render() {

const { isLoading, todos } = this.state

if (isLoading) {

return h('p', {}, ['Loading...'])

}

return h('ul', {}, todos.map((todo) => h('li', {}, [todo])))

}

})

The first thing you’d naturally do is mock the fetch() function to return a promise that resolves with the data you want to test:

import { vi } from 'vitest'

// Mock the fetch API

global.fetch = vi.fn().mockResolvedValue({

json: vi.fn().mockResolvedValue([

'Feed the cat',

'Mow the lawn',

]),

})

That code had a little trick in it: fetch() returns a promise that resolves with a response object that has a json() method that returns a promise that resolves with the data.

That sentence is a mouthful, but the concept isn’t complicated. In any case, you’ve

14.1

Testing components with asynchronous behavior: nextTick()

323

already mocked the call to the server. To test that the loading indicator is rendered while the data is being fetched, you can do the following:

test('Shows the loading indicator while the todos are fetched', () => {

// If nextTick() isn't awaited for, the onMounted() hooks haven't run,

// so the loading should be displayed.

expect(document.body.innerHTML).toContain('Loading...')

})

It’s that easy! If you don’t await for the nextTick() function, the onMounted() hook hasn’t run yet, so the loading indicator is displayed. But at some point after the test has finished, the DOM will be updated and the loading indicator will disappear. You want to clean up the DOM after each test so that the next test starts with a clean DOM.

The only thing you need to do is await for the nextTick() function before unmounting the application, as shown in bold in the following snippet:

afterEach(async () => {

await nextTick()

Waits for the nextTick() function

app.unmount()

before unmounting the application

})

Note that if you had onUnmounted() asynchronous hooks, you’d also want to await for the nextTick() function after unmounting the application:

afterEach(async () => {

await nextTick()

app.unmount()

await nextTick()

})

To test that the list of to-dos is rendered after the data is fetched, you can do the following:

test('Shows the list of todos after the data is fetched', async () => {

// The nextTick() function is awaited for, so the onMounted() hooks

// have finished running, and the list of todos is displayed.

await nextTick()

expect(document.body.innerHTML).toContain('Feed the cat')

expect(document.body.innerHTML).toContain('Mow the lawn')

})

Waits for the nextTick() for the data to be

fetched and the component to re-render

A much better approach would be to add data-qa attributes to the elements in the DOM so that you can select them easily and then check their text content. But this example is simplified to show how to test components with asynchronous hooks.

324

CHAPTER 14

Testing asynchronous components

The same nextTick() function could test components that have asynchronous event handlers, such as a button that loads more data from a server when clicked, so you may wonder how you implement the nextTick() function. I’m glad you asked!

Let’s implement it. Make sure that you have a clear understanding of event loops, tasks, and microtask queues, because that knowledge is key to understanding what comes next. Buckle up!

14.1.2 The fundamentals behind the nextTick() function

The nextTick() function might appear to be magical, but it’s based on a solid understanding of the event loop’s mechanics. Some of the big frameworks implement similar functions, which are widely used for testing components with asynchronous behavior, so I’m positive that implementing your own function will help you understand how it works and when to use it.

The nextTick() function in some libraries

The nextTick() function defined in Vue can be used both in production code and in tests. Its usefulness resides in the fact that the code that you run after awaiting for the nextTick() function is executed after the component has re-rendered, when you know that the DOM has been updated. This function is documented at

. You can also check how it’s implemented in the runtime-core package, inside the scheduler.ts file,

Node JS implements a process.nextTick() function that’s used to schedule a callback to be executed on the next iteration of the event loop. You can find the documentation for it at I recommend that you give this documentation a read because it’s short and well explained.

Svelte defines a tick() function that returns a Promise that resolves when the component has re-rendered. Its use is similar to that of the nextTick() function in Vue.

This function is documented at You can check its implementation in the runtime.js file inside the internal/client/ folder at

The nextTick() function returns a Promise that resolves when all the pending jobs in the scheduler have finished executing. So the question is how you know when all the pending jobs in the scheduler have finished executing. First, you want to call the scheduleUpdate() function to make sure that when the nextTick() function is called, the processJobs() function is scheduled to run:

export function nextTick() {

scheduleUpdate()

// ...

}

If you remember from chapter 13, when the execution stack empties, the event loop executes all the microtasks first; then it executes the oldest task in the task queue, lets

14.1

Testing components with asynchronous behavior: nextTick()

325

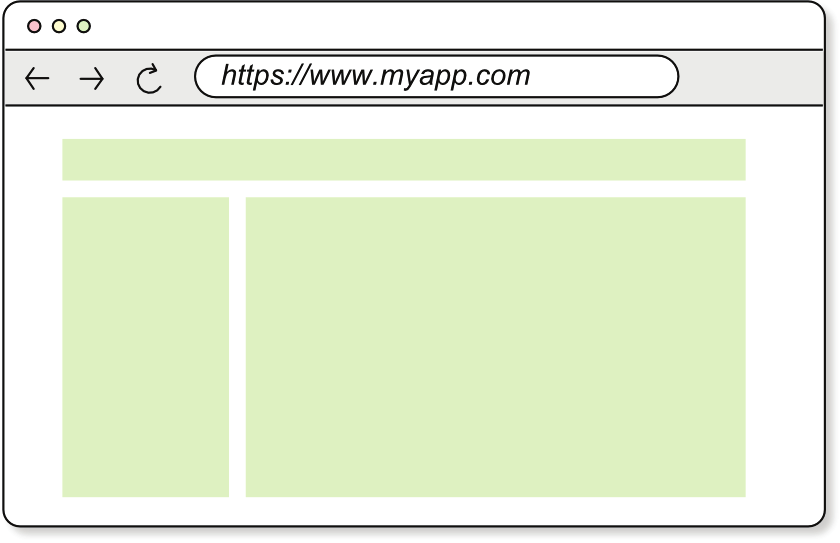

the DOM render, and starts over. You’ve queued the scheduleUpdate() function to run as a microtask, so you know that as soon as the execution stack is empty, the processJobs() function will be executed (figure 14.1).

When the execution stack empties, the

processJobs() function starts executing.

Microtasks

processJobs()

Ta

T sks

DOM

T1

T2

Execution stack

Event loop

Figure 14.1

The processJobs() function is scheduled to run as a microtask.

All the jobs in the scheduler are asynchronous because even if they weren’t originally, you’ve wrapped them inside a Promise and set up a then() callback to handle the result or rejection of the promise. As a result, the processJobs() function will queue more microtasks as it runs jobs (figure 14.2).

The processJobs() function schedules the

microtasks created by the jobs it executes.

Microtasks

job2()

μT1

μT2

μT3

job1()

Tasks

processJobs()

DOM

T1

T2

Execution stack

Event loop

Figure 14.2

The processJobs() function queues more microtasks.

The event loop won’t take the next task until all microtasks have been executed, including the microtasks that are queued by the processJobs() function. So to make sure that you resolve only the Promise returned by the nextTick() function when all the pending jobs in the scheduler finish executing, you need to schedule a task whose callback resolves the Promise returned by the nextTick() function. You can use setTimeout() to schedule a new task:

new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve))

326

CHAPTER 14

Testing asynchronous components

By scheduling the created Promise in the task callback, you’re forcing the event loop to go through at least another cycle before resolving the Promise because the resolve() function inside a Promise is scheduled as a microtask. So if the microtask is queued only when a task is executed, the event loop needs to process all pending microtasks, process the task that resolves the Promise, and then process all the pending microtasks until that resolve() is executed. Only then does awaiting for the Promise returned by the nextTick() function resolve (figure 14.3).

