THE FAIRY TALES OF HERMANN HESSE

The Dwarf

(1904)

One evening down on the quay the old storyteller Cecco began telling the following tale—

If it is all right with you, ladies and gentlemen, I shall tell you a very old story about a beautiful lady, a dwarf, and a love potion, about fidelity and infidelity, love and death, all that is at the heart of every adventure and tale, whether it be old or new.

Signorina Margherita Cadorin, daughter of the nobleman Batista Cadorin, was in her day the most beautiful among all the beautiful women of Venice. The poems and songs dedicated to her were more numerous than the curved bay windows of the palaces on the Grand Canal and more plentiful than the gondolas that swim between the Ponte del Vin and the Ponte della Dogana on a spring evening. Hundreds of young and old lords from Venice and Murano, and just as many from Padua, could not close their eyes for a single night without dreaming about her; nor could they wake up the next morning without yearning for a glimpse of her. Moreover, there were few among the fine young ladies in the entire city who had not been jealous of Margherita Cadorin at one time or another. Since it is impossible for me to describe her, I shall content myself with saying that she was blond, tall, and slender like a young cypress, that her hair flattered the air, and the soles of her feet, the ground, and that Titian, when he saw her, is said to have wished that he could spend an entire year and paint nothing and nobody but this woman.

With regard to clothes, lace, Byzantine gold brocade, precious stones, and jewels, the beautiful signorina lacked nothing. On the contrary, her palace was rich and splendid. The oriental rugs were thick and colorful. The closets contained plenty of silver utensils. The tables glistened with their fine damask and glorious porcelain. The floors of the rooms were filled with beautiful mosaics, and the ceilings and walls were covered partially with Gobelin tapestries made of brocade and silk, and partially with bright and attractive paintings. In addition, there were plenty of gondolas and gondoliers.

Of course, all these expensive and pleasant things could also be found in other houses. There were larger and richer palaces than hers, more abundantly filled closets, more expensive utensils, rugs, and jewels. At that time Venice was very wealthy, but young Margherita possessed a gem all to herself that was the envy of many people richer than she. It was a dwarf by the name of Filippo, a fantastic little fellow, just about three feet tall with two humps on his back. Born in Cyprus, Filippo could speak only Greek and Syrian when Vittoria Battista brought him home one day from a trip. Now, however, he spoke such a pure Venetian dialect that it seemed as if he had been born on the Riva or in the parish of San Giobbe. As beautiful and slender as his mistress was, the dwarf was just that ugly. If she stood next to his crippled figure, she appeared doubly tall and majestic, like the tower of an island church next to a fisherman’s hut. The dwarf’s hands were wrinkled, brown, and bent at the joints. His gait was unspeakably ridiculous; his nose, much too large; his feet, wide and pigeon-toed. Yet when dressed, he walked like a prince garbed in pure silk and gold.

Just this outward appearance made the dwarf a gem. It was perhaps impossible to find anyone who cut a figure stranger and more comical, not only in Venice but in all of Italy, including Milan. And many a royal king, prince, or duke would certainly have been glad to pay gold for the little man, if he had been for sale.

Now there may have indeed been dwarfs just as small and ugly as Filippo at certain courts or in rich cities, but he was far superior to them with regard to brains and talent. If everything depended on intelligence alone, then this dwarf could easily have had a seat on the Council of Ten or been head of an embassy. Not only did he speak three languages, but he also had a great command of history and was clever at inventing things. He was just as good at telling old stories as he was at creating new ones, and he knew how to give advice, play mean tricks, and make people laugh or cry, if he so desired.

On pleasant days, when Margherita sat on her balcony to bleach her wonderful hair in the sun, as was generally the fashion at that time, she was always accompanied by her two chambermaids, her African parrot, and the dwarf Filippo. The chambermaids moistened and combed her long hair and spread it over a large straw hat to bleach it. They sprayed it with the perfume of roses and Greek water, and while they did this, they told her about everything that was happening or about to happen in the city: the deaths, the celebrations, the weddings, births, thefts, and funny incidents. The parrot flapped its beautifully colored wings and performed its three tricks: It whistled a song, bleated like a goat, and cried out, “Good night!” The dwarf sat there, squatting motionless in the sun, and read old books and scrolls, paying very little attention to the gossip of the maids or to the swarming mosquitoes. Then on each of these occasions, after some time had passed, the colorful bird would nod, yawn, and fall asleep; the maids would chatter ever more slowly and gradually turn silent and finish their chores quietly with tired gestures, for is there a place where the noon sun burns hotter or makes one drowsier than on the balcony of a Venetian palace? Yet the mistress would become sullen and give the maids a good scolding if they let her hair become too dry or touched it too clumsily. Finally the moment would arrive when she cried out, “Take the book away from him!”

