6

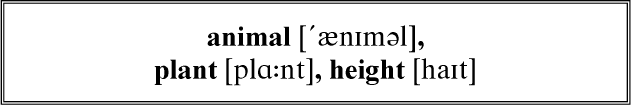

The people of Lilliput are just under six inches tall (жители Лилипутии ростом немного ниже шести дюймов). All animals, plants and trees are in exact proportion (все животные, растения и деревья точно соразмерны /этой величине/; proportion – пропорция; /правильное/ соотношение; соразмерность, пропорциональность). For instance, the tallest horses and cows are between four and five inches in height (например, самые высокие = крупные лошади и коровы имеют от четырех до пяти дюймов в вышину; between – между). The sheep are about an inch and a half tall (овцы – около полутора дюймов). The largest birds are about the size of small ones in our part of the world (самые большие птицы имеют размеры маленьких = как маленькие в нашей части света) and the smallest are almost impossible to see (а самых мелких почти невозможно увидеть).

The people of Lilliput are just under six inches tall. All animals, plants and trees are in exact proportion. For instance, the tallest horses and cows are between four and five inches in height. The sheep are about an inch and a half tall. The largest birds are about the size of small ones in our part of the world and the smallest are almost impossible to see.

The people of Lilliput are just under six inches tall. All animals, plants and trees are in exact proportion. For instance, the tallest horses and cows are between four and five inches in height. The sheep are about an inch and a half tall. The largest birds are about the size of small ones in our part of the world and the smallest are almost impossible to see.

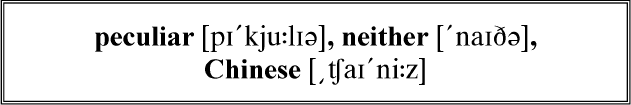

The people are well educated (люди хорошо образованы), but their manner of writing is very peculiar (но их манера письма очень своеобразна/необычна). It is neither from left to right like the Europeans (они пишут не /так/ как европейцы – слева направо: «она не слева направо, как /у/…»), nor right to left like the Arabs (и не /так/ как арабы – справа налево; neither… nor… – ни… ни…; не…, также не…; не… и не…). Nor is it from top to bottom like the Chinese (и не /так/ как китайцы – сверху вниз). It is from one corner of the paper to the other, like ladies in England (/но/ как английские дамы – от одного угла страницы к другому; paper – бумага; лист бумаги).

The people are well educated, but their manner of writing is very peculiar. It is neither from left to right like the Europeans, nor right to left like the Arabs. Nor is it from top to bottom like the Chinese. It is from one corner of the paper to the other, like ladies in England.

The people are well educated, but their manner of writing is very peculiar. It is neither from left to right like the Europeans, nor right to left like the Arabs. Nor is it from top to bottom like the Chinese. It is from one corner of the paper to the other, like ladies in England.

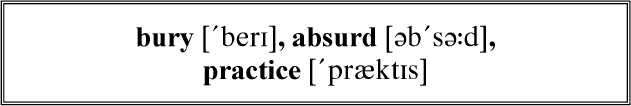

They bury their dead head downwards (они хоронят умерших /кладя тело/ головою вниз). They believe that in a thousand years time the dead will rise again (они верят, что через тысячу лет мертвые воскреснут; to rise – восходить, вставать, подниматься; воскресать). During this time the earth (за это время земля) – which they believe is flat (которую они считают плоской) – will turn upside down (перевернется вверх дном: «верхом вниз»; upside – верхняя сторона, верхняя часть). So when the dead rise again (поэтому, когда мертвые воскреснут), they will be standing on their feet (они окажутся стоящими /прямо/ на ногах). The most educated people agree that this idea is absurd (наиболее образованные люди признают, что это представление = верование нелепо), but the practice still continues (но обычай сохраняется до сих пор; to continue – продолжать/ся/).

They bury their dead head downwards. They believe that in a thousand years time the dead will rise again. During this time the earth (which they believe is flat) will turn upside down. So when the dead rise again, they will be standing on their feet. The most educated people agree that this idea is absurd, but the practice still continues.

They bury their dead head downwards. They believe that in a thousand years time the dead will rise again. During this time the earth (which they believe is flat) will turn upside down. So when the dead rise again, they will be standing on their feet. The most educated people agree that this idea is absurd, but the practice still continues.

