Faldum

(1916)

Faldum

Faldum

The road leading to the city of Faldum ran right through some hills, and here and there along the way it was lined with woods, large green pastures, and wheat fields. The closer it came to the city, the more it passed barns, dairy farms, gardens, and country houses. The sea was too far away to be seen, and the world seemed to consist of nothing but small hills, pretty valleys, meadows, woods, farmlands, and orchards. It was a country that had plenty of fruit and wood, milk and meat, apples and nuts. The villages were very attractive and clean, and the people were on the whole upright and diligent and did not like to undertake dangerous or disturbing projects. They felt satisfied if they could keep up with their neighbors and if their neighbors kept up with them. That was how life was in Faldum, and most countries in the world are the same, as long as unusual things do not happen.

On this morning, the pretty road that led to Faldum (the surrounding country had the same name) had become extremely lively since the cock first crowed. It bustled with people and wagons and carriages just as it did once each year, for the city held its great fair that day. Indeed, every single farmer and farmer’s wife, every single master, apprentice, and farmhand, every single maiden and lad within twenty miles of the city had been thinking of the great fair for weeks and dreaming of visiting it. Of course, not everyone could go. Someone had to stay behind and look after the animals and small children, the sick and the old, and once lots were drawn, the person who lost had to remain at home and take care of house and farm. For those people, it seemed that almost a year of their lives had been futile, and everything was spoiled for them, including the beautiful sun, which stood warm and jubilant in the blue sky of late summer starting early that morning.

The women and young girls carried small baskets on their arms as they walked, and the young men with clean-shaven cheeks had pink carnations and asters in their lapels. Everyone was clad in neat Sunday clothes, and the schoolgirls had carefully braided their hair, which was still wet and sparkling in the sunshine. Those people riding in carriages wore flowers or had little red ribbons tied to the handle of the whips, and whoever could afford it had decorated the harness of his horses with brightly polished brass disks that hung along the wide decorative leather down to their legs. Rack wagons came by, whose green roofs of beech branches were bent in arches over the seats, and beneath the roofs people sat crowded together with children or baskets on their laps, most of them singing loudly in a chorus. Every now and then a wagon appeared among the others that was especially colorful, decorated with flags and paper flowers, red and blue and white, mixed in with the green leaves of the beech branches. Village music resounded bombastically from this wagon, and through the branches one could see the gold horns and trumpets gleaming softly and exquisitely in the half shadows. Little children who had been obliged to walk since sunrise began to weep from exhaustion and were comforted by their perspiring mothers. Many of them were given lifts by kind and generous drivers. An old woman was pushing twins in a carriage, both asleep, and between the sleeping children’s heads lay two dolls, beautifully dressed and combed with cheeks just as round and red as those of the babies.

Those people who lived along the way but were not going to the fair this day had an entertaining morning because there was so much to see. Yet only a very few did stay at home. A ten-year-old boy sitting on the garden stairs wept because he had to remain with his grandmother. But after he sat and cried for what he thought was a sufficient amount of time, he leaped onto the road and joined some village boys as they came marching by.

Not far from there lived an old bachelor who wanted nothing to do with the fair because he did not like to spend his money. He intended to spend the day trimming the high hawthorn hedge around his garden while everyone was away celebrating, for it needed cutting. As soon as the morning dew began to evaporate, he went cheerfully about his work with his big hedge shears. But after working just about an hour, he stopped and retreated angrily into his house, for each and every boy who had come by, either on foot or on horseback, had gazed in astonishment at the man cutting the hedge and made some sort of joke about his untimely zeal, while the girls had joined in with laughter. When the old man threatened them with his long shears, they had all swung their hats, waved, and mocked him. Now he sat inside behind locked shutters; yet he peered through the cracks with envy, and when his anger gradually subsided and he saw the last few people dashing to the fair as though their lives depended on it, he put on his boots, stuck a taler into his pouch, took a cane, and got set to go. Suddenly it occurred to him that a taler was indeed a lot of money. So he pulled it out of the leather pouch, replaced it with half a taler, and tied the pouch with a string. Then he put it into his pocket, locked the house and garden gate, and ran so fast that he passed many pedestrians and even two wagons on his way to the city.