The maids would take the book from Filippo’s knees, and the dwarf would look up angrily, but he would also manage to control himself at the same time and ask politely what his mistress desired.

And she would command, “Tell me a story!”

Whereupon the dwarf would respond, “I need to think for a moment,” and he would reflect.

Sometimes he would take too much time, so that she would yell and reprimand him. However, he would calmly shake his heavy head, which was much too large for his body, and answer with composure, “You must be patient a little while longer. Good stories are like those noble wild animals that make their home in hidden spots, and you must often settle down at the entrance of the caves and woods and lie in wait for them a long time. Let me think!”

When he had thought enough and began telling his story, however, he let it all flow smoothly until the end, like a river streaming down a mountain in which everything is reflected, from the small green grass to the blue vault of the heavens. The parrot would sleep and dream, at times snoring with his crooked beak. The small canals would lie motionless so that the reflections of the houses stood still like real walls. The sun would burn down on the flat roof, and the maids would fight desperately against their drowsiness. But the dwarf would not succumb to sleep. Instead, as soon as he exhibited his art, he would become a king. Indeed, he would extinguish the sun and soon lead his transfixed mistress through dark, terrifying woods, then to the cool blue bottom of the sea, and finally through the streets of exotic and fabulous cities, for he had learned the art of storytelling in the Orient, where storytellers are highly regarded. Indeed, they are magicians and play with the souls of their listeners as a child plays with his ball.

His stories rarely began in foreign countries, for the minds of listeners cannot easily fly there on their own powers. Rather, he always began with things that people can see with their own eyes, whether it be a golden clasp or a silk garment. He always began with something close and contemporary. Then he led the imagination of his mistress imperceptibly wherever he wanted, talking first about the people who had previously owned some particular jewels or about the makers and sellers of the jewels. The story floated naturally and slowly from the balcony of the palace into the boat of the trader and drifted from the boat into the harbor and onto the ship and to the farthest spot of the world. It did not matter who his listeners were. They would all actually imagine themselves on this voyage, and while they sat quietly in Venice, their minds would wander about serenely or anxiously on distant seas and in fabulous regions. Such was the way that Filippo told his stories.

Aside from reciting wonderful fairy tales mostly from the Orient, he also gave reports about real adventures and events from the past and present, about the journeys and misfortunes of King Aeneas, about rich Cyprus, about King John, about the magician Virgilius, and about the impressive voyages of Amerigo Vespucci. On top of everything, he himself knew how to invent and convey the most remarkable stories. One day, as his mistress glanced at the slumbering parrot, she asked, “Tell me, oh Know-It-All, what is my parrot dreaming about now?”

The dwarf thought for a moment and then related a long dream as if he himself were the parrot. As soon as he was finished, the bird woke up, bleated like a goat, and flapped its wings. Another time the lady took a small stone, threw it over the railing of the terrace into the canal, where it splashed into the water, and asked, “Now, Filippo, where is my stone going?”

Immediately the dwarf related how the stone in the water drifted down to the jellyfish, crabs, oysters, and fish, to the drowned fishermen and water spirits, imps and mermaids, whose lives and experiences he knew quite well and could describe in precise detail.

