Part Six

Bends

Bends are used to tie the ends of two—or occasionally three—ropes together. In accomplishing this, a bend is generally an easier, quicker, and less bulky solution than tying two loop knots through one another. Some bends work best with ropes of similar diameter, while others are optimized for ropes of different sizes, and some work well in flat materials such as leather straps or nylon webbing.

44.

Uses: load bearing; bending flat materials or rope

Pros: easy to tie; secure; straps remain flat

Cons: difficult to untie in rope

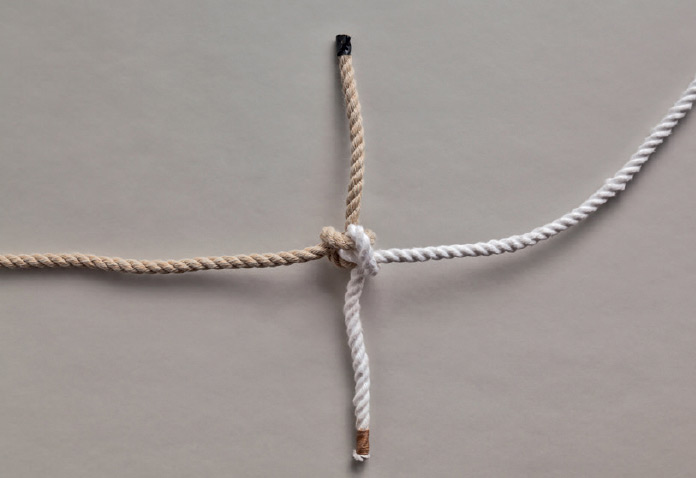

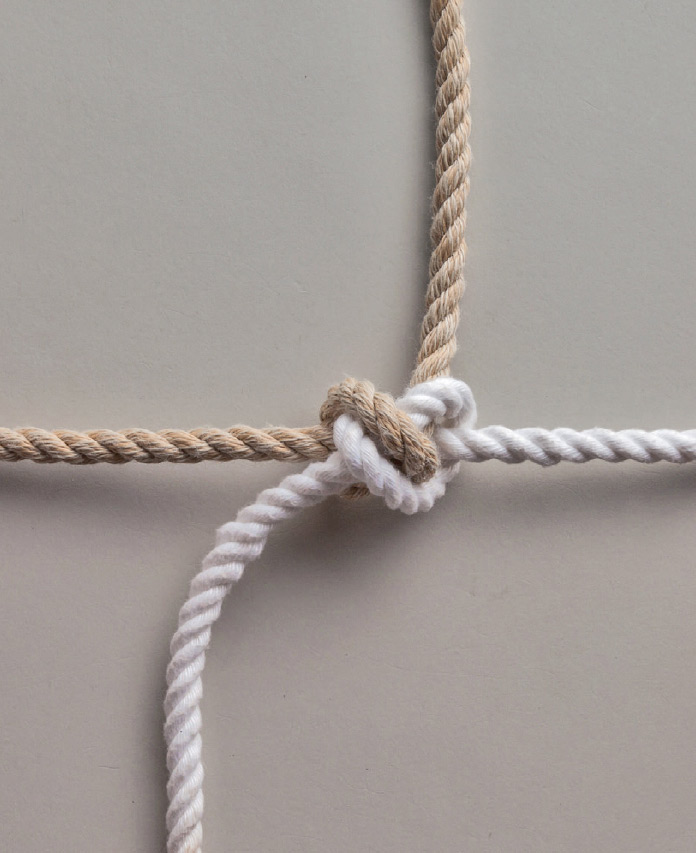

45.

Uses: temporary light-duty applications where constant load will be maintained

Pros: simple to tie and untie in ropes of equal or different diameter

Cons: insecure when unloaded

46.

Uses: joining lines of dissimilar diameters; connecting heaving and messenger lines

Pros: less prone to slippage than a Sheet Bend; easy to tie and untie

Cons: relatively insecure when unloaded; may catch on obstructions if it will be dragged

47.

Uses: joining two lines that will be dragged or towed; dinghy painters; towlines

Pros: reduced chance of catching on obstruction, less drag when towed in water

Cons: somewhat insecure if not kept under load

48.

Uses: two-to-one or one-to-two towing

Pros: an easy three-way bend; easy to untie; works with different size ropes

Cons: insecure

49.

