Книга: Английский для смелых. Истории о духах и привидениях / Great Ghost Stories

Назад: The Moonlit Road (Дорога, залитая лунным светом[10]) Ambrose Bierce (Амброз Бирс)

Дальше: II. Statement of Caspar Grattan (Cвидетельство Каспара Грэттена)

I. Statement of Joel Hetman, JR

(Cвидетельство Джоэла Хетмена-младшего)

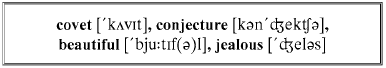

I am the most unfortunate of men (я самый несчастный из людей). Rich (богатый), respected (уважаемый), fairly well educated (довольно хорошо образованный; fairly – красиво, мило; довольно) and of sound health (крепкого здоровья) – with many other advantages usually valued by those having them and coveted by those who have them not (со многими другими преимуществами, обычно ценимыми теми, у кого они есть, и которыми стремятся обладать те, у кого их нет; to covet – жаждать, домогаться, сильно желать) – I sometimes think that I should be less unhappy if they had been denied me (я иногда думаю, что я был бы менее несчастен, если бы ничего этого у меня не было: «если бы в них /этих преимуществах/ мне было отказано»), for then the contrast between my outer and my inner life would not be continually demanding a painful attention (ибо тогда контраст между моей внешней и внутренней жизнью не требовал бы постоянного пристального внимания; painful – мучительный, тягостный, требующий больших усилий; pain – боль). In the stress of privation and the need of effort (будучи поставлен перед необходимостью бороться с лишениями и лишенный возможности предаваться праздности: «под стрессом лишений и необходимости прилагать усилия»; effort – усилие, напряжение) I might sometimes forget the somber secret (я, возможно, временами забывал бы мрачную тайну) ever baffling the conjecture that it compels (постоянно ставящую в тупик попытки ее разгадать, вызываемые самим ее существованием; to baffle – ставить в тупик; сбивать с толку; conjecture – догадка, предположение; to compel – заставлять, вынуждать).

I am the only child of Joel and Julia Hetman (я единственный ребенок Джоэла и Джулии Хетмен). The one was a well-to-do country gentleman (первый был зажиточным сельским джентльменом), the other a beautiful and accomplished woman (другая – красивой и превосходно воспитанной женщиной; accomplished – получивший хорошее образование; воспитанный; культурный) to whom he was passionately attached with what I now know to have been a jealous and exacting devotion (к которой он был пылко привязан узами того, что, как я сейчас знаю, было ревнивой и требовательной привязанностью; to attach – прикреплять; привязывать, располагать к себе; devotion – преданность; сильная привязанность). The family home was a few miles from Nashville, Tennessee (наш дом: «семейный дом» находился в нескольких милях от Нэшвилля, штат Теннесси), a large, irregularly built dwelling of no particular order of architecture (большое, беспорядочно построенное здание, не относящееся ни к какому определенному архитектурному стилю; dwelling – жилище, жилое помещение; particular – редкий, особенный, специфический; индивидуальный, отдельный; order – порядок, система, соблюдение каких-либо правил), a little way off the road, in a park of trees and shrubbery (немного в стороне от дороги, в парке из деревьев и кустарников).

I am the most unfortunate of men. Rich, respected, fairly well educated and of sound health – with many other advantages usually valued by those having them and coveted by those who have them not – I sometimes think that I should be less unhappy if they had been denied me, for then the contrast between my outer and my inner life would not be continually demanding a painful attention. In the stress of privation and the need of effort I might sometimes forget the somber secret ever baffling the conjecture that it compels.

I am the only child of Joel and Julia Hetman. The one was a well-to-do country gentleman, the other a beautiful and accomplished woman to whom he was passionately attached with what I now know to have been a jealous and exacting devotion. The family home was a few miles from Nashville, Tennessee, a large, irregularly built dwelling of no particular order of architecture, a little way off the road, in a park of trees and shrubbery.

