Story of the Young Man in Holy Orders

(Повесть о молодом человеке духовного звания)

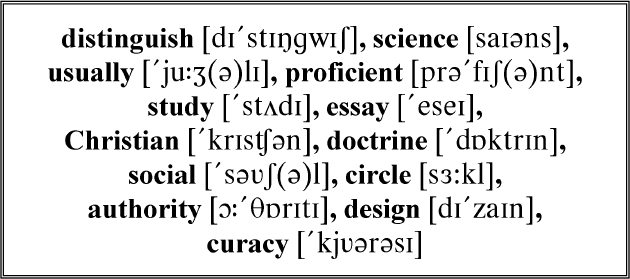

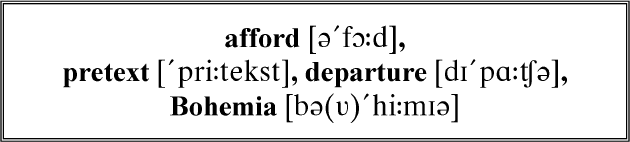

The Reverend Mr. Simon Rolles had distinguished himself in the Moral Sciences (преподобный мистер Саймон Роулз отличился на /поприще/ этики: «моральных наук»), and was more than usually proficient in the study of Divinity (и был более обычного искусен в изучении богословия). His essay “On the Christian Doctrine of the Social Obligations” obtained for him (его сочинение «О христианском учении об общественных обязанностях» получило для него = принесло ему), at the moment of its production (в момент его издания), a certain celebrity in the University of Oxford (некоторую известность в Оксфордском университете); and it was understood in clerical and learned circles (и было понято = считалось в церковных и ученых кругах) that young Mr. Rolles had in contemplation a considerable work (что у юного мистера Роулза был в обдумывании внушительный труд = что он обдумывал внушительный труд) – a folio, it was said (фолиант, как говорилось) – on the authority of the Fathers of the Church (об авторитете = авторитетности Отцов Церкви). These attainments, these ambitious designs, however (эти достижения, эти честолюбивые планы, однако), were far from helping him to any preferment (были далеки от того, чтобы помочь ему в продвижении по карьерной лестнице; to prefer – оказывать поддержку; способствовать; выдвигать, продвигать, повышать /в чине, звании/; предпочитать); and he was still in quest of his first curacy (и он все еще был в поисках своего первого церковного прихода) when a chance ramble in that part of London (когда случайная прогулка в той части Лондона), the peaceful and rich aspect of the garden (мирный и пышный вид сада), a desire for solitude and study (желание уединения и ученых занятий), and the cheapness of the lodging (и дешевизна жилья), led him to take up his abode with Mr. Raeburn (привели = побудили его снять жилище у мистера Рейберна), the nurseryman of Stockdove Lane (садовника на Стокдоув-лейн; nursery – питомник, рассадник; to nurse – выращивать, поливать /растение/).

The Reverend Mr. Simon Rolles had distinguished himself in the Moral Sciences, and was more than usually proficient in the study of Divinity. His essay “On the Christian Doctrine of the Social Obligations” obtained for him, at the moment of its production, a certain celebrity in the University of Oxford; and it was understood in clerical and learned circles that young Mr. Rolles had in contemplation a considerable work – a folio, it was said – on the authority of the Fathers of the Church. These attainments, these ambitious designs, however, were far from helping him to any preferment; and he was still in quest of his first curacy when a chance ramble in that part of London, the peaceful and rich aspect of the garden, a desire for solitude and study, and the cheapness of the lodging, led him to take up his abode with Mr. Raeburn, the nurseryman of Stockdove Lane.

The Reverend Mr. Simon Rolles had distinguished himself in the Moral Sciences, and was more than usually proficient in the study of Divinity. His essay “On the Christian Doctrine of the Social Obligations” obtained for him, at the moment of its production, a certain celebrity in the University of Oxford; and it was understood in clerical and learned circles that young Mr. Rolles had in contemplation a considerable work – a folio, it was said – on the authority of the Fathers of the Church. These attainments, these ambitious designs, however, were far from helping him to any preferment; and he was still in quest of his first curacy when a chance ramble in that part of London, the peaceful and rich aspect of the garden, a desire for solitude and study, and the cheapness of the lodging, led him to take up his abode with Mr. Raeburn, the nurseryman of Stockdove Lane.

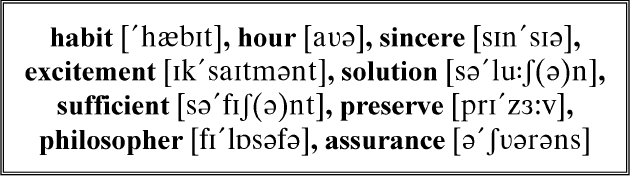

It was his habit (его привычкой было) every afternoon, after he had worked seven or eight hours on St. Ambrose or St. Chrysostom (каждый день, после того как он поработал семь-восемь часов над Св. Амвросием или Св. /Иоаннном/ Златоустом), to walk for a while in meditation among the roses (прогуливаться некоторое время в раздумьях среди роз). And this was usually one of the most productive moments of his day (и это было обычно одно из самых плодотворных мгновений его дня). But even a sincere appetite for thought (но даже искреннее стремление к размышлениям), and the excitement of grave problems awaiting solution (и возбуждение от серьезных проблем, ждущих разрешения), are not always sufficient to preserve the mind of the philosopher (не всегда достаточны, чтобы оградить ум философа) against the petty shocks and contacts of the world (от мелких столкновений и соприкосновений с миром). And when Mr. Rolles found General Vandeleur’s secretary (и когда мистер Роулз обнаружил секретаря генерала Венделера), ragged and bleeding (оборванного и кровоточащего), in the company of his landlord (в компании его хозяина); when he saw both change colour and seek to avoid his questions (когда он увидел, как оба /они/ меняются в лице и стараются уйти от его расспросов: «меняют цвет»); and, above all, when the former denied his own identity with the most unmoved assurance (и, важнее всего, когда первый /из них/ отрекся от собственной личности с непреклонной твердостью), he speedily forgot the Saints and Fathers in the vulgar interest of curiosity (он быстро позабыл Святых и Отцов /Церкви/ в низменном интересе любопытства = поддавшись низменному любопытству).

It was his habit every afternoon, after he had worked seven or eight hours on St. Ambrose or St. Chrysostom, to walk for a while in meditation among the roses. And this was usually one of the most productive moments of his day. But even a sincere appetite for thought, and the excitement of grave problems awaiting solution, are not always sufficient to preserve the mind of the philosopher against the petty shocks and contacts of the world. And when Mr. Rolles found General Vandeleur’s secretary, ragged and bleeding, in the company of his landlord; when he saw both change colour and seek to avoid his questions; and, above all, when the former denied his own identity with the most unmoved assurance, he speedily forgot the Saints and Fathers in the vulgar interest of curiosity.

It was his habit every afternoon, after he had worked seven or eight hours on St. Ambrose or St. Chrysostom, to walk for a while in meditation among the roses. And this was usually one of the most productive moments of his day. But even a sincere appetite for thought, and the excitement of grave problems awaiting solution, are not always sufficient to preserve the mind of the philosopher against the petty shocks and contacts of the world. And when Mr. Rolles found General Vandeleur’s secretary, ragged and bleeding, in the company of his landlord; when he saw both change colour and seek to avoid his questions; and, above all, when the former denied his own identity with the most unmoved assurance, he speedily forgot the Saints and Fathers in the vulgar interest of curiosity.

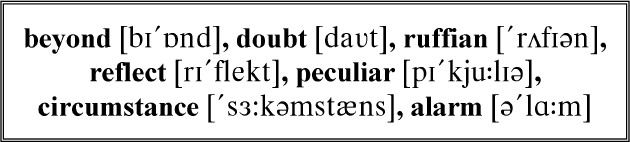

“I cannot be mistaken,” thought he (я не мог ошибиться, – думал он). “That is Mr. Hartley beyond a doubt (это мистер Хартли, вне всякого сомнения). How comes he in such a pickle (как он попал в такое жалкое положение; pickle – рассол; уксус для маринада; неприятное положение; плачевное состояние; сложная ситуация)? why does he deny his name (почему он отказывается от собственного имени: «отрицает…»)? and what can be his business with that black-looking ruffian, my landlord (и что у него за дела с этим свирепым разбойником – моим домовладельцем)?”

As he was thus reflecting (и пока он так размышлял), another peculiar circumstance attracted his attention (еще одно примечательное обстоятельство привлекло его внимание). The face of Mr. Raeburn appeared at a low window next the door (лицо мистера Рейберна появилось в низком окне рядом с дверью); and, as chance directed, his eyes met those of Mr. Rolles (и, как устроил случай= по случайности, его глаза встретились с глазами мистера Роулза). The nurseryman seemed disconcerted (садовник, казалось, был в замешательстве), and even alarmed (и даже встревожен); and immediately after the blind of the apartment was pulled sharply down (и сразу после /этого/ жалюзи в комнате было резко опущено).

“I cannot be mistaken,” thought he. “That is Mr. Hartley beyond a doubt. How comes he in such a pickle? why does he deny his name? and what can be his business with that black-looking ruffian, my landlord?”

“I cannot be mistaken,” thought he. “That is Mr. Hartley beyond a doubt. How comes he in such a pickle? why does he deny his name? and what can be his business with that black-looking ruffian, my landlord?”

As he was thus reflecting, another peculiar circumstance attracted his attention. The face of Mr. Raeburn appeared at a low window next the door; and, as chance directed, his eyes met those of Mr. Rolles. The nurseryman seemed disconcerted, and even alarmed; and immediately after the blind of the apartment was pulled sharply down.

