Exercises

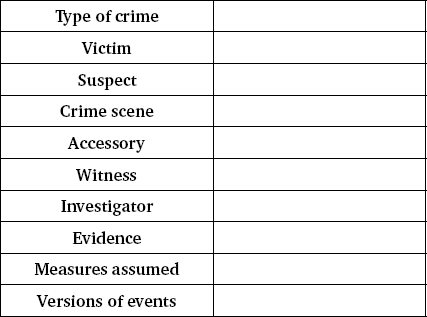

I. Retell the facts we know about the crime committed. Complete the table below.

II. Note the use of the tenses in the phrase given below. What tenses are employed and why? Reconstruct the sequence of events.

Now, by the merest chance, his wife received a telegram the same Monday, very shortly after his departure, that a small parcel of considerable value which she had been expecting was waiting for her at the offices of the Aberdeen Shipping Company.

1. Mrs. St. Clair receives a telegram;

2. Mr. St. Clair leaves his house;

3. Mrs. St. Clair is expecting a parcel;

4. The parcel is delivered to the offices of the Aberdeen Shipping Company.

III. Translate the following sentences from Russian into English, using the correct tenses.

1. Доктор Ватсон поехал в притон, потому что к нему пришла жена Айзы Уитни и попросила вытащить оттуда мужа, который находился там уже двое суток.

2. Когда Ватсон приехал в притон и в темноте искал Айзу Уитни, он обнаружил там Холмса, который переоделся стариком.

3. Ватсон отправил Айзу Уитни домой и дождался Холмса, который попросил присоединиться к нему по пути из притона, где он выслеживал преступника.

4. Как и предложил Холмс, Ватсон отправил жене записку о том, что встретил друга и помогает ему вести расследование.

IV. Study the expressions in italics. What images have caused the existence of such meanings?

Between a slop-shop and a gin-shop, there were steep steps leading down to a black gap like the mouth of a cave.

At the foot of the stairs, however, she met this Lascar of whom I have spoken, who pushed her back and, with a help of a guard, let her out into the street.

V. Translate the expression given below. Do some of them correspond with their Russian equivalents?

Mouth of a bottle; mouth of a river; mouth of a volcano; foot of a page; foot of a table; foot of a mountain.

VII. What other figurative meanings of different parts of the body do you know?

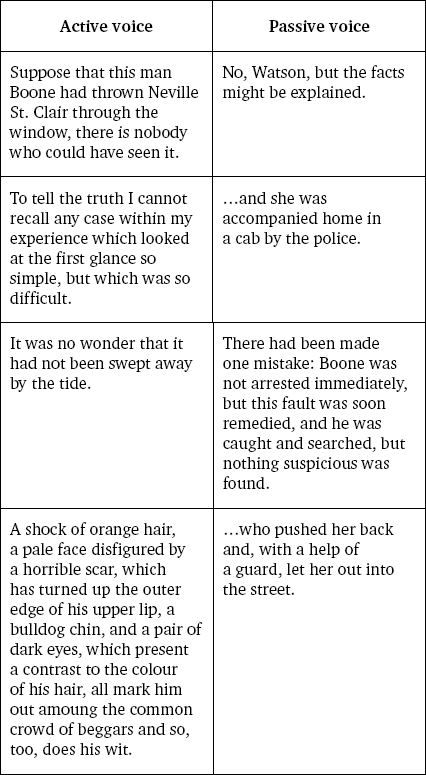

VIII. Look at the table below. Note the use of the Active and Passive voices. Do all the sentences stand in the right place? Find out in what sort of sentences each voice is likely to be used.

IX. Rewrite the sentences into the opposite voice.

III

While Sherlock Holmes had been telling the details of event, we had been driving through the outskirts of the great town until the last houses had been left behind, and we rode across the countryside. Just as he finished, however, we drove through two villages, where there were still a few lights in the windows.

“We are on the outskirts of Lee,” said my friend. “We have visited three English counties in our short drive, starting in Middlesex, passing over an angle of Surrey, and ending in Kent. See that light among the trees? That is The Cedars, and beside that lamp sits a woman and I’m sure her anxious ears have already heard the clink of our horse’s feet.”

“But why are you not conducting the case from Baker Street?” I asked.

“Because there are many inquiries which must be made out here. Mrs. St. Clair has most kindly put two rooms at my disposal, and you may stay and be sure that she will have nothing but a welcome for my friend and colleague. I don’t want to meet her, Watson, when I have no news of her husband. Here we are.”

We had stopped in front of a large villa which was surrounded by its own garden. A servant had taken the horses away, and I followed Holmes up the small path which led to the house. As we came closer, the door opened, and a little blonde woman stood in the opening, dressed in some sort of light mousseline de soie. She stood with her figure outlined against the light, one hand upon the door, one half-raised in her impatience, with bright eyes and her mouth open she was a standing question.

“Well?” she cried, “well?” And then, seeing that there were two of us, she gave a cry of hope. But Holmes shook his head and shrugged his shoulders.

“No good news?”

“None.”

“No bad?”

“No.”

“Thank God for that. But come in. You must be tired, for you have had a long day.”

“This is my friend, Dr. Watson. He has helped me a lot in several of my cases, and a lucky chance has made it possible for me to bring him here and involve him in this investigation.”

“I am glad to see you,” said she, shaking my hand warmly. “Sorry for the inconvenience you may feel here, the trouble has come so suddenly upon us.”

“My dear madam,” said I, “I am an old soldier. Besides I can very well see that no apology is needed. If I can help, either you or my friend here, I will be indeed happy.”