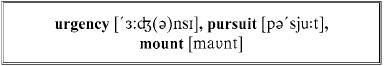

At the time of which I write I was nineteen years old, a student at Yale (в описываемое мной время: «в то время, о котором я пишу» мне было девятнадцать лет, /я был/ студентом Йельского университета). One day I received a telegram from my father of such urgency (однажды я получил такую императивную телеграмму от отца; urgency – безотлагательность, срочность; настойчивость) that in compliance with its unexplained demand I left at once for home (что, подчиняясь ее ничем не объясненному требованию приехать: «в соответствии с ее необъясненным требованием», я немедленно отправился домой; to leave – оставлять, покидать; уезжать). At the railway station in Nashville a distant relative awaited me to apprise me of the reason for my recall (на железнодорожной станции в Нэшвилле мой дальний родственник ожидал меня, с тем чтобы сообщить мне причину моего вызова; to apprise – извещать, информировать; recall – призыв вернуться): my mother had been barbarously murdered (моя мать была варварски убита) – why and by whom none could conjecture (почему и кем, никто /и/ предположить не мог), but the circumstances were these (но обстоятельства были следующие):

My father had gone to Nashville, intending to return the next afternoon (мой отец отправился в Нэшвилль, намереваясь вернуться на следующий день). Something prevented his accomplishing the business in hand (что-то помешало ему завершить намеченные дела; hand – рука /кисть/; in hand – в работе; в стадии рассмотрения), so he returned on the same night, arriving just before the dawn (поэтому он вернулся в ту же ночь, прибыв как раз перед рассветом). In his testimony before the coroner he explained that having no latchkey and not caring to disturb the sleeping servants (в своих показаниях коронеру он объяснил, что, поскольку у него не было ключа от входной двери и ему не хотелось будить спящих слуг; latch – задвижка, защелка, щеколда; key – ключ; latchkey – ключ от внешней двери или калитки; to care – беспокоиться, тревожиться; иметь желание; to disturb – волновать, тревожить; доставлять хлопоты, причинять беспокойство), he had, with no clearly defined intention, gone round to the rear of the house (он, без какого-либо конкретного: «ясно определенного» намерения, зашел с тыльной стороны дома: «обошел кругом к тылу дома»). As he turned an angle of the building, he heard a sound as of a door gently closed (когда он повернул за угол дома, он услышал звук, словно кто-то осторожно прикрывал дверь; gently – мягко, нежно; осторожно), and saw in the darkness, indistinctly, the figure of a man (и увидел в темноте, неотчетливо, мужской силуэт; figure – фигура /человека/; внешние очертания), which instantly disappeared among the trees of the lawn (который тут же исчез среди деревьев лужайки). A hasty pursuit and brief search of the grounds (когда торопливое преследование и поверхностный осмотр участка; brief – короткий, недолгий; search – поиски, розыск) in the belief that the trespasser was some one secretly visiting a servant proving fruitless (в предположении, что незнакомец был тайным поклонником кого-то из прислуги, не принесли результатов: «что нарушитель был кто-то, тайком посещавший прислугу, оказались бесплодными»; belief – мнение, убеждение; trespasser – лицо, вторгающееся в чужие владения; to prove – доказывать; оказываться), he entered at the unlocked door and mounted the stairs to my mother’s chamber (он вошел через незапертую дверь и поднялся в комнату моей матери; stairs – лестница). Its door was open (ее дверь была отворена), and stepping into black darkness he fell headlong over some heavy object on the floor (и, шагнув в непроглядную темноту, он споткнулся о что-то тяжелое, лежащее на полу, и упал ничком: «шагнув в черную темноту, он упал головой вперед на какой-то тяжелый предмет на полу»; headlong – головой вперед). I may spare myself the details (я могу избавить себя от подробностей; to spare – беречь, жалеть, сберегать, экономить; избавлять /от чего-либо/); it was my poor mother, dead of strangulation by human hands (это была моя бедная мать, удушенная: «мертвая от удушения» человеческими руками)!

