Scala’s Class Hierarchy

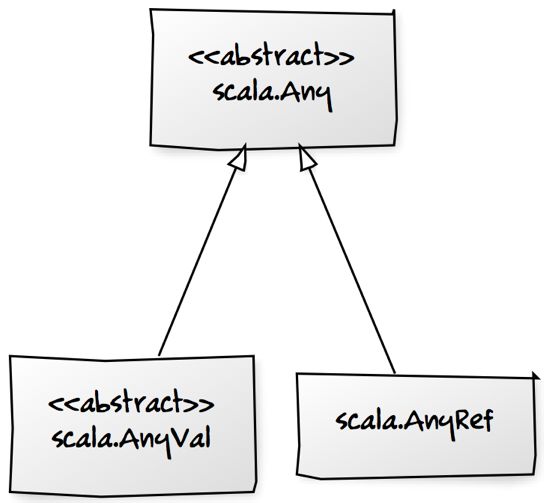

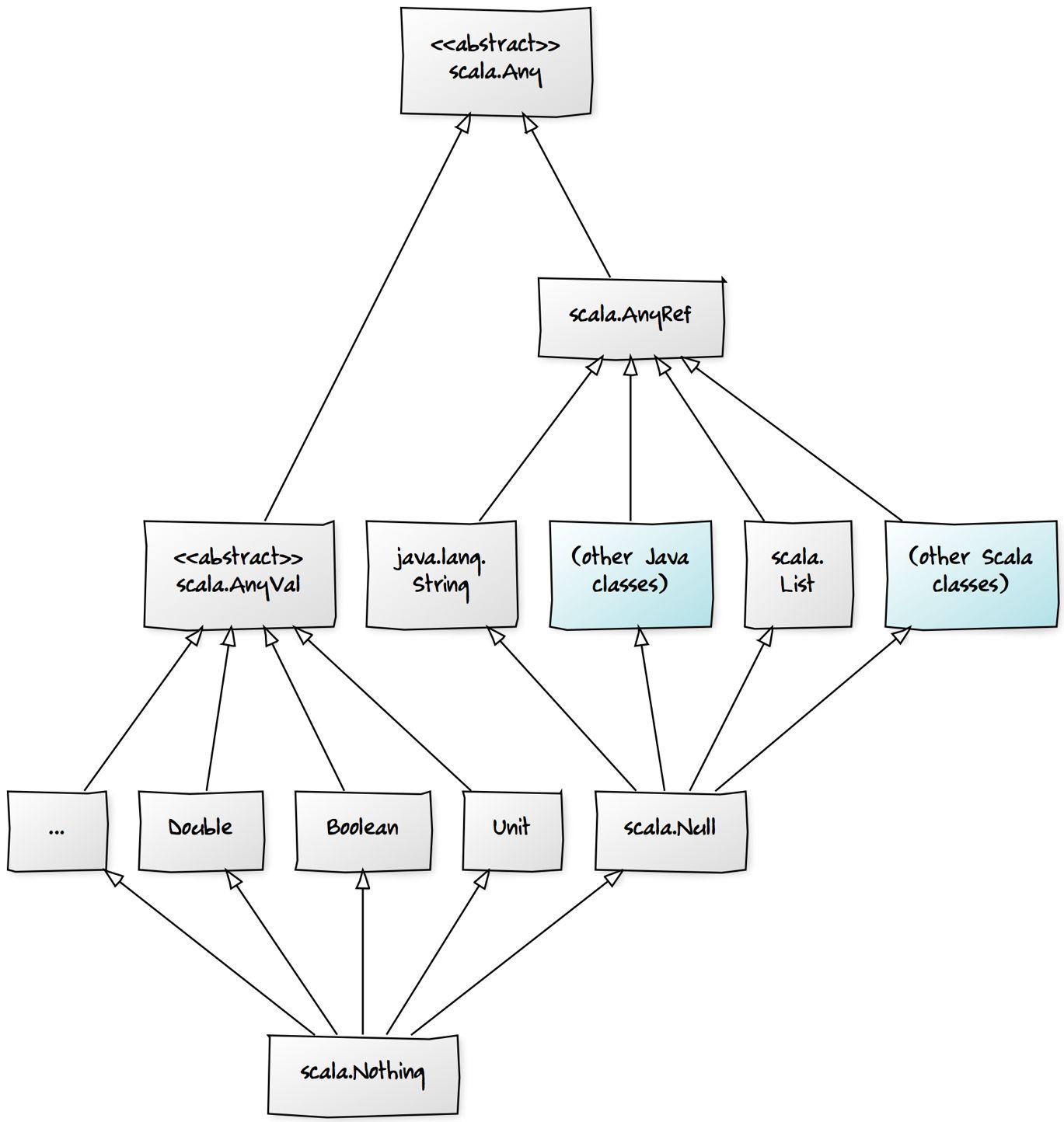

Scala’s class hierarchy starts with the Any class in the scala package. It contains methods like ==, !=, equals, ##, hashCode, and toString.