Other microtasks might be scheduled

This new microtask finishes after

before the resolve() task is executed.

every other scheduled microtask.

Microtasks

μT1

μT2

μT3

...

then()

Tasks

T1

T2

resolve()

Execution stack

Event loop

When this task is executed, it

enqueues a new microtask.

Figure 14.3

The Promise returned by the nextTick() function resolves when all the pending jobs in the scheduler have finished executing.

This process of scheduling a microtask via a task is commonly referred to as flushing promises. Many frontend and testing frameworks include a function to flush pending promises, mostly for testing purposes, so that you can easily write your unit tests without worrying about the asynchronous behavior of the components.

I know that this concept might be hard to wrap your head around, but you must understand how the event loop works to understand how the nextTick() function works. Take your time processing this information. If you need to, read this chapter again, draw the diagrams yourself, and experiment with the browser’s console. In section 14.1.3, I’ll ask you to do just that.

14.1.3 Implementing the nextTick() function

You should understand how the nextTick() function works by now, so you’re ready to implement it. Inside the scheduler.js file, add the code in listing 14.1.

Listing 14.1

nextTick() and flushPromises() (scheduler.js)

export function nextTick() {

scheduleUpdate()

return flushPromises()

}

14.1

Testing components with asynchronous behavior: nextTick()

327

function flushPromises() {

return new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve))

}

Before publishing the framework’s next version—version 4.1, including the nextTick() function—I want you to complete exercise 14.1. It challenges you to guess what the order of some console.log() calls will be—a classic JavaScript interview question—and will help you understand the principle behind the flushPromises() function.

Exercise 14.1

Open the browser’s console, and write this slightly modified version of the flushPromises() function:

function flushPromises() {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

console.log('setTimeout() with resolve() as callback...')

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('About to resolve the promise...')

resolve(42)

})

})

}

Note the two console logs:

One inside the Promise body, before the setTimeout() function is called

One inside the setTimeout() callback, right before the resolve() function is called

Now write this doWork() function, which schedules both microtasks and tasks and then awaits for the Promise returned by the flushPromises() function: async function doWork() {

queueMicrotask(() => console.log('Microtask 1'))

setTimeout(() => console.log('Task 1'))

queueMicrotask(() => console.log('Microtask 2'))

setTimeout(() => console.log('Task 2'))

const p = flushPromises()

queueMicrotask(() => {

console.log('Microtask 44')

queueMicrotask(() => console.log('Microtask 45'))

})

setTimeout(() => console.log('Task 22'))

const value = await p

console.log('Result of flush:', value)

}

328

CHAPTER 14

Testing asynchronous components

(continued)

Can you guess the order in which all these console.log() calls will be executed when you execute the doWork() function? Draw a diagram with the task and microtask queues to help you figure it out. Then run the doWork() function and compare the result with your expectations.

Find the solution .

14.2

Publishing version 4.1 of the framework

Let’s publish the new version of the framework. First, you want to include the nextTick() function as part of the public API of the framework. Including it allows developers to use this function inside their unit tests, as you saw in section 14.1. In the index.js file, add the import statement shown in bold:

export { createApp } from './app.js'

export { defineComponent } from './component.js'

export { DOM_TYPES, h, hFragment, hString } from './h.js'

export { nextTick } from './scheduler.js'

Then, in the package.json file, update the version number to 4.1.0:

"version": "4.0.0",

"version": "4.1.0",

Remember to move your terminal to the root or the project. Then run npm install so that the package version number in the package-lock.json file is updated: $ npm install

Finally, place your terminal inside the packages/runtime folder, and run $ npm publish

The new version of your framework, which includes the nextTick() function, is published.

14.3

Where to go from here

Congratulations on reaching the final chapter of the book! By now, you’ve achieved an impressive learning milestone. Your grasp of how frontend frameworks work sur-passes that of 99 percent of developers in this field. Even more remarkable, you’ve not only delved into the theory, but also mastered the practical aspect of frontends by building your own framework.

You may be eager to continue enhancing your skills. Consider adding a router to enable seamless transitions among pages and incorporating a template compiler into your build process. Perhaps you’re even contemplating creating a Chrome/Firefox

14.3

Where to go from here

329

extension to debug applications written with your framework. These features are common in frontend frameworks, and understanding how to implement them can further elevate your expertise. Originally, I intended to cover these topics in the book, but due to the book’s length constraints, they had to be omitted.

Nevertheless, I wanted to cover this material, so I had two options: write an extra part for this book or publish the material online. The second option seemed to be a better idea, so I’ve published some extra chapters in the wiki section of the book’s code repository ). I suggest that you continue your learning journey by reading the chapters in the wiki; they follow a similar structure to the chapters in this book, so you should feel right at home. The material covered in the wiki is more advanced, however, so be ready to embrace the challenge.

When you’ve finished reading the advanced extra chapters in the wiki, you’ll have a nice frontend framework of your own—one that you can try in your next project.

Build your portfolio with it, or create that side project you’ve been thinking about for a while. When you use your framework in a medium-size project, you’ll see its shortcomings. Maybe it isn’t as convenient to use as the big frameworks, for example, or it may be missing some features. Reflect on what features you could add to fix those shortcomings and then try to implement them. The process will be challenging (and fun). You’ll want to open the source code of other frameworks, read their documentation, and debug their code, which is how you learn.

The GitHub repository’s discussions section is a forum where you can propose new features for the framework, ask questions, and get help from the community so that we can learn from one another. If you have a great idea for a feature but don’t know how to implement it, or if you have several options but want help from the community to evaluate its tradeoffs, this section is the place to go. You can find it at

As in any other public forum where people with all levels of experience participate and ask for directions, please be respectful and kind. I know that you are a kind person with a big heart and willingness to help, so I don’t think you need to be reminded of this point. Also, value other people’s time, and don’t expect them to do your work for you. Take the time to do your research and pose your questions in a way that makes it easy for others to help you. You can read more about these guide-lines in the “how to ask” section of Stack Overflow

).

After reading this book, completing the advanced topics in the wiki, and building a project with your framework, you can go a step further and try the following:

Innovate—Do you have an idea for a new feature that would make your framework stand out from the rest? What’s stopping you from implementing it?

Collaborate in the development of a well-established framework such as Vue, React, Angular, or Svelte—These projects are open source, and they’re always looking for new contributors. You’ll need to get acquainted with the codebase first, but you have many of the core concepts already covered.

330

CHAPTER 14

Testing asynchronous components

Improve the performance of your framework—Do you need inspiration? Check out Inferno JS (Start by measuring the performance of the operations in your framework; you might need to look for some tooling. Then find the bottlenecks and think about how to get rid of them.

Write another framework from scratch—Make all the decisions yourself, weigh the tradeoffs, and learn from your mistakes. You can always come back to this book for reference, but this time, you’ll be the one making the decisions.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this book as much as I enjoyed writing it. This chapter is a goodbye from me, but I hope to see you in the discussions section of the repository or the issues section if you find a bug in the code. I wish you all the best in your learning journey, in your professional career, and, above all, in your life.

Summary

To test components with asynchronous hooks or event handlers, you need to await for the nextTick() function before checking what’s in the DOM.