At the time of which I write I was nineteen years old, a student at Yale. One day I received a telegram from my father of such urgency that in compliance with its unexplained demand I left at once for home. At the railway station in Nashville a distant relative awaited me to apprise me of the reason for my recall: my mother had been barbarously murdered – why and by whom none could conjecture, but the circumstances were these:

My father had gone to Nashville, intending to return the next afternoon. Something prevented his accomplishing the business in hand, so he returned on the same night, arriving just before the dawn. In his testimony before the coroner he explained that having no latchkey and not caring to disturb the sleeping servants, he had, with no clearly defined intention, gone round to the rear of the house. As he turned an angle of the building, he heard a sound as of a door gently closed, and saw in the darkness, indistinctly, the figure of a man, which instantly disappeared among the trees of the lawn. A hasty pursuit and brief search of the grounds in the belief that the trespasser was some one secretly visiting a servant proving fruitless, he entered at the unlocked door and mounted the stairs to my mother’s chamber. Its door was open, and stepping into black darkness he fell headlong over some heavy object on the floor. I may spare myself the details; it was my poor mother, dead of strangulation by human hands!

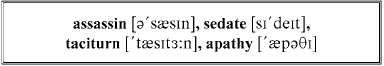

Nothing had been taken from the house (в доме ничего не пропало: «ничего не было взято из дома»), the servants had heard no sound (слуги ничего не слышали: «не слышали никакого звука»), and excepting those terrible finger-marks upon the dead woman’s throat (и за исключением тех ужасных отпечатков пальцев на горле = на шее мертвой женщины) – dear God! that I might forget them (Господи Боже мой: «дорогой Бог», если бы я мог их забыть)! – no trace of the assassin was ever found (никаких следов убийцы так и не было обнаружено).

I gave up my studies and remained with my father (я бросил свою учебу и остался со своим отцом; to give up – оставить, отказаться; бросить /что-либо/), who, naturally, was greatly changed (который, естественно, сильно переменился). Always of a sedate, taciturn disposition (/будучи/ всегда спокойного, молчаливого характера; sedate – спокойный, степенный, уравновешенный; disposition – нрав, характер), he now fell into so deep a dejection that nothing could hold his attention (он теперь впал в такое глубокое уныние, что ничто не могло удержать его внимания; dejection – сход, сошествие /вниз чего-либо/; упадок сил, подавленное настроение, уныние), yet anything – a footfall, the sudden closing of a door – aroused in him a fitful interest (и в то же время что угодно – шаги, внезапно закрытая дверь: «внезапное закрывание двери» – вызывало у него болезненный интерес; foot-fall = footfall – звук шагов; foot – ступня; to fall – падать, опускаться; to arouse – будить, пробуждать, возбуждать; fitful – судорожный; порывистый; fit – припадок); one might have called it an apprehension (кто-то бы даже назвал это манией преследования; apprehension – опасение; мрачное предчувствие). At any small surprise of the senses he would start visibly and sometimes turn pale (при любом малейшем внезапном чувственном восприятии: «при любой маленькой неожиданности чувств» он заметно вздрагивал и иногда бледнел; visibly – видимо, заметно, явно), then relapse into a melancholy apathy deeper than before (а затем вновь погружался в еще более глубокую меланхоличную апатию: «в меланхоличную апатию глубже, чем до того»; to relapse – снова впадать /в какое-либо состояние/). I suppose he was what is called a ‘nervous wreck’ (полагаю, он дошел тогда, что называется, до полного нервного истощения; wreck – развалина). As to me, I was younger then than now – there is much in that (что касается меня, тогда я был моложе, чем сейчас – а это многое значит: «в этом многое есть»). Youth is Gilead (молодость – это Галаад), in which is balm for every wound (где есть бальзам для каждой раны). Ah, that I might again dwell in that enchanted land (ах, если бы я вновь мог обитать в этой зачарованной стране)! Unacquainted with grief, I knew not how to appraise my bereavement (незнакомый с горем, я не знал, с чем соотнести мою утрату; to appraise – оценивать, расценивать, производить оценку; bereavement – тяжелая утрата; to bereave – лишать, отнимать, отбирать); I could not rightly estimate the strength of the stroke (я не мог полностью осознать: «правильно оценить» силу удара).