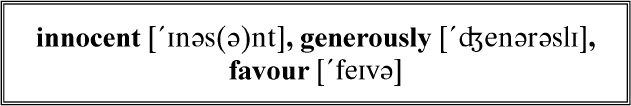

There are some very peculiar laws and customs in this Empire (в этой империи существуют некоторые весьма своеобразные законы и обычаи). It’s not surprising (не удивительно = нет ничего удивительного /в том/) that a person is put on trial (что человека привлекают к суду; trial – испытание, проба; судебный процесс, суд) when he or she is accused of breaking the law (если он или она обвиняется в нарушении закона). However, if the person is found innocent (однако, если человек /этот/ будет признан невиновным; to find – находить; убеждаться, приходить к заключению, признавать), the accuser is immediately put to death (/то/ обвинитель немедленно подвергается казни), and the accused person is generously compensated (а обвиненный /им/ человек получает щедрое вознаграждение; to compensate – возмещать /убытки/; компенсировать; расплачиваться, вознаграждать /за нелегкий труд, лишения и т. п./) out of the accuser’s goods and land (/взыскиваемое/ с движимого и недвижимого имущества: «вещей и земли/землевладений» обвинителя; goods – вещи, имущество) for the hardship they have suffered (за испытанные им тяготы/лишения; hard – жесткий, твердый; трудный; тяжелый, тягостный /о времени/; they часто употребляется вместо he когда речь идет о человеке вообще, независимо от пола; to suffer – страдать; испытывать, претерпевать). The Emperor also gives the innocent person some public mark of favour (кроме того, император жалует невиновного каким-нибудь публичным знаком /своего/ благоволения; to give – дать, передать; /по/дарить; даровать, жаловать) and declares his innocence throughout the city (и объявляет о его невиновности всему городу; throughout – через, по всей площади, длине /чего-либо/).

There are some very peculiar laws and customs in this Empire. It’s not surprising that a person is put on trial when he or she is accused of breaking the law. However, if the person is found innocent, the accuser is immediately put to death, and the accused person is generously compensated out of the accuser’s goods and land for the hardship they have suffered. The Emperor also gives the innocent person some public mark of favour and declares his innocence throughout the city.

There are some very peculiar laws and customs in this Empire. It’s not surprising that a person is put on trial when he or she is accused of breaking the law. However, if the person is found innocent, the accuser is immediately put to death, and the accused person is generously compensated out of the accuser’s goods and land for the hardship they have suffered. The Emperor also gives the innocent person some public mark of favour and declares his innocence throughout the city.

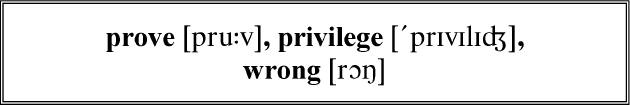

The people of Lilliput believe (лилипуты считают) that good government is based on reward and punishment (что хорошее государственное управление основывается на поощрении и наказании; government – руководство, /у/правление; правительство; государство). Anyone who can prove (всякий, кто сможет доказать) that he has kept the laws of the country for six years (что он соблюдал законы страны в течение шести лет) can claim certain privileges (может = имеет право претендовать на определенные/известные привилегии; to claim – требовать; предъявлять требования; заявлять о своих правах на что-либо) and a sum of money from a special fund (и денежную сумму из особого фонда). They thought it was wrong (они = лилипуты сочли неправильным/несправедливым) that our laws were enforced by punishment only (/то/, что у нас соблюдение законов обеспечивается только наказанием = страхом наказания; to enforce – принуждать, вынуждать /к чему-либо/; обязывать; обеспечивать соблюдение, исполнение; force – сила; насилие, принуждение), without any mention of reward (а о награде нигде и речи не ведется: «без всякого упоминания о награде/поощрении»).

The people of Lilliput believe that good government is based on reward and punishment. Anyone who can prove that he has kept the laws of the country for six years can claim certain privileges and a sum of money from a special fund. They thought it was wrong that our laws were enforced by punishment only, without any mention of reward.

The people of Lilliput believe that good government is based on reward and punishment. Anyone who can prove that he has kept the laws of the country for six years can claim certain privileges and a sum of money from a special fund. They thought it was wrong that our laws were enforced by punishment only, without any mention of reward.

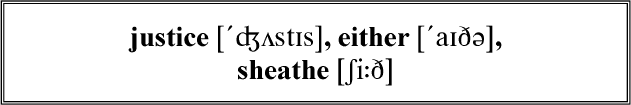

Their symbol of justice shows six eyes (их символ справедливости имеет: «показывает/являет» шесть глаз = символом справедливости/правосудия у них является фигура с шестью глазами), two in front, two behind (двумя спереди, двумя сзади) and one on either side (и по одному с боков: «с каждой стороны»; either – любой, каждый /из двух/; тот и другой; оба) to signify caution and attention (что означает осмотрительность и внимание). A bag of gold and a sheathed sword show (мешок золота и меч в ножнах /у нее в руках/ показывают; to sheathe – вкладывать в ножны) that they favour reward higher than punishment (что поощрение она ставит выше, чем наказание; to favour – благоволить; покровительствовать).

Their symbol of justice shows six eyes, two in front, two behind and one on either side to signify caution and attention. A bag of gold and a sheathed sword show that they favour reward higher than punishment.

Their symbol of justice shows six eyes, two in front, two behind and one on either side to signify caution and attention. A bag of gold and a sheathed sword show that they favour reward higher than punishment.