The nextTick() function returns a Promise that resolves when all the pending jobs in the scheduler have finished executing.

To implement the nextTick() function, you need to schedule a task whose callback resolves the Promise returned by the nextTick() function.

appendix

Setting up the project

Before you write any code, you need to have an NPM project set up. In this appendix, I’ll help you create and configure a project to write the code for your framework.

I understand that you might not configure an NPM project from scratch with a bundler, a linter, and a test library, as most frameworks come with a command-line interface (CLI) tool (such as create-react-app or angular-cli) that creates the scaffolding and generates the boilerplate code structure. So I’ll give you two options to create your project:

Use the CLI tool I created for this book. With a single command, you can create a project and can start writing your code right away.

Configure the project from scratch. This option is more laborious, but it teaches you how to configure the project.

If you want to get started with the book quickly and can’t wait to write your awe-some frontend framework, I recommend that you use the CLI tool. In this case, you need to read section A.8. But if you’re the kind of developer who enjoys configuring everything from scratch, you can follow the steps in section A.9 to configure the project yourself.

Before you start configuring your project, I’ll cover some basics: where you can find the code for the book and the technologies you’ll use. These sections are optional, but I recommend that you read them before you start configuring your project. If you can’t wait to start writing code, you can skip them and move on to sections A.8 and A.9. You can always come back and read the rest of the appendix later.

331

332

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

A.1

Where to find the source code

The source code for the book is publicly available at I recommend that you clone the repository or download the zip archive of the repository so you can follow along with the book. The archive contains all the listings that appear in the book (in the listings folder), sorted by chapter. I’m assuming that you’re familiar with Git and know how to clone a repository and checkout tags or branches. If the previous sentence looks like nonsense to you, don’t worry; you can still follow along.

Download the project as a zip archive by clicking the <> Code button in the repository and then clicking the Download ZIP button.

WARNING

The code you’ll find in the repository is the final version of the framework—the one you’ll have written by the end of the book. If you want to check the code for each chapter, you need to check out the corresponding Git tag, as explained in the next section. You can also refer to the listings directory in the repository, which contains all the listings from the book sorted by chapter.

A.1.1

Checking out the code for each chapter

I tagged the source code with the number of each chapter where a new version of the framework is available. The tag name follows the pattern chX, where X is the number of the chapter. The first working version of the framework appears in chapter 6, for example, so the corresponding code can be checked out with the following Git command: $ git checkout ch6

Then, in chapters 7 and 8, you implement the reconciliation algorithm, resulting in a new version of the framework with enhanced performance. The corresponding code can be checked out as follows:

$ git checkout ch8

By checking out the code for each chapter, you can see how the framework evolves as we add features. You can also compare your code by the end of each chapter with the code in the repository. Note that not all chapters have a tag in the repository—only those that have a working version of the framework. I also wrote unit tests for the framework that I won’t cover in the book, but you can look at them to find ideas for testing your code.

NOTE

If you’re not familiar with the concept of Git tags, you can learn about them at . For this book, I assume that you have basic Git knowledge.

I recommend that you avoid copying and pasting the code from the book; instead, type it yourself. If you get stuck because your code doesn’t seem to work, look at the code in the repository, try to figure out the differences, and then fix the problem

A.1

Where to find the source code

333

yourself. If you write a unit test to reproduce the problem, so much the better. I know that this approach is more cumbersome, but it’s the best way to learn, and it’s how you’d probably want to tackle a real-world bug in your code. You can also refer to the listings/ directory in the repository, which contains all the listings from the book sorted by chapter.

You can find instructions for running and working with the code in the README

file of the repository (). This file contains up-to-date documentation on everything you need to know about the code. Make sure to read it before you work with the code. (When you start working with the code in an open source repository, reading the README file is the first thing you should do.)

A.1.2

A note on the code

I didn’t write the code to be the most performant and safest code possible. Many code snippets could use better error handling, or I could have done things in a more performant way by applying optimizations. But I emphasized writing code that’s easy to understand, clean, and concise—code that you read and immediately understand.

I pruned all the unnecessary details that would make code harder to understand and left in only the essence of the concept I want to teach. I went to great lengths to simplify the code as much as possible, and I hope you’ll find it easy to follow. But bear in mind that the code you’ll find in the repository and the book was written to teach a concept efficiently, not to be production-ready.

A.1.3

Reporting problems in the code

As many tests as I wrote and as many times as I reviewed the code, I’m sure that it still has bugs. Frontend frameworks are complex beasts, and it’s hard to get everything right. If you find a bug in the code, please report it in the repository by opening a new problem.

To open a new problem, go to the issues tab of the repository (

), and click the New Issue button. In the Bug Report row, click the Get Started button. Fill in the form with details on the bug you found, and click the Submit New Issue button.

You’ll need to provide enough information that I can easily reproduce and fix the bug. I know that it takes time to file a bug report with this many details, but it’s considered to be good etiquette in the open source community. Filing a detailed report shows respect to the people who maintain a project, who use their free time to create and maintain it for everyone to use free of charge. It’s good to get used to being a respectful citizen of the open source community.

A.1.4

Fixing a bug yourself

If you find a bug in the code and know how to fix it, you can open a pull request with the fix. Even better than opening a problem is offering a solution to it; that’s how open source projects work. You may also want to look at bugs that other people reported and

334

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

try to fix them. This practice is a great way to learn how to contribute to open source projects, and I’ll be forever grateful if you do so.

If you don’t know what GitHub pull requests are, I recommend that you read about them at Pull requests enable you to contribute to open source projects on GitHub, and also many software companies use them to add changes to their codebase, so it’s good to know how they work.

A.2

Solutions to the exercises

In most chapters of this book, I present exercises to test your understanding of the concepts I’ve explained. Some may seem to be straightforward, but others are challenging. If you want to absorb the concepts in the book, I recommend doing the exercises. Only if you get stuck or when you think you’ve found the solution should you check the answers. I’ve included the answers to all the exercises in the wiki of the repository:

In the wiki, you’ll find a page for the solutions to the exercises in the book by chapter:

The wiki includes extra chapters that cover advanced topics. These chapters didn’t make it into the book because the book would’ve been too long.

A.3

Advanced topics

When you finish this book, you’ll have a decent frontend framework—one that wouldn’t be suitable for large production applications but would work very well for small projects. The key is for you to learn how frontend frameworks work and have fun in the process. But you may want to continue learning and improving your framework. So I’ve written some extra chapters on advanced topics, which you can find in the repository’s wiki (section A.2). In these chapters, you’ll learn to

Add Typescript types to your framework bundle.

Add support for server-side rendering.

Write the templates in HTML and compile them to render functions.

Include external content inside your components (slots).

Create a browser extension to inspect the components of your application.

I hope that you enjoy these chapters, but you have to learn the basics first, so make sure that you finish this book with a solid understanding of the topics it covers.

A.4

Note on the technologies used

There are heated discussions in the frontend ecosystem about the best tools. You’ll hear things like “You should use Bun because it’s much faster than Node JS” and

A.4

Note on the technologies used

335

“Webpack is old now; you should start using Vite for all your projects.” Some people argue about which bundler is best or which linter and transpiler you should be using.

I find blog posts of the “top 10 reasons why you should stop using X” kind to be especially harmful. Apart from being obvious clickbait, they usually don’t help the frontend community, let alone junior developers who have a hard time understanding what set of tools they “should” be using.