Uses: standing rigging, static and dynamic loads

Pros: secure

Cons: difficult to untie in natural fiber rope; only for ropes of equal diameter

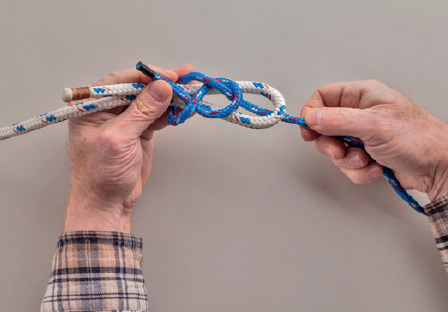

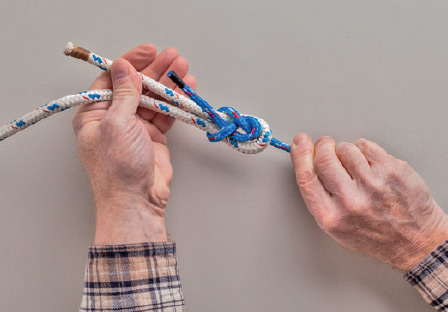

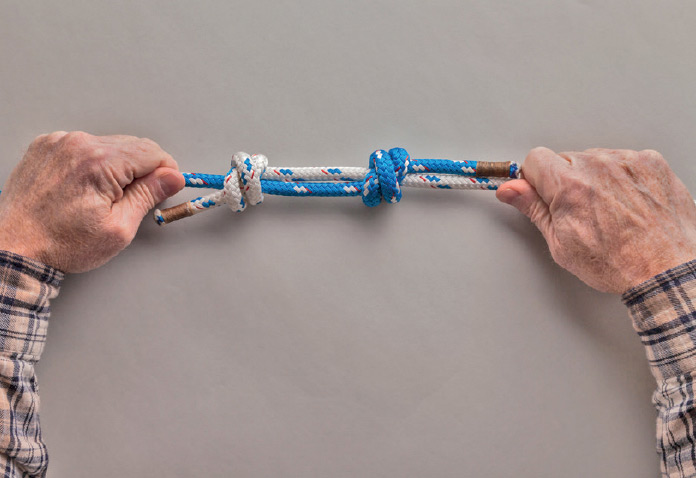

50.

Uses: joining ropes for climbing, mountaineering

Pros: very secure and strong, absorbs shock

Cons: none known

51.

Uses: joining heavy, stiff ropes

Pros: more secure than Sheet Bend or Reef Knot, easy to untie

Cons: reduces rope strength considerably

52.

Uses: load lifting, safety

Pros: strong; remains secure when unloaded; easily untied

Cons: tricky to tie; bulky; may catch when dragged

53.

Uses: load bearing

Pros: remains secure with or without load; holds slippery rope well

Cons: fussy to tie in hand; hard to untie

54.

Uses: load bearing in thin rope, bungee cord

Pros: very secure

Cons: fussy to tie in hand, difficult to check; hard to untie

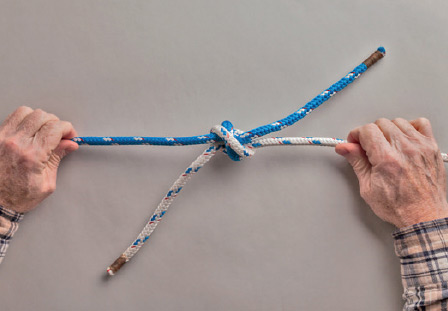

55.

