), “is why they jumped at the Puritan theology (поэтому они так быстро приняли: «прыгнули в» пуританскую теологию).”

“You see,” said Father Brown in low but easy tone, “Scotch people before Scotland existed were a curious lot. In fact, they’re a curious lot still. But in the prehistoric times I fancy they really worshipped demons. That,” he added genially, “is why they jumped at the Puritan theology.”

“My friend (друг мой),” said Flambeau, turning in a kind of fury (сказал Фламбо, оборачиваясь к нему с некоторым раздражением: «с чем-то вроде ярости»; kind – вид, разновидность), “what does all that snuff mean (ну и что же тогда означает этот нюхательный табак)?”

“My friend,” replied Brown, with equal seriousness (ответил /отец/ Браун так же серьезно: «с неизменной серьезностью»; equal – равный, одинаковый; тождественный), “there is one mark of all genuine religions: materialism (у всех истинных религий есть одна /общая/ черта: материализм; genuine – истинный, подлинный, неподдельный). Now, devil-worship is a perfectly genuine religion (вот, а культ сатаны – истинная религия в полной мере).”

“My friend,” said Flambeau, turning in a kind of fury, “what does all that snuff mean?”

“My friend,” replied Brown, with equal seriousness, “there is one mark of all genuine religions: materialism. Now, devil-worship is a perfectly genuine religion.”

They had come up on the grassy scalp of the hill (они взобрались на вершину холма, покрытую травой; scalp – скальп; оголенная вершина горы), one of the few bald spots that stood clear of the crashing and roaring pine forest (одно из немногих мест без растительности, свободное от грохочущего и ревущего соснового леса; to crash – грохотать; to roar – реветь; pine – сосна). A mean enclosure, partly timber and partly wire, rattled in the tempest to tell them the border of the graveyard (невзрачная изгородь из проволоки и деревянных столбиков: «частично балки и частично проволока» дребезжала /на фоне/ бури, сообщая путникам: «им», где находится граница кладбища; enclosure – ограда, забор; timber – лесоматериалы; изгородь; балка; border – граница). But by the time Inspector Craven had come to the corner of the grave (но к тому моменту, когда инспектор Крейвен подошел к углу могилы), and Flambeau had planted his spade point downwards and leaned on it (а Фламбо воткнул лопату /в землю/ и оперся на нее; point – острие), they were both almost as shaken as the shaky wood and wire (их обоих уже так сотрясало /от порывов ветра/, как лес и проволоку; to shake – трясти). At the foot of the grave grew great tall thistles, grey and silver in their decay (на краю могилы: «у основания могилы» росли большие высокие отцветающие серо-серебристые репейники; foot – ступня; фут; подножие; нижний край; to grow; decay – гниение; разложение; увядание). Once or twice, when a ball of thistledown broke under the breeze and flew past him (один или два раза, когда порыв ветра отрывал колючий шарик репейника и он летел мимо него; to break; to fly), Craven jumped slightly as if it had been an arrow (Крейвен слегка подпрыгивал, как будто это была стрела).

They had come up on the grassy scalp of the hill, one of the few bald spots that stood clear of the crashing and roaring pine forest. A mean enclosure, partly timber and partly wire, rattled in the tempest to tell them the border of the graveyard. But by the time Inspector Craven had come to the corner of the grave, and Flambeau had planted his spade point downwards and leaned on it, they were both almost as shaken as the shaky wood and wire. At the foot of the grave grew great tall thistles, grey and silver in their decay. Once or twice, when a ball of thistledown broke under the breeze and flew past him, Craven jumped slightly as if it had been an arrow.

Flambeau drove the blade of his spade through the whistling grass into the wet clay below (Фламбо вонзил лопату в свистящую траву и дальше в мокрую глину: «в мокрую глину под /ней/»; to drive; blade – клинок; острие; clay – глина). Then he seemed to stop and lean on it as on a staff (затем он вроде как остановился и облокотился /на лопату/, как на посох; to seem – казаться; staff – палка; посох).

“Go on (продолжайте),” said the priest very gently (сказал священник очень мягко). “We are only trying to find the truth (мы только хотим выяснить правду). What are you afraid of (чего вы боитесь)?”

“I am afraid of finding it (я боюсь обнаружить ее),” said Flambeau.

Flambeau drove the blade of his spade through the whistling grass into the wet clay below. Then he seemed to stop and lean on it as on a staff.

“Go on,” said the priest very gently. “We are only trying to find the truth. What are you afraid of?”

“I am afraid of finding it,” said Flambeau.

The London detective spoke suddenly in a high crowing voice that was meant to be conversational and cheery (сыщик из Лондона вдруг заговорил высоким каркающим голосом, который должен был казаться беспечным: «разговорным» и бодрым; to mean – предназначать; conversation – разговор; беседа). “I wonder why he really did hide himself like that (интересно, а почему он так прятался на самом деле). Something nasty, I suppose; was he a leper (что-нибудь ужасное, я думаю; /может быть/ он был прокаженным; to suppose – предполагать; полагать; думать; leper – прокаженный; leprosy – проказа)?”

“Something worse than that (что-нибудь хуже, чем это),” said Flambeau.

“And what do you imagine (а что вы можете представить; to imagine – воображать),” asked the other (спросил сыщик: «другой»), “would be worse than a leper (хуже, чем быть прокаженным)?”

“I don’t imagine it (я не могу себе это представить),” said Flambeau.

The London detective spoke suddenly in a high crowing voice that was meant to be conversational and cheery. “I wonder why he really did hide himself like that. Something nasty, I suppose; was he a leper?”

“Something worse than that,” said Flambeau.

“And what do you imagine,” asked the other, “would be worse than a leper?”