A cautionary tale on getting overly attached to tools

I once worked for a startup that grew quickly but wasn’t doing well. Very few customers used our app, and every time we added something to the code, we introduced new bugs. (Code quality wasn’t a priority; speed was. Automated testing was nowhere to be found.) Surprisingly, we blamed the problem on the tools we were using. We were convinced that when we migrated the code to the newest version of the framework, we got more customers, and things worked well from then on. Yes, I know that belief sounds ridiculous now, but we made it to “modernize” the tooling.

Guess what? The code was still the same: a hard-to-maintain mess that broke if you stared at it too long. It turns out that using modern tools doesn’t make code better if the code is poorly written in the first place.

What do I want to say here? I believe that your time is better used writing quality code than arguing about what tools will make your application successful. Well-architected and modularized code with a great suite of automated tests that, apart from making sure that the code works and can be refactored safely, also serves as documentation, beats any tooling. That isn’t to say that the tools don’t matter because they obviously do. Ask a carpenter whether they can be productive using a rusty hammer or a blunt saw.

For this book, I tried to choose tools that are mature and that most frontend developers are familiar with. Choosing the newest, shiniest, or trendiest tool wasn’t my goal. I want to teach you how frontend frameworks work, and the truth is that most tools work perfectly well for this purpose. The knowledge that I’ll give you in this book tran-scends the tools you choose to use. If you prefer a certain tool and have experience with it, feel free to use it instead of the ones I recommend here.

A.4.1

Package manager: NPM

We’ll use the NPM package manager () to create the project and run the scripts. If you’re more comfortable with yarn or pnpm, you can use them instead. These tools work very similarly, so you shouldn’t have any problem using the one you prefer.

We’ll use NPM workspaces (

, which were introduced in version 7. Make sure that you have at least version 7

installed:

$ npm --version

8.19.2

336

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

Both yarn and pnpm support workspaces, so you can use them as well. In fact, they introduced workspaces before NPM did.

A.4.2

Bundler: Rollup

To bundle the JavaScript code into a single file, we’ll use Rollup (), which is simple to use. If you prefer Webpack, Parcel, or Vite, however, you can use it instead. You’ll have to make sure that you configure the tool to output a single ESM

file (as you’ll see).

A.4.3

Linter: ESLint

To lint the code, we’ll use ESLint (a popular linter that’s easy to configure. I’m a firm believer that static analysis tools are musts for any serious project in which code quality is important (as it always is).

ESLint prevents us from declaring unused variables, having unused imports, and doing many other things that cause problems in code. ESLint is super-configurable, but most developers are happy with the default configuration, which is a good starting point. We’ll use the default configuration in this book as well, but you can always change it to your liking. If you deem a particular linting rule to be important, you can add it to your configuration.

A.4.4

(Optional) Testing: Vitest

I won’t be showing unit tests for the code you’ll write in this book to keep its size reasonable, but if you check the source code of the framework I wrote for the book, you’ll see lots of them. (You can use them to better understand how the framework works. When they’re well written, tests are great sources of documentation.) You may want to write tests yourself to make sure that the framework works as expected and that you don’t break it when you make changes. Every serious project should be accompanied by tests, which serve as a safety net as well as documentation.

I’ve worked a lot with Jest which has been my go-to testing framework for a long time. But I recently started using Vitest and decided to stick with it because it’s orders of magnitude faster. Vitest’s API is similar to Jest’s, so you won’t have problems if you decide to use it as well. But if you want to use Jest, it’ll do fine.

A.4.5

Language: JavaScript

Saying that we’ll use JavaScript may seem to be obvious, but if I were writing the framework for myself, I’d use TypeScript without hesitation. TypeScript is fantastic for large projects: types tell you a lot about the code, and the compiler will help you catch bugs before you even run the code. (How many times have you accessed a property that didn’t exist in an object using JavaScript? Does TypeError sends shivers down your spine?) Nontyped languages are great for scripting, but for large projects, I recommend having a compiler as your companion.

A.6

Structure of the project

337

Why, then, am I using JavaScript for this book? The code tends to be shorter without types, and I want to teach you the principles of how frontend frameworks work—

principles that apply equally well to JavaScript and TypeScript. I prefer to use JavaScript because the code listings are shorter and I can get to the point faster, thus teaching you more efficiently.

As with the previous tools, if you feel strongly about using TypeScript, you can use it instead of JavaScript. You’ll need to figure out the types yourself, but that’s part of the fun, right? Also, don’t forget to set up the compilation step in your build process.

A.5

Read the docs

Explaining how to configure the tools you’ll use in detail, as well as how they work, is beyond the scope of this book. I want to encourage you to go to the tools’ websites or repository pages and read the documentation. One great aspect of frontend tools is that they tend to be extremely well documented. I’m convinced that the makers compete against one another to see which one has the best documentation.

If you’re not familiar with any of the tools you’ll be using, take some time to read the documentation, which will save you a lot of time in the long run. I’m a firm believer that developers should strive to understand the tools they use, not just use them blindly.

(That belief is what encouraged me to learn how frontend frameworks work in the first place, which explains why I’m writing this book.)

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned over the years is that taking time to read the documentation is a great investment. Reading the docs before you start using a new tool or library saves you the time you’d spend trying to figure out how to do something that the documentation explains in detail. The time you spend trying to figure things out and searching StackOverflow for answers, is (in my experience) usually greater than the time you’d have spent reading the documentation up front.

6 hours of debugging can save you 5 minutes of reading documentation

— Jakob (@jcsrb)Twitter

Be a good developer; read the docs. (Or at least ask ChatGPT a well-structured question.)

A.6

Structure of the project

Let’s briefly go over the structure of the project in which you’ll write the code for your framework. The framework that you’ll write in this book consists of a single package (NPM workspace): runtime. This package is the framework itself.

NOTE

The advanced chapters you can read in the repository’s wiki add more packages to the project. For this reason, you want to structure your project by using NPM workspaces. It may seem silly to use workspaces when the project consists of a single package, but this approach will make sense when you add packages to the project.

338

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

TIP

If you’re not familiar with NPM workspaces, you can read about them at

It’s important to understand how they work so that the structure of the project makes sense and you can follow the instructions.

The folder structure of the project is as follows:

examples/

packages/

└── runtime/

When you add packages (advanced chapters in the repository), they’ll be inside the packages directory as well:

examples/

packages/

├── compiler/

├── loader/

└── runtime/

Each package has its own package.json file, with its own dependencies, and is bundled separately. The packages are effectively three separate projects, but they’re all part of the same repository. This project structure is common these days; it’s called a monorepo. The packages you include will define the same scripts:

build—Builds the package, bundling all the JavaScript files into a single file, which is published to NPM.

test—Runs the automated tests in watch mode.

test:run—Runs the automated tests once.

lint—Runs the linter to detect problems in your code.

lint:fix—Runs the linter and automatically fixes the problems it can fix.

prepack—A special lifecycle script ) that runs before the package is published to NPM. It’s used to ensure that the package is built before being published.

WARNING

The aforementioned scripts are defined in each of the three pack-

ages’ package.json files (packages/runtime, for example), not in the root package.json file. Bear this fact in mind in case you decide to configure the project yourself because there will be two package.json files total, plus one package that you add to the project.

A.7

Finding a name for your framework

Before you create the project or write any code, you need a name for your framework.