“Now, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said the lady as we entered a well-lit dining-room, upon the table of which was a cold supper, “I should very much like to ask you one or two plain questions. Please give me plain answers to them.”

“Certainly, madam.”

“Do not worry about my feelings. I am not hysterical. I simply wish to hear your real, real opinion.”

“About what?”

“In your heart of hearts, do you think that Neville is alive?”

Sherlock Holmes seemed to be confused by the question. “Frankly, now!” she repeated.

“Frankly, then, madam, I do not.”

“You think that he is dead?”

“I do.”

“Murdered?”

“I don’t say that. Perhaps.”

“And on what day did he meet his death?”

“On Monday.”

“Then perhaps, Mr. Holmes, you will be good enough to explain how it is that I have received a letter from him today.”

Sherlock Holmes jumped out of his chair.

“What!” he cried.

“Yes, today.” She stood smiling, holding up a little sheet of paper.

“May I see it?”

“Certainly.”

He took it from her impatiently, laid it on the table and examined it carefully in the lamplight. I had left my chair and was looking at it over his shoulder. The envelope was very cheap and was stamped with the Gravesend postmark and with the date of that very day, or rather of the day before, because it was after midnight.

“Surely this is not your husband’s writing, madam,” said Holmes.

“No, but the enclosure is.”

“I can also see that the man who addressed the envelope had to go and ask about the address.”

“How can you tell that?”

“The name, you see, is in perfectly black ink, which has dried itself. The rest is of the gray colour, which shows that blotting-paper has been used. If it had been written at once, and then blotted, none would be of a deep black colour. This man has written the name, and there has then been a pause before he wrote the address, which can only mean that he didn’t know it. It is, of course, a detail, but there is nothing so important as details. Let us now see the letter. Ha! there has been some object here!”

“Yes, there was a ring. His signet-ring.”

“And you are sure that this is your husband’s writing?”

“One of them.”

“One?”

“His writing when he wrote in a hurry. It is very unlike his usual writing, but I know it well.”

“ ‘Dearest do not be frightened. All will come well. There is a huge mistake which it may take some little time to put right. Wait in patience. – NEVILLE.’ Written in pencil upon the leaf of a book, no water-mark. Hum! Posted today in Gravesend by a man with a dirty finger. Ha! And the envelope has been sealed by a person who had been chewing tobacco. And are you sure that it is your husband’s hand, madam?”

“Absolutely. Neville wrote those words.”

“And they were posted today at Gravesend. Well, Mrs. St. Clair, the clouds lighten, though I can’t say that the danger is over.”

“But he must be alive, Mr. Holmes.”

“Unless this is a clever forgery to put us on the wrong scent. The ring, after all, proves nothing. It may have been taken from him.”

“No, no; it is, it is his own writing!”

“Very well. It may, however, have been written on Monday and only posted today.”

“That is possible.”

“If so, something may have happened between.”

“Oh, you must not discourage me, Mr. Holmes. I know that all is well with him. There is such strong sympathy between us that I should know if evil came upon him. On the last day that I saw him he cut himself in the bedroom. I was in the dining-room, but I rushed upstairs immediately, because I was sure that something had happened. Do you think that I would react on such a trifle, but wouldn’t feel his death?”

“I have seen too much and I know that the impression of a woman may be more valuable than the logical conclusion. And in this letter you certainly have a very strong piece of evidence to prove your view. But if your husband is alive and able to write letters, why would he be away from you?”

“I cannot imagine. It is unexplainable.”

“And on Monday he said nothing before leaving you?”

“No.”

“And you were surprised to see him in Swandam Lane?”

“Very much so.”

“Was the window open?”

“Yes.”

“Then, maybe, he called you?”

“Maybe.”

“He only, as I understand, gave an inarticulate cry?”

“Yes.”

“A call for help, you thought?”

“Yes. He waved his hands.”

“But it might have been a cry of surprise. He didn’t expect to see you, and it might have caused him to throw up his hands?”

“It is possible.”

“And you thought somebody pulled him back?”

“He disappeared so suddenly.”

“He might have jumped back. You did not see anyone else in the room?”

“No, but this horrible man confessed he had been there, and the Lascar was at the foot of the stairs.”

“Quite so. Your husband, as far as you could see, had his ordinary clothes on?”

“But without his collar or tie. I certainly saw it.”

“Had he ever spoken of Swandam Lane?”

“Never.”

“Had he ever showed any signs of having taken opium?”

“Never.”

“Thank you, Mrs. St. Clair. Those are the main points about which I wanted to be absolutely clear. We shall now have a little supper and then go to sleep, because we may have a very busy day tomorrow.”

A large and comfortable double-bedded room was prepared for us, and I went quickly to bed, because I was tired after my night of adventure. Sherlock Holmes was a man, however, who, when he had an unsolved problem upon his mind, would work for days, and even for a week, without rest, turning it over, looking at it from every point of view until he had either solved it or understood that he had not had enough facts. Soon I realized that he was now preparing for an all-night sitting. He took off his coat and waistcoat, put on a large blue dressing-gown, and then walked about the room taking pillows from his bed and cushions from the sofa and armchairs. With these he constructed a sort of Eastern divan, upon which he sat cross-legged, with some tobacco and a box of matches laid out in front of him. In the light of the lamp I saw him sitting there, an old pipe between his lips, his eyes fixed indifferently upon the corner of the ceiling, the blue smoke curling up from him, silent, motionless, with the light shining upon his aquiline features.