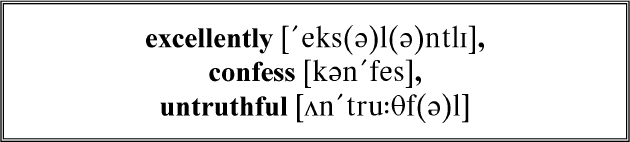

“This may all be very well,” reflected Mr. Rolles (это все может быть очень хорошо, – размышлял мистер Роулз); “it may be all excellently well (все может быть просто превосходно); but I confess freely that I do not think so (но, признаюсь откровенно, я так не думаю). Suspicious, underhand, untruthful, fearful of observation (подозрительные, неискренние, лживые, опасающиеся наблюдения = что их заметят) – I believe upon my soul,” he thought (я полагаю, клянусь моей душой, – думал он), “the pair are plotting some disgraceful action (эта парочка замышляет какой-то бесчестный поступок; plot – надел, делянка; кусок или участок земли /обычно занятый чем-либо или отведенный под какую-либо цель/; план, схема /этажа, здания и т. п./; карта /какой-либо местности, города и т. п./; интрига, заговор; козни).”

“This may all be very well,” reflected Mr. Rolles; “it may be all excellently well; but I confess freely that I do not think so. Suspicious, underhand, untruthful, fearful of observation – I believe upon my soul,” he thought, “the pair are plotting some disgraceful action.”

“This may all be very well,” reflected Mr. Rolles; “it may be all excellently well; but I confess freely that I do not think so. Suspicious, underhand, untruthful, fearful of observation – I believe upon my soul,” he thought, “the pair are plotting some disgraceful action.”

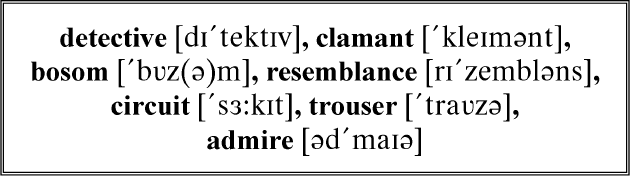

The detective that there is in all of us (сыщик, который есть во всех нас) awoke and became clamant in the bosom of Mr. Rolles (проснулся и стал настойчивым в груди мистера Роулза; to awake); and with a brisk, eager step (и бойким, нетерпеливым шагом), that bore no resemblance to his usual gait (который не нес = не имел сходства с его обычной походкой; to bear – нести), he proceeded to make the circuit of the garden (он принялся обходить сад по кругу). When he came to the scene of Harry’s escalade (когда он дошел до места эскалады = штурма /стены/ Гарри), his eye was at once arrested by a broken rosebush (его глаз был немедленно остановлен = его взгляд остановился на сломанном розовом кусте) and marks of trampling on the mould (и следах ног на взрыхленной земле). He looked up, and saw scratches on the brick (он взглянул вверх и увидел царапины на кирпиче), and a rag of trouser floating from a broken bottle (и обрывок штанины, развевающийся на бутылочном осколке). This, then, was the mode of entrance (так вот каков был способ войти) chosen by Mr. Raeburn’s particular friend (выбранный хорошим приятелем мистера Рейберна; to choose – выбирать)! It was thus that General Vandeleur’s secretary came to admire a flower-garden (вот как секретарь генерала Венделера вошел, чтобы полюбоваться на цветник)!

The detective that there is in all of us awoke and became clamant in the bosom of Mr. Rolles; and with a brisk, eager step, that bore no resemblance to his usual gait, he proceeded to make the circuit of the garden. When he came to the scene of Harry’s escalade, his eye was at once arrested by a broken rosebush and marks of trampling on the mould. He looked up, and saw scratches on the brick, and a rag of trouser floating from a broken bottle. This, then, was the mode of entrance chosen by Mr. Raeburn’s particular friend! It was thus that General Vandeleur’s secretary came to admire a flower-garden!

The detective that there is in all of us awoke and became clamant in the bosom of Mr. Rolles; and with a brisk, eager step, that bore no resemblance to his usual gait, he proceeded to make the circuit of the garden. When he came to the scene of Harry’s escalade, his eye was at once arrested by a broken rosebush and marks of trampling on the mould. He looked up, and saw scratches on the brick, and a rag of trouser floating from a broken bottle. This, then, was the mode of entrance chosen by Mr. Raeburn’s particular friend! It was thus that General Vandeleur’s secretary came to admire a flower-garden!

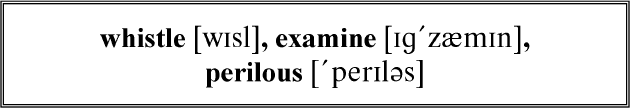

The young clergyman whistled softly to himself (молодой священник присвистнул тихо сам себе) as he stooped to examine the ground (когда он склонился, чтобы обследовать землю). He could make out where Harry had landed from his perilous leap (он смог разглядеть, куда приземлился Гарри из своего рискованного прыжка); he recognised the flat foot of Mr. Raeburn where it had sunk deeply in the soil (он узнал плоскую ступню мистера Рейберна, где она впечаталась глубоко в почву; to sink – погрузиться) as he pulled up the Secretary by the collar (когда он поднимал секретаря за ворот); nay, on a closer inspection, he seemed to distinguish the marks of groping fingers (более того, при ближайшем рассмотрении он, кажется, различил следы ищущих/ощупывающих пальцев), as though something had been spilt abroad (как будто что-то было рассыпано повсюду; to spill – просыпать, пролить) and eagerly collected (и поспешно собрано).

“Upon my word,” he thought, “the thing grows vastly interesting (честное слово, – подумал он, – это становится чрезвычайно интересным; vast – обширный).”

The young clergyman whistled softly to himself as he stooped to examine the ground. He could make out where Harry had landed from his perilous leap; he recognised the flat foot of Mr. Raeburn where it had sunk deeply in the soil as he pulled up the Secretary by the collar; nay, on a closer inspection, he seemed to distinguish the marks of groping fingers, as though something had been spilt abroad and eagerly collected.

The young clergyman whistled softly to himself as he stooped to examine the ground. He could make out where Harry had landed from his perilous leap; he recognised the flat foot of Mr. Raeburn where it had sunk deeply in the soil as he pulled up the Secretary by the collar; nay, on a closer inspection, he seemed to distinguish the marks of groping fingers, as though something had been spilt abroad and eagerly collected.

“Upon my word,” he thought, “the thing grows vastly interesting.”

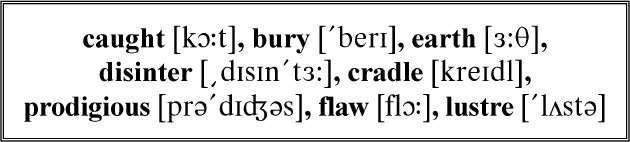

And just then he caught sight of something (и тогда он заметил что-то: «поймал вид чего-то») almost entirely buried in the earth (почти совершенно зарытое в землю = засыпанное землей). In an instant he had disinterred a dainty morocco case (в одно мгновение он откопал изящный сафьяновый футляр), ornamented and clasped in gilt (украшенный и застегнутый позолотой = с золоченым узором и застежкой). It had been trodden heavily underfoot (его сильно затоптали), and thus escaped the hurried search of Mr. Raeburn (и таким образом /он/ избежал внимания мистера Рейберна: «поспешного поиска»). Mr. Rolles opened the case (мистер Роулз открыл футляр), and drew a long breath of almost horrified astonishment (и задохнулся: «сделал долгий вдох» от изумления, близкого к ужасу; to horrify – ужасать; шокировать; to draw – тащить, волочить; тянуть; вбирать, вдыхать, втягивать); for there lay before him, in a cradle of green velvet (ибо перед ним лежал на подушке из зеленого бархата), a diamond of prodigious magnitude and of the finest water (алмаз огромного размера и чистейшей воды; prodigious – изумительный; непомерный, очень большой). It was of the bigness of a duck’s egg (он был величиной с утиное яйцо); beautifully shaped, and without a flaw (прекрасной формы и без единого изъяна); and as the sun shone upon it (и пока солнце светило на него = в солнечном свете), it gave forth a lustre like that of electricity (он испускал сияние вроде сияния электричества), and seemed to burn in his hand with a thousand internal fires (и, казалось, пылал в его руке тысячью внутренних огней).

And just then he caught sight of something almost entirely buried in the earth. In an instant he had disinterred a dainty morocco case, ornamented and clasped in gilt. It had been trodden heavily underfoot, and thus escaped the hurried search of Mr. Raeburn. Mr. Rolles opened the case, and drew a long breath of almost horrified astonishment; for there lay before him, in a cradle of green velvet, a diamond of prodigious magnitude and of the finest water. It was of the bigness of a duck’s egg; beautifully shaped, and without a flaw; and as the sun shone upon it, it gave forth a lustre like that of electricity, and seemed to burn in his hand with a thousand internal fires.

And just then he caught sight of something almost entirely buried in the earth. In an instant he had disinterred a dainty morocco case, ornamented and clasped in gilt. It had been trodden heavily underfoot, and thus escaped the hurried search of Mr. Raeburn. Mr. Rolles opened the case, and drew a long breath of almost horrified astonishment; for there lay before him, in a cradle of green velvet, a diamond of prodigious magnitude and of the finest water. It was of the bigness of a duck’s egg; beautifully shaped, and without a flaw; and as the sun shone upon it, it gave forth a lustre like that of electricity, and seemed to burn in his hand with a thousand internal fires.