Once he was gone and his house and garden stood empty, the dust settled gently on the road. The sounds of trotting horses and brass bands floated and faded away. The sparrows began to come out of the fields of stubble. Bathed in the white dust, they inspected what was left over from the tumult. The road was empty and dead and hot. From the remote distance shouts of joy and sounds of music still drifted from time to time, faint and lost.

Just then a man emerged from the forest. The broad brim of his hat sloped over his eyes, and he meandered casually all by himself along the deserted country road. He was a large man and had the firm, calm stride of a wanderer who has traveled a great deal on foot. His clothes were plain and gray, and his eyes peered out from the shadow of his hat, carefully and serenely leaving the impression of a man who desires nothing from the world but observes everything with great attention. Indeed, nothing escaped his view. He saw the countless tangled wagon tracks running ahead of him. He saw the hoof marks of a horse that limped on its left hind foot. He saw the tiny glimmering roofs of Faldum rise on the hill in the distance. He saw a little woman, anxious and desperate, wandering about a garden as if lost and calling for someone who did not answer. He saw a small piece of metal flash on the edge of the road, and he bent over and picked up a bright round brass disk that a horse had lost from its collar. He put it into his pocket. And then he saw an old hawthorn hedge that had just been partially trimmed. The first part of the work was precise and clean and seemed to have been done with pleasure. Yet as he went along the hedge, he saw that less and less care had been taken, so that there were deep cuts, and neglected branches stuck out with sharp bristles and thorns.

Farther on the stranger found a child’s doll lying on the road. A wagon wheel must have run over its head. He saw a piece of rye bread still gleaming with melted butter. Finally, he found a sturdy leather pouch with a half taler inside it. He leaned the doll against a curbstone at the edge of the road, crumbled the bread and fed the pieces to the sparrows, and stuck the pouch with the half taler into his pocket.

It was incredibly silent on the abandoned road. The turf on both sides was thick with dust and parched by the sun. Chickens ran around a nearby farmyard, and nobody could be seen far and wide as the chickens clucked and stuttered dreamily in the warm sun. But then he saw an old woman leaning over a bluish cabbage patch and pulling weeds from the dry ground. The wanderer called out and asked her how far it was to the city. She was deaf, however, and when he called again louder, she only looked at him helplessly and shook her gray head.

As the stranger walked on, he heard the sounds of music rise and fall from the city. They became more frequent and longer the closer he came to the city, until they flowed continually like a distant waterfall, music and the murmur of voices, as if all the people had gathered together and were enjoying themselves there. Now a stream flowed next to the road, wide and quiet. There were ducks on it, and brown-green water weeds beneath the blue surface. When the road began to climb, the stream curved to the side, and a stone bridge traversed it. A thin man, who looked like a tailor, was asleep atop the low wall of the bridge, with his head slumped over. His hat had fallen down into the dust, and sitting next to him, a small cute dog kept guard over him. The stranger wanted to wake the tailor because he could easily fall over the wall of the bridge while sleeping. However, once he looked over the wall, the stranger realized that it was not very high, and the water was shallow. So he let the tailor continue sleeping.

After walking up a steep footpath, the stranger came at last to the city gate of Faldum. It was wide open, and not a person was to be seen. The man strode through the gate, and suddenly his footsteps echoed loudly on a paved street, where a row of empty, unharnessed wagons and carriages were stationed alongside the houses. Some signs of life and noise sounded from other streets, but not a single soul could be found here. The little street was filled with shadows, and only the upper windows of the houses reflected the golden day. The wanderer rested here for a short time, sitting on the shaft of a rack wagon. Before he set off again, he placed the brass disk of the harness that he had found alongside the road on the driver’s seat.

He had walked no farther than a block before he was engulfed by the noise and tumult of the fair. There were a hundred booths, and dealers were shouting loudly and trying to sell their goods. Children blew silver-tinseled horns. Butchers fished strings of wet sausages from large boiling kettles. A medicine man posing as a doctor stood high on a platform and peered eagerly through his thick horn-rimmed glasses. He had set up a chart that pictured all sorts of human diseases and maladies. A man with long black hair passed by his booth leading a camel by a rope. With its long neck, the camel looked arrogantly down at the crowd of people, moved its split lips back and forth, and made signs of chewing.