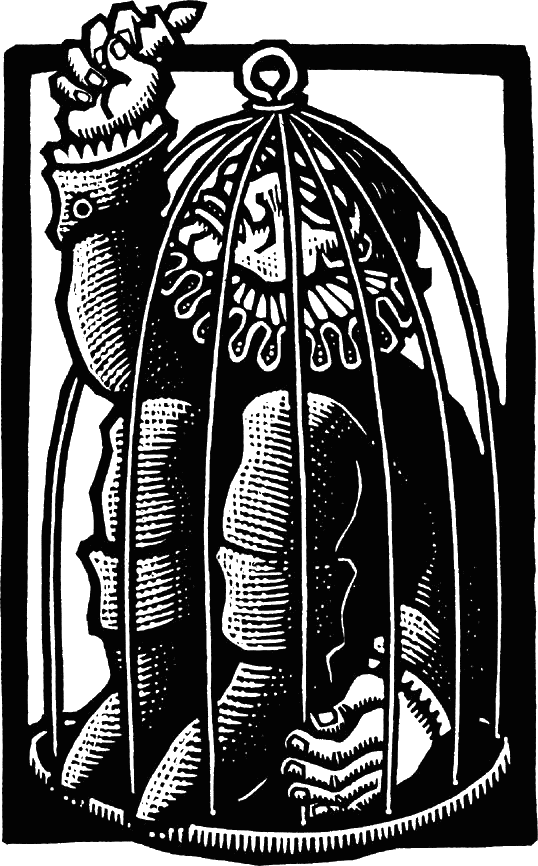

Even though Signorina Margherita, like many other rich and beautiful women, was arrogant and cold, she had great affection for her dwarf and made certain that everyone treated him nicely and honorably. Yet there were times when she herself took pleasure in tormenting him a little. After all, he was her property. Sometimes she took all his books away or locked him in the cage of her parrot. Other times she would make him stumble and trip on the floor of a large hall. Since she did not do this out of meanness, Filippo never complained, but he also never forgot a thing, and sometimes he wove little allusions, hints, and insinuations in his fables and fairy tales, which his mistress tolerated with composure. She took care not to irritate him too much, for everyone believed that the dwarf possessed secret knowledge and forbidden powers. People were certain that he knew how to talk with many kinds of animals and that his predictions about the weather and storms were always correct. He kept silent for the most part, however, and if people bothered him with questions, he would shrug his sharp shoulders and try to shake his stiff head, and the questioners would soon forget their business out of pure laughter.

Just as every human being has a need to be attached to some living soul and to show love, Filippo was also attached, and it was not just to his books. Rather, he had a strange friendship with a small black dog that belonged to him and slept with him. It had been given to Signorina Margherita as a gift by one of her rejected suitors and had been passed on to the dwarf by his mistress under most unusual circumstances. On the very first day that the dog arrived, it had an unfortunate accident and was struck by a closing trap door. The dog had broken a leg and was supposed to be put to death. But the dwarf interceded on its behalf and received the animal as a gift. Under his care the dog recovered and, out of great gratitude, became deeply attached to its savior. Nevertheless, the healed leg remained crooked so that the dog limped and was thus even better suited to its malformed master. Consequently, Filippo was to hear many a joke about this.

Though this love between dwarf and dog seemed ridiculous to many people, it was no less sincere and warm for all that, and I believe that not many a rich lord was as deeply loved by his best friends as this bow-legged miniature hound was by Filippo, who named the dog Filippino and then shortened it to the pet name Fino. Indeed, he treated the dog as tenderly as a child, talked to him, brought him delicious treats, let him sleep in his little dwarf bed, and frequently played with him for a long time. In short, he transferred all the love of his poor and homeless life to the clever animal and was mocked for it a great deal by the servants and his mistress. But as you will soon see, this affection for the dog was not ridiculous at all. In fact, it led to a great disaster, not only for the dog and the dwarf but also for the entire house. So I hope that you are not annoyed by my talking too much about this small lame lapdog. As you well know, small things in life often cause the greatest catastrophes.

While many distinguished, rich, and handsome men cast their eyes on Margherita and carried her picture in their hearts, she herself remained so proud and cold, it was as if men did not exist. Indeed, until the death of her mother, a certain Donna Maria from the House of the Giustiniani, she had been raised in a very strict and rigid way. Moreover, she was born with a supercilious nature that was opposed to love, and she was justifiably regarded as not only the most beautiful woman of Venice but the most cruel. A young nobleman from Padua was killed in a duel with an officer from Milan on her account, and when she was told that the dead man’s last words were intended for her, it was impossible to detect even the slightest shadow on her white forehead. She continually mocked all the sonnets dedicated to her. When two suitors from the most respectable families of the city ceremoniously asked for her hand at almost the same time, she compelled her father to reject them, in spite of the fact that her father was in favor of her marrying either of the men. A prolonged family dispute resulted from this affair.

But the tiny winged god of love is a cunning rascal and does not like to lose his prey, especially such a beautiful one. Now as we know from experience, proud and unapproachable women are precisely the ones who fall in love the fastest and with the most passion, just as the warmest and most glorious spring usually follows the hardest winter. So it was with Margherita, who lost her heart to a young cavalier and seafarer during a celebration in the Muranese gardens. He had just returned from the Levant, and his name was Baldassare Morosini. He soon caught Margherita’s attention, and it was apparent that he was just as noble and majestic as she was. Whereas she was light and slender, he was dark and strong, and one could see that he had been on the seas and abroad for a long time and was disposed toward adventure. His thoughts flickered over his tan brow like lightning, and his dark eyes burned intensely and sharply over his aquiline nose.

