Exercises

1. Answer the questions:

1. What client called on Sherlock Holmes one day? What did he look like?

2. What did Sherlock Holmes tell Dr. Watson about Mr. Wilson’s case?

3. What did Sherlock Holmes guess about Mr. Wilson? What details helped him? Was Mr. Wilson impressed? Why (not)?

4. What did Mr. Wilson tell Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson about his business and household?

5. What did you learn about Mr. Wilson’s assistant?

6. How did Mr. Wilson learn about a vacancy on the Red-headed League?

7. Was Mr. Wilson enthusiastic about the vacancy? Why (not)?

8. Why did Mr. Wilson go to Fleet Street in the end?

9. Why did he take his assistant with him?

10. What did Mr. Wilson see in Fleet Street and in the office of the Red-headed League?

11. Whom did Mr. Wilson meet in the office? Did Mr. Ross employ him at once?

12. What was the work like?

2. Think and say if these statements are right or wrong. Correct the wrong ones, give your reasons.

1. Vincent Spaulding agreed to work for Mr. Wilson for half the wages to learn the business.

2. An American millionaire Ezekiah Hopkins left his enormous fortune to help and propagate red-headed men in London.

3. Mr. Wilson was sure that the whole affair of the Red-Headed League was a fraud and wanted Sherlock Holmes to explain to him what it was all about.

3. Find the following phrases in the text and reproduce situations from the text with them. Give Russian equivalents.

1. as far as (I have heard / I know)

2. used to do smth / didn’t use to do smth

3. to be going on

4. it’s no use (smb’s) doing smth

5. to find oneself in some place

6. to shout at the top of one’s voice

7. to see to smth / to see to it that

8. to turn up

4. Paraphrase the underlined parts of the sentences so as to use the phrases above.

1. As the teacher came into the classroom where all the children were fighting she asked: “What is happening here?”

2. Eliza’s neighbour promised her to take care of her cat while she was away.

3. If such a job comes your way, don’t hesitate to take it.

4. In the past there were high trees opposite my house but there aren’t any left.

5. It’s useless arguing with her. She just won’t listen.

6. I suddenly realized that I had arrived back at the hotel without knowing how I came there.

7. It was so noisy in the night club that we had to shout as loudly as we could to be heard.

5. Complete the sentences with the phrases above in the correct form (one gap for a phrase).

1. When the boys disappeared Aunt Polly was very anxious and made a lot of people look for them. But then the wise heads decided that the boys had gone off on the raft and would soon… at the next town down the river.

2. There’s something that makes her anxious and unhappy. I wonder what it is. – How do you know? – She often sits in front of the fire thinking of something and paying no attention to what… around her.

3… I know, he… be a good sportsman in his younger days, but I’m not sure if he plays any sports now.

4. I’m surprised to see you smoking, you didn’t… smoke.

5… complaining, they won’t do anything about it.

6. After the accident Ben… in hospital.

7. I looked out of the window to see two small boys… I thought they were quarrelling but they were just playing.

II

“Well, I thought over the matter all day, and by evening I was in low spirits again; for now I was sure that the whole affair must be some great fraud. It seemed very strange that anyone could make such a will, or that they would pay such a sum for doing anything so simple as copying out the Encyclopaedia Britannica. However, in the morning I decided to have a look at it after all, so I bought a bottle of ink, and with a pen and seven sheets of paper, I started off for Fleet Street.

“Well, to my surprise and delight, everything was all right. The table was ready for me, and Mr. Duncan Ross was there to see that I started work. He told me to start with the letter A, and then he left me; but he came from time to time to see that all was right with me. At two o’clock he said good-bye to me, and locked the door of the office after me.

“This went on day after day, Mr. Holmes, and on Saturday the manager came in and paid four golden sovereigns for my week’s work. It was the same next week, and the same the week after. Every morning I was there at ten, and every afternoon I left at two. Usually Mr. Duncan Ross came in the morning, but after a time, he stopped coming in at all. Still, of course, I never left the room for a moment, for I was not sure when he might come, and the position was so good, and suited me so well, that I did not want to risk losing it.

“Eight weeks passed like this, and I had written almost all the letter A, and hoped that I soon might get on to the B.

“This morning I went to my work as usual at ten o’clock, but the door was locked, with a little note on it. Here it is, and you can read for yourself.”

He showed us a piece of paper. It read:

THE RED-HEADED LEAGUE IS DISSOLVED.

October 9, 1890.

Sherlock Holmes and I read this short note and looked at the sad face behind it, and the comical side of the affair was so obvious that we both burst out laughing.

“I cannot see that there is anything very funny,” cried our client. “If you can do nothing better than laugh at me, I can go to another detective.”

“No, no,” cried Holmes. “I really wouldn’t miss your case for the world. It is most unusual. But there is something a little funny about it. What did you do when you found the note on the door?”

“I was astonished, sir. I did not know what to do. Then I called at the offices round, but nobody knew anything about it. I went to the landlord, who is living on the ground-floor, and I asked him if he could tell me what had become of the Red-headed League. He said that he had never heard of it. Then I asked him who Mr. Duncan Ross was. He answered that the name was new to him.

“‘Well,’ said I, ‘the gentleman at No. 4.’

“‘What, the red-headed man?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘Oh,’ said he, ‘his name was William Morris. He was a solicitor and was using my room until his new office was ready. He moved out yesterday.’

“‘Where can I find him?’

“‘Oh, at his new office. He told me the address. Yes, 17 King Edward Street.’

“I started off, Mr. Holmes, but when I got to that address it was a manufactory, and no one in it had ever heard of either Mr. William Morris or Mr. Duncan Ross.”

“And what did you do then?” asked Holmes.

“I went home to Saxe-Coburg Square, and I took the advice of my assistant. But he could not help me. He could only say that if I waited I might get a letter. But that was not good enough, Mr. Holmes. I did not wish to lose such a place without a struggle, so, as I had heard that