The man from the woods scanned everything with great interest. He let himself be pushed and shoved by the crowd. He glanced into the booth of a man who sold colored prints. At another booth he read the sayings and mottos on sugar-coated gingerbread cookies. He did not stay at any one place very long, however, and seemed to be looking for something that he had not yet found. So he moved forward slowly until he came to the large central square where a bird dealer was setting up a cage on the corner. There he listened for a while to the voices that came from the many small cages, and he answered them by whistling softly to the linnet, the quail, the canary, and the warbler.

Suddenly he was attracted by something nearby, something bright and dazzling, as if all the sunshine were concentrated on this one spot, and when he headed in that direction, he came upon a mirror hanging in a booth. Next to it were other mirrors, hundreds of them, big and small, square, round, and oval, mirrors to be hung on walls and to stand up. There were also hand mirrors and small, thin pocket mirrors that you could take anywhere, so that you would not forget your own face. The dealer stood there, caught the sun in a bright mirror, then let the sparkling reflection dance over his booth. Meanwhile, he shouted incessantly, “Mirrors, ladies and gentlemen, buy your mirrors here! The best mirrors! The cheapest mirrors in Faldum! Mirrors, ladies, splendid mirrors! Just take a look. Everything’s genuine. The very best crystal!”

The stranger stopped at the booth of mirrors and appeared to find what he was looking for. Among the people examining the mirrors were three young girls from the countryside. He moved to a spot close by and watched them. They were lively and robust peasant girls, neither beautiful nor ugly, wearing thick-soled shoes and white stockings. Their blond braids had been somewhat bleached by the sun, and they had bright young eyes. Each girl had taken an inexpensive mirror in her hand, and as all three hesitated and deliberated whether they should buy, while also enjoying the sweet torment of choosing, each looked forlornly and dreamily into the translucent depths of the mirror and regarded her reflection, her mouth and eyes, the small jewel of her necklace, the freckles around her nose, the smooth part in her hair, and the rosy ear. Then they became silent and serious. The stranger, who stood right behind the girls, saw their large, almost jubilant eyes and reflections gazing at him from the mirrors.

“Oh,” he heard the first girl say, “I wish I had long hair, shiny red hair, that hung down to my knees!”

Upon hearing her friends wish, the second girl sighed softly and looked deep into her mirror. Then she, too, divulged her heart’s dream with a blush and said shyly, “If I could wish, I’d like to have the most beautiful hands, totally white and delicate, with long slender fingers and rosy fingernails.” As she said this, she looked at her hand holding the oval mirror. The hand was not ugly, but the fingers were a bit short and thick and had become coarse and hardened from work.

The third girl, the smallest and most vivacious of the three, laughed at all this and cried merrily, “That’s not a bad wish! But you know, hands aren’t all that important. What I’d prefer most of all would be to become the best and most nimble dancer in the whole country of Faldum from this moment on.”

All of a sudden the girl jumped in fright and turned around. A strange face with black glaring eyes had been looking out at her in the mirror from behind her own face. It was the face of the stranger, who had stepped behind her, and until then the three girls had not noticed him. Now they stared into his face with amazement, while he nodded to them and said, “You’ve made three beautiful wishes, my girls. Do you really mean what you’ve said?”

The small girl put down the mirror and hid her hands behind her back. She wanted to pay the man back for frightening her and was thinking of a sharp word or two to say to him. But when she looked into his face, she saw so much power in his eyes that she became timid.

“Does it matter to you what I wish?” she said simply, and turned red.

But the other girl, who had wished for the elegant hands, felt that she could trust him. There was something fatherly and distinguished about him.

“Yes,” she said. “We are serious about what we said. Can one wish for anything more beautiful?”

The mirror dealer had joined them, and now other people, too, were listening. The stranger had turned up the brim of his hat so that everyone could see his smooth, high forehead and imperious eyes. Now he nodded to the three girls in a friendly way, smiled, and announced, “Look, you already have what you wished for!”