Nothing had been taken from the house, the servants had heard no sound, and excepting those terrible finger-marks upon the dead woman’s throat – dear God! that I might forget them! – no trace of the assassin was ever found.

I gave up my studies and remained with my father, who, naturally, was greatly changed. Always of a sedate, taciturn disposition, he now fell into so deep a dejection that nothing could hold his attention, yet anything – a footfall, the sudden closing of a door – aroused in him a fitful interest; one might have called it an apprehension. At any small surprise of the senses he would start visibly and sometimes turn pale, then relapse into a melancholy apathy deeper than before. I suppose he was what is called a ‘nervous wreck.’ As to me, I was younger then than now – there is much in that. Youth is Gilead, in which is balm for every wound. Ah, that I might again dwell in that enchanted land! Unacquainted with grief, I knew not how to appraise my bereavement; I could not rightly estimate the strength of the stroke.

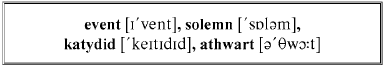

One night, a few months after the dreadful event, my father and I walked home from the city (однажды вечером, несколько месяцев спустя после того ужасного события, мы с моим отцом шли домой из города; night – ночь; вечер). The full moon was about three hours above the eastern horizon (полная луна уже как три часа поднялась на востоке: «над восточным горизонтом»); the entire countryside had the solemn stillness of a summer night (торжественная тишина летней ночи окутала все вокруг; entire – полный, целый, весь; countryside – сельская местность; solemn – торжественный, производящий большое впечатление); our footfalls and the ceaseless song of the katydids were the only sound aloof (наши шаги и неумолчный: «беспрерывный» стрекот кузнечиков были единственными звуками в ночи; song – пение; katydid – /зоол./ кузнечик углокрылый; aloof – поодаль, в стороне). Black shadows of bordering trees lay athwart the road (черные тени деревьев на обочине наискосок ложились на дорогу; to border – обрамлять, окаймлять; border – граница), which, in the short reaches between, gleamed a ghostly white (которая отсвечивала призрачным белым /светом/ в коротких промежутках между тенями; reach – протягивание /руки/; пространство, протяжение; to gleam – светиться; мерцать). As we approached the gate to our dwelling (когда мы подошли к калитке /ведущей/ к нашему дому; to approach – подходить, приближаться), whose front was in shadow, and in which no light shone (чей фасад был в тени, а в окнах не было света: «и в котором не светился никакой свет»; to shine), my father suddenly stopped and clutched my arm (мой отец внезапно остановился и схватил мою руку), saying, hardly above his breath (едва слышно сказав; breath – дыхание; below one’s breath – тихо, шепотом; above one’s breath – чуть громче шепота):

“God! God! what is that (Боже, Боже, что это)?”

“I hear nothing,” I replied (я ничего не слышу, – ответил я).

“But see – see (но смотри, смотри же)!” he said, pointing along the road, directly ahead (сказал он, указывая на что-то вдоль дороги прямо перед нами).

I said: “Nothing is there (ничего там нет). Come, father, let us go in – you are ill (пойдем, отец, давай зайдем в дом – ты болен).”

One night, a few months after the dreadful event, my father and I walked home from the city. The full moon was about three hours above the eastern horizon; the entire countryside had the solemn stillness of a summer night; our footfalls and the ceaseless song of the katydids were the only sound aloof. Black shadows of bordering trees lay athwart the road, which, in the short reaches between, gleamed a ghostly white. As we approached the gate to our dwelling, whose front was in shadow, and in which no light shone, my father suddenly stopped and clutched my arm, saying, hardly above his breath:

“God! God! what is that?”“I hear nothing,” I replied.“But see – see!” he said, pointing along the road, directly ahead.I said: “Nothing is there. Come, father, let us go in – you are ill.”