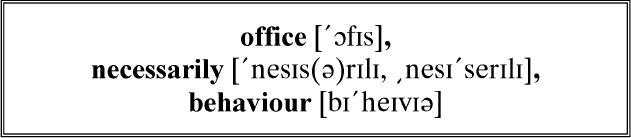

In choosing people for employment (при выборе кандидатов на /любую/ должность; employment – служба; занятие; работа; to employ – применять, использовать; предоставлять работу; нанимать), they care more about morals than ability (больше заботятся о нравственных качествах, чем об /умственных/ дарованиях; ability – способность; талант, дарование). They believe that the work of government is not a mystery (они = лилипуты полагают, что работа по управлению /общественными делами/ не является тайной) which can only be understood by a few exceptionally clever people (которая может быть постигнута только исключительно/необычайно умными людьми; exception – исключение; отклонение от нормы). They consider truth and justice to be virtues (они полагают, что честность и справедливость суть добродетели; truth – правда; истина; правдивость) everybody has (которые есть у каждого = доступные всем), and the practice of them (и /что/ упражнение в них; practice – практика; осуществление на практике; тренировка, упражнение), aided by experience and good intentions (вместе с опытностью и добрыми намерениями: «которому помогает опыт = при содействии опыта и…»; to aid – помогать, оказывать помощь, поддержку), would be enough to make any man fit for public office (достаточны для того, чтобы сделать любого человека пригодным для общественной должности). They do not believe that good behaviour necessarily comes with a great mind (они не думают, что благонравие является непременным спутником большого ума: «непременно сопровождает большой ум»; behaviour – образ действий, поступки; поведение; to behave – вести себя, поступать).

In choosing people for employment, they care more about morals than ability. They believe that the work of government is not a mystery which can only be understood by a few exceptionally clever people. They consider truth and justice to be virtues everybody has, and the practice of them, aided by experience and good intentions, would be enough to make any man fit for public office. They do not believe that good behaviour necessarily comes with a great mind.

In choosing people for employment, they care more about morals than ability. They believe that the work of government is not a mystery which can only be understood by a few exceptionally clever people. They consider truth and justice to be virtues everybody has, and the practice of them, aided by experience and good intentions, would be enough to make any man fit for public office. They do not believe that good behaviour necessarily comes with a great mind.

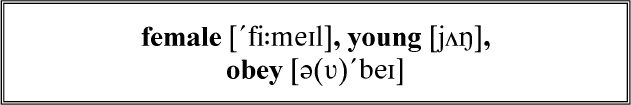

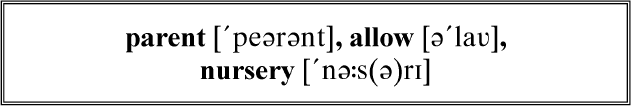

Their ideas about the duties of parents and children are very different from ours (их представления об обязанностях родителей и детей очень отличаются: «отличны» от наших). The Lilliputians believe that male and female come together (лилипуты считают, что мужчина и женщина сходятся) to continue the species like other animals (для продолжения рода, как /и/ остальные животные), and that their care for their young (и что их забота о детях; young – молодежь; детеныши, потомство) is simply a matter of obeying the laws of nature (проистекает единственно из естественной склонности: «есть просто/только вопрос следования законам природы»; to obey – подчиняться, слушаться). They therefore believe that a child is under no obligation to its parents (вследствие этого они считают, что ребенок не имеет никаких обязательств к своим родителям) for bringing him or her into the world (за то, что /они/ произвели его или ее на свет).

Their ideas about the duties of parents and children are very different from ours. The Lilliputians believe that male and female come together to continue the species like other animals, and that their care for their young is simply a matter of obeying the laws of nature. They therefore believe that a child is under no obligation to its parents for bringing him or her into the world.

Their ideas about the duties of parents and children are very different from ours. The Lilliputians believe that male and female come together to continue the species like other animals, and that their care for their young is simply a matter of obeying the laws of nature. They therefore believe that a child is under no obligation to its parents for bringing him or her into the world.

They believe that parents are the last people who should be allowed to educate their children (что воспитание детей менее всего может быть доверено их родителям: «что родители – самые неподходящие люди /из тех/, кому может быть позволено воспитывать…»; last – последний; самый неподходящий, нежелательный). They therefore have public nurseries in every town (поэтому в каждом городе существуют: «они имеют» общественные воспитательные заведения; nursery – детские ясли; детский сад; детское образовательное учреждение) where all parents, except farm workers, must send their infants of both sexes (куда все родители, кроме крестьян, должны отдавать: «отправлять» своих детей обоего пола; farm – ферма, крестьянское хозяйство; infant – младенец, маленький ребенок) when they are twenty months old (когда они достигают двадцатимесячного возраста).

They believe that parents are the last people who should be allowed to educate their children. They therefore have public nurseries in every town where all parents, except farm workers, must send their infants of both sexes when they are twenty months old.