The girls gazed at one another and then looked into their mirrors. Suddenly all three of them turned pale out of astonishment and joy. The first girl’s hair had turned into thick golden-red locks that hung down to her knees. The second was holding her mirror in the slenderest and whitest hands, just like those of a princess, and the third was suddenly wearing red leather dancing shoes, standing with ankles as slim as those of a deer. None of the girls could grasp what had happened, but the girl with the elegant hands burst into tears of joy. She leaned on her friend’s shoulder and wept blissfully into her long golden-red hair.

Now the story of the miracle spread by word of mouth and through loud cries all around the booth. A young journeyman who had watched everything stood and stared at the stranger with wide-open eyes, as though he were paralyzed.

“Would you like to wish for something?” the stranger asked him all at once.

The journeyman was frightened and completely confused. He looked around helplessly to spot something to wish for. Then he saw an enormous string of thick red sausages hanging in front of the pork butcher’s stand, and he stammered as he pointed to it.

“I’d like to have a string of sausages like that.”

No sooner did he say this than a wreath of sausages hung around his neck, and everyone present began to laugh and shout. People tried to move closer, and everyone wanted to make a wish. And they were all allowed to do so. The very next man was bolder and wished for new Sunday clothes from top to bottom. All at once he was wearing a fine, brand-new suit more elegant than that of the mayor. Then a country woman came up and, after summoning her courage, demanded ten talers on the spot. Immediately the talers were jingling in her pocket.

Now the people saw that real miracles were actually happening, and the news spread like wildfire throughout the marketplace and the city. People gathered rapidly in large crowds all around the booth of the mirror dealer. Many laughed and joked; others did not believe a thing and voiced their doubts. But many had already been infected by the wish-fever and came running with glowing eyes and hot faces distorted by greed and need, for they all feared that the source of the wishes might dry up before they could dip into it. Little boys wished for cookies, crossbows, bags of nuts, books, and bowling games. Little girls went away happy with new clothes, ribbons, gloves, and umbrellas. A little ten-year-old boy, who had run away from his grandmother and was excited by all the glories and splendor of the fair, wished in a clear voice for a live pony, but it had to be black. All at once a black colt neighed behind him and rubbed its head warmly on his shoulder.

An old bachelor with a walking stick in his hand forced his way through the crowd, which was totally intoxicated by the magic, and stepped forward trembling. He could barely speak a word because he was so excited.

“I wish,” he said, stuttering, “I wi-wi-wish two hundred times—”

The stranger looked at him closely, then pulled a leather pouch out of his pocket and held it before the eyes of the excited little man.

“Wait a second!” said the stranger. “Didn’t you lose this money pouch? There’s half a taler inside.”

“Yes, I did!” exclaimed the bachelor. “It’s mine.”

“Do you wish to have it back?”

“Yes, give it to me.”

So he recovered his pouch, but at the same time he wasted his wish, and when he realized this, full of anger he lifted his cane against the stranger and tried to hit him, but he missed and smashed a mirror. The pieces of glass were still clinking as the dealer came over and demanded money, and the bachelor had to pay.

Now a stout house-owner approached and made a splendid wish. To be precise, he wished for a new roof for his house, and within seconds it glistened from his street with brand-new tiles and a chimney as white as chalk. Then everyone was stirred up once more and began to wish for bigger and better things. Soon one man was not embarrassed to wish for a new four-story house on the marketplace, and a quarter of an hour later he was leaning over his own windowsill and observing the fair from there.

Actually there was no longer a fair since everyone and everything in the city was flowing like a river from a source — the spot by the booth of mirrors, where the stranger stood and allowed each person to make a wish. Cries of astonishment, envy, or laughter followed each wish, and when a hungry little boy wished for nothing more than a hatful of plums, his hat was refilled with taler coins by one of the people whose wish had been less modest. The fat wife of a grocer received great applause and cheers when she wished away a heavy goiter. But then the people were given an example of what anger and resentment can do. Her own husband, who was unhappily married to her and had just had a bad argument with her, used his wish, which could have made him rich, to restore the goiter to the same place where it had been before. Nevertheless, the better precedent had already been set, and a group of feeble and sick people were brought to the booth. The crowd became delirious again when the lame people began to dance and the blind greeted the light with blessed new eyes.