Uses: joining small or medium cordage

Pros: easy and quick to tie

Cons: can capsize or slip under tension; difficult to untie

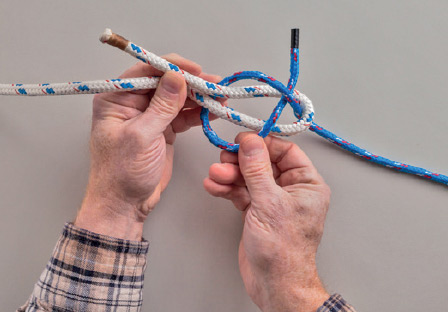

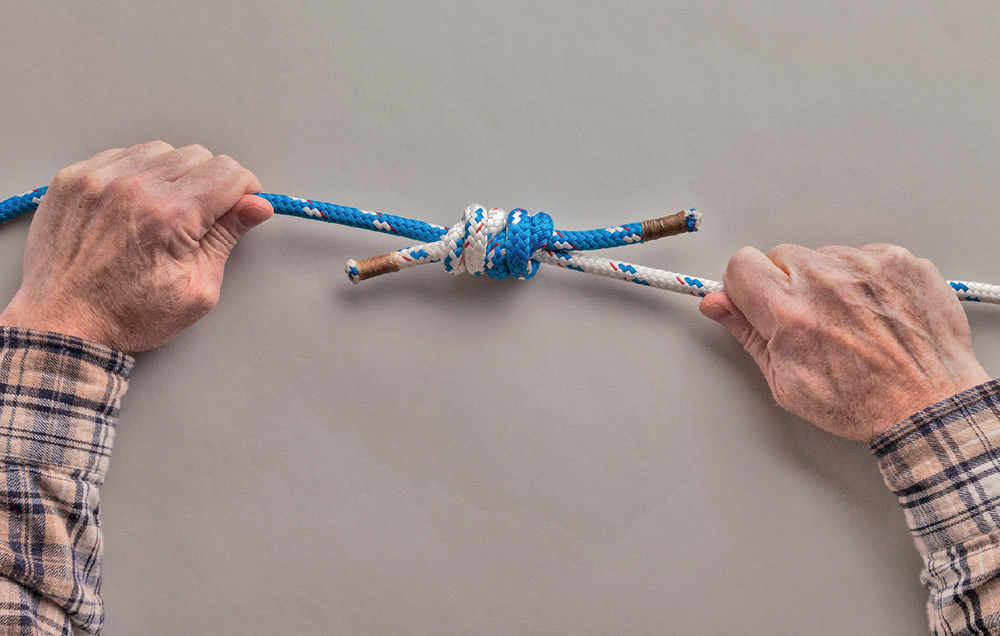

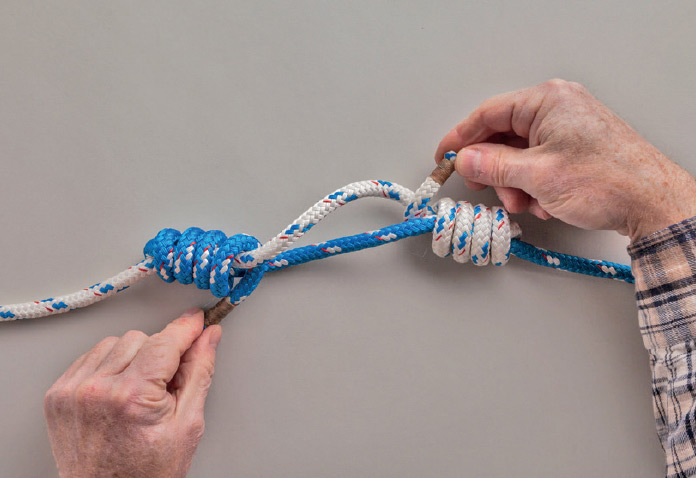

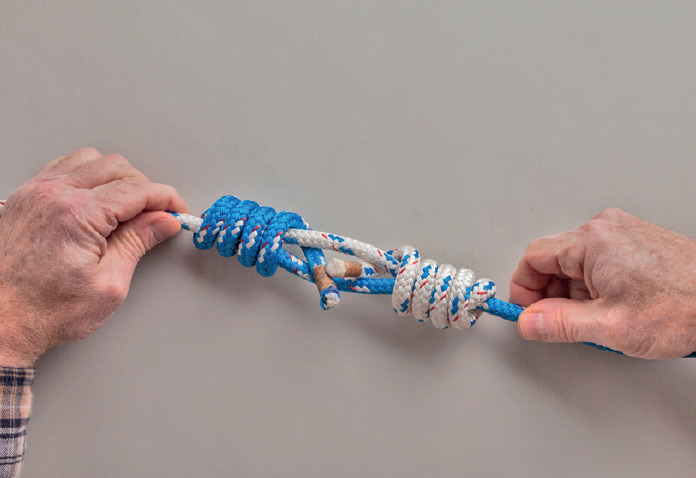

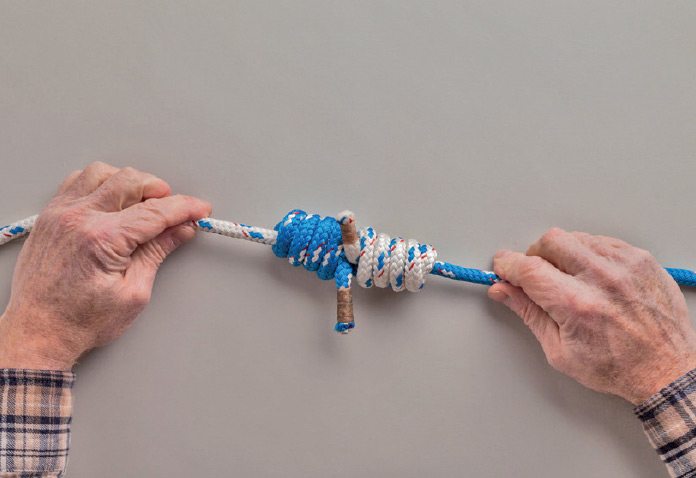

56.

Uses: joining cordage of any weight, including monofilament and anchor lines

Pros: easy to tie, quite secure

Cons: difficult to untie

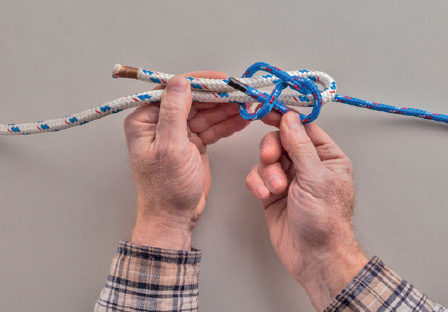

57.

Uses: joining ends of rope of any weight, especially monofilament

Pros: very secure, simple in concept

Cons: difficult to manipulate, very difficult to untie