abstract class Any { final def ==(that: Any): Boolean final def !=(that: Any): Boolean def equals(that: Any): Boolean def ##: Int def hashCode: Int def toString: String // ... } Every class in Scala inherits from the abstract class Any. It has two immediate subclasses, AnyVal and AnyRef.

Fig. 1.1. Every class extends the Any class.

AnyVal

AnyVal is the super-type to all value types, and AnyRef the super-type of all reference types.

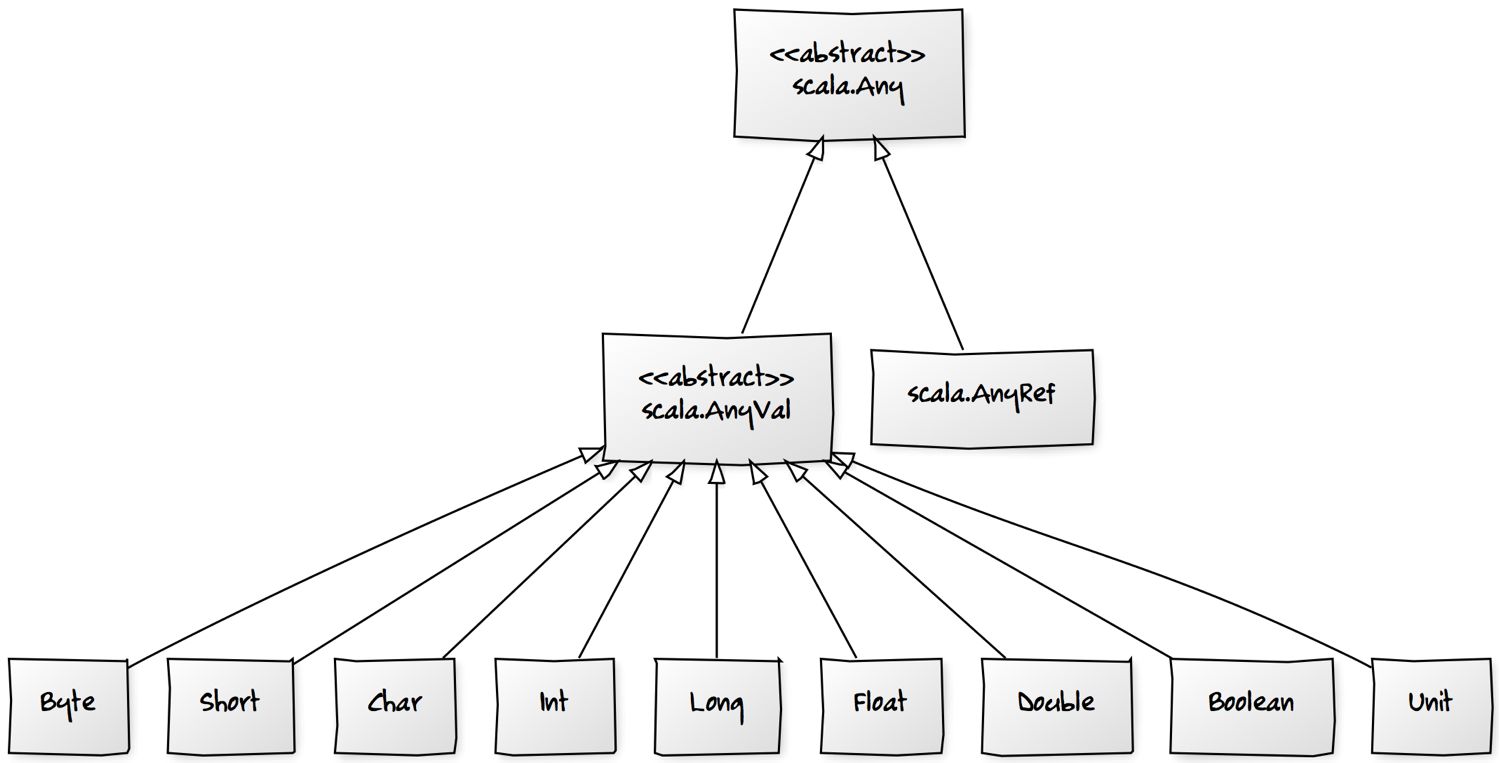

Basic types such as Byte, Int, Char, etc. are known as value types. In Java value types correspond to the primitive types, but in Scala they are objects. Value types are all predefined and can be referred to by literals. They are usually allocated on the stack but are allocated on the heap in Scala.