It was impossible for him not to notice Margherita, and once he learned her name, he immediately arranged to be introduced to her and her father. And indeed, all this transpired with many flattering words and polite gestures. Then he stayed as close to her as propriety allowed until the end of the party, which lasted until midnight, and she listened to his words more eagerly than to the gospel, even when they were addressed to other people and not herself. As you may imagine, Baldassare was asked more about his voyages, deeds, and constant dangers than anything else, and he spoke of them with such decorum and serenity that everyone took great pleasure in listening to him. In reality all his stories were dedicated to one listener only, and she did not let one breath of his words escape her. With such ease did he talk about the strangest adventures that his listeners were led to believe they themselves must have actually experienced them. Nor did he place himself too much in the foreground, as seafarers, especially young ones, are won’t to do. Only one time, when he was recounting a battle with African pirates, did he mention a wound — its scar ran diagonally across his left shoulder — and Margherita held her breath as she listened, fascinated and horrified at the same time.

At the end of the party he accompanied her and her father to their gondola, bade them farewell, and remained standing for a long time, gazing at the torch of the gondola as it glided over the dark lagoon. Only after he completely lost sight of the gondola did he return to his friends in the arbor of a tavern, where the young cavaliers, and also some pretty maids, spent the rest of the warm night drinking yellow Greek wine and sweet red. Among them was Giambattista Gentarini, one of the richest young men of Venice, who enjoyed life to the hilt. He approached Baldassare, touched his arm, and said with a laugh, “I had really hoped that you would tell us tonight about your amorous affairs during your voyages! Now there’s probably no chance of this since the beautiful Cadorin has stolen your heart. But you better know that this beautiful lady is made of stone and has no soul. She’s like one of Giorgione’s paintings. Though you truly can’t find much fault with his women, they’re not made out of flesh and blood. They exist only for our eyes. Seriously, I advise you to keep away from her — or would you like to become the laughingstock of the Cadorinian family and the third to be rejected?”

In response, Baldassare only laughed and did not feel compelled to justify his actions. He emptied a couple of glasses of the sweet, oil-colored Cyprian wine and went home earlier than his friends.

The very next day at the proper hour, he visited old Signore Cadorin in his small pretty palace and sought as best he could to make himself acceptable and to win the father’s favor. In the evening he serenaded Margherita with many singers and musicians and had some success — she stood listening at the window and even appeared for a short time on the balcony. Naturally, the entire city began talking about this right away, and the idlers and scandal-mongers knew of the engagement and the supposed day of the wedding even before Morosini put on his best suit to ask Margherita’s father for her hand. In fact, he spurned the custom of that time, and instead of sending one or two of his friends to present his case, he appeared himself before the father. Soon enough, however, the gossips, who always know it all, could take pleasure in seeing their predictions confirmed.

When Baldassare went to Margherita’s father and expressed his wish to become his son-in-law, Cadorin was, to say the least, most embarrassed.

“By almighty God, my dear young man,” he said imploringly, “I don’t underestimate the honor that your proposal means for my family. Nevertheless, I beg you not to proceed with your plans. It would spare you and me much grief and trouble. You’ve been away from Venice a long time on voyages, so you don’t know how many problems this unfortunate girl has caused me. Indeed, she has recently rejected two honorable proposals without any reason whatsoever. She doesn’t care about love and men. And I confess that I have spoiled her somewhat and am too weak to be severe with her and break her stubbornness.”

Baldassare listened politely, but he did not retract his proposal. On the contrary, he took great pains to soothe the anxious old man and put him in a more cheerful mood. Finally, Signore Cadorin promised to speak to his daughter.

You can surely imagine how the lady responded. To be sure, she raised some minor objections and put on quite a show of arrogance in front of her father, but in her heart she had said yes even before she was asked. Immediately after he received her answer, Baldassare appeared with a delicate and valuable gift, placed a gold wedding ring on the finger of his fiancée, and kissed her beautiful proud lips for the first time.

Now the Venetians had something to gaze at, to talk about, and to envy. No one could remember ever seeing such a magnificent couple. Both were tall and had fine figures. The young lady was barely a hair’s breadth smaller than he was. She was blond; he was dark; and both held their heads high and free. Indeed, when it came to a noble and superior bearing, they could compete with the best.

But one thing did not please the splendid bride, and it occurred when Baldassare told her that he would soon have to travel to Cyprus again in order to conclude some important business. The wedding was to take place upon his return. The entire city was looking forward to it already, as though it were a public celebration. In the meantime the couple enjoyed their happiness without much disturbance. Baldassare missed no opportunity to organize events for her, to give her gifts, to serenade her, and to bring about surprises, and he was with Margherita as often as possible. They even took some discreet rides together in a covered gondola, though this was strictly forbidden.