They believe that parents are the last people who should be allowed to educate their children. They therefore have public nurseries in every town where all parents, except farm workers, must send their infants of both sexes when they are twenty months old.

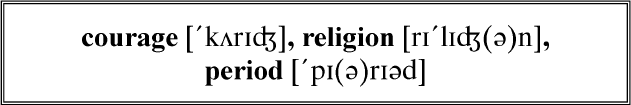

The nurseries for boys of noble birth have learned professors and teachers (воспитательные заведения для мальчиков благородного происхождения имеют опытных: «ученых/знающих» профессоров и учителей; birth – рождение; происхождение; professor – профессор; преподаватель высокого ранга; инструктор, руководитель, наставник). The children’s clothes and food are simple (одежда и пища детей просты = отличаются простотой), and they learn the importance of honour (и они постигают важность чести), justice (справедливости), courage (смелости), mercy (милосердия), religion and love of their country (религии и любви к своей стране/родине). They are kept busy at all times (они постоянно заняты делом; to keep busy – занимать работой), apart from short periods for eating and sleeping (не считая коротких/непродолжительных промежутков времени /отпущенных/ на еду и сон) and two hours of physical exercise (и двух часов физических упражнений).

The nurseries for boys of noble birth have learned professors and teachers. The children’s clothes and food are simple, and they learn the importance of honour, justice, courage, mercy, religion and love of their country. They are kept busy at all times, apart from short periods for eating and sleeping and two hours of physical exercise.

The nurseries for boys of noble birth have learned professors and teachers. The children’s clothes and food are simple, and they learn the importance of honour, justice, courage, mercy, religion and love of their country. They are kept busy at all times, apart from short periods for eating and sleeping and two hours of physical exercise.

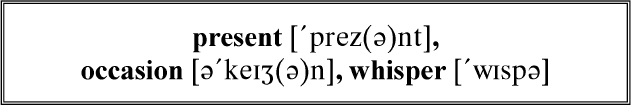

The children always go about together in groups (дети всегда ходят группами; about – кругом; повсюду), and always with a professor or teacher (и всегда вместе с наставником или учителем). Their parents are only allowed to see them twice a year (родителям разрешается увидеться с ними только два раза в год), for less than an hour (менее = не более часа), and they are allowed to kiss their child on meeting and parting (им позволяется поцеловать ребенка при встрече и расставании/прощанье). A teacher is always present on these occasions (в таких случаях = во время свиданий всегда присутствует учитель/воспитатель) and will not allow them to whisper (и /он/ не позволит им шептаться), use any words of affection (употреблять ласковые слова; affection – любовь, чувство близости, привязанность) or bring any presents of toys or sweets (или = и приносить в подарок игрушки или сласти/лакомства: «подарки в виде…»).

The children always go about together in groups, and always with a professor or teacher. Their parents are only allowed to see them twice a year, for less than an hour, and they are allowed to kiss their child on meeting and parting. A teacher is always present on these occasions and will not allow them to whisper, use any words of affection or bring any presents of toys or sweets.

The children always go about together in groups, and always with a professor or teacher. Their parents are only allowed to see them twice a year, for less than an hour, and they are allowed to kiss their child on meeting and parting. A teacher is always present on these occasions and will not allow them to whisper, use any words of affection or bring any presents of toys or sweets.

If the family fails to pay for the education and care of their child (если семья не пожелает заплатить за обучение и содержание своего ребенка; to fail to do smth. – не исполнить, не сделать какое-либо действие /из-за нежелания, неспособности, невозможности/; care – забота, попечение), the money will be taken by the Emperor’s officials (деньги будут взысканы /с них/ императорскими чиновниками).

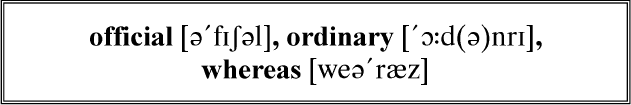

The nurseries for children of ordinary people are managed in a similar manner (воспитательные заведения для детей обычных людей устраиваются подобным /же/ образом; to manage – вести, организовывать /что-либо/; руководить, управлять), except that the children are apprenticed at the age of seven (за исключением того, что /тут/ дети в возрасте семи лет отдаются в учение ремеслу), whereas children of high rank continue their education until the age of fifteen (тогда как дети /людей/ высокого положения продолжают /общее/ образование до пятнадцати лет).

If the family fails to pay for the education and care of their child, the money will be taken by the Emperor’s officials.

If the family fails to pay for the education and care of their child, the money will be taken by the Emperor’s officials.

The nurseries for children of ordinary people are managed in a similar manner, except that the children are apprenticed at the age of seven, whereas children of high rank continue their education until the age of fifteen.