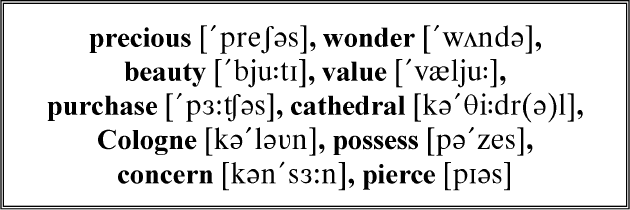

He knew little of precious stones (он знал мало о драгоценных камнях); but the Rajah’s Diamond was a wonder that explained itself (но Алмаз раджи был чудом, которое говорило за себя: «объясняло»); a village child, if he found it (деревенский ребенок, если бы он нашел его), would run screaming for the nearest cottage (побежал бы, кричащий= с криком, к ближайшему дому); and a savage would prostrate himself in adoration (и дикарь простерся бы /ниц/ в благоговении) before so imposing a fetish (пред столь внушительным фетишем). The beauty of the stone flattered the young clergyman’s eyes (красота камня ласкала взор молодого клирика: «глаза»); the thought of its incalculable value overpowered his intellect (мысль о его неисчислимой ценности одолела его разум). He knew that what he held in his hand (он знал, что то, что он держит в руке) was worth more than many years’ purchase of an archiepiscopal see (стóит больше, чем многолетний доход от престола архиепископа; worth – стóящий, достойный); that it would build cathedrals more stately than Ely or Cologne (что оно могло бы построить соборы более величественные, чем в Или или Кёльне); that he who possessed it was set free for ever from the primal curse (что тот, кто обладает им, освобожден навеки от первичного проклятия = от последствий первородного греха; to set free – отпустить на свободу), and might follow his own inclinations without concern or hurry (и может следовать собственным склонностям без беспокойства или спешки), without let or hindrance (без позволения или препятствия). And as he suddenly turned it (и когда он вдруг повернул его), the rays leaped forth again with renewed brilliancy (лучи засияли вновь с обновленной яркостью: «прыгнули вперед»; to leap – прыгать), and seemed to pierce his very heart (и, казалось, пронзили самое его сердце).

He knew little of precious stones; but the Rajah’s Diamond was a wonder that explained itself; a village child, if he found it, would run screaming for the nearest cottage; and a savage would prostrate himself in adoration before so imposing a fetish. The beauty of the stone flattered the young clergyman’s eyes; the thought of its incalculable value overpowered his intellect. He knew that what he held in his hand was worth more than many years’ purchase of an archiepiscopal see; that it would build cathedrals more stately than Ely or Cologne; that he who possessed it was set free for ever from the primal curse, and might follow his own inclinations without concern or hurry, without let or hindrance. And as he suddenly turned it, the rays leaped forth again with renewed brilliancy, and seemed to pierce his very heart.

He knew little of precious stones; but the Rajah’s Diamond was a wonder that explained itself; a village child, if he found it, would run screaming for the nearest cottage; and a savage would prostrate himself in adoration before so imposing a fetish. The beauty of the stone flattered the young clergyman’s eyes; the thought of its incalculable value overpowered his intellect. He knew that what he held in his hand was worth more than many years’ purchase of an archiepiscopal see; that it would build cathedrals more stately than Ely or Cologne; that he who possessed it was set free for ever from the primal curse, and might follow his own inclinations without concern or hurry, without let or hindrance. And as he suddenly turned it, the rays leaped forth again with renewed brilliancy, and seemed to pierce his very heart.

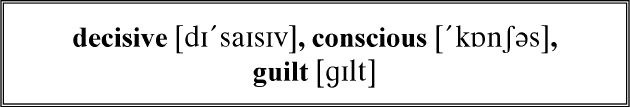

Decisive actions are often taken in a moment (решительные поступки часто совершаются в один момент) and without any conscious deliverance from the rational parts of man (и без какого-либо сознательного суждения рациональных частей /души/ человека; deliverance – высказанное мнение; to deliver – освобождать, избавлять; высказывать /что-либо/, высказываться; произносить, провозглашать). So it was now with Mr. Rolles (так было сейчас и с мистером Роулзом). He glanced hurriedly round (он огляделся поспешно по сторонам); beheld, like Mr. Raeburn before him, nothing but the sunlit flower-garden (не увидел, как и мистер Рейберн до него, ничего, кроме залитого солнцем цветника), the tall tree-tops, and the house with blinded windows (высоких верхушек деревьев и дома с зашторенными окнами); and in a trice he had shut the case (и в одно мгновение он захлопнул футляр; to shut – закрыть), thrust it into his pocket (сунул его в карман; to thrust – сунуть), and was hastening to his study with the speed of guilt (и поспешил в свой кабинет со скоростью вины = подгоняемый виной). The Reverend Simon Rolles had stolen the Rajah’s Diamond (преподобный Саймон Роулз украл Алмаз раджи; to steal – красть).

Decisive actions are often taken in a moment and without any conscious deliverance from the rational parts of man. So it was now with Mr. Rolles. He glanced hurriedly round; beheld, like Mr. Raeburn before him, nothing but the sunlit flower-garden, the tall tree-tops, and the house with blinded windows; and in a trice he had shut the case, thrust it into his pocket, and was hastening to his study with the speed of guilt. The Reverend Simon Rolles had stolen the Rajah’s Diamond.

Decisive actions are often taken in a moment and without any conscious deliverance from the rational parts of man. So it was now with Mr. Rolles. He glanced hurriedly round; beheld, like Mr. Raeburn before him, nothing but the sunlit flower-garden, the tall tree-tops, and the house with blinded windows; and in a trice he had shut the case, thrust it into his pocket, and was hastening to his study with the speed of guilt. The Reverend Simon Rolles had stolen the Rajah’s Diamond.

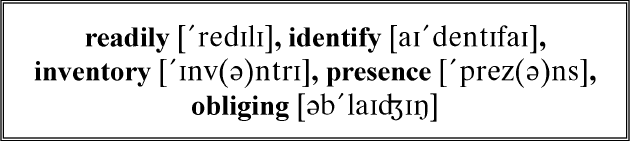

Early in the afternoon the police arrived with Harry Hartley (рано днем = вскоре после полудня пришли полицейские вместе с Гарри Хартли). The nurseryman, who was beside himself with terror (садовник, который был вне себя от ужаса), readily discovered his hoard (с готовностью раскрыл свой тайник); and the jewels were identified and inventoried in the presence of the Secretary (и драгоценности были опознаны и переписаны в присутствии секретаря). As for Mr. Rolles, he showed himself in a most obliging temper (что до мистера Роулза, он показал себя в самом услужливом нраве = был услужлив), communicated what he knew with freedom (сообщил то, что знал, с охотой), and professed regret that he could do no more (и выразил сожаление, что не может сделать больше) to help the officers in their duty (чтобы помочь полицейским в их деле).

“Still,” he added (все же, – добавил он), “I suppose your business is nearly at an end (я полагаю, ваше дело почти подошло к концу).”

Early in the afternoon the police arrived with Harry Hartley. The nurseryman, who was beside himself with terror, readily discovered his hoard; and the jewels were identified and inventoried in the presence of the Secretary. As for Mr. Rolles, he showed himself in a most obliging temper, communicated what he knew with freedom, and professed regret that he could do no more to help the officers in their duty.

Early in the afternoon the police arrived with Harry Hartley. The nurseryman, who was beside himself with terror, readily discovered his hoard; and the jewels were identified and inventoried in the presence of the Secretary. As for Mr. Rolles, he showed himself in a most obliging temper, communicated what he knew with freedom, and professed regret that he could do no more to help the officers in their duty.

“Still,” he added, “I suppose your business is nearly at an end.”

“By no means,” replied the man from Scotland Yard (никоим образом, – ответил человек из Скотленд-ярда); and he narrated the second robbery of which Harry had been the immediate victim (и он поведал /историю/ второго ограбления, немедленной жертвой которого пал Гарри), and gave the young clergyman a description of the more important jewels (и дал молодому клирику описание более важных драгоценностей) that were still not found (которые все еще не были найдены), dilating particularly on the Rajah’s Diamond (распространившись особенно = рассказав особенно подробно об Алмазе раджи).

“It must be worth a fortune,” observed Mr. Rolles (он должен стоить /целое/ состояние, – заметил мистер Роулз; worth – достойный, стóящий).

“Ten fortunes – twenty fortunes,” cried the officer (десять состояний – двадцать состояний, – воскликнул полицейский).

“By no means,” replied the man from Scotland Yard; and he narrated the second robbery of which Harry had been the immediate victim, and gave the young clergyman a description of the more important jewels that were still not found, dilating particularly on the Rajah’s Diamond.

“By no means,” replied the man from Scotland Yard; and he narrated the second robbery of which Harry had been the immediate victim, and gave the young clergyman a description of the more important jewels that were still not found, dilating particularly on the Rajah’s Diamond.

“It must be worth a fortune,” observed Mr. Rolles.

“Ten fortunes – twenty fortunes,” cried the officer.

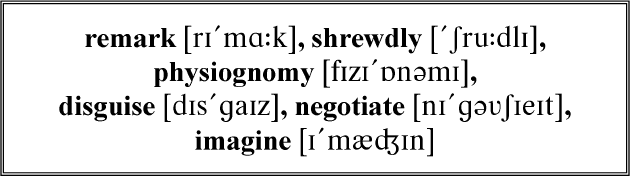

“The more it is worth,” remarked Simon shrewdly (чем больше он стóит, – заметил Саймон проницательно), “the more difficult it must be to sell (тем сложнее его, наверное, продать). Such a thing has a physiognomy not to be disguised (подобная вещь имеет наружность, которую не скрыть), and I should fancy a man might as easily negotiate St. Paul’s Cathedral (и я думаю, что человеку было бы так же просто = не труднее продать собор святого Павла).”

“Oh, truly!” said the officer (о, /это/ так! – сказал полицейский); “but if the thief be a man of any intelligence (но если вор окажется человеком хоть какого-либо рассудка), he will cut it into three or four (он распилит его на три или четыре /бриллианта/), and there will be still enough to make him rich (и все еще будет достаточно, чтобы сделать его богатым).”

“Thank you,” said the clergyman (спасибо, – сказал клирик). “You cannot imagine how much your conversation interests me (вы не можете себе представить, как сильно беседа с вами интересует меня).”

Whereupon the functionary admitted (тогда полицейский: «должностное лицо» признал) that they knew many strange things in his profession (что в его профессии знают обо многих странных вещах), and immediately after took his leave (и немедленно после /этого/ ушел: «взял свой уход»).

“The more it is worth,” remarked Simon shrewdly, “the more difficult it must be to sell. Such a thing has a physiognomy not to be disguised, and I should fancy a man might as easily negotiate St. Paul’s Cathedral.”