In the meantime the young people had already run all over the city announcing the miraculous events. They told everyone, including a loyal old cook who was standing at the hearth and roasting a goose for the family in the house where she worked. When she heard the news about the wishes through the window, she, too, could not resist running to the marketplace to wish herself rich and happy for the rest of her life. Yet the more she pushed her way through the crowd, the more perceptibly her conscience began to bother her, and when it was her turn to wish, she gave up everything and desired only that the goose not burn before she was back home tending it.

The tumult did not end. Nursemaids rushed out of houses dragging children by their arms. Excited invalids jumped out of their beds and ran out onto the streets in their nightgowns. A little woman, very confused and desperate, arrived from the countryside, and when she heard about the wishes, she sobbed and begged that she might find her lost grandson safe and sound. Within seconds, the boy came riding up on a small black pony and fell laughing into her arms.

In the end, the entire city gathered and became ecstatic. Couples in love whose wishes had been fulfilled wandered arm in arm. Poor families drove around in carriages, still wearing their old patched clothes from that morning. Many people who regretted making a foolish wish either departed sadly or were drinking themselves into forgetfulness at the old fountain in the marketplace that a jokester had filled with the very best wine through his wish.

Eventually there were only two people in the entire city of Faldum who did not know anything about the miracle and had not made wishes for themselves. They were two young men, and they were up high in the attic of an old house at the edge of the city, behind closed windows. One of them stood in the middle of the room, held a violin under his chin, and played with all his soul and passion. The other sat in a corner, held his head between his hands, and was completely absorbed in listening. The sun shone obliquely through the small windowpanes and cast a bright hue, illuminating a bouquet of flowers standing on the table, and its rays played on the torn wallpaper. The room was completely filled with warm light and the glowing tones of the violin, like a small secret treasure chamber glistening with the luster of precious stones. The violinist had closed his eyes and now swayed back and forth as he played. The listener stared quietly at the floor and was lost in the music as if there were no life in him.

Then loud footsteps pounded outside on the street. The door of the house burst open, and the steps came rumbling up the stairs all the way to the attic room. It was the landlord, and he ripped the door open and barged into the room with yells and laughter. The violin music broke off at once, and the silent listener leaped into the air, distraught. The violinist was angry at being interrupted, and he glared reproachfully at the landlord’s laughing face. But the man paid no attention to this. Instead, he waved his arms like a drunkard and screamed, “You fools! You sit here and play the violin, and outside the entire world is being changed. Wake up and run so that you won’t be too late! There’s a man at the marketplace granting wishes to everyone and making them come true. If you hurry, you won’t have to live in this tiny attic anymore and owe me the measly rent. Get up and go before it’s too late! Even I’ve become a rich man today!”

The violinist listened with astonishment, and since the man would not leave him in peace, he set the violin down and put his hat on his head. His friend followed without saying a word. No sooner did they leave the house than they saw that half the city had already changed in the most remarkable way, and they walked past the houses somewhat uneasily, as if in a dream. Yesterday these houses had been gray and crooked, humble dwellings. Now, however, they stood tall and elegant like palaces. People whom they had known as beggars were driving around in four-horse carriages, or they were now proud and affluent and looking out of the windows of their beautiful houses. A haggard-looking man who resembled a tailor, followed by a tiny dog, plodded along, tired and sweaty, dragging a large heavy sack, and gold coins trickled through a small hole onto the pavement.

Almost automatically, the two young men arrived at the marketplace and found themselves before the booth with mirrors. The stranger standing there said to them, “You’re not in much of a hurry to make your wishes. I was just about to leave. Well, tell me what you want, and feel free to make any wish you desire.”

The violinist shook his head and said, “Oh, if only you had left me in peace! I don’t need anything.”

“Are you sure? Think about it!” cried the stranger, “You may wish for anything that comes to your mind. Anything.”

Then the violinist closed his eyes and contemplated for a while. Finally he spoke in a soft voice and said, “I wish I could have a violin and play it in such a wonderful way that nothing in the whole world would be able to disturb me with its noise anymore.”