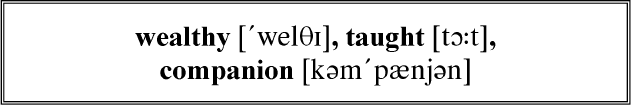

In the female nurseries (в женских воспитательных заведениях), the young girls from wealthy families are educated like the boys (девочки из состоятельных семей воспитываются /так же/, как и мальчики; wealth – богатство, состояние), except that their physical exercise is not so hard (за исключением того, что физические упражнения /для девочек/ более легкие: «не так трудны»). They learn some rules for domestic life (они обучаются правилам /ведения/ домашнего хозяйства), and they are taught that a wife should always be a reasonable and agreeable companion (и их учат /тому/, что жена всегда должна быть разумной и милой подругой /мужа/; to teach), since she cannot always be young (так как ее молодость не вечна: «она не может быть всегда молодой»). When the girls are twelve years old (когда девочкам/девушкам исполняется двенадцать лет), which is the age at which they may marry (то есть наступает пора замужества: «что является возрастом, в котором они могут выходить замуж»), they are taken home (их забирают домой).

In the female nurseries, the young girls from wealthy families are educated like the boys, except that their physical exercise is not so hard. They learn some rules for domestic life, and they are taught that a wife should always be a reasonable and agreeable companion, since she cannot always be young. When the girls are twelve years old, which is the age at which they may marry, they are taken home.

In the female nurseries, the young girls from wealthy families are educated like the boys, except that their physical exercise is not so hard. They learn some rules for domestic life, and they are taught that a wife should always be a reasonable and agreeable companion, since she cannot always be young. When the girls are twelve years old, which is the age at which they may marry, they are taken home.

The girls from ordinary families are taught all kinds of work (девочки из обычных семей обучаются всякого рода работам) suited to their sex and status (подобающим их полу и общественному положению; to suit – подходить, удовлетворять требованиям; годиться). The children who become apprentices do so at the age of seven (дети, которым предстоит заниматься ремеслами, в возрасте семи лет становятся подмастерьями: «дети, которые становятся ученицами/подмастерьями, делают так = это в возрасте…»). The rest are kept at school until they are eleven (остальные остаются в школе до одиннадцати лет).

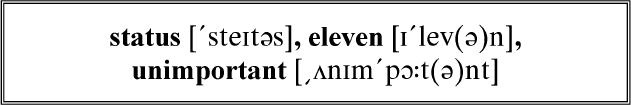

The poorest workers keep their children at home (самые бедные рабочие и крестьяне держат своих детей дома). Since their work is only to cultivate the earth (так как их работа – всего лишь обрабатывать землю), education is unimportant (/то их/ образование не имеет значения: «неважно/несущественно»). There are hospitals for the old and sick (для стариков и больных существуют больницы/богадельни), and begging is unknown in this Empire (и прошение милостыни есть /явление/ неизвестное в этой империи).

The girls from ordinary families are taught all kinds of work suited to their sex and status. The children who become apprentices do so at the age of seven. The rest are kept at school until they are eleven.

The girls from ordinary families are taught all kinds of work suited to their sex and status. The children who become apprentices do so at the age of seven. The rest are kept at school until they are eleven.

The poorest workers keep their children at home. Since their work is only to cultivate the earth, education is unimportant. There are hospitals for the old and sick, and begging is unknown in this Empire.

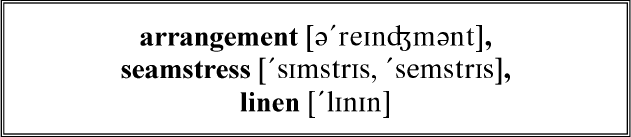

It may amuse the curious reader to know a little (любознательному читателю возможно будет забавно/интересно узнать немного/кое-что; may – может /для выражения разрешения, допускаемой возможности, предположения/; to amuse – развлекать; позабавить, развеселить) about my household arrangements (о моей повседневной жизни: «домашнем/бытовом укладе»; to arrange – приводить в порядок; расставлять; устраивать, организовывать; arrangement – приведение в порядок; установившийся порядок, устройство) during my nine months and thirteen days in this country (во время девяти месяцев и тринадцати дней /проведенных мною/ в этой стране). I had a table and chair made for me out of the largest trees in the royal park (у меня были стол и стул, сделанные из самых больших деревьев королевского парка). Two hundred seamstresses were employed to make me shirts (двести швей были призваны/наняты для того, чтобы изготовить мне рубахи; seam – шов; to seam – соединять швом, сшивать), sheets and table linen (простыни и столовое белье; linen – полотно; холст; белье), all of the strongest kind they could get (все – из самого прочного рода/сорта /полотна/, какое /только/ они могли достать; to get – получить; приобрести; добыть).

It may amuse the curious reader to know a little about my household arrangements during my nine months and thirteen days in this country. I had a table and chair made for me out of the largest trees in the royal park. Two hundred seamstresses were employed to make me shirts, sheets and table linen, all of the strongest kind they could get.

It may amuse the curious reader to know a little about my household arrangements during my nine months and thirteen days in this country. I had a table and chair made for me out of the largest trees in the royal park. Two hundred seamstresses were employed to make me shirts, sheets and table linen, all of the strongest kind they could get.