“The more it is worth,” remarked Simon shrewdly, “the more difficult it must be to sell. Such a thing has a physiognomy not to be disguised, and I should fancy a man might as easily negotiate St. Paul’s Cathedral.”

“Oh, truly!” said the officer; “but if the thief be a man of any intelligence, he will cut it into three or four, and there will be still enough to make him rich.”

“Thank you,” said the clergyman. “You cannot imagine how much your conversation interests me.”

Whereupon the functionary admitted that they knew many strange things in his profession, and immediately after took his leave.

Mr. Rolles regained his apartment (мистер Роулз вернулся в свою комнату). It seemed smaller and barer than usual (она казалась меньше и скуднее, чем обычно); the materials for his great work had never presented so little interest (материалы для его великого труда никогда /еще/ не представляли столь мало интереса); and he looked upon his library with the eye of scorn (и взглянул на свою библиотеку презрительным взглядом). He took down, volume by volume (он снял /с полки/, том за томом), several Fathers of the Church (несколько Отцов Церкви), and glanced them through (и просмотрел их); but they contained nothing to his purpose (но они не содержали ничего /подходящего/ для его цели).

Mr. Rolles regained his apartment. It seemed smaller and barer than usual; the materials for his great work had never presented so little interest; and he looked upon his library with the eye of scorn. He took down, volume by volume, several Fathers of the Church, and glanced them through; but they contained nothing to his purpose.

Mr. Rolles regained his apartment. It seemed smaller and barer than usual; the materials for his great work had never presented so little interest; and he looked upon his library with the eye of scorn. He took down, volume by volume, several Fathers of the Church, and glanced them through; but they contained nothing to his purpose.

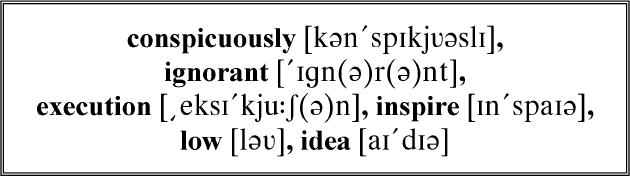

“These old gentlemen,” thought he (эти старые джентльмены, – подумал он), “are no doubt very valuable writers (несомненно, очень ценные авторы), but they seem to me conspicuously ignorant of life (но они кажутся мне заметно несведущими в жизни). Here am I, with learning enough to be a Bishop (вот я, с образованием, достаточным, чтобы быть епископом), and I positively do not know how to dispose of a stolen diamond (и я положительно не знаю, как сбыть краденый бриллиант). I glean a hint from a common policeman (я выудил совет у простого полисмена), and, with all my folios, I cannot so much as put it into execution (и, со всеми своими фолиантами, я даже не могу исполнить его: «не могу так много, как привести его в исполнение»). This inspires me with very low ideas of University training (это вселяет в меня весьма невысокое мнение об университетском образовании).”

“These old gentlemen,” thought he, “are no doubt very valuable writers, but they seem to me conspicuously ignorant of life. Here am I, with learning enough to be a Bishop, and I positively do not know how to dispose of a stolen diamond. I glean a hint from a common policeman, and, with all my folios, I cannot so much as put it into execution. This inspires me with very low ideas of University training.”

“These old gentlemen,” thought he, “are no doubt very valuable writers, but they seem to me conspicuously ignorant of life. Here am I, with learning enough to be a Bishop, and I positively do not know how to dispose of a stolen diamond. I glean a hint from a common policeman, and, with all my folios, I cannot so much as put it into execution. This inspires me with very low ideas of University training.”

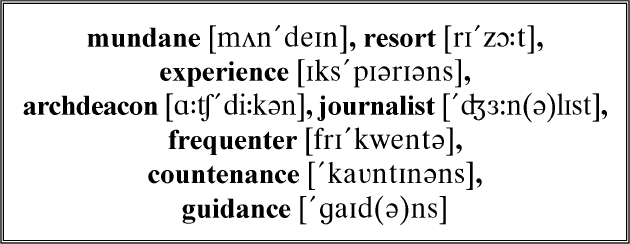

Herewith he kicked over his book-shelf (при этом он опрокинул пинком книжную полку) and, putting on his hat (и, надев шляпу), hastened from the house to the club of which he was a member (поспешил из дома в клуб, членом которого он состоял). In such a place of mundane resort (в таковом месте мирских сборищ) he hoped to find some man of good counsel (он надеялся найти какого-нибудь человека здравого рассудка) and a shrewd experience in life (и с практичным жизненным опытом). In the reading-room he saw many of the country clergy and an Archdeacon (в читальной комнате он увидел многих деревенских священников и одного архидьякона); there were three journalists and a writer upon the Higher Metaphysic (там были три журналиста и писатель /на темы/ высшей метафизики), playing pool (играющие на бильярде); and at dinner only the raff of ordinary club frequenters (а за обедом лишь сброд обычных посетителей клуба) showed their commonplace and obliterated countenances (показывали свои заурядные и ничего не выражающие лица). None of these, thought Mr. Rolles, would know more on dangerous topics than he knew himself (ни один из них, – подумал мистер Роулз, – не знает больше об опасных делах, чем он знал сам); none of them were fit (ни один из них не подходил; fit – подходящий) to give him guidance in his present strait (чтобы дать ему инструкцию в его теперешнем затруднительном положении).

Herewith he kicked over his book-shelf and, putting on his hat, hastened from the house to the club of which he was a member. In such a place of mundane resort he hoped to find some man of good counsel and a shrewd experience in life. In the reading-room he saw many of the country clergy and an Archdeacon; there were three journalists and a writer upon the Higher Metaphysic, playing pool; and at dinner only the raff of ordinary club frequenters showed their commonplace and obliterated countenances. None of these, thought Mr. Rolles, would know more on dangerous topics than he knew himself; none of them were fit to give him guidance in his present strait.

Herewith he kicked over his book-shelf and, putting on his hat, hastened from the house to the club of which he was a member. In such a place of mundane resort he hoped to find some man of good counsel and a shrewd experience in life. In the reading-room he saw many of the country clergy and an Archdeacon; there were three journalists and a writer upon the Higher Metaphysic, playing pool; and at dinner only the raff of ordinary club frequenters showed their commonplace and obliterated countenances. None of these, thought Mr. Rolles, would know more on dangerous topics than he knew himself; none of them were fit to give him guidance in his present strait.

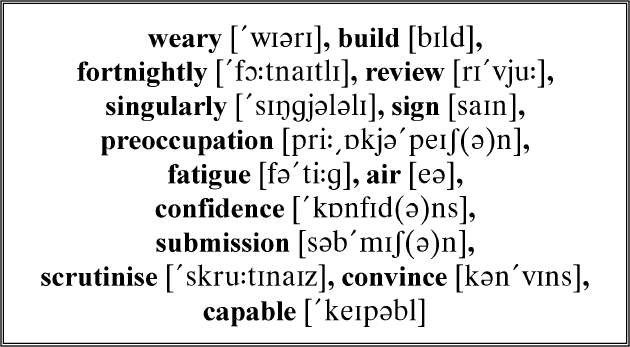

At length in the smoking-room (наконец в курительной комнате), up many weary stairs (вверх по многим ветхим ступеням = на следующем этаже), he hit upon a gentleman of somewhat portly build (он натолкнулся на джентльмена несколько полного сложения; to hit upon – натолкнуться; to hit – ударить) and dressed with conspicuous plainness (и одетого с бросающейся в глаза простотой). He was smoking a cigar and reading the Fortnightly Review (он курил сигару и читал «Двухнедельное обозрение»); his face was singularly free from all sign of preoccupation or fatigue (его лицо было необычайно свободно от знаков озабоченности или усталости); and there was something in his air (и было что-то в его облике) which seemed to invite confidence and to expect submission (что, казалось, вызывало доверие и ожидало = предполагало подчинение). The more the young clergyman scrutinised his features (чем больше молодой священник изучал его черты), the more he was convinced (тем больше он убеждался) that he had fallen on one capable of giving pertinent advice (что он напал на человека, способного дать дельный совет).

At length in the smoking-room, up many weary stairs, he hit upon a gentleman of somewhat portly build and dressed with conspicuous plainness. He was smoking a cigar and reading the Fortnightly Review; his face was singularly free from all sign of preoccupation or fatigue; and there was something in his air which seemed to invite confidence and to expect submission. The more the young clergyman scrutinised his features, the more he was convinced that he had fallen on one capable of giving pertinent advice.

At length in the smoking-room, up many weary stairs, he hit upon a gentleman of somewhat portly build and dressed with conspicuous plainness. He was smoking a cigar and reading the Fortnightly Review; his face was singularly free from all sign of preoccupation or fatigue; and there was something in his air which seemed to invite confidence and to expect submission. The more the young clergyman scrutinised his features, the more he was convinced that he had fallen on one capable of giving pertinent advice.

“Sir,” said he, “you will excuse my abruptness (сэр, – сказал он, – простите мою внезапность = неожиданные слова); but I judge you from your appearance to be (но по вашей наружности я полагаю, что вы: «я сужу вас по вашей наружности быть») pre-eminently a man of the world (совершенно человек мира = умудренный опытом).”

“I have indeed considerable claims to that distinction,” replied the stranger (у меня вправду есть серьезные претензии на эту почесть= я действительно могу претендовать на это звание, – ответил незнакомец), laying aside his magazine with a look of mingled amusement and surprise (откладывая в сторону свой журнал с видом смешанной забавы и удивления).