All other types in Scala are known as reference types. Reference types are objects in memory (the heap), as opposed to pointer types in C-like languages, which are addresses in memory that point to something useful and need to be dereferenced using special syntax (for example, *age = 64 in C). Reference objects are effectively dereferenced automatically.

There are nine value types in Scala:

Fig. 1.2. Scala’s value types.

These classes are fairly straightforward; they mostly wrap an underlying Java type and provide implementations for the == method that are consistent with Java’s equals method.

This means, for example, that you can compare two number objects using == and get a sensible result, even though they may be distinct instances.

So, 42 == 42 in Scala is equivalent to creating two Integer objects in Java and comparing them with the equals method: new Integer(42).equals(new Integer(42)). You’re not comparing object references, like in Java with ==, but natural equality. Remember that 42 in Scala is an instance of Int which in turn delegates to Integer.

Unit

The Unit value type is a special type used in Scala to represent an uninteresting result. It’s similar to Java’s Void object or void keyword when used as a return type. It has only one value, which is written as an empty pair of brackets:

scala> val example: Unit = () example: Unit = () A Java class implementing Callable with a Void object as a return would look like this:

// java public class DoNothing implements Callable<Void> { @Override public Void call() throws Exception { return null; } } It is identical to this Scala class returning Unit:

// scala class DoNothing extends Callable[Unit] { def call: Unit = () } Remember that the last line of a Scala method is the return value, and () represents the one and only value of Unit.

AnyRef

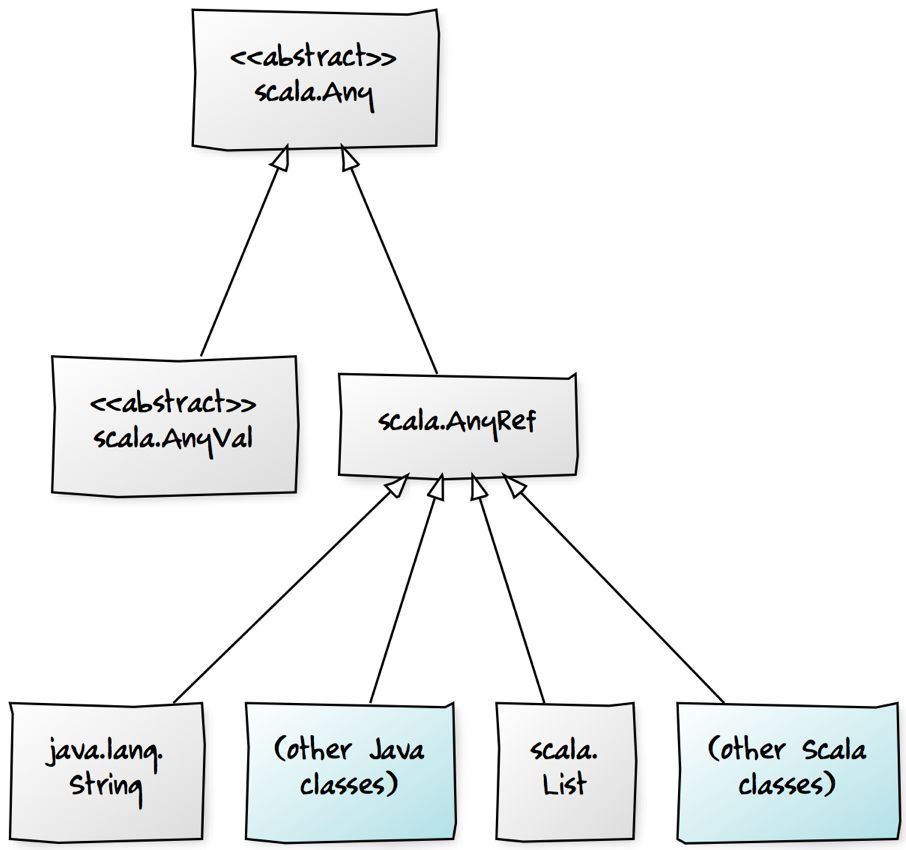

AnyRef is an actually an alias for Java’s java.lang.Object class. The two are interchangeable. It supplies default implementations for toString, equals and hashcode for all reference types.