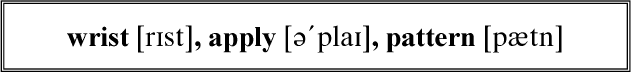

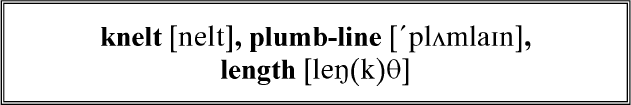

I lay on the ground to be measured (я лег на землю, чтобы меня измерили). One person stood at my neck (одна /швея/ стала у моей шеи), and another at my knees (другая у коленей), each holding a strong thread (каждая держа /в руках/ крепкую нить). A third person measured the thread with a ruler one inch long (третья измерила длину нити линейкой в один дюйм). Then they measured my right thumb (затем они смерили мой большой палец), for they calculated (поскольку они рассчитали = пользовались вычислением) that twice around the thumb is once around the wrist (что окружность запястья вдвое больше окружности большого пальца: «дважды вокруг большого пальца есть /то же, что/ один раз вокруг запястья»), the same applying to the neck and waist (то же = такое же соотношение применимо к шее и талии; to apply – применять /к чему-либо/; употреблять /для чего-либо/; касаться, относиться; применяться; распространяться /на кого-либо, что-либо/). And with the help of my old shirt (и при помощи моей старой рубахи), which they used as a pattern (которую они использовали в качестве образца), they fitted me exactly (они сшили мне все как раз по размеру; to fit – быть впору, в самый раз; подгонять, пригонять, прилаживать; exactly – в точности; точно; как раз).

I lay on the ground to be measured. One person stood at my neck, and another at my knees, each holding a strong thread. A third person measured the thread with a ruler one inch long. Then they measured my right thumb, for they calculated that twice around the thumb is once around the wrist, the same applying to the neck and waist. And with the help of my old shirt, which they used as a pattern, they fitted me exactly.

I lay on the ground to be measured. One person stood at my neck, and another at my knees, each holding a strong thread. A third person measured the thread with a ruler one inch long. Then they measured my right thumb, for they calculated that twice around the thumb is once around the wrist, the same applying to the neck and waist. And with the help of my old shirt, which they used as a pattern, they fitted me exactly.

Three hundred tailors were employed to make my clothes (триста портных были призваны для того, чтобы сшить мне одежду/костюм). They had another way of measuring (у них был другой способ измерения). I knelt down (я стал на колени; to kneel) and they put a ladder up against my neck (и они приставили к моей шее лестницу). One of them climbed the ladder (один из них взобрался по лестнице) and let a plumb-line fall from my collar to the floor (и опустил отвес от воротника до полу; line – веревка, шнур; to fall – падать; to let fall – опускать, спускать), which was the length of my coat (что /и/ составило длину моего кафтана).

Three hundred tailors were employed to make my clothes. They had another way of measuring. I knelt down and they put a ladder up against my neck. One of them climbed the ladder and let a plumb-line fall from my collar to the floor, which was the length of my coat.

Three hundred tailors were employed to make my clothes. They had another way of measuring. I knelt down and they put a ladder up against my neck. One of them climbed the ladder and let a plumb-line fall from my collar to the floor, which was the length of my coat.

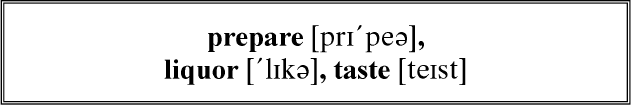

I had three hundred cooks to prepare my food (у меня было = мне выделили триста поваров, чтобы готовить = они готовили мою = мне пищу). They lived with their families in huts built around my house (они жили с семьями в домиках/бараках, построенных вокруг моего дома; hut – лачуга, хибара, хижина; барак). At meal times I took twenty waiters in my hand (во время приема пищи я брал в руку двадцать лакеев; to wait – ждать; прислуживать, обслуживать /за столом/; waiter – слуга, прислуживающий за столом; официант) and placed them on the table (и ставил их /себе/ на стол). A hundred more waited below on the ground (еще сотня /слуг/ прислуживали внизу на полу) with dishes of meat and barrels of wine (поднося блюда с едой/кушаньями и бочки с вином). The waiters above pulled up the food (лакеи /стоявшие/ наверху = на столе поднимали: «втаскивали» пищу наверх), as we would pull up a bucket from a well (как мы поднимаем ведро из колодца). A dish of their meat was a good mouthful (одного их блюда как раз хватало, чтобы наполнить рот; mouthful – количество еды, помещающееся в рот; кусок; глоток) and so was a barrel of their liquor (то же касается и бочки с вином; liquor – /спиртной/ напиток). Their mutton is not as good as ours (их баранина не так хороша, как наша = уступает нашей), but their beef is excellent (но /зато/ говядина превосходна). I usually ate a goose or turkey in one mouthful (гуся или индейку я съедал = проглатывал обыкновенно в один прием) and, I must confess, they tasted far better than ours (и я должен признать, они = эти птицы гораздо вкуснее наших; to taste – пробовать /на вкус/; иметь какой-либо вкус /о еде/; to taste good – быть вкусным; better – лучше /срав. степень от good/).