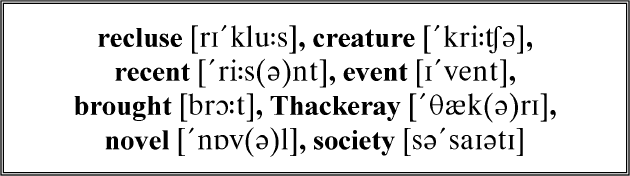

“I, sir,” continued the Curate, “am a recluse, a student (я, сэр, – продолжил священник, – затворник, ученый), a creature of ink-bottles and patristic folios (существо чернильниц и фолиантов Отцов Церкви). A recent event has brought my folly vividly before my eyes (недавнее происшествие поставило мою глупость живо перед моими глазами = раскрыло мне глаза на мою глупость), and I desire to instruct myself in life (и я желаю обучиться = больше узнать о жизни). By life,” he added, “I do not mean Thackeray’s novels (под жизнью, – добавил он, – я не подразумеваю романов Теккерея); but the crimes and secret possibilities of our society (но пороки и тайные возможности нашего общества), and the principles of wise conduct among exceptional events (и принципы разумного поведения при исключительных событиях). I am a patient reader (я терпеливый читатель); can the thing be learnt in books (может ли эта вещь быть выучена по книгам)?”

“Sir,” said he, “you will excuse my abruptness; but I judge you from your appearance to be pre-eminently a man of the world.”

“Sir,” said he, “you will excuse my abruptness; but I judge you from your appearance to be pre-eminently a man of the world.”

“I have indeed considerable claims to that distinction,” replied the stranger, laying aside his magazine with a look of mingled amusement and surprise.

“I, sir,” continued the Curate, “am a recluse, a student, a creature of ink-bottles and patristic folios. A recent event has brought my folly vividly before my eyes, and I desire to instruct myself in life. By life,” he added, “I do not mean Thackeray’s novels; but the crimes and secret possibilities of our society, and the principles of wise conduct among exceptional events. I am a patient reader; can the thing be learnt in books?”

“You put me in a difficulty,” said the stranger (вы ставите меня в затруднительное положение, – сказал незнакомец). “I confess I have no great notion of the use of books (признаюсь, что у меня невысокое мнение о пользе книг), except to amuse a railway journey (кроме того чтобы развлечь железнодорожную поездку = развлечься в…); although, I believe, there are some very exact treatises on astronomy (хотя, я полагаю, имеются некоторые весьма точные трактаты по астрономии), the use of the globes, agriculture, and the art of making paper flowers (использованию глобусов, сельскому хозяйству и искусству изготовления бумажных цветов). Upon the less apparent provinces of life (о менее заметных = о более тайных областях жизни) I fear you will find nothing truthful (боюсь, вы не найдете ничего достоверного). Yet stay,” he added, “have you read Gaboriau (хотя постойте, – добавил он, – вы читали Габорио)?”

Mr. Rolles admitted he had never even heard the name (мистер Роулз признался, что никогда даже не слышал этого имени).

“You put me in a difficulty,” said the stranger. “I confess I have no great notion of the use of books, except to amuse a railway journey; although, I believe, there are some very exact treatises on astronomy, the use of the globes, agriculture, and the art of making paper flowers. Upon the less apparent provinces of life I fear you will find nothing truthful. Yet stay,” he added, “have you read Gaboriau?”

“You put me in a difficulty,” said the stranger. “I confess I have no great notion of the use of books, except to amuse a railway journey; although, I believe, there are some very exact treatises on astronomy, the use of the globes, agriculture, and the art of making paper flowers. Upon the less apparent provinces of life I fear you will find nothing truthful. Yet stay,” he added, “have you read Gaboriau?”

Mr. Rolles admitted he had never even heard the name.

“You may gather some notions from Gaboriau,” resumed the stranger (вы можете получить некоторое представление /о жизни/ из Габорио, – продолжил незнакомец). “He is at least suggestive (он, по крайней мере, наводит на размышления); and as he is an author much studied by Prince Bismarck (а так как он писатель, прилежно читаемый князем Бисмарком), you will, at the worst, lose your time in good society (вы, в худшем случае, потеряете время в хорошей компании).”

“Sir,” said the Curate, “I am infinitely obliged by your politeness (сэр, – сказал священник, – я бесконечно обязан вашей любезности).”

“You have already more than repaid me,” returned the other (вы уже более чем отплатили мне, – ответил тот).

“How?” inquired Simon (как? – спросил Саймон).

“By the novelty of your request,” replied the gentleman (необычностью вашей просьбы, – ответил джентльмен); and with a polite gesture, as though to ask permission (и с вежливым жестом = учтиво поклонившись, словно чтобы испросить разрешения), he resumed the study of the Fortnightly Review (он возобновил изучение = чтение «Двухнедельного обозрения»).

“You may gather some notions from Gaboriau,” resumed the stranger. “He is at least suggestive; and as he is an author much studied by Prince Bismarck, you will, at the worst, lose your time in good society.”

“You may gather some notions from Gaboriau,” resumed the stranger. “He is at least suggestive; and as he is an author much studied by Prince Bismarck, you will, at the worst, lose your time in good society.”

“Sir,” said the Curate, “I am infinitely obliged by your politeness.”

“You have already more than repaid me,” returned the other.

“How?” inquired Simon.

“By the novelty of your request,” replied the gentleman; and with a polite gesture, as though to ask permission, he resumed the study of the Fortnightly Review.

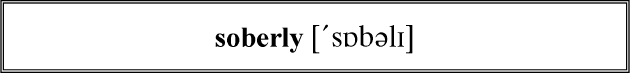

On his way home Mr. Rolles purchased a work on precious stones (по дороге домой мистер Роулз приобрел труд о драгоценных камнях) and several of Gaboriau’s novels (и несколько романов Габорио). These last he eagerly skimmed until an advanced hour in the morning (эти последние = романы он жадно листал до глубокой ночи: «до продвинутого часа утра»); but although they introduced him to many new ideas (но хотя они познакомили его со многими новыми мыслями), he could nowhere discover what to do with a stolen diamond (он не смог нигде найти, что делать с краденым алмазом). He was annoyed, moreover, to find the information scattered amongst romantic story-telling (он был раздосадован, к тому же, найдя эту информацию разбросанной /там и сям/ среди романтичного повествования), instead of soberly set forth after the manner of a manual (а не трезво изложенной по образцу учебника; to set forth – излагать); and he concluded that, even if the writer had thought much upon these subjects (и он заключил, что хотя автор и много думал об этих предметах), he was totally lacking in educational method (ему совершенно не хватало педагогического метода; to lack – не иметь, иметь недостаточно). For the character and attainments of Lecoq, however (перед личностью и достижениями Лекока, однако), he was unable to contain his admiration (он был неспособен сдержать восхищения).

On his way home Mr. Rolles purchased a work on precious stones and several of Gaboriau’s novels. These last he eagerly skimmed until an advanced hour in the morning; but although they introduced him to many new ideas, he could nowhere discover what to do with a stolen diamond. He was annoyed, moreover, to find the information scattered amongst romantic story-telling, instead of soberly set forth after the manner of a manual; and he concluded that, even if the writer had thought much upon these subjects, he was totally lacking in educational method. For the character and attainments of Lecoq, however, he was unable to contain his admiration.

On his way home Mr. Rolles purchased a work on precious stones and several of Gaboriau’s novels. These last he eagerly skimmed until an advanced hour in the morning; but although they introduced him to many new ideas, he could nowhere discover what to do with a stolen diamond. He was annoyed, moreover, to find the information scattered amongst romantic story-telling, instead of soberly set forth after the manner of a manual; and he concluded that, even if the writer had thought much upon these subjects, he was totally lacking in educational method. For the character and attainments of Lecoq, however, he was unable to contain his admiration.

“He was truly a great creature,” ruminated Mr. Rolles (он был поистине великим человеком, – размышлял мистер Роулз). “He knew the world as I know Paley’s Evidences (он знал свет, как я знаю «Свидетельства» Пейли). There was nothing that he could not carry to a termination with his own hand (не бывало ничего = не бывало дела, которого бы он не мог довести до конца своими собственными руками), and against the largest odds (и в самых безвыходных ситуациях: «вопреки наибольшему неравенству»). Heavens!” he broke out suddenly (Силы небесные! – воскликнул он внезапно; to break out – зд.: выпалить), “is not this the lesson (разве это не урок /мне/)? Must I not learn to cut diamonds for myself (не должен ли я выучиться резать алмазы сам)?”

“He was truly a great creature,” ruminated Mr. Rolles. “He knew the world as I know Paley’s Evidences. There was nothing that he could not carry to a termination with his own hand, and against the largest odds. Heavens!” he broke out suddenly, “is not this the lesson? Must I not learn to cut diamonds for myself?”

“He was truly a great creature,” ruminated Mr. Rolles. “He knew the world as I know Paley’s Evidences. There was nothing that he could not carry to a termination with his own hand, and against the largest odds. Heavens!” he broke out suddenly, “is not this the lesson? Must I not learn to cut diamonds for myself?”

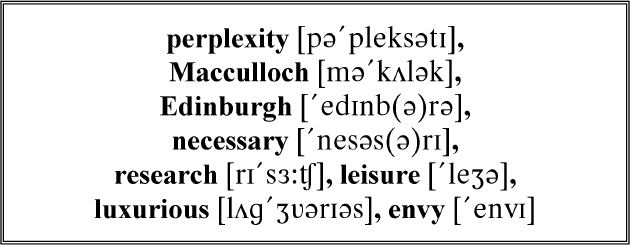

It seemed to him as if he had sailed at once out of his perplexities (ему показалось, будто он выплыл сразу из своих затруднений); he remembered that he knew a jeweller (он вспомнил, что знает одного ювелира), one B. Macculloch, in Edinburgh (некоего Б. Маккаллока из Эдинбурга), who would be glad to put him in the way of the necessary training (который был бы рад дать ему возможность необходимого обучения; to put in the way of smth. – дать возможность чего-либо); a few months, perhaps a few years, of sordid toil (несколько месяцев, возможно, несколько лет тяжелого труда), and he would be sufficiently expert to divide (и он будет достаточно сведущ, чтобы разделить) and sufficiently cunning to dispose with advantage of the Rajah’s Diamond (и достаточно хитер, чтобы избавиться с выгодой от Алмаза раджи). That done (это сделано = когда это будет сделано), he might return to pursue his researches at leisure (он может вернуться к своим исследованиям на досуге; to pursue – заниматься каким-либо делом; leisure – досуг, свободное время at leisure – на досуге; не спеша), a wealthy and luxurious student (богатым и живущим в роскоши ученым), envied and respected by all (которому все завидуют и которого все уважают; to envy – завидовать). Golden visions attended him through his slumber (золотые видения посещали его во время сна), and he awoke refreshed and light-hearted with the morning sun (и он проснулся освеженный и беззаботный с утренним солнцем = с восходом солнца).