Be creative! The name needs to be one that no one else is using in NPM (where you’ll be publishing your framework), so it must be original. If you’re not sure what to call it, you can simply call it <your name>-fe-fwk (your name followed by -fe-fwk). To make sure

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

339

that the name is unique, check whether it’s available on npmjs.com (

) by adding it to the URL, as follows: www.npmjs.com/package/ <your framework name>

If the URL displays the 404—not found error page, nobody is using that name for a Node JS package yet, so you’re good to go.

NOTE

I’ll use the <fwk-name> placeholder to refer to the name of your framework in the sections that follow. Whenever you see <fwk-name> in a command, you should replace it with the name you chose for your framework.

Now let’s create the project. Remember that you have two options. If you want to configure things yourself, jump to section A.9. If you want to use the CLI tool to get started quickly, read section A.8.

A.8

Option A: Using the CLI tool

Using the CLI tool I created for the book is the fastest way to get started. This tool will save you the time it takes to create and configure the project from scratch, so you can start writing code right away. Open your terminal, move to the directory where you want the project to be created, and run the following command:

$ npx fe-fwk-cli init <fwk-name>

With npx, you don’t need to install the CLI tool locally; it will be downloaded and executed automatically. When the command finishes executing, it instructs you to cd in to the project directory and run npm install to install the dependencies: $ cd <fwk-name>

$ npm install

That’s it! Go to section A.10 to learn how to publish your framework to NPM.

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

NOTE

If you created your project by using the CLI tool, you can skip this section.

To create the project yourself, first create a directory for it. On the command line, run the following command:

$ mkdir <fwk-name>

Then initialize an NPM project in that directory:

$ cd <fwk-name>

$ npm init -y

340

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

This command creates a package.json file in the directory. You need to make a few edits in the file. For one, you want to edit the description field to something like

"description": "A project to learn how to write a frontend framework"

Then you want to make this package private so that you don’t accidentally publish it to NPM (because you’ll publish the workspace packages to NPM, not the parent project):

"private": true

You also want to change the name of this package to <fwk-name>-project to prevent con-flicts with the name of your framework (which you’ll use to name the runtime package you create in section A.10). Every NPM package in the repository requires a unique name, and you want to reserve the name you chose for your framework for the runtime package. So append -project to the name field:

"name": "< fwk-name> -project"

Finally, add a workspaces field to the file, with an array of the directories where you’ll create the packages that comprise your project (so far, only the runtime package):

"workspaces": [

"packages/runtime"

]

Your package.json file should look similar to this:

{

"name": "< fwk-name>- project",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "A project to learn how to write a frontend framework",

"private": true,

"workspaces": [

"packages/runtime"

]

}

You may have other fields—author, license, and so on—but the ones in the preceding snippet are the ones that must be there. Next, let’s create a directory in your project where you can add example applications to test your framework.

A.9.1

The examples folder

Throughout the book, you’ll be improving your framework and adding features to it.

Each time you add a feature, you’ll want to test it by using it in example applications.

Here, you’ll configure a directory where you can add these applications and a script to serve them locally. Create an examples directory at the root of your project: $ mkdir examples

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

341

TIP

While the examples folder remains empty—that is, before you write any example application—you may want to add a .gitkeep file to it so that Git picks up the directory and includes it in the repository. (Git doesn’t track empty directories.) As soon as you put a file in the directory, you can remove the .gitkeep file, but keeping it doesn’t hurt.

To keep the examples directory tidy, create a subdirectory for each chapter: examples/ch02, examples/ch03, and so on. Each subdirectory will contain the example applications using the framework resulting from the chapter, which allows you to see the framework become more powerful and easier to use. You don’t need to create the subdirectories now; you’ll create them as you need them in the book.

Now you need a script to serve the example applications. Your applications will consist of an entry HTML file, which loads other files, such as JavaScript files, CSS

files, and images. For the browser to load these files, you need to serve them from a web server. The http-server package is a simple web server that can serve the example applications. In the package.json file, add the following script:

"scripts": {

"serve:examples": "npx http-server . -o ./examples/"

}

NOTE

This script is the only one you need to add to the project root package.json file. All the other scripts will be added to the package.json files of the packages you’ll create in the following sections. You won’t add any other script to the root package.json file.

The project doesn’t require the http-server package to be installed, as you’re using npx to run it. The -o flag tells the server to open the browser and navigate to the specified directory—in the case of the preceding command, the examples directory. Your project should have the following structure so far:

<fwk-name> /

├── package.json

└── examples/

└── .gitkeep

Great. Now let’s create the three packages that will make up your framework code.

A.9.2

Creating the runtime package

As I’ve said, your framework will consist of a single package: runtime. In the advanced chapters published in the repository’s wiki (section A.2), you’ll add packages to the project, but for now, you’ll create only the runtime package.

Before you create the package, you need to create a directory where you’ll put it: the packages directory you specified in the workspaces field of the package.json file.

Make sure that your terminal is inside the project’s root directory by running the pwd command:

$ pwd

342

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

The output should be similar to this (where path/to/your/framework is the path to the directory where you created the project):

path/to/your/framework/ <fwk-name>

If your terminal isn’t in the project’s root directory, use the cd command to navigate to it. Then create a packages directory:

$ mkdir packages

THE RUNTIME PACKAGE

Let’s create the runtime package. First, cd into the packages folder: $ cd packages

Then create the folder for the runtime package and cd into it:

$ mkdir runtime

$ cd runtime

Next, initialize an NPM project in the runtime folder:

$ npm init -y

Open the package.json file that was created for you, and make sure that the following fields have the right values (leaving the other fields as they are):

{

"name": " <fwk-name> ",

"version": "1.0.0",

"main": "dist/ <fwk-name> .js",

"files": [

"dist/ <fwk-name> .js"

]

}

Remember to replace <fwk-name> with the name of your framework. The main field specifies the entry point of the package, which is the file that will be loaded when you import the package. When you import code from this package as follows, import { something } from ' <fwk-name> '

JavaScript resolves the path to the file specified in the main field. You’ve told NPM that the file is the dist/< fwk-name>.js file, which is the bundled file containing all the code for the runtime package. Rollup will generate this file when you run the build script you’ll add to the package.json file in the next section.

The files field specifies the files that will be included in the package when you publish it to the NPM repository. The only file you want to include is the bundled file, so you’ve specified that in the files field. Files like README, LICENSE, and

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

343

package.json are automatically included in the package, so you don’t need to include them. Your project should have the following structure (the parts in bold are the ones you just created):

<fwk-name> /

├── package.json

├── examples/

│ └── .gitkeep

└── packages/

└── runtime/

└── package.json

INSTALLING AND CONFIGURING ROLLUP

Let’s add Rollup to bundle the framework code. Rollup is the bundler that you’ll use to bundle your framework code; it’s simple to configure and use. To install Rollup, make sure that your terminal is inside the runtime package directory by running the pwd command:

$ pwd

The output should be similar to

path/to/your/framework/ <fwk-name> packages/runtime

If your terminal isn’t inside the packages/runtime directory, use the cd command to navigate to it. Then install the rollup package by running the following command: $ npm install --save-dev rollup

You also want to install two plugins for Rollup:

rollup-plugin-cleanup—To remove comments from the generated bundle

rollup-plugin-filesize—To display the size of the generated bundle Install these plugins with the following command:

$ npm install --save-dev rollup-plugin-cleanup rollup-plugin-filesize Now you need to configure Rollup. Create a rollup.config.mjs file in the runtime folder. (Note the .mjs extension, which tells Node JS that this file should be treated as an ES module and thus can use the import syntax.) Then add the following code: import cleanup from 'rollup-plugin-cleanup'

import filesize from 'rollup-plugin-filesize'

export default {

Entry point of the

input: 'src/index.js',

framework code

plugins: [cleanup()],

Removes comments from

output: [

the generated bundle

{

344

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

file: 'dist/ <fwk-name> .js',

Name of the

format: 'esm',

generated bundle

plugins: [filesize()],

},

Formats the bundle

],

Displays the size of the

as an ES module

}

generated bundle

The configuration, explained in plain English, means the following:

The entry point of the framework code is the src/index.js file. Starting from this file, Rollup will bundle all the code that is imported from it.