I had three hundred cooks to prepare my food. They lived with their families in huts built around my house. At meal times I took twenty waiters in my hand and placed them on the table. A hundred more waited below on the ground with dishes of meat and barrels of wine. The waiters above pulled up the food, as we would pull up a bucket from a well. A dish of their meat was a good mouthful and so was a barrel of their liquor. Their mutton is not as good as ours, but their beef is excellent. I usually ate a goose or turkey in one mouthful and, I must confess, they tasted far better than ours.

I had three hundred cooks to prepare my food. They lived with their families in huts built around my house. At meal times I took twenty waiters in my hand and placed them on the table. A hundred more waited below on the ground with dishes of meat and barrels of wine. The waiters above pulled up the food, as we would pull up a bucket from a well. A dish of their meat was a good mouthful and so was a barrel of their liquor. Their mutton is not as good as ours, but their beef is excellent. I usually ate a goose or turkey in one mouthful and, I must confess, they tasted far better than ours.

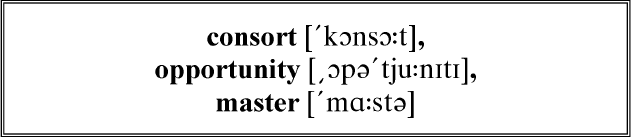

One day His Imperial Majesty requested (однажды его императорское величество изъявил желание) that he and his Consort might have the pleasure of dining with me (чтобы он и его супруга могли иметь удовольствие отобедать со мною; to request – просить, обращаться с просьбой, вежливым требованием). I placed them on state chairs upon my table (я поместил их на столе в парадных креслах) with their guards around them (с их = личной охраной вокруг них). Flimnap, the Lord High Treasurer, was there too (Флимнап, лорд верховный казначей, тоже присутствовал). I noticed that he often looked at me in an unpleasant way (я заметил, что он часто с недоброжелательством: «в неприятной/недружественной манере» посматривал на меня). I have reason to believe (у меня есть основания думать) that this visit from his Majesty gave Flimnap an opportunity (что это посещение его величества дало повод Флимнапу; opportunity – удобный случай, благоприятная возможность; шанс) of saying bad things about me to his master (выставить меня в дурном свете перед своим господином: «наговорить обо мне плохого своему…»).

One day His Imperial Majesty requested that he and his Consort might have the pleasure of dining with me. I placed them on state chairs upon my table with their guards around them. Flimnap, the Lord High Treasurer, was there too. I noticed that he often looked at me in an unpleasant way. I have reason to believe that this visit from his Majesty gave Flimnap an opportunity of saying bad things about me to his master.

One day His Imperial Majesty requested that he and his Consort might have the pleasure of dining with me. I placed them on state chairs upon my table with their guards around them. Flimnap, the Lord High Treasurer, was there too. I noticed that he often looked at me in an unpleasant way. I have reason to believe that this visit from his Majesty gave Flimnap an opportunity of saying bad things about me to his master.

Flimnap had always been my secret enemy (всегда был тайным моим врагом). He told the Emperor that his Treasury was poor (он сказал императору, что казна находится в плохом состоянии: «бедна») and that I had cost them over a million and a half sprugs (и что я стоил им = мое содержание обошлось им более чем в полтора миллиона спругов) – their greatest gold coin (их самая крупная золотая монета). He advised the Emperor (он советовал императору) to get rid of me as soon as possible (избавиться от меня как можно скорее).

Flimnap had always been my secret enemy. He told the Emperor that his Treasury was poor and that I had cost them over a million and a half sprugs (their greatest gold coin). He advised the Emperor to get rid of me as soon as possible.

Flimnap had always been my secret enemy. He told the Emperor that his Treasury was poor and that I had cost them over a million and a half sprugs (their greatest gold coin). He advised the Emperor to get rid of me as soon as possible.