It seemed to him as if he had sailed at once out of his perplexities; he remembered that he knew a jeweller, one B. Macculloch, in Edinburgh, who would be glad to put him in the way of the necessary training; a few months, perhaps a few years, of sordid toil, and he would be sufficiently expert to divide and sufficiently cunning to dispose with advantage of the Rajah’s Diamond. That done, he might return to pursue his researches at leisure, a wealthy and luxurious student, envied and respected by all. Golden visions attended him through his slumber, and he awoke refreshed and light-hearted with the morning sun.

It seemed to him as if he had sailed at once out of his perplexities; he remembered that he knew a jeweller, one B. Macculloch, in Edinburgh, who would be glad to put him in the way of the necessary training; a few months, perhaps a few years, of sordid toil, and he would be sufficiently expert to divide and sufficiently cunning to dispose with advantage of the Rajah’s Diamond. That done, he might return to pursue his researches at leisure, a wealthy and luxurious student, envied and respected by all. Golden visions attended him through his slumber, and he awoke refreshed and light-hearted with the morning sun.

Mr. Raeburn’s house was on that day to be closed by the police (дом мистера Рейберна должен был в тот день быть опечатан полицией), and this afforded a pretext for his departure (и это давало повод для его [священника] отъезда). He cheerfully prepared his baggage (он весело = в бодром настроении приготовил свой багаж), transported it to King’s Cross (отвез его на /вокзал/ Кингз-кросс: «крест короля»), where he left it in the cloak-room (где он оставил его в камере хранения; cloak – плащ; cloak-room – гардероб, раздевалка, вешалка; /ж.-д./ камера хранения), and returned to the club to while away the afternoon and dine (и вернулся в клуб, чтобы скоротать /там/ день и пообедать).

“If you dine here to-day, Rolles,” observed an acquaintance (если вы обедаете здесь сегодня, Роулз, – заметил один знакомый), “you may see two of the most remarkable men in England (вы можете увидеть двух из самых замечательных людей в Англии) – Prince Florizel of Bohemia, and old Jack Vandeleur (принца Флоризеля Богемского и старого Джека Венделера).”

Mr. Raeburn’s house was on that day to be closed by the police, and this afforded a pretext for his departure. He cheerfully prepared his baggage, transported it to King’s Cross, where he left it in the cloak-room, and returned to the club to while away the afternoon and dine.

Mr. Raeburn’s house was on that day to be closed by the police, and this afforded a pretext for his departure. He cheerfully prepared his baggage, transported it to King’s Cross, where he left it in the cloak-room, and returned to the club to while away the afternoon and dine.

“If you dine here to-day, Rolles,” observed an acquaintance, “you may see two of the most remarkable men in England – Prince Florizel of Bohemia, and old Jack Vandeleur.”

“I have heard of the Prince,” replied Mr. Rolles (я слыхал о принце, – ответил мистер Роулз); “and General Vandeleur I have even met in society (а генерала Венделера я даже встречал в обществе).”

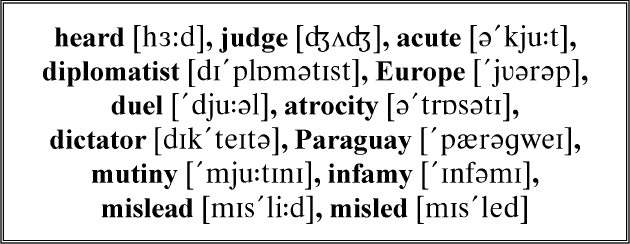

“General Vandeleur is an ass!” returned the other (генерал Венделер – осел! – возразил тот). “This is his brother John (это его брат Джон), the biggest adventurer, the best judge of precious stones (самый отъявленный искатель приключений, лучший знаток драгоценных камней), and one of the most acute diplomatists in Europe (и один из самых проницательных дипломатов в Европе). Have you never heard of his duel with the Duc de Val d’Orge (вы никогда не слышали о его дуэли с герцогом де Вальдорж)? of his exploits and atrocities when he was Dictator of Paraguay (о его подвигах и зверствах, когда он был диктатором Парагвая)? of his dexterity in recovering Sir Samuel Levi’s jewellery (о его ловкости при возвращении = разыскании драгоценностей сэра Сэмюэла Леви)? nor of his services in the Indian Mutiny (и о его услугах /правительству/ во время Индийского восстания) – services by which the Government profited (услугах, из которых правительство извлекло выгоду), but which the Government dared not recognise (но которые правительство не посмело признать /открыто/)? You make me wonder what we mean by fame (вы заставляете меня задаваться вопросом, что же мы подразумеваем под славой; to wonder – удивляться; задаваться вопросом), or even by infamy (или даже под дурной славой); for Jack Vandeleur has prodigious claims to both (ибо у Джека Венделера есть огромные притязания и на то, и на другое = по праву претендует). Run downstairs,” he continued (бегите вниз, – продолжил он), “take a table near them, and keep your ears open (займите столик рядом с ними и держите уши открытыми). You will hear some strange talk, or I am much misled (вы услышите какие-нибудь необычайные речи, или я сильно заблуждаюсь; to mislead – сбивать с пути, вести по неправильному пути; вводить в заблуждение).”

“I have heard of the Prince,” replied Mr. Rolles; “and General Vandeleur I have even met in society.”

“I have heard of the Prince,” replied Mr. Rolles; “and General Vandeleur I have even met in society.”

“General Vandeleur is an ass!” returned the other. “This is his brother John, the biggest adventurer, the best judge of precious stones, and one of the most acute diplomatists in Europe. Have you never heard of his duel with the Duc de Val d’Orge? of his exploits and atrocities when he was Dictator of Paraguay? of his dexterity in recovering Sir Samuel Levi’s jewellery? nor of his services in the Indian Mutiny – services by which the Government profited, but which the Government dared not recognise? You make me wonder what we mean by fame, or even by infamy; for Jack Vandeleur has prodigious claims to both. Run downstairs,” he continued, “take a table near them, and keep your ears open. You will hear some strange talk, or I am much misled.”

“But how shall I know them?” inquired the clergyman (но как я узнаю их? – спросил священник).

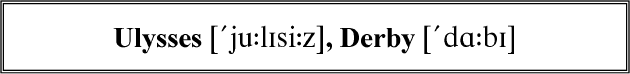

“Know them!” cried his friend (/как/ узнаете их! – воскликнул его приятель); “why, the Prince is the finest gentleman in Europe (ну как же, принц – самый блестящий джентльмен в Европе), the only living creature who looks like a king (единственное живое существо, которое выглядит, как король); and as for Jack Vandeleur (а что до Джека Венделера), if you can imagine Ulysses at seventy years of age (если вы можете представить себе Улисса в возрасте семидесяти лет), and with a sabre-cut across his face (с сабельным шрамом через /все/ лицо), you have the man before you (вот он: «вы имеете этого человека перед вами»)! Know them, indeed (/как/ узнать их, право слово)! Why, you could pick either of them out of a Derby day (вы могли бы найти любого из них /в толпе/ в день скачек: «из дня дерби»; either – один из двух; такой или другой; тот или другой; каждый, любой /из двух/, и тот и другой; Derby – скачки)!”

“But how shall I know them?” inquired the clergyman.

“But how shall I know them?” inquired the clergyman.

“Know them!” cried his friend; “why, the Prince is the finest gentleman in Europe, the only living creature who looks like a king; and as for Jack Vandeleur, if you can imagine Ulysses at seventy years of age, and with a sabre-cut across his face, you have the man before you! Know them, indeed! Why, you could pick either of them out of a Derby day!”

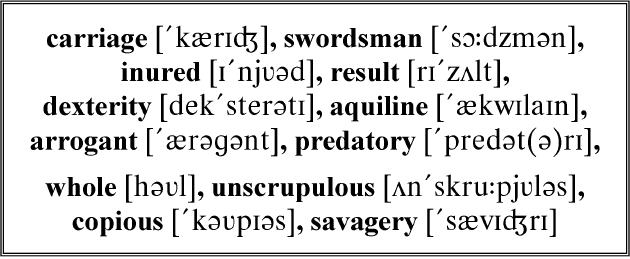

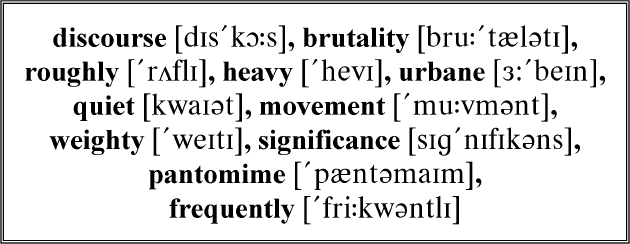

Rolles eagerly hurried to the dining-room (Роулз нетерпеливо поспешил в столовую). It was as his friend had asserted (получилось /именно/ так, как утверждал его приятель); it was impossible to mistake the pair in question (было невозможно ошибиться в этой паре; in question – обсуждаемый, данный, о котором идет речь: «в обсуждении»). Old John Vandeleur was of a remarkable force of body (старый Джон Венделер был /человек/ замечательной физической силы: «силы тела»), and obviously broken to the most difficult exercises (и явно приученный к самым тяжелым нагрузкам; broken to smth. – приученный к чему-либо; to break – ломать). He had neither the carriage of a swordsman, nor of a sailor (у него не было ни осанки фехтовальщика, ни /осанки/ моряка), nor yet of one much inured to the saddle (ни человека, основательно привыкшего к седлу = наездника); but something made up of all these (но /у него было/ что-то, составленное из всего этого), and the result and expression of many different habits and dexterities (и результат и выражение многих различных привычек и умений). His features were bold and aquiline (его черты были смелыми и орлиными = орлиный профиль); his expression arrogant and predatory (выражение его /лица/ – надменным и хищным); his whole appearance that of a swift, violent, unscrupulous man of action (вся его внешность – внешностью быстрого = горячего, отчаянного, неразборчивого в средствах человека действия); and his copious white hair and the deep sabre-cut that traversed his nose and temple (а его густые белые = седые волосы и глубокий сабельный шрам, который пересекал его нос и висок) added a note of savagery to a head already remarkable and menacing in itself (добавляли оттенок свирепости голове = лицу, уже самому по себе примечательному и грозному; to menace – грозить, угрожать).