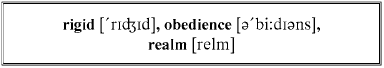

He had released my arm and was standing rigid and motionless in the center of the illuminated roadway (он отпустил мою руку и стоял, оцепенев, в центре залитой лунным светом дороги; rigid – жесткий, негнущийся, несгибаемый; неподвижный; motionless – неподвижный; motion – движение; to illuminate – освещать), staring like one bereft of sense (уставившись перед собой, как безумный; to stare – пристально глядеть; уставиться; смотреть в изумлении; to bereave – лишать, отнимать, отбирать; sense – рассудок, разум). His face in the moonlight showed a pallor and fixity inexpressibly distressing (бледность и неподвижность черт его лица в лунном свете казались невыразимо удручающими: «его лицо в лунном свете показывало бледность и неподвижность невыразимо горестные»). I pulled gently at his sleeve, but he had forgotten my existence (я тихонько потянул его за рукав, но он забыл о моем существовании; to forget). Presently he began to retire backward, step by step (вскоре он начал пятиться, шаг за шагом; to retire – уходить в отставку, на пенсию; удаляться, отступать; backward – назад), never for an instant removing his eyes from what he saw, or thought he saw (ни на миг не отрывая глаз от того, что он видел, или думал, что видел; to remove – передвигать, перемещать). I turned half round to follow, but stood irresolute (я наполовину обернулся, чтобы последовать /за ним/, но стоял в нерешительности). I do not recall any feeling of fear (я не помню, чтобы я чувствовал страх; to recall – вызывать обратно; вспоминать; воскрешать /в памяти/; feeling – чувство), unless a sudden chill was its physical manifestation (если только внезапный озноб не был его физическим проявлением). It seemed as if an icy wind had touched my face and enfolded my body from head to foot (казалось, словно ледяной ветер подул мне в лицо и окутал мое тело с головы до ног; to touch – касаться, трогать); I could feel the stir of it in my hair (я мог ощутить его дыхание в своих волосах; stir – шевеление; движение).

At that moment my attention was drawn to a light that suddenly streamed from an upper window of the house (в это мгновение мое внимание было отвлечено светом, что внезапно зажегся в окне верхнего этажа дома; to draw – тащить; тянуть, привлекать, притягивать; to stream – литься, струиться; stream – поток): one of the servants, awakened by what mysterious premonition of evil who can say (кто-то из прислуги, разбуженная кто знает: «кто может сказать» каким загадочным предчувствием зла), and in obedience to an impulse that she was never able to name, had lit a lamp (и повинуясь порыву, который она так и не смогла объяснить, зажгла лампу; to name – называть, назначать, указывать; name – имя). When I turned to look for my father he was gone (когда я обернулся посмотреть на моего отца, тот исчез; to look for – искать, разыскивать), and in all the years that have passed no whisper of his fate has come across the borderland of conjecture from the realm of the unknown (и за все прошедшие годы ни слуха о его судьбе не проникло через границу предположения из царства неведомого; to pass – идти, проходить; whisper – шепот; молва, слух).

He had released my arm and was standing rigid and motionless in the center of the illuminated roadway, staring like one bereft of sense. His face in the moonlight showed a pallor and fixity inexpressibly distressing. I pulled gently at his sleeve, but he had forgotten my existence. Presently he began to retire backward, step by step, never for an instant removing his eyes from what he saw, or thought he saw. I turned half round to follow, but stood irresolute. I do not recall any feeling of fear, unless a sudden chill was its physical manifestation. It seemed as if an icy wind had touched my face and enfolded my body from head to foot; I could feel the stir of it in my hair.

At that moment my attention was drawn to a light that suddenly streamed from an upper window of the house: one of the servants, awakened by what mysterious premonition of evil who can say, and in obedience to an impulse that she was never able to name, had lit a lamp. When I turned to look for my father he was gone, and in all the years that have passed no whisper of his fate has come across the borderland of conjecture from the realm of the unknown.

Назад: The Moonlit Road (Дорога, залитая лунным светом[10]) Ambrose Bierce (Амброз Бирс)

Дальше: II. Statement of Caspar Grattan (Cвидетельство Каспара Грэттена)