If Margherita was supercilious and a little bit cruel, it was not surprising given the fact that she was a spoiled young aristocratic lady. She was matched, however, by her bridegroom, who was basically arrogant and not used to being considerate toward others. Nor had his work as a sea merchant and his early successes in life made him any gentler. Though he had courted Margherita arduously as a pleasant and demure young man, his true character and ambitions surfaced only after he had attained his goal. Naturally impulsive and overbearing, as seafarer and rich merchant he had become completely accustomed to fulfilling his own desires and to not caring about other people. Right from the beginning it was strange how repulsive he found many of the things that surrounded his bride, especially the parrot, the little dog Fino, and the dwarf Filippo. Whenever he saw these three, he became irritated and did everything he could to torture them or to get them away from their mistress. And whenever he entered the house and his strong voice could be heard on the winding stairs, the little dog howled and fled and the parrot cried and flapped its wings. The dwarf contented himself with withdrawing and remaining stubbornly quiet. To be just, I must say that Margherita put in many a good word, if not for the animals then certainly for Filippo, and she sometimes tried to defend the poor dwarf. Of course, she did not dare to offend her lover and could not or would not prevent many small torturous and cruel acts.

In the case of the parrot, its life came to a quick end. One day as Signore Morosini was tormenting it by picking at it with his small cane, the enraged bird pecked his hand with its strong and sharp beak until a finger bled. In response, Morosini had the bird strangled and thrown into the narrow dark canal in back of the house, and nobody mourned it.

Soon after this, things did not go much better for the little dog Fino. Whenever the bridegroom entered Margherita’s house, the dog hid in a dark corner of the stairs, as it had learned not to be seen when it heard the sound of this man’s footsteps. But one time — when perhaps Baldassare had forgotten something in his gondola and did not trust any of his servants to fetch it — he turned around at the top of a flight and walked unexpectedly down the stairs. The frightened Fino barked loudly in his surprise and jumped about so frantically and clumsily that he almost caused the signore to fall. Baldassare stumbled and reached the corridor floor at the same time that the dog did, and since the frightened little animal scrambled right up to the entrance, where some wide stone steps led into the canal, Baldassare gave him a violent kick along with some harsh curses. As a result, the little dog was propelled far out into the water.

Just at this moment the dwarf appeared in the doorway. He had heard Fino’s barking and whimpering, and now he stood next to Baldassare, who looked on with laughter as the little lame dog tried anxiously to swim. At the same time the noise drew Margherita to the balcony of the first floor.

“Send the gondola over to him, for God’s sake!” Filippo yelled to her breathlessly. “Mistress, have him fetched right away! He’s going to drown! Oh Fino, Fino!”

But Baldassare laughed and commanded the gondolier, who was about to untie the gondola, to stop. Again Filippo turned to his mistress to beg her, but Margherita left the balcony just at that moment without saying a word. So the dwarf knelt down before his tormentor and implored him to let the dog live. The signore refused and turned away from him. Then with severity he ordered the dwarf to go back into the house. He himself remained on the steps of the gondola until the small gasping Fino sank beneath the water.

Filippo climbed to the top floor beneath the roof, where he sat in a corner, held his large head in his hands, and stared straight ahead. A chambermaid came to summon him to his mistress, followed by a servant. But the dwarf did not move. Later in the evening, while he was still sitting up there, his mistress herself climbed up to him with a light in her hand. She stood before him and looked at him awhile.

“Why don’t you get up?” she finally asked. He did not answer. “Why don’t you get up?” she asked again.

Then the stunted little man looked at her and said, “Why did you kill my dog?”

“It wasn’t me who did it,” she sought to justify herself.

“You could have saved him, but you let him die,” the dwarf accused. “Oh my darling! Oh Fino, oh Fino!”

Then Margherita became irritated and impatiently ordered him to get up and go to bed. He obeyed her without saying a word and remained silent for three days like a dead man. He hardly ate his meals and paid no attention to anything that happened around him or that was said.

During these days the young signorina became greatly troubled. In fact, she had heard from different sources certain things about her fiancé that upset her to no end. It was said that the Signore Morosini had been a terrible philanderer on his journeys and had numerous mistresses on the island of Cyprus and in other places. Since this was really the truth, Margherita became filled with doubt and fears and contemplated Baldassare’s forthcoming voyage with bitter sighs. Finally she could stand it no longer. One morning when Baldassare was in her house, she told him everything she knew and did not conceal the least of her fears.