Rolles eagerly hurried to the dining-room. It was as his friend had asserted; it was impossible to mistake the pair in question. Old John Vandeleur was of a remarkable force of body, and obviously broken to the most difficult exercises. He had neither the carriage of a swordsman, nor of a sailor, nor yet of one much inured to the saddle; but something made up of all these, and the result and expression of many different habits and dexterities. His features were bold and aquiline; his expression arrogant and predatory; his whole appearance that of a swift, violent, unscrupulous man of action; and his copious white hair and the deep sabre-cut that traversed his nose and temple added a note of savagery to a head already remarkable and menacing in itself.

Rolles eagerly hurried to the dining-room. It was as his friend had asserted; it was impossible to mistake the pair in question. Old John Vandeleur was of a remarkable force of body, and obviously broken to the most difficult exercises. He had neither the carriage of a swordsman, nor of a sailor, nor yet of one much inured to the saddle; but something made up of all these, and the result and expression of many different habits and dexterities. His features were bold and aquiline; his expression arrogant and predatory; his whole appearance that of a swift, violent, unscrupulous man of action; and his copious white hair and the deep sabre-cut that traversed his nose and temple added a note of savagery to a head already remarkable and menacing in itself.

In his companion, the Prince of Bohemia, Mr. Rolles was astonished to recognise the gentleman (в его спутнике, принце Богемии, мистер Роулз был поражен узнать джентльмена) who had recommended him the study of Gaboriau (который порекомендовал ему изучение Габорио). Doubtless Prince Florizel, who rarely visited the club (без сомнения, принц Флоризель, который редко посещал клуб), of which, as of most others, he was an honorary member (которого, как и большинства остальных, он был почетным членом), had been waiting for John Vandeleur when Simon accosted him on the previous evening (ожидал Джона Венделера, когда Саймон заговорил с ним прошлым вечером).

The other diners had modestly retired into the angles of the room (другие обедавшие скромно удалились = разошлись по углам комнаты), and left the distinguished pair in a certain isolation (и оставили эту выдающуюся пару = пару знаменитостей в некотором уединении), but the young clergyman was unrestrained by any sentiment of awe (но молодой священник не был сдерживаем каким-либо чувством благоговения), and, marching boldly up (и, смело подойдя /к ним/; to march up – подойти), took his place at the nearest table (занял место за ближайшим столиком).

In his companion, the Prince of Bohemia, Mr. Rolles was astonished to recognise the gentleman who had recommended him the study of Gaboriau. Doubtless Prince Florizel, who rarely visited the club, of which, as of most others, he was an honorary member, had been waiting for John Vandeleur when Simon accosted him on the previous evening.

In his companion, the Prince of Bohemia, Mr. Rolles was astonished to recognise the gentleman who had recommended him the study of Gaboriau. Doubtless Prince Florizel, who rarely visited the club, of which, as of most others, he was an honorary member, had been waiting for John Vandeleur when Simon accosted him on the previous evening.

The other diners had modestly retired into the angles of the room, and left the distinguished pair in a certain isolation, but the young clergyman was unrestrained by any sentiment of awe, and, marching boldly up, took his place at the nearest table.

The conversation was, indeed, new to the student’s ears (этот разговор был действительно нов для ушей ученого). The ex-Dictator of Paraguay stated many extraordinary experiences in different quarters of the world (бывший диктатор Парагвая поведал о многих необычайных приключениях в разных уголках света); and the Prince supplied a commentary (а принц вставлял замечания) which, to a man of thought, was even more interesting (которые для человека мысли = думающего были еще интереснее) than the events themselves (чем сами происшествия). Two forms of experience were thus brought together (две формы опыта были, таким образом, сведены вместе) and laid before the young clergyman (и выложены перед молодым священником; to lay – класть); and he did not know which to admire the most (и он не знал, кем восхищаться больше) – the desperate actor or the skilled expert in life (отчаянным деятелем или умудренным знатоком жизни); the man who spoke boldly of his own deeds and perils (человеком, который прямо говорил о своих собственных поступках и /пережитых/ опасностях; boldly – отважно, смело; дерзко), or the man who seemed, like a god, to know all things and to have suffered nothing (или человеком, который, казалось, подобно божеству, знал все вещи и не испытал ни одной; to suffer – страдать; испытывать, претерпевать).

The conversation was, indeed, new to the student’s ears. The ex-Dictator of Paraguay stated many extraordinary experiences in different quarters of the world; and the Prince supplied a commentary which, to a man of thought, was even more interesting than the events themselves. Two forms of experience were thus brought together and laid before the young clergyman; and he did not know which to admire the most – the desperate actor or the skilled expert in life; the man who spoke boldly of his own deeds and perils, or the man who seemed, like a god, to know all things and to have suffered nothing.

The conversation was, indeed, new to the student’s ears. The ex-Dictator of Paraguay stated many extraordinary experiences in different quarters of the world; and the Prince supplied a commentary which, to a man of thought, was even more interesting than the events themselves. Two forms of experience were thus brought together and laid before the young clergyman; and he did not know which to admire the most – the desperate actor or the skilled expert in life; the man who spoke boldly of his own deeds and perils, or the man who seemed, like a god, to know all things and to have suffered nothing.

The manner of each aptly fitted with his part in the discourse (манера каждого /из них/ точно подходила его роли в разговоре; aptly – впритирку, без зазора, впору). The Dictator indulged in brutalities alike of speech and gesture (диктатор позволял себе резкости как в речи, так и в жестах; brutality – грубость; жестокость); his hand opened and shut (его рука открывалась и закрывалась = кулак сжимался и разжимался) and fell roughly on the table (и опускался: «падал» грубо на стол); and his voice was loud and heavy (а его голос был громким и тяжелым = напористым). The Prince, on the other hand (принц, с другой стороны), seemed the very type of urbane docility and quiet (казался образцом учтивой деликатности и сдержанности; docility – послушание, повиновение, покорность; податливость: tact and docility – такт и уступчивость; quiet – тишина, безмолвие; покой, спокойствие); the least movement, the least inflection, had with him a weightier significance (мельчайшее движение, мельчайшая интонация имели у него более весомое значение) than all the shouts and pantomime of his companion (чем все крики и жесты его товарища); and if ever, as must frequently have been the case (и если когда-нибудь, как, должно быть, часто бывало), he described some experience personal to himself (он описывал собственные приключения: «приключение, личное для него»), it was so aptly dissimulated (оно бывало так умело замаскировано) as to pass unnoticed with the rest (чтобы пройти незамеченным между остальных; rest – остаток).

The manner of each aptly fitted with his part in the discourse. The Dictator indulged in brutalities alike of speech and gesture; his hand opened and shut and fell roughly on the table; and his voice was loud and heavy. The Prince, on the other hand, seemed the very type of urbane docility and quiet; the least movement, the least inflection, had with him a weightier significance than all the shouts and pantomime of his companion; and if ever, as must frequently have been the case, he described some experience personal to himself, it was so aptly dissimulated as to pass unnoticed with the rest.

The manner of each aptly fitted with his part in the discourse. The Dictator indulged in brutalities alike of speech and gesture; his hand opened and shut and fell roughly on the table; and his voice was loud and heavy. The Prince, on the other hand, seemed the very type of urbane docility and quiet; the least movement, the least inflection, had with him a weightier significance than all the shouts and pantomime of his companion; and if ever, as must frequently have been the case, he described some experience personal to himself, it was so aptly dissimulated as to pass unnoticed with the rest.

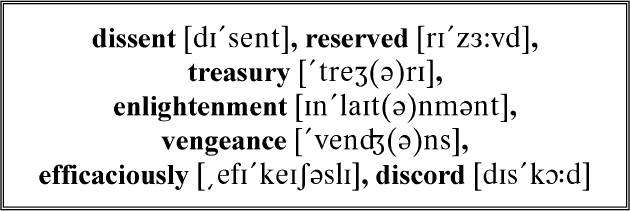

At length the talk wandered on to the late robberies and the Rajah’s Diamond (наконец разговор обратился к недавним ограблениям и к Алмазу раджи; to wander – бродить).

“That diamond would be better in the sea,” observed Prince Florizel (этому алмазу было бы лучше оказаться в море, – заметил принц Флоризель).

“As a Vandeleur,” replied the Dictator, “your Highness may imagine my dissent (как Венделер= так как я член семьи Венделер, – ответил диктатор, – ваше высочество может представить себе мое несогласие).”

“I speak on grounds of public policy,” pursued the Prince (я говорю из соображений общественных интересов, – продолжил принц). “Jewels so valuable should be reserved for the collection of a Prince (сокровища столь ценные должны оставаться для коллекции сюзерена; to reserve – сохранять, сберегать) or the treasury of a great nation (или для казны великой нации). To hand them about among the common sort of men (пустить их по рукам среди простых людей) is to set a price on Virtue’s head (это назначить цену за голову Добродетели = погубить ее, вынести ей приговор); and if the Rajah of Kashgar – a Prince, I understand, of great enlightenment (и если кашгарский раджа – властитель, как я понимаю, большой просвещенности) – desired vengeance upon the men of Europe (желал бы отмщения людям Европы), he could hardly have gone more efficaciously about his purpose (он вряд ли мог бы приступить более эффективно к этому делу; to go about – приступить к делу, заняться) than by sending us this apple of discord (чем послав нам это яблоко раздора).