Within seconds he held a beautiful violin and bow in his hands. He tucked the violin beneath his chin and began to play. The music sounded sweet and rhapsodic like the song of paradise. Whoever heard it stopped still and listened with somber eyes. As the violinist played more and more intensely and magnificently, however, he was lifted up by invisible forces and disappeared into thin air. His music continued to resound from a distance with a soft radiance like the red glow of the sunset.

“And you? What do you wish?” the man asked the other young man.

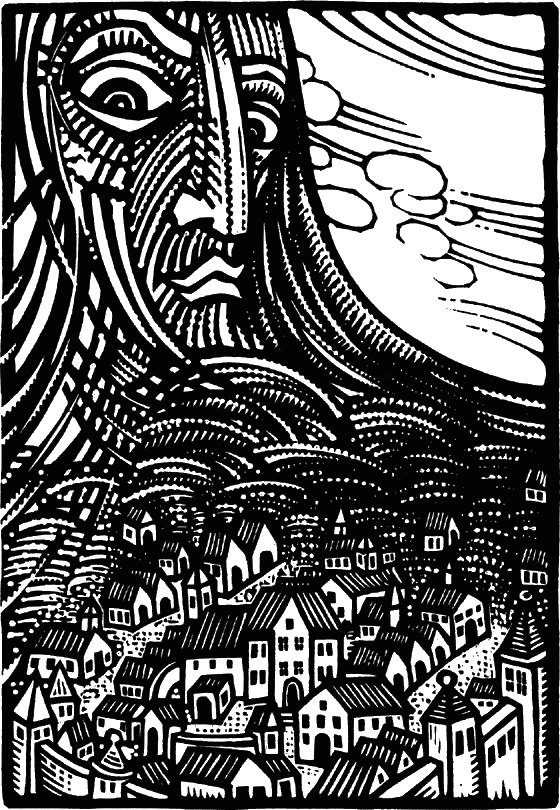

“You’ve taken the violinist away from me!” complained the young man. “Now the only thing I want from life is to be able to listen and observe, and I want only to think about things immortal. So I wish I were a mountain as large as the country of Faldum, so tall that my peak would tower above the clouds.”

All at once there was a rumbling beneath the earth, and everything began to sway. The glass clattered and broke. The mirrors fell one by one in splinters onto the pavement. The marketplace rose up as a sheet rises when a cat that has fallen asleep underneath awakes and arches its back up high. The people were overwhelmed by terror. Thousands screamed and began fleeing the city into the fields. Those who remained at the marketplace watched a mighty mountain climb behind the city into the evening clouds. Beneath it they saw the quiet stream transformed into a white and wild mountain torrent that rushed from the top of the mountain with many falls and rapids down into the valley below.

Only a moment had passed, and yet the entire countryside of Faldum had turned into a gigantic mountain. At its foot was the city, and far away in the distance the ocean could be seen. Nobody had even been harmed in the process.

An old man who had been standing beside the booth of mirrors and had witnessed everything said to his neighbor, “The world’s gone mad. I’m happy that I don’t have much longer to live. I’m only sorry about the violinist. I’d like to hear him just one more time.”

“Yes, indeed,” said the other. “But tell me, where’s the stranger gone to?”

They looked around, but he had vanished. When they gazed up at the new mountain, however, they saw the stranger up high, walking away with his cape fluttering in the wind. He stood for a moment, a gigantic figure against the evening sky, then disappeared around the corner of a cliff.

The Mountain

The Mountain

Everything passes away in time, and everything new grows old. The annual fair had long ago become history, and many people who wished themselves rich on that occasion had become poor again. The girl with the long golden-red hair had married and had children, who also went to the fair in the city in the late summer of each year. The girl with the nimble dancing feet had become the wife of a guild master in the city, and she could still dance splendidly, much better than many young people. Though her husband had wished for a lot of money, it seemed as though the merry couple would run through all of it before the end of their lives. However, the third girl with the beautiful hands still thought about the stranger at the mirror booth more than anyone else. Though this girl had never married and had not become rich, she still had her delicate hands, and because of her hands she had stopped doing farm work and instead looked after the children in her village wherever she was needed and told them fairy tales and stories. Indeed, it was from her that all the children learned about the miraculous fair, and how the poor had become rich and how the country of Faldum had become a mountain. Whenever she told this story, she would look at her slender princess hands, smile, and become so moved and full of love that one was apt to believe that nobody had received a better fortune at the booth of mirrors than she had, even though she was poor and without a husband and had to tell beautiful stories to children who were not her own.

