Книга: Английский язык. Практический курс для решения бизнес-задач

Назад: Wages and Spending

Дальше: Active Fiscal Policy

Excessive Saving

To Keynes, excessive saving, i.e. saving beyond planned investment, was a serious problem encouraging recession, even depression. Excessive saving results if investment falls due to falling consumer demand, over-investment in earlier years, or pessimistic business expectations, and if saving does not immediately fall in step.

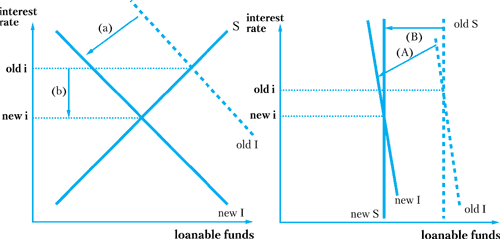

The classical economists argued that interest rates would fall due to the excess supply of «loanable funds». The first diagram from The General Theory shows this process. Assume that fixed investment in plant and equipment falls from «old I» to «new I» (step a). Step b: the resulting excess of saving causes interest-rate cuts, abolishing the excess supply: so again we have saving (S) equal to investment. The interest-rate fall prevents that of production and employment.

Keynes argued against this laissez faire response. The graph shows his argument, assuming again that fixed investment falls (step A). First, saving does not fall much as interest rates fall, since the income and substitution effects of falling rates go in conflicting directions. Second, since planned investment in plant and equipment is mostly based on long-term expectations of future profitability, that spending does not rise much as interest rates fall. So S and I are drawn as inelastic in the graph.

Given the inelasticity of both demand and supply, a large interest-rate fall is needed to close the saving/investment gap. As drawn, this requires a negative interest rate at equilibrium (where the new I line would intersect the old S line). However, this negative interest rate is not necessary to Keynes’s argument.

Third, Keynes argued that saving and investment are not the main determinants of interest rates. Instead, the supply of and the demand for money determine interest rates in the short run. Neither change quickly in response to excessive saving to allow fast interest-rate adjustment.

Finally, because of fear of capital losses on assets besides money, Keynes suggested that there might be a «liquidity trap» setting a floor under which interest rates cannot fall. (In this trap, bond holders, fearing rises in interest rates (because rates are so low), fear capital losses on their bonds and thus try to sell them to attain money (liquidity).) Even economists who reject this liquidity trap now realize that nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero. The equilibrium suggested by the new I line and the old S line cannot be reached, so that excess saving persists.

Even if this «trap» does not exist, there is a fourth element to Keynes’s critique. Saving involves not spending all of one’s income. It means insufficient demand for business output, unless it is balanced by other sources of demand. Thus, excessive saving corresponds to an unwanted accumulation of inventories. This pile-up of unsold goods and materials encourages businesses to decrease both production and employment. This in turn lowers people’s incomes – and saving, causing a leftward shift in the S line in the diagram. For Keynes, the fall in income did most of the job ending excessive saving and allowing the loanable funds market to attain equilibrium. Instead of interest-rate adjustment solving the problem, a recession does so.

Whereas the classical economists assumed that the level of output and income was constant at any one time (except for short-lived deviations), Keynes saw this as the key variable that adjusted to equate saving and investment.

Finally, a recession undermines the business incentive to engage in fixed investment. With falling incomes and demand for products, the desired demand for factories and equipment (not to mention housing) will fall. This accelerator effect would shift the I line to the left again. This recreates the problem of excessive saving and encourages the recession to continue.

Назад: Wages and Spending

Дальше: Active Fiscal Policy