The comments in the source code should be removed from the generated bundle; they occupy space and aren’t necessary for the code to execute. The plugin-rollup-cleanup plugin does this job.

The generated bundle should be an ES module (using import/export syntax, supported by all major browsers) that is saved in the dist folder as < fwk-name>.js.

We want the size of the generated bundle to be displayed in the terminal so we can keep an eye on it and make sure that it doesn’t grow too much. The plugin-rollup-filesize plugin does this job.

Now add a script to the package.json file (the one inside the runtime package) to run Rollup and bundle all the code, and add another one to run it automatically before publishing the package:

"scripts": {

"prepack": "npm run build",

"build": "rollup -c"

}

The prepack script is a special script that NPM runs automatically before you publish the package (by running the npm publish command). This script makes sure that whenever you publish a new version of the package, the bundle is generated. The prepack script simply runs the build script, which in turn runs Rollup.

To run Rollup, call the rollup command and pass the -c flag to tell it to use the rollup.config.mjs file as configuration. (If you don’t pass a specific file to the -c flag, Rollup looks for a rollup.config.js or rollup.config.mjs file.)

Before you test the build command, you need to create the src/ folder and the src/index.js file with the following commands:

$ mkdir src

$ touch src/index.js

NOTE

In Windows Shell, touch won’t work; use call > filename instead.

Inside the src/index.js file, add the following code:

console.log('This will soon be a frontend framework!')

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

345

Now run the build command to bundle the code:

$ npm run build

This command processes all the files imported from the src/index.js file (none at the moment) and bundles them into the dist folder. The output in your terminal should look similar to the following:

src/index.js → dist/ <fwk-name> .js...

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Destination: dist/ <fwk-name> .js │

│ Bundle Size: 56 B │

│ Minified Size: 55 B │

│ Gzipped Size: 73 B │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

created dist/ <fwk-name> .js in 62ms

Recall that instead of <fwk-name> , you should use the name of your framework. That rectangle in the middle of the output is the rollup-plugin-filesize plugin in action. It’s reporting the size of the generated bundle (56 bytes, in this case), as well as the size it would be if the file were minified and gzipped. We won’t be minifying the code for this book, as the framework is going to be small, but for a production-ready framework, you should do that. A browser can load minified JavaScript faster and thus improve the Time to Interactive (TTI; metric of the web application that uses it.

A new file, dist/< fwk-name>.js, has been created in the dist folder. If you open it, you’ll see that it contains only the console.log() statement you added to the src/

index.js file.

Great! Let’s install and configure ESLint.

INSTALLING AND CONFIGURING ESLINT

ESLint is a linter that helps you write better code; it analyzes the code you write and reports any errors or potential problems. To install ESLint, run the following command: $ npm install --save-dev eslint

You’ll use the ESLint recommended configuration, which is a set of rules that ESLint enforces in your code. Create the .eslintrc.js file inside the packages/runtime directory with the following content:

module.exports = {

env: {

browser: true,

es2021: true,

},

extends: 'eslint:recommended',

overrides: [],

346

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

parserOptions: {

ecmaVersion: 'latest',

sourceType: 'module',

},

rules: {},

}

Finally, add the following two scripts to the package.json file:

"scripts": {

"prepack": "npm run build",

"build": "rollup -c",

"lint": "eslint src",

"lint:fix": "eslint src --fix"

}

You can run the lint script to check the code for errors and the lint:fix script to fix some of them automatically—those that ESLint knows how to fix. I won’t show the output of the lint script in the book, but you can run it yourself to see what it reports as you write your code.

INSTALLING VITEST (OPTIONAL)

As I’ve mentioned, I used a lot of tests while developing the code for this book, but I won’t be showing them in the book. You can find them in the source code of the framework and try to write your own as you follow along. Having tests in your code will help you ensure that things work as expected as you move forward with the development of your framework. We’ll use Vitest to run the tests. To install Vitest, run the following command:

$ npm install --save-dev vitest

Tests can run in different environments, such as Node JS, JSDOM, or a real browser.

Because we’ll use the Document API to create Document Object Model (DOM) elements, we’ll use JSDOM as the environment. (If you want to know more about JSDOM, see its repository: .) To install JSDOM, run the following command:

$ npm install --save-dev jsdom

With Vitest and JSDOM installed, you can create the vitest.config.js file with the following content:

import { defineConfig } from 'vitest/config'

export default defineConfig({

test: {

reporters: 'verbose',

environment: 'jsdom',

},

})

A.9

Option B: Configuring the project from scratch

347

This configuration tells Vitest to use the JSDOM environment and the verbose reporter, which outputs a descriptive report of the tests.

You should place your test files inside the src/__tests__ folder and name them

*.test.js so that Vitest can find them. Create the src/__tests__ folder: $ mkdir src/__tests__

Inside, create a sample.test.js file with the following content:

import { expect, test } from 'vitest'

test('sample test', () => {

expect(1).toBe(1)

})

Now add the following two scripts to the package.json file:

"scripts": {

"prepack": "npm run build",

"build": "rollup -c",

"lint": "eslint src",

"lint:fix": "eslint src --fix",

"test": "vitest",

"test:run": "vitest run"

}

The test script runs the tests in watch mode, and the test:run script runs the tests once and exits. Tests in watch mode are handy when you’re working with test-driven development, as they run every time you change the test file or the code you’re testing. Try the tests by running the following command:

$ npm run test:run

You should see the following output:

✓ src/__tests__/sample.test.js (1)

✓ sample test

Test Files 1 passed (1)

Tests 1 passed (1)

Start at 15:50:11

Duration 1.47s (transform 436ms, setup 1ms, collect 20ms, tests 3ms) You can run individual tests by passing the name or path of the test file as an argument to the test:run and test scripts. All the tests that match the name or path will be run. To run the sample.test.js test, for example, issue the following command: $ npm run test:run sample

This command runs only the sample.test.js test and produces the following output:

348

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

✓ src/__tests__/sample.test.js (1)

✓ sample test

Test Files 1 passed (1)

Tests 1 passed (1)

Start at 15:55:42

Duration 1.28s (transform 429ms, setup 0ms, collect 32ms, tests 3ms) Your project structure should look like the following at this point (the files and folders that you’ve created are in bold):

<fwk-name> /

├── package.json

├── examples/

│ └── .gitkeep

└── packages/

└── runtime/

├── package.json

├── rollup.config.mjs

├── .eslintrc.js

├── vitest.config.js

└── src/

├── index.js

└── __tests__/

└── sample.test.js

Your runtime package is ready for you, and you can start writing code. Next, let’s see how you can publish it to NPM.