Everyone who had been young at that time was now old, and those who had been old were now dead. Only the mountain stood unchanged and ageless, and when the snow on his peak glistened, he seemed to smile and be happy that he was no longer a human being and no longer had to calculate according to standards of human time. The cliffs of the mountain beamed high above the city and the countryside. His tremendous shadow wandered every day over the land. His streams and rivers announced in advance the change of the seasons. The mountain had become the protector and father of all. He generated forests and meadows with waving grass and flowers. He produced springs, snow, ice, and stones. Colorful grass grew on the stones, and forget-me-nots alongside the streams. Deep down in the mountain were caves where water dripped like silver threads year after year from stone to stone in eternal rhythm, and in his chasms were secret chambers where crystals grew with a thousand-year patience. Nobody had ever reached the peak of the mountain. But many people claimed to know that there was a small round lake way up on the top, and that nothing but the sun, moon, clouds, and stars had ever been reflected in it. Neither human nor animal had ever looked into this basin of water that the mountain held up toward the heavens, for not even the eagles could fly that high.

The people of Faldum lived on cheerfully in the city and in the numerous valleys. They baptized their children. They were active in trading and in the crafts. They carried one another to their graves. Their knowledge of and dreams about the mountain were passed on from grandparents to grandchildren and lived on. Shepherds and chamois hunters, naturalists and botanists, cowherds and travelers increased the treasured lore of the mountain, and ballad singers and storytellers passed it on. They knew all about the endless dark caves, about waterfalls without light in hidden chasms, about glaciers that split the land in two. They became familiar with the paths of the avalanches, and the unpredictable shifts in the weather, and what the country might expect in the way of heat and frost, water and growth, weather and wind — all this came from the mountain.

Nobody knew anything more about the earlier times. Of course, there was the beautiful legend about the miraculous annual fair, at which every single soul in Faldum had been allowed to wish for whatever he or she wanted. But nobody wanted to believe anymore that the mountain himself had arisen on that day. They were certain that the mountain had stood in his place from the very beginning of time and would continue to stand there for all eternity. The mountain was home. The mountain was Faldum. More than anything the people loved to hear the stories about the three girls and about the violinist. Sometimes a young boy would abandon himself while playing the violin behind a closed door and dream of disappearing in beautiful music like the violinist who had drifted into the sky.

The mountain lived on silently in his greatness. Every day he watched the sun, far away and red, climb from the ocean and circle around his peak from east to west, and every night he watched the stars take the same silent path. Each winter the mountain would be wrapped in a coat of snow and ice, and each year the avalanches would rumble at a given time down his sides, and at the edge of the remains of the snow, the bright-eyed summer flowers, blue and yellow, laughed in the sun, and the streams swelled and bounced, and the lakes sparkled with more blue and more warmth in the sunlight. Lost water thundered faintly in invisible chasms, and the small round lake high upon the peak lay covered with heavy ice and waited the entire year to open its bright eyes during the brief period of high summer when for a few days it could reflect the sun and for a few nights the stars. The water in the dark caves caused the stones to chime in eternal dripping, and in secret gorges the thousand-year crystals grew steadfastly toward perfection.

At the foot of the mountain, a little higher than the city, there was a valley through which a wide brook with a smooth surface flowed between alders and meadows. The young people who were in love went there and learned about the wonders of the seasons from the mountain and trees. In another valley the men held their training exercises with horses and weapons, and each year during the eve of solstice, an enormous fire burned on one of the high steep knolls.

Time flew by, and the mountain protected the valley of love and the training ground. He provided space to the cowherds, woodcutters, hunters, and craftsmen. He gave stones for building and iron for smelting. He watched calmly and let the summer fire blaze on the knoll and watched the fire return a hundred times and another hundred times. He saw the city below reach out with small stumpy arms and grow beyond its old walls. He saw hunters discard their crossbows and turn to firearms to shoot. The centuries passed like the seasons of the year and the years like hours.