He smiled and said, “What they have told you, my dearest and most beautiful lady, may be partly false, but most of it is true. Love is like a wave. It comes, lifts us up high, and sweeps us away without our being able to resist it. Nevertheless, I’m fully aware of what I owe my bride and the daughter of such a noble house. Therefore you need not fret. I have seen many a beautiful woman here and there and have fallen in love with many, but there is none who can compare to you.”

And because a magic emanated from his strength and boldness, she calmed down, smiled, and stroked his hard brown hand. But as soon as he left, all her fears returned to haunt her. As a result, this extremely proud lady now experienced the secret, humiliating pain of love and jealousy and lay awake every night for half the night in her silken sheets.

In her distress she turned once again to her dwarf Filippo, who meanwhile had regained his composure and acted as if he had forgotten the disgraceful death of his little dog. He sat on the balcony as he had before, reading books or telling stories, while Margherita bleached her hair in the sun. Only one time did she specifically recall that incident, and that was when she asked him why he was so deeply buried in his thoughts, and he replied in a strange voice, “God bless this house, most gracious mistress, that I shall soon leave dead or alive.”

“Why?” she responded.

Then he shrugged his shoulders in his ridiculous way and said, “I sense it, mistress. The bird is gone. The dog is gone. What reason does the dwarf have for staying here?”

Thereupon she seriously forbade him ever to talk like that again, and he did not speak about it anymore. Indeed, the lady became convinced that he no longer thought about it, and she once again had complete trust in him. Whenever she talked to him about her concerns, he defended Signor Baldassare and did not reveal in any way that he held anything against the young cavalier. Consequently the dwarf regained the full friendship of his mistress.

One summer evening, as a cool wind was sweeping in from the sea, Margherita climbed into her gondola along with the dwarf and had herself rowed out into the open sea. When the gondola came near Murano, the city was swimming like a white image of a dream in the distance on the smooth, glittering lagoon. She commanded Filippo to tell a story, while she lay stretched out on the black cushion. The dwarf crouched across from her on the bottom of the gondola, his back turned toward the high bow of the vessel. The sun hung on the edge of the distant mountains, which could hardly be seen through the rosy haze. Some bells began to ring on the island of Murano. The gondolier, numb from the heat and half asleep, sluggishly moved his long rudder, and along with the rudder, his bent figure was reflected in the water laced with seaweed. Sometimes a freight barge sailed close by, or a fishing boat with a lateen sail, whose pointed triangle momentarily concealed the distant towers of the city.

“Tell me a story!” commanded Margherita, and Filippo bent his heavy head, played with the gold fringes of his silk dress-coat, deliberated a while, and told the following tale:

“During the time my father lived in Constantinople, long before I was born, he experienced something most remarkable and unusual. At that time he was a practicing doctor and consultant in difficult cases, having learned the science of medicine and magic from a Persian who lived in Smyrna and had gained a great deal of knowledge in both fields. My father was an honest man and depended not on deception or flattery but only on his art. Nevertheless, he suffered from the envy and slander of many a swindler and quack. So he kept yearning for an opportunity to return to his homeland. On the other hand, my father did not want to travel home until he had amassed at least a small fortune, for he knew his family and relatives were languishing in poverty at home. Although he witnessed numerous deceivers and incompetent doctors grow rich without effort, he himself did not enjoy any luck. Consequently he became more and more despondent and almost gave up hope of achieving success without tricking people. Although he did in fact have many clients and had helped hundreds of people in very difficult situations, they were mostly the poor and humble, and he would have felt ashamed to accept more than a small token from them for his services.

“As a result of this miserable predicament, my father determined it was best to leave the city. He planned either to leave on foot without any money or to offer his services on board a ship. He made up his mind to wait one more month, however, because judging from the astrological charts, it seemed still possible that he might encounter some luck within this time period. Yet the month passed without anything fortunate occurring. So on the last day, he sadly packed up his meager possessions and got ready to depart the next morning.

“On the evening of the last day he wandered back and forth along the beach outside the city, and you can certainly imagine how dreary his thoughts were. The sun had long since set, and the stars were already spreading their white light over the calm sea.

“Suddenly my father heard a doleful sobbing very near him. He looked all around, but since he could see no one, he became terribly afraid, as he believed that this was an evil omen regarding his departure. When the moaning was repeated even louder, however, he took courage and called out, ‘Who’s there?’ Immediately he heard a splashing on the bank of the sea, and when he turned in that direction, he saw a bright figure lying there in the pale glimmer of the stars. Thinking that it was a shipwrecked person or a swimmer, he went over to help and saw, to his astonishment, the most beautiful, slender mermaid, white as snow, projecting half her body out of the water. Who can describe his surprise when the nymph spoke to him in an imploring voice. ‘Aren’t you the Greek magician who lives on Yellow Alley?’