A.10

Publishing your framework to NPM

As exciting as it is to develop your own framework, it’s even more exciting to share it with the world. NPM allows us to ship a package with one simple command: $ npm publish

But first, you need to create an account on NPM and log in to it from the command line. If you don’t plan to publish your framework, you can skip the next section.

A.10.1 Creating an NPM account

To create an NPM account, go to and fill out the form. It’s simple, and it’s free.

A.10.2 Logging in to NPM

To log in to NPM in your terminal, run the command

$ npm login

and follow the prompts. To make sure that you’re logged in, run the following command: $ npm whoami

A.10

Publishing your framework to NPM

349

You should see your username printed in the terminal.

A.10.3 Publishing your framework

To publish your framework, you need to make sure that your terminal is in the right directory, inside packages/runtime:

$ cd packages/runtime

Your terminal’s working directory should be packages/runtime (in bold):

<fwk-name> /

├── package.json

├── examples/

│ └── .gitkeep

Your terminal’s

working directory

└── packages/

should be here.

├── runtime/

├── compiler/

└── loader/

WARNING

Make sure that you’re not in the root folder of the project. The root folder’s package.json file has the private field set to true, which means that it’s not meant to be published to NPM. The runtime package is what you want to publish to NPM.

NOTE

Remember that the runtime package is the code for the framework (what you want to publish), and the root of the project is the monorepo containing the runtime and other packages (not to be published to NPM).

With your terminal in the runtime directory, run the following command: $ npm publish

You may wonder what gets published to NPM. Some files in your project always get published: package.json, README.md, and LICENSE. You can specify which files to publish in the files field of the package.json file. If you recall, the files field in the package.json file of the runtime package looks like this:

"files": [

"dist/ <fwk-name> .js"

],

You’re publishing only the dist/< fwk-name>.js file, the bundled version of your framework. The source files inside the src/ folder are not published.

The package is published with the version specified in the package.json file’s version field. Bear in mind that you can’t publish a package with the same version twice. Throughout the book, we’ll increment the version number every time we publish a new version of the framework.

350

APPENDIX

Setting up the project

A.11

Using a CDN to import the framework

After you’ve published your framework to NPM, you can create a Node JS project and install it as a dependency:

$ npm install <fwk-name>

This approach is great if you plan to set up an NPM project with a bundler (such as Rollup or Webpack) configured to bundle your application and the framework together, which you typically do when you’re building a production application with a frontend framework. But for small projects or quick experiments that use only a few files—like those you’ll work on in this book—it’s simpler to import the framework directly from the dist/ directory in your project or from a content-delivery network (CDN).

One free CDN that you can use is unpkg Everything that’s published to NPM is also available on unpkg.com, so after you’ve published your framework to NPM, you can import it from there:

import { createApp, h } from 'https://unpkg.com/ <fwk-name> '

If you browse to you’ll see the dist/< fwk-name>.js file you published in NPM, which the CDN serves to your browser when you import the framework from there. If you don’t specify a version, the CDN serves the latest version of the package. If you want to use a specific version of your framework, you can specify it in the URL:

import { createApp, h } from 'https://unpkg.com/ <fwk-name> @1.0.0'

Or if you want to use the last minor version of the framework, you can request a major version:

import { createApp, h } from 'https://unpkg.com/ <fwk-name> @1'

I recommend that you use unpkg with the versioned URL so you don’t have to worry about changes in the framework that might break your examples as you publish new versions. If you import the framework directly from the dist folder in your project, every time you bundle a new version that’s not backward-compatible, your example applications will break. You could overcome this problem by instructing Rollup to include the framework version in the bundled filename, but I’ll be using unpkg in this book.

You’re all set! It’s time to start developing your framework. You can turn to chapter 2 to start the exciting adventure that’s ahead of you.

index

Symbols

areNodesEqual() function , ,

arguments object

!= operator

arrayDiffSequence() function

=== operator

#array property

== operator

arrays, diffing

arraysDiff() function

Numerics

arraysDiffSequence() function

adding item to old array

404 error page

addition case

move case

A

noop case

remove case

action attribute

removing outstanding items

add() method

TODO comments

addedListeners variable

ArrayWithOriginalIndices class

addEventHandler() method

addEventListener() function , async/await

asynchronous components, testing

addEventListener() method

nextTick() function

addItem() method

fundamentals behind

addition case

implementing

add operation

testing components with asynchronous

addProps() function

onMounted() hook

addTodo() function ,

publishing version 4.1 of framework

after-command handlers

attributes object

afterEveryCommand() function

attrs property

afterEveryCommand() method

await function

App() component

await keyword

App() function

append() method

B

application, mounting

application instance

BarComponent

.apply() method

<body> tag, cleaning up

applyArraysDiffSequence() function

browser side of SPAs

351

352

INDEX

browser side of SSR applications

updating state and patching DOM

btn class

omponents; stateless compo-btnClicked event

nents

build command

conditional rendering

build script

element nodes

<button> element

mapping strings to text nodes

null values, removing

C

console.log() function

console.log() statement

call() function

consumer function

call stack

Counter component

catch() function

count property

cd command

count state property

CDN (content-delivery network)

createApp() function ,

-c flag

ch8 label

createComponentNode() function , checkWinner() function

child nodes, patching

created state

childNodes array

createElement() function

children array

createElement() method

children property

createElementNode() function ,

class attribute

classList property

createFragmentNodes() function

className property

class property

createTextNode() function

click event

createTextNode() method

click event handler

CreateTodo() component –

CLI (command-line interface)

CreateTodo() function

color property

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets), loading files

commands

CSS class, patching

Component class , CSSStyleDeclaration object

cssText property

COMPONENT constant

component lifecycle hooks

D

event loop cycle

scheduler

dblclick event

component methods

debounce() function

component nodes, equality

declarative code

Component prototype

defineComponent() function

components

adding as new virtual DOM type

and components with state

mounting component virtual nodes

basic component methods

updating elements getter

checking whether component is already

as classes

mounted

as function of state

described

binding event handlers to

description field

composing views

destroyDOM() function

keeping track of mounting state of

offset

destroying element

overview of

destroying fragment

patching DOM using component’s offset

destroying virtual DOM

framework building and publishing

INDEX

353

destroyDOM() method

E

destroyed state

developers, frontend frameworks

ECMAScript (ES) modules

diffSeq

Element class

directives

element nodes

disabled attribute

extending solution to

disabled key

mapping strings to text nodes

:disabled pseudoclass

null values, removing

dispatch() function

elements, destroying

dispatch() method

elements getter

dispatcher

updating

assigning handlers to commands

el property

dispatching commands

el reference

notifying renderer about state changes

emit() function

Dispatcher class –

emit() method

:enabled pseudoclass

dispatcher property

enqueueJob() function

dispatcher variable

eqeqeq rule

div element

equalsFn parameter

Document API

ES (ECMAScript) modules

document.createDocumentFragment()