At length the talk wandered on to the late robberies and the Rajah’s Diamond.

At length the talk wandered on to the late robberies and the Rajah’s Diamond.

“That diamond would be better in the sea,” observed Prince Florizel.

“As a Vandeleur,” replied the Dictator, “your Highness may imagine my dissent.”

“I speak on grounds of public policy,” pursued the Prince. “Jewels so valuable should be reserved for the collection of a Prince or the treasury of a great nation. To hand them about among the common sort of men is to set a price on Virtue’s head; and if the Rajah of Kashgar – a Prince, I understand, of great enlightenment – desired vengeance upon the men of Europe, he could hardly have gone more efficaciously about his purpose than by sending us this apple of discord.

“There is no honesty too robust for such a trial (нет честности слишком крепкой для такого испытания). I myself, who have many duties and many privileges of my own (я сам, у которого много обязанностей и много собственных привилегий) – I myself, Mr. Vandeleur, could scarce handle the intoxicating crystal and be safe (я сам, мистер Венделер, едва ли мог бы держать в руках этот опьяняющий кристалл и быть в безопасности = устоять). As for you, who are a diamond hunter by taste and profession (что касается вас, вы – охотник за алмазами по склонности и ремеслу), I do not believe there is a crime in the calendar (я не думаю, что есть такое преступление в списке = на свете) you would not perpetrate (/которого/ вы бы не совершили) – I do not believe you have a friend in the world whom you would not eagerly betray (я не думаю, что у вас есть на свете друг, которого вы бы не предали с готовностью) – I do not know if you have a family (не знаю, есть ли у вас семья), but if you have I declare you would sacrifice your children (но если есть, я заявляю, что вы бы пожертвовали своими детьми) – and all this for what (и все это для чего)? Not to be richer (не чтобы быть богаче), nor to have more comforts or more respect (не чтобы иметь больше удобства или больше уважения), but simply to call this diamond yours for a year or two until you die (но просто чтобы называть этот алмаз своим год или два, пока вы не умрете), and now and again to open a safe (и то и дело открывать сейф) and look at it as one looks at a picture (и смотреть на него, как смотрят на картину).”

“There is no honesty too robust for such a trial. I myself, who have many duties and many privileges of my own – I myself, Mr. Vandeleur, could scarce handle the intoxicating crystal and be safe. As for you, who are a diamond hunter by taste and profession, I do not believe there is a crime in the calendar you would not perpetrate – I do not believe you have a friend in the world whom you would not eagerly betray – I do not know if you have a family, but if you have I declare you would sacrifice your children – and all this for what? Not to be richer, nor to have more comforts or more respect, but simply to call this diamond yours for a year or two until you die, and now and again to open a safe and look at it as one looks at a picture.”

“There is no honesty too robust for such a trial. I myself, who have many duties and many privileges of my own – I myself, Mr. Vandeleur, could scarce handle the intoxicating crystal and be safe. As for you, who are a diamond hunter by taste and profession, I do not believe there is a crime in the calendar you would not perpetrate – I do not believe you have a friend in the world whom you would not eagerly betray – I do not know if you have a family, but if you have I declare you would sacrifice your children – and all this for what? Not to be richer, nor to have more comforts or more respect, but simply to call this diamond yours for a year or two until you die, and now and again to open a safe and look at it as one looks at a picture.”

“It is true,” replied Vandeleur (это правда, – ответил Венделер). “I have hunted most things, from men and women down to mosquitos (я охотился за многими вещами, от мужчин и женщин до москитов); I have dived for coral (я нырял за кораллами); I have followed both whales and tigers (я преследовал и китов, и тигров); and a diamond is the tallest quarry of the lot (и алмаз – высочайшая = лучшая дичь из всей партии/ассортимента). It has beauty and worth (у него есть красота и ценность); it alone can properly reward the ardours of the chase (он один может как следует вознаградить пылкость погони). At this moment, as your Highness may fancy (в настоящий момент, как ваше высочество может представить себе = догадаться), I am upon the trail (я /иду/ по следу); I have a sure knack, a wide experience (у меня определенная сноровка, обширный опыт; knack – умение, сноровка; /уст./ хитрость, трюк, уловка); I know every stone of price in my brother’s collection (я знаю каждый стóящий камень в коллекции моего брата) as a shepherd knows his sheep (как пастух знает своих овец); and I wish I may die (и я желаю, чтобы я мог умереть) if I do not recover them every one (если я их не верну все до единого: «каждый»; to recover – вновь обретать; возвращать, получать обратно)!”

“It is true,” replied Vandeleur. “I have hunted most things, from men and women down to mosquitos; I have dived for coral; I have followed both whales and tigers; and a diamond is the tallest quarry of the lot. It has beauty and worth; it alone can properly reward the ardours of the chase. At this moment, as your Highness may fancy, I am upon the trail; I have a sure knack, a wide experience; I know every stone of price in my brother’s collection as a shepherd knows his sheep; and I wish I may die if I do not recover them every one!”

“It is true,” replied Vandeleur. “I have hunted most things, from men and women down to mosquitos; I have dived for coral; I have followed both whales and tigers; and a diamond is the tallest quarry of the lot. It has beauty and worth; it alone can properly reward the ardours of the chase. At this moment, as your Highness may fancy, I am upon the trail; I have a sure knack, a wide experience; I know every stone of price in my brother’s collection as a shepherd knows his sheep; and I wish I may die if I do not recover them every one!”

“Sir Thomas Vandeleur will have great cause to thank you,” said the Prince (у сэра Томаса Венделера будет хорошая причина благодарить вас, – сказал принц).

“I am not so sure,” returned the Dictator, with a laugh (я не так уверен /в этом/, – ответил диктатор с усмешкой). “One of the Vandeleurs will (у одного из Венделеров будет /хорошая причина поблагодарить меня/). Thomas or John (у Фомы или у Иоанна) – Peter or Paul (у Петра или у Павла) – we are all apostles (все мы апостолы /одной веры/).”

“I did not catch your observation,” said the Prince with some disgust (я не понял ваших слов: «не поймал вашего замечания», – сказал принц с некоторым раздражением; disgust – отвращение; досада, раздражение).

And at the same moment the waiter informed Mr. Vandeleur (в тот же момент официант уведомил мистера Венделера) that his cab was at the door (что его кеб у двери).

Mr. Rolles glanced at the clock (мистер Роулз взглянул на часы), and saw that he also must be moving (и увидел, что он тоже должен уходить); and the coincidence struck him sharply and unpleasantly (и это совпадение произвело на него неприятное впечатление: «ударило его остро и неприятно»; to strike – ударить; произвести впечатление), for he desired to see no more of the diamond hunter (так как он желал больше не видеть этого охотника за алмазами).

“Sir Thomas Vandeleur will have great cause to thank you,” said the Prince.

“Sir Thomas Vandeleur will have great cause to thank you,” said the Prince.

“I am not so sure,” returned the Dictator, with a laugh. “One of the Vandeleurs will. Thomas or John – Peter or Paul – we are all apostles.”

“I did not catch your observation,” said the Prince with some disgust.

And at the same moment the waiter informed Mr. Vandeleur that his cab was at the door.

Mr. Rolles glanced at the clock, and saw that he also must be moving; and the coincidence struck him sharply and unpleasantly, for he desired to see no more of the diamond hunter.

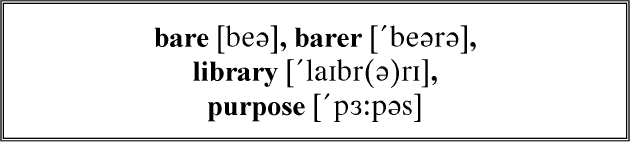

Much study having somewhat shaken the young man’s nerves (/так как/ усердные ученые занятия несколько расшатали нервы молодого человека), he was in the habit of travelling in the most luxurious manner (у него была привычка путешествовать самым роскошным = комфортабельным образом: «он был в привычке…»); and for the present journey he had taken a sofa in the sleeping carriage (и для настоящего путешествия он занял диван = место в спальном вагоне).

“You will be very comfortable,” said the guard (вам будет очень уютно, – сказал кондуктор); “there is no one in your compartment (в вашем купе никого нет /кроме вас/), and only one old gentleman in the other end (и только один пожилой джентльмен в другом конце /вагона/).”

Much study having somewhat shaken the young man’s nerves, he was in the habit of travelling in the most luxurious manner; and for the present journey he had taken a sofa in the sleeping carriage.

Much study having somewhat shaken the young man’s nerves, he was in the habit of travelling in the most luxurious manner; and for the present journey he had taken a sofa in the sleeping carriage.

“You will be very comfortable,” said the guard; “there is no one in your compartment, and only one old gentleman in the other end.”

It was close upon the hour (был уже почти час /отправления/; close – близко, close upon – почти), and the tickets were being examined (и /как раз/ проверяли билеты), when Mr. Rolles beheld this other fellow-passenger ushered by several porters into his place (когда мистер Роулз увидел /своего/ спутника, провожаемого несколькими носильщиками к своему месту); certainly, there was not another man in the world whom he would not have preferred (поистине, не было другого человека на свете, кого бы он не предпочел = он предпочел бы, чтобы это был кто угодно другой) – for it was old John Vandeleur, the ex-Dictator (ибо это был старый Джон Венделер, бывший диктатор).

It was close upon the hour, and the tickets were being examined, when Mr. Rolles beheld this other fellow-passenger ushered by several porters into his place; certainly, there was not another man in the world whom he would not have preferred – for it was old John Vandeleur, the ex-Dictator.

It was close upon the hour, and the tickets were being examined, when Mr. Rolles beheld this other fellow-passenger ushered by several porters into his place; certainly, there was not another man in the world whom he would not have preferred – for it was old John Vandeleur, the ex-Dictator.