He did not care that one time over the years the solstitial fire had stopped burning on the rocky plateau and from then on remained forgotten. He was not troubled when, after many years passed, the training grounds became deserted, and plantain and thistle ran all over the fields. And as the centuries marched on, he did not prevent a landslide from altering his shape and causing half the city of Faldum to lie in ruins under the rocks that rolled down upon it. Indeed, he rarely glanced down and thus did not even notice that the city remained in ruins and was not rebuilt.

He did not care about any of this. But something else began to be of concern. The times raced by, and behold — the mountain grew old. When he saw the sun rise and wander and depart, he was not the same way he had once been, and when he saw the stars reflected in pale glaciers, he no longer felt himself their equal. The sun and stars were now no longer particularly important to him. What was important now was what was happening to himself and within himself, for he felt a strange hand working deep beneath his rocks and caves. He felt the hard primitive stone becoming brittle and crumbling away into layers of slate, the brooks and waterfalls causing corrosion inside. The glaciers had disappeared and lakes had grown. Forests were transformed into fields of stone, and meadows into black moors. The hollow patches of his moraines and gravel spread endlessly into the country with forked tongues, and the landscape below had become strangely different, strangely rocky, strangely scorched and quiet. The mountain withdrew more and more into himself. He felt certain that he was no longer the equal of the sun and stars. His equals were the wind and snow, the water and ice. His equals were the things that seemed to shine eternally and yet also disappeared slowly, the things that perished slowly.

He began to guide his streams down the valley more fervently, rolled his avalanches more carefully, and offered his meadows of flowers to the sun more tenderly. And it happened that in his old age he also began remembering about human beings again. Not that he now regarded people as his equal, but he began to look about for them. He began to feel abandoned. He began to think about the past. But the city was no longer there, and there was no song in the valley of love, and no more huts on the meadows. There were no more people there. Even they were gone. It had become silent. Everything had turned languid. A shadow hung in the air.

The mountain quivered when he felt all of that which had perished. And as he quivered, his peak sank to a side and collapsed. Pieces of rock rolled down into the valley of love, long since filled with stones, and down into the sea.

Yes, the times had changed. But what was it that caused him to remember and think about people so constantly now? Hadn’t it once been wonderful when they burned the solstitial fire on the knoll and when young couples walked in the valley of love? Oh, and how sweet and warm their songs had often sounded!

The gray mountain became entirely steeped in memory. He barely felt the centuries flowing by. Nor did he pay much attention to how his caves were softly rumbling and collapsing here and there, or to how he shifted himself. When he thought about the people, he felt the pain of a faint echo from past ages of the world. It was as if something had moved and love had not been understood, a dark, floating dream, as if he had also once been human or similar to a human, had sung and had listened to singing, as if the thought of mortality had once ignited his heart when he was very young.

Epochs rushed by. The dying mountain clung to his dreams as he sank and was surrounded by a crude wasteland of stone. How had everything been at one time? Wasn’t there still a sound, a delicate silver thread that linked him to a bygone world? He burrowed with great effort into the night of moldy memories, groped relentlessly for the torn threads, bent constantly far over the abyss of the past.

Hadn’t he had a community, a love that glowed for him at one time? Hadn’t a mother sung to him at one time at the beginning of the world?

He thought and thought, and his eyes, the blue lakes, became murky and heavy and turned into moors and swamps, while stone boulders rippled over the grassy strips of land and small patches of flowers. He continued to think, and he heard chimes from an invisible distance, felt notes of music floating, a song, a human song, and he began trembling in the painful pleasure of recognition. He heard the music, and he saw a man, a youth, completely wrapped in music, swaying through the air in the sunny sky, and a hundred buried memories were stirred and began to quiver and roll. He saw the face of a human with dark eyes, and the eyes asked him with a twinkle,

“Don’t you want to make a wish?”

And he made a wish, a silent wish, and as he did so, he was released from the torment of having to think about all those remote and forgotten things, and everything that had been hurting him ceased. The mountain and the country collapsed together, and where Faldum had once stood, the endless sea now surged and roared far and wide, and the sun and stars took turns appearing high above it all.