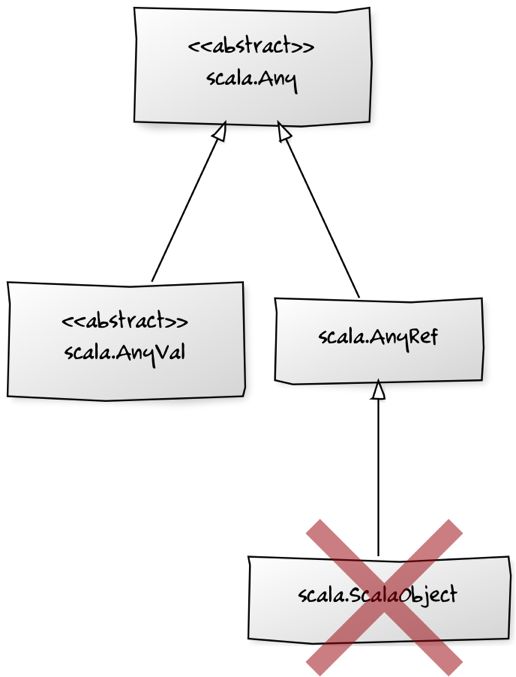

There used to be a subclass of AnyRef called ScalaObject that all Scala reference types extended. However, it was only there for optimisation purposes and has been removed in Scala 2.11. (I mention it as a lot of documentation still refers to it.)

Fig. 1.3. Scala Any. The ScalaObject class no longer exists.

The Java String class and other Java classes used from Scala all extend AnyRef. (Remember it’s a synonym for java.lang.Object.) Any Scala-specific classes, like Scala’s implementation of a list, scala.List, also extend AnyRef.

Fig. 1.4. Scala’s reference types.

For reference types like these, == will delegate to the equals method like before. For pre-existing classes like String, equals is already overridden to provide a natural notion of equality. For your own classes, you can override the equals just as you would in Java, but still be able to use == in code.

For example, you can compare two strings using == in Scala and it would behave just as it would in Java if you used the equals method:

new String("A") == new String("A") // true in scala, false in java new String("B").equals(new String("B")) // true in scala and java If, however, you want to revert back to Java’s semantics for == and perform reference equality in Scala, you can call the eq method defined in AnyRef:

new String("A") eq new String("A") // false in scala new String("B") == new String("B") // false in java Bottom Types

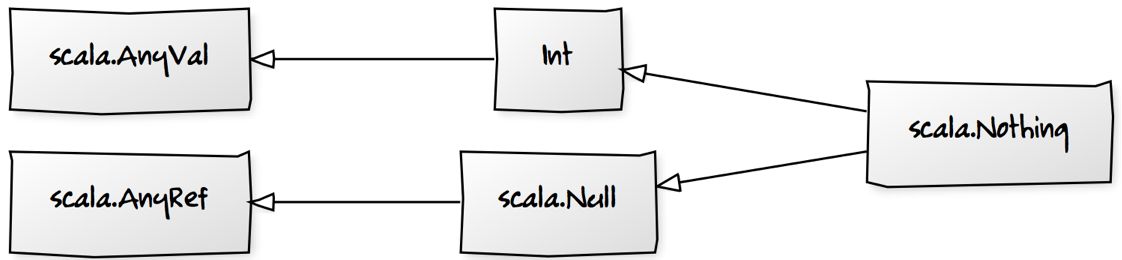

A new notion to many Java developers will be the idea that a class hierarchy can have common bottom types. These are types that are subtypes of all types. Scala’s types Null and Nothing are both bottom types.

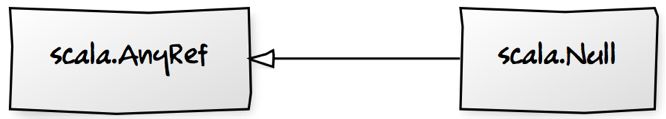

All reference types in Scala are super-types of Null. Null is also an AnyRef object; it’s a subclass of every reference type.

Fig. 1.5. The Null extends AnyRef.

Both value and reference types are super-types of Nothing. It’s at the bottom of the class hierarchy and is a subtype of all types.

Fig. 1.6. Nothing extends Null.

The entire hierarchy is shown in the diagram below. I’ve left off scala.Any to save space. Notice that Null extends all reference types and that Nothing extends all types.

Fig. 1.7. Full hierarchy with the bottom types Null and Nothing.