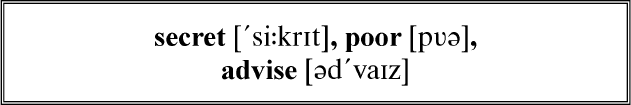

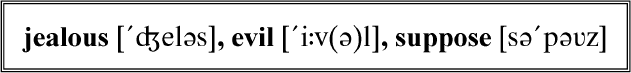

I am here obliged (на мне лежит обязанность: «тут я обязан») to save the reputation of an excellent lady (защитить честь одной достойной дамы; to save – спасать; охранять, защищать; excellent – превосходный; обладающий положительными качествами). Flimnap, the Treasurer, was jealous (был ревнив). He had heard some evil gossip (он услышал = до него дошли злые сплетни; gossip – болтовня; сплетня; слухи) about his wife being extremely fond of me (будто его жена невероятно в меня влюблена; about – вокруг, кругом; около; о, насчет, на тему; extremely – чрезвычайно, крайне, в высшей степени; fond – испытывающий нежные чувства; любящий), and that she was supposed to have once come privately to my home (и полагают, что однажды она тайно приезжала ко мне; to suppose – полагать, думать; предполагать). This, I declare to be untrue (я заявляю, что это ложь: «ложно/неверно»; true – правдивый, достоверный, истинный). Her Grace treated me as a friend (ее милость относилась ко мне как к другу). She often came to my house (она часто подъезжала к моему дому), but always with three other people in her coach (но всегда с тремя другими людьми в карете), as did many other ladies of the Court (как поступали /и/ многие другие придворные дамы).

I am here obliged to save the reputation of an excellent lady. Flimnap, the Treasurer, was jealous. He had heard some evil gossip about his wife being extremely fond of me, and that she was supposed to have once come privately to my home. This, I declare to be untrue. Her Grace treated me as a friend. She often came to my house, but always with three other people in her coach, as did many other ladies of the Court.

I am here obliged to save the reputation of an excellent lady. Flimnap, the Treasurer, was jealous. He had heard some evil gossip about his wife being extremely fond of me, and that she was supposed to have once come privately to my home. This, I declare to be untrue. Her Grace treated me as a friend. She often came to my house, but always with three other people in her coach, as did many other ladies of the Court.

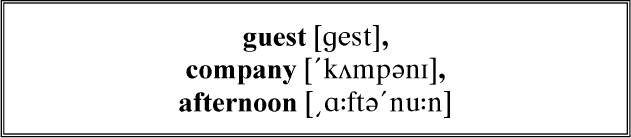

On these occasions, when a servant informed me I had guests (в подобных случаях, когда слуга докладывал мне о прибытии гостей: «сообщал, что у меня гости»), I went immediately to the door (я немедленно шел к двери). I have often had four coaches and horses on my table at the same time (часто на моем столе стояли: «у меня были» разом/одновременно четыре кареты с лошадьми), while I sat on my chair (в то время как я сидел на своем стуле/кресле) leaning my face towards the company (склонив лицо к гостям). I have passed many an agreeable afternoon in such company (я провел много приятных послеобеденных часов в таком обществе; noon – полдень; afternoon – время после полудня). This is only important because the reputation of a great lady is at stake (это важно = я счел нужным упомянуть об этом лишь потому, что под угрозой находится доброе имя высокопоставленной/знатной дамы; stake – ставка, заклад /в азартных играх/; to be at stake – быть поставленным на карту; находиться под угрозой) – to say nothing of my own reputation (не говоря уже о моем собственном).

On these occasions, when a servant informed me I had guests, I went immediately to the door. I have often had four coaches and horses on my table at the same time, while I sat on my chair leaning my face towards the company. I have passed many an agreeable afternoon in such company. This is only important because the reputation of a great lady is at stake – to say nothing of my own reputation.

On these occasions, when a servant informed me I had guests, I went immediately to the door. I have often had four coaches and horses on my table at the same time, while I sat on my chair leaning my face towards the company. I have passed many an agreeable afternoon in such company. This is only important because the reputation of a great lady is at stake – to say nothing of my own reputation.

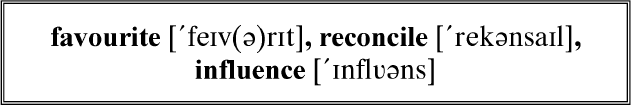

This scandal was the reason (эти наветы стали причиной /того/; scandal – скандал; постыдный факт; злословие, сплетни; клевета) that the Treasurer looked at his wife in such an unpleasant manner (что казначей так недружелюбно смотрел на свою жену), and looked at me even more unpleasantly (а на меня и подавно: «еще более нелюбезно/недружелюбно»). Although he was finally reconciled with her (хотя он в конце концов и примирился с женой), he still didn’t believe me (он все-таки мне не доверял). I also found that the Emperor (кроме того, я заметил, что император; to find – находить, обнаруживать; убеждаться, приходить к заключению), who was strongly influenced by his favourite Minister (который находился под сильным влиянием своего любимого министра; influence – влияние; to influence – оказывать влияние, влиять), was also losing interest in me (тоже стал относится ко мне более холодно: «стал терять ко мне интерес»).

This scandal was the reason that the Treasurer looked at his wife in such an unpleasant manner, and looked at me even more unpleasantly. Although he was finally reconciled with her, he still didn’t believe me. I also found that the Emperor, who was strongly influenced by his favourite Minister, was also losing interest in me.

This scandal was the reason that the Treasurer looked at his wife in such an unpleasant manner, and looked at me even more unpleasantly. Although he was finally reconciled with her, he still didn’t believe me. I also found that the Emperor, who was strongly influenced by his favourite Minister, was also losing interest in me.