ESLint, installing and configuring

method

eslint-plugin-no-floating-promise plugin

document.createElement() function

event handlers

document.createElement() method

binding to components

document.createTextNode() method

context

DocumentFragment class

#eventHandlers object

document.getElementById() function

#eventHandlers property

DOM (Document Object Model)

event listeners, patching

event loop

destroying

event loop cycle

elements

scheduler

fragments

events

text nodes

communication via, patching component virtual

element nodes

nodes

keyed lists, extending solution to element

emitting events

nodes

extracting props and events for component

mounting

saving event handlers inside component

element nodes

fragment nodes

vs. callbacks

insert() function

vs. commands

text nodes

wiring event handlers

with host component

EventTarget interface

patching

execution stack

with host component

extractPropsAndEvents() function , separating concerns

virtual DOM, mounting

DOMTokenList object

F

DOM_TYPES.COMPONENT

DOM_TYPES constant

fastDeepEqual() function

DOM_TYPES object

fast-deep-equal library

doWork() function

fetch() function

files field

354

INDEX

findIndexFrom() method

handlers, assigning to commands

flatMap() method

hasOwnProperty() function

flushPromises() function

hasOwnProperty() method

FooComponent

Header component

Footer component

hFragment() function

for loop

higher-level application code

fragment nodes

hostComponent

implementing

host component

fragments, destroying

mounting DOM with

frameworks

patching DOM with

assembling state manager into

hostComponent argument

application instance

hostComponent parameter

application instance’s renderer

hostComponent reference

application instance’s state manager

hostElement reference

components dispatching commands

hString() function

unmounting application

HTMLElement class

building and publishing

HTMLElement instance

component lifecycle hooks and scheduler

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language)

finding name for

hydrating pages

frontend web framework, lifecycle hooks

loading files

loading pages

importing with CDN

HTML markup

publishing

HTMLParagraphElement class

short example

HTMLUnknownElement

publishing to NPM

http-server package

creating NPM account

hydration

logging in to NPM

HYPERLINK

publishing framework

hyperscript() function

publishing version 4 of

from property

I

frontend frameworks

building

id attribute

features

id property

implementation plan

imperative code

finding name for

importing framework, with CDN

overview of

import statement

browser and server sides of SSR

indexOf() function

applications

index parameter

browser side of SPAs

index property

developer’s side

initializing views

reasons for building

<input> element

orks

input event

insert() function

G

insertBefore() method

isAddition() method

global application state

#isMounted property

Greetings component

isNoop() method

isRemoval() method

H

isScheduled Boolean variable

isScheduled flag

h() function

item property

items prop

INDEX

355

J

List component

listeners object

JavaScript, loading files

listeners property

JavaScript code

ListItem component

adding, removing, and updating to-dos

loading state

initializing views

loadMore() method

rendering to-dos in edit mode

low-level operation

rendering to-dos in read mode

Jest

M

job() function

json() method

Main component

main field

K

mapTextNodes() function

max key

key attribute

MessageComponent() function

component nodes equality

methods

removing from props object

binding event handlers to components

using

keydown event

component

keyed lists

component methods

application instance

mounting DOM with host component

extending solution to element nodes

microtasks

minified files

key attribute

min key

component nodes equality

monorepo

removing from props object

mount() function

using

mount() method , using index as key

using same key for different elements

mountDOM() function ,

key prop

changes in rendering

component lifecycle

L

mountDOM() example

mounting component virtual nodes

<label> element

mounting virtual DOM

lazy-loading

scheduler ,

lexically scoped

scheduling lifecycle hooks execution

libraries

with host component

li elements

mounted state

lifecycle hooks

move case

asynchronicity

moveItem() method

execution context

move operation

mounted and unmounted

MyFancyButton component

overview

scheduler

N

simple solution that doesn’t quite work

name attribute

tasks, microtasks, and event loop

NameComponent component

scheduling execution –

name field

lifecycle of application

name prop

lint script

name property

lipsum() function

newKeys set

356

INDEX

newNode object

onUnmounted() lifecycle hook

nextTick() function

dealing with asynchronicity and execution

fundamentals behind

context

implementing

hooks asynchronicity

testing components with asynchronous

hooks execution context

onMounted() hook

onUpdated() lifecycle hook

ngAfterViewInit() lifecycle hook

op property

ngOnChanges() lifecycle hook

originalIndexAt() method

ngOnDestroy() lifecycle hook

originalIndex property

ngOnInit() lifecycle hook

#originalIndices property

nodes, types of

none state

P

noop case

noopItem() method

paint flashing

noop operation

ParentComponent

npm install command

parentEl instance

NPM (Node Package Manager)

parentEl variable

creating NPM account

#patch() method ,

logging in to NPM

patch() method

publishing framework

patchAttrs() function

npm publish command

patchChildren() function

npm run build script

patchChildren() subfunction

null values, removing

patchClasses() function

patchComponent() function

O

patchDOM() function

objects, diffing

adding component case to

objectsDiff() function

and changes in rendering mechanism

offset property

offsets –

passing component’s instance to

-o flag

reconciliation algorithm

onBeforeMount() lifecycle hook

updating state and patching DOM

onBeforeUnmount() lifecycle hook

patchElement() function

onBeforeUpdate() lifecycle hook

patches

onclick event handler

patchEvents() function

onclick event listener

patchStyles() function

oninput event

patchText() function

onMounted() callback

plugins array

onMounted() function

prepack script

onMounted() hook , processJobs() function ,

testing components with

process.nextTick() function

onMounted() lifecycle hook

project, setting up

dealing with asynchronicity and execution

advanced topics

context

configuring from scratch

hooks asynchronicity

examples folder

hooks execution context

runtime package –

on object

ESLint

on property

finding name for framework

onUnmounted() function

NPM package manager

onUnmounted() hook , publishing framework to NPM

Rollup

INDEX

357

project, setting up (continued)

reducers property

source code

remove() method

checking out code for each chapter

removeAttribute() method

fixing bugs

remove case

notes on

removeElementNode() function

reporting problems in

removeEventListener() method

using CDN to import framework

removeEventListeners() function

Vitest

removeFragmentNodes() function

project structure

removeItem() method

Promise

removeItemsAfter() method

props object

removeItemsFrom() method

removing key attribute from

remove operation

props property

remove outstanding items

publishing

removeStyle() function

frameworks

removeTextNode() function

framework to NPM

removeTodo() function

publish NPM script

removeTodo() reducer function

pure function

remove-todo command

pwd command

render() function

render() method , Q

renderApp() function –

queueMicrotask() function

renderApp() method

renderer

R

renderInEditMode() function

renderTodoInEditMode() function

React.createElement() function

renderTodoInReadMode() function

reconciliation algorithm

replaceChild() method

changes in rendering

resolve() function

comparing virtual DOM trees

Rollup, installing and configuring

adding new <span> node

rollup command

applying changes

rollup package

finding differences

@rollup/plugin-commonjs

modifying class attribute and text content of

@rollup/plugin-node-resolve

first <p> node

routes

modifying class attribute and text content of

navigating among

second <p> node

navigating between

modifying id and style attributes of parent

runtime package

<div> node

creating

diffing virtual trees

installing and configuring Rollup

diffing arrays

installing Vitest

diffing arrays as sequence of operations

runtime package

mounting DOM

S

element nodes

fragment nodes

scheduler –

insert() function

functions of

text nodes

implementing

three key functions of

scheduling lifecycle hooks execution

reducer functions

simple solution that doesn’t quite work

reducers, refactoring TODOs application

tasks, microtasks, and event loop

reducers object

scheduleUpdate() function

358

INDEX

search event

components as classes

SearchField component

components with state

separation of concerns

updating state and patching DOM

sequence variable

stateless components

serve:examples script

state management

server side of SSR applications

state manager

setAttribute() function

assembling into framework

setAttributes() function ,