“ ‘That’s me,’ he answered in a most friendly way. ‘What do you want from me?’

“Once more the young mermaid began to moan, stretched out her beautiful arms, and implored my father with many sobs to take pity on her and prepare a strong love potion for her because she was pining away in futile desire for her lover. She looked at him with such beautiful eyes, pleading and sad, that his heart was moved, and he decided right then and there to help her. Before he did anything, however, he asked her how she intended to reward him, and she promised him a chain of pearls so long that a woman would be able to sling it around her neck eight times. ‘But you will not receive this treasure,’ she continued, ‘until I have seen that your magic has done its job.’

“My father did not have to worry about this, for he was certain of the power of his art. He rushed back into the city, opened up his neatly packed bundle, and prepared the desired love potion with such speed that by midnight he was back at the bank of the sea, where the mermaid was waiting for him. He handed her a tiny vial filled with the precious liquid. Then she thanked him with great emotion and told him to return to the same spot the following night in order to receive the rich reward that she had promised.

“He went away and spent the night and the next day in great expectation. Though he had not the slightest doubt about the power and effect of his potion, he was not sure whether he could depend on the word of the mermaid. With such thoughts he proceeded to the same place at nightfall. He did not have to wait long until the mermaid appeared out of the nearby waves. But my father was overcome with horror when he saw what he had helped bring about with his art. As she drew closer with a smile on her lips and extended toward him the heavy pearl chain in her right hand, he saw the corpse of an extraordinarily handsome young man in her left arm. He could tell from his clothes that the man was a Greek sailor. His face was as pale as death, and the locks of his hair swam on the waves. The mermaid caressed him tenderly and rocked him in her arms as though he were a little boy.

“As soon as my father saw this, he uttered a loud cry and cursed himself and his art, whereupon the mermaid suddenly sank into the water with her lover. The chain of pearls lay on the sand, and since he could not undo the harm that he had caused, he picked up the necklace and carried it under his coat to his dwelling, where he separated the pearls in order to sell them one by one. By the time he left for Cyprus aboardship, he had plenty of money and believed that he would never have to worry about poverty again. But the blood of an innocent man had tarnished the money, and it caused him one misfortune after another. Indeed, he was robbed of his possessions by storms and pirates and did not reach his homeland until two years later, as a shipwrecked beggar.”

During the telling of this entire story, the dwarf’s mistress listened with rapt attention. When Filippo finished and was silent, she did not utter a single word and remained deeply absorbed in her thoughts until the gondolier stopped and waited for the command to return home. All at once she jumped, as if startled by a dream, and signaled the gondolier to return. As she drew the curtains together to conceal herself, the rudder altered their course quickly, and the gondola flew like a black bird toward the city. The dwarf still crouched on the floor and looked calmly and seriously over the dark lagoon as if he were already thinking up another new story. Soon they arrived at the city, and the gondola sped home through the Rio Panada and the other small canals.

That night Margherita had difficulty sleeping. The story about the love potion had given her the idea — just as the dwarf had envisioned — to use the same means to capture the heart of her fiancé completely and secure his love. The next day she began to talk to Filippo about this, but not directly. Rather, she asked him all kinds of questions and was curious about how such a love potion was made, even though the preparation of its secret ingredients was no longer commonly known. She asked him whether the potion contained poisonous and harmful liquids and whether its taste was such that the drinker would suspect something. The clever Filippo answered all these questions with a certain indifference and acted as though he did not notice anything of the secret wishes of his mistress, so that she had to speak even more explicitly about her desires and finally had to ask him directly whether there was someone in Venice who was capable of making such a potion.

Then the dwarf laughed and exclaimed, “You don’t trust my skills very much if you think that I didn’t learn such simple beginning steps of magic from my father, who was such a great wise man.”

“You can actually make such a love potion?” the lady cried with pleasure.

“There’s nothing to it,” responded Filippo. “But I don’t understand why you should need my art when all your wishes have been fulfilled and you have one of the most handsome and richest of men as your fiancé.”

But the beautiful lady continued to insist, so that he eventually proceeded to prepare a potion while pretending to resist. She gave the dwarf money to acquire the necessary herbs and secret ingredients, and she promised him a stately gift later on if everything succeeded.

After two days he finished his preparations and carried the magic potion in a small glass bottle to the table of his mistress. Since Signore Baldassare was to depart for Cyprus soon, the matter was urgent. So when Baldassare proposed a secret pleasure trip to his bride on one of the following days — nobody took walks, due to the heat, during this time of the year — it seemed to Margherita, as well as to the dwarf, the fitting occasion to test the potion.