“I don’t imagine it,” said Flambeau.

He dug for some dreadful minutes in silence, and then said in a choked voice (несколько ужасных минут он копал в тишине, а затем сказал напряженным голосом; to dig; to choke – душить; задыхаться), “I’m afraid of his not being the right shape (я боюсь, что он будет неправильной формы = что с ним что-то будет не так).”

“Nor was that piece of paper, you know (тоже было и с тем листом бумаги, как вы знаете),” said Father Brown quietly (сказал отец Браун тихо), “and we survived even that piece of paper (а мы пережили даже тот лист бумаги; to survive – пережить; выдержать; перенести).”

He dug for some dreadful minutes in silence, and then said in a choked voice “I’m afraid of his not being the right shape.”

“Nor was that piece of paper, you know,” said Father Brown quietly, “and we survived even that piece of paper.”

Flambeau dug on with a blind energy (Фламбо продолжал энергично копать: «копать со слепой энергией»). But the tempest had shouldered away the choking grey clouds that clung to the hills like smoke (но ветер унес: «буря унесла» тяжелые серые облака, которые удерживались над холмами, подобно дыму; to cling – цепляться; прилипать; крепко держаться) and revealed grey fields of faint starlight (и показались: «буря обнаружила/показала» серые поля, /освещенные/ слабым звездным светом; starlight – свет звезд) before he cleared the shape of a rude timber coffin, and somehow tipped it up upon the turf (до того как он /Фламбо/ очистил гроб из грубой древесины /от земли/ и кое-как поставил его на дерн; to clear – очищать; shape – форма; очертание; coffin – гроб; to tip – опрокидывать; сваливать). Craven stepped forward with his axe (Крейвен сделал шаг вперед с топором); a thistle-top touched him, and he flinched (верхушка чертополоха коснулась его, и он вздрогнул; to flinch – вздрагивать /от боли, испуга/; передернуться /от отвращения/). Then he took a firmer stride (тогда он встал поустойчивее: «сделал более твердый шаг»; stride – большой шаг), and hacked and wrenched with an energy like Flambeau’s till the lid was torn off (и начал наносить удары: «ломал и выворачивал» с энергией Фламбо, пока крышка не была сорвана; to tear – рвать; to tear off – срывать), and all that was there lay glimmering in the grey starlight (и все, что там было /внутри/, лежало, тускло мерцая в сером звездном свете; to lie).

Flambeau dug on with a blind energy. But the tempest had shouldered away the choking grey clouds that clung to the hills like smoke and revealed grey fields of faint starlight before he cleared the shape of a rude timber coffin, and somehow tipped it up upon the turf. Craven stepped forward with his axe; a thistle-top touched him, and he flinched. Then he took a firmer stride, and hacked and wrenched with an energy like Flambeau’s till the lid was torn off, and all that was there lay glimmering in the grey starlight.

“Bones (кости),” said Craven; and then he added (сказал Крейвен и затем добавил), “but it is a man (но это человек),” as if that were something unexpected (как будто это было что-то неожиданное; to expect – ожидать).

“Is he (у него),” asked Flambeau in a voice that went oddly up and down (спросил Фламбо со странной восходяще-нисходящей интонацией: «голосом, который странно поднялся и опустился»; up and down – вверх и вниз), “is he all right (у него все в порядке)?”

“Seems so (кажется, да),” said the officer huskily, bending over the obscure and decaying skeleton in the box (сказал сыщик нервно, наклоняясь над неясным и гниющим скелетом в ящике; husky – охрипший /от волнения и т. п./, сиплый; to bend over smth. – наклоняться над чем-л.). “Wait a minute (подождите минуту).”

“Bones,” said Craven; and then he added, “but it is a man,” as if that were something unexpected.

“Is he,” asked Flambeau in a voice that went oddly up and down, “is he all right?”

“Seems so,” said the officer huskily, bending over the obscure and decaying skeleton in the box. “Wait a minute.”

A vast heave went over Flambeau’s huge figure (Фламбо почувствовал приступ тошноты: «на огромное тело Фламбо накатила тошнота»; vast – обширный; громадный; большой; heave – подъем; поднимание; глубокий вдох; дыхание; рвотный рефлекс). “And now I come to think of it (мне думается: «теперь, когда я думаю об этом»),” he cried, “why in the name of madness shouldn’t he be all right (/во имя безумия/ почему с ним должно быть что-то не так; in the name of – именем; на имя; в лице; во имя)? What is it gets hold of a man on these cursed cold mountains (что овладевает человеком в этих проклятых холодных горах; to curse – сквернословить; ругаться; проклинать)? I think it’s the black, brainless repetition; all these forests, and over all an ancient horror of unconsciousness (я думаю /во всем виновата/ черная безмозглая повторяемость; все эти леса, а над всем этим древний ужас перед бессознательным состоянием; brain – мозг; consciousness – сознание; понимание; сознательность; разум). It’s like the dream of an atheist (это как сон атеиста; dream – сон; сновидение; мечта). Pine-trees and more pine-trees and millions more pine-trees (сосны, и снова сосны, и еще миллионы сосен) – ”

“God (Господи)!” cried the man by the coffin (закричал человек у гроба), “but he hasn’t got a head (но у него нет головы).”

A vast heave went over Flambeau’s huge figure. “And now I come to think of it,” he cried, “why in the name of madness shouldn’t he be all right? What is it gets hold of a man on these cursed cold mountains? I think it’s the black, brainless repetition; all these forests, and over all an ancient horror of unconsciousness. It’s like the dream of an atheist. Pine-trees and more pine-trees and millions more pine-trees – ”

“God!” cried the man by the coffin, “but he hasn’t got a head.”