Книга: Английский язык. Практический курс для решения бизнес-задач

Назад: Porter’s Five Forces

Дальше: Essential Vocabulary

Porter’s 5 Forces

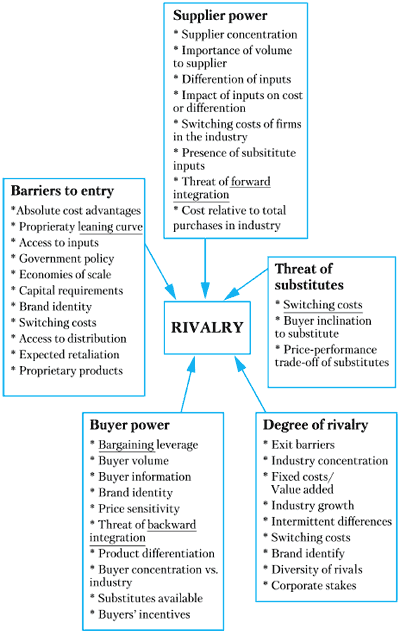

I. Rivalry

In the traditional economic model, competition among rival firms drives profits to zero. But competition is not perfect and firms are not unsophisticated passive price takers. They strive for a competitive advantage over their rivals.

Economists measure rivalry by indicators of industry concentration. The Concentration Ratio (CR) is one such measure. The Bureau of Census periodically reports the CR for major Standard Industrial Classifications (SIC). The CR indicates the percent of market share held by the four largest firms. A high concentration ratio indicates that the industry is concentrated. With only a few firms holding a large market share, the competitive landscape is closer to a monopoly. A low concentration ratio indicates that the industry is characterized by many rivals, none of which has a significant market share. These fragmented markets are competitive.

If rivalry among firms in an industry is low, the industry is considered to be disciplined. This discipline may result from the industry’s history of competition, the role of a leading firm, or informal compliance with a generally understood code of conduct. Explicit collusion generally is illegal; in low-rivalry industries competitive moves must be constrained informally. However, a maverick firm seeking a competitive advantage can displace the otherwise disciplined market.

When a rival acts in a way that elicits a counter-response by other firms, rivalry intensifies. The intensity of competition is referred to as being cutthroat, intense, moderate, or weak, based on the firms’ aggressiveness in gaining an advantage.

A firm can choose from several competitive moves:

– Price competition.

– Improving product differentiation.

– Creatively using channels of distribution, such as vertical integration.

– Exploiting relationships with suppliers.

The intensity of rivalry is influenced by the following industry characteristics:

– A larger number of firms increases rivalry because more firms must compete for the same customers and resources. The rivalry intensifies if the firms have similar market share, leading to a struggle for market leadership.

– Slow market growth causes firms to fight for market share. In a growing market, firms are able to improve revenues simply because of the expanding market.

– High fixed costs result in an economy of scale that increases rivalry. When total costs are mostly fixed costs, the firm must produce near capacity to attain the lowest unit costs. Since the firm must sell this large quantity of product, high levels of production lead to a fight for market share and result in increased rivalry. High storage costs cause a producer to sell goods as soon as possible. If other producers are attempting to unload at the same time, competition for customers intensifies.

– Low switching costs increase rivalry. When a customer can freely switch from one product to another there is a greater struggle to capture customers.

– Low levels of product differentiation are associated with higher levels of rivalry. Brand identification, on the other hand, tends to constrain rivalry.

– Strategic stakes are high when a firm is losing market position or has potential for great gains. This intensifies rivalry.

– High exit barriers place a high cost on abandoning the product. High exit barriers cause a firm to remain in an industry, even when the venture is not profitable.

– When the plant and equipment required for manufacturing a product are highly specialized, these assets cannot easily be sold to other buyers in another industry.

– A diversity of rivals with different cultures, and philosophies makes an industry unstable. There is greater possibility for mavericks and for misjudging rival’s moves.

– A growing market and the potential for high profits induce new firms to enter a market and incumbent firms to increase production. A point is reached where the industry becomes crowded with competitors, and demand cannot support the new entrants and the resulting increased supply. A shakeout ensues, with intense competition, price wars, and company failures.

– BCG founder Bruce Henderson generalized this observation as the Rule of Three and Four: a stable market will not have more than three significant competitors, and the largest competitor will have no more than four times the market share of the smallest. It implies that:

– If there is a larger number of competitors, a shakeout is inevitable.

– Surviving rivals will have to grow faster than the market.

– Eventual losers will have a negative cash flow if they attempt to grow.

– All except the two largest rivals will be losers.

II. Threat of Substitutes

In Porter’s model, substitute products refer to products in other industries. A threat of substitutes exists when a product’s demand is affected by the price change of a substitute product. A product’s price elasticity is affected by substitute products – as more substitutes become available, the demand becomes more elastic since customers have more alternatives. A close substitute product constrains the ability of firms in an industry to raise prices. The competition engendered by a Threat of Substitutes comes from products outside the industry.

III. Buyer Power

The power of buyers is the impact that customers have on a producing industry.

When buyer power is strong, the relationship to the producing industry is near to a monopsony – a market in which there are many suppliers and one buyer. Under such market conditions, the buyer sets the price. In reality few pure monopsonies exist, but frequently there is some asymmetry between a producing industry and buyers.

IV. Supplier Power

A producing industry requires raw materials – labor, components, and other supplies. This requirement leads to buyer-supplier relationships between the industry and the firms that provide it the raw materials used to create products. Suppliers, if powerful, can exert an influence on the producing industry, such as selling raw materials at a high price to capture some of the industry’s profits.

V. Barriers to Entry / Threat of Entry

It is not only incumbent rivals that pose a threat to firms in an industry; the possibility that new firms may enter the industry also affects competition. In theory, any firm should be able to enter and exit a market, and if free entry and exit exists, then profits always should be nominal. In reality, however, industries possess characteristics that protect the high profit levels of firms in the market and inhibit additional rivals from entering the market. These are barriers to entry.

Barriers to entry are more than the normal equilibrium adjustments that markets typically make. When industry profits increase, we would expect additional firms to enter the market to take advantage of the high profit levels, over time driving down profits for all firms in the industry. When profits decrease, we would expect some firms to exit the market thus restoring a market equilibrium. Falling prices deter rivals from entering a market. Firms also may be reluctant to enter highly uncertain markets, especially if entering involves expensive start-up costs. If firms individually keep prices artificially low as a strategy to prevent potential entrants from entering the market, such entry-deterring pricing establishes a barrier.

Barriers to entry reduce the rate of entry of new firms, thus maintaining a level of profits for those already in the industry. Barriers to entry arise from several sources:

– Government creates barriers.

– Patents and proprietary knowledge serve to restrict entry into an industry.

– Asset specificity inhibits entry into an industry.

– Organizational (Internal) Economies of Scale. The most cost efficient level of production is termed Minimum Efficient Scale (MES). This is the point at which unit costs for production are at minimum.

Barriers to exit work similarly to barriers to entry. Exit barriers limit the ability of a firm to leave the market and can exacerbate rivalry – unable to leave the industry, a firm must compete.

Source:

Назад: Porter’s Five Forces

Дальше: Essential Vocabulary