When Baldassare’s gondola arrived at the appointed hour before the gate of the house, Margherita stood ready, and she had Filippo with her. He carried a bottle of wine and a basket of peaches into the boat, and after his mistress and Signore Baldassare climbed in, he proceeded to take his place in the gondola, sitting at the feet of the gondolier. Baldassare was not pleased that Filippo was accompanying them, but he restrained himself and said nothing. He thought it better to yield to the wishes of his beloved in these final days before his departure.

The gondolier pushed off. Baldassare pulled the curtains tightly together and dined with his bride in the cabin. The dwarf sat calmly in the stern of the gondola and regarded the old high, dark houses of the Rio dei Barardi as the gondolier navigated his vessel until it reached the lagoon at the end of the Grand Canal at the old Palace Giustiniani, where there was still a small garden in those days. Today the beautiful Palace Barozzi stands there, as everyone knows.

Occasionally muffled laughter, the soft noise of a kiss, or part of a conversation could be heard coming from the cabin. Filippo was not curious. He looked out over the water toward the sunny Riva, then at the slender tower of San Giorgio Maggiore, then back at the lion pillar of the Piazzelta. At times he blinked at the hardworking gondolier or splashed the water with a twig that he had found in the bottom of the gondola. His face was as ugly and impassive as always and revealed nothing about his thoughts. Just then he was thinking about his drowned puppy Fino and the strangled parrot. He brooded on how close destruction always was to all creatures, animals as well as humans, and he realized that there is nothing we can predict or know for certain in this world except death. He thought about his father and his homeland and his entire life. His face turned scornful for a moment when he considered that wise people serve fools almost everywhere and that the lives of most people are similar to a bad comedy. He smiled as he looked at his rich silk clothes.

And while he sat there silently with a smile, everything happened that he had been waiting for all along. Baldassare’s voice rang out from beneath the roof of the gondola, and right after that Margherita called out, “Where did you put the wine and the cup, Filippo?”

Signore Baldassare was thirsty, and it was now time to bring him the potion with the wine. So the dwarf opened his small blue bottle, poured the liquid into a cup, then filled it with red wine. Margherita opened the curtains, and the dwarf offered the lady peaches and the bridegroom the wine. She threw him a questioning glance or two and seemed edgy.

Signore Baldassare lifted the cup to his lips, but he cast a glance at the dwarf standing in front of him and was suddenly filled with suspicion.

“Wait a second!” he cried. “Scoundrels like you are never to be trusted. Before I drink, I want you to taste the wine first.”

Filippo did not change his expression. “The wine is good,” he said politely.

But Baldassare remained suspicious. “Well, why don’t you drink it?” he asked angrily.

“Forgive me, sir,” replied the dwarf, “but I’m not accustomed to drinking wine.”

“Well, I order you to. I won’t drink one drop of this wine until you’ve had some.”

“You needn’t worry.” Filippo smiled. He bowed, took the cup from Baldassare’s hands, drank a mouthful, and returned the cup to him. Baldassare looked at him, and then he drank the rest of the wine with one gulp.

It was hot. The lagoon sparkled with a blinding glimmer. Once again the lovers sought out the shadow of the curtains, while the dwarf sat down sideways at the bottom of the gondola, moved his hand over his wide forehead, and winced as if he were in pain.

He knew that in one hour he would no longer be alive. The drink had been poison. A strange sensation overwhelmed his soul, which was now very close to the gate of death. He looked back at the city and remembered the thoughts that had just absorbed his attention. Silently he stared over the glistening surface of the water and pondered his life. It had been monotonous and meager — a wise man in the service of fools, a vapid comedy. As he sensed that his heartbeat was becoming irregular and his forehead was covered with sweat, he began to laugh bitterly.

Nobody paid attention. The gondolier stood there half asleep, and behind the curtains the beautiful Margherita was horrified and worried, for Baldassare had suddenly become sick and then cold. Soon he died in her arms, and she rushed out from the cabin with a loud cry of pain. Her dwarf was lying dead on the floor of the gondola, as if he had fallen asleep in his splendid silk clothes.

Such was Filippo’s revenge for the death of his little dog. The return of the doomed gondola with the two dead men shocked all of Venice.

Signorina Margherita went insane but still lived many years more. Sometimes she sat by the railing of her balcony and called out to each gondola or boat that passed, “Save him! Save the dog! Save little Fino!” Everyone knew her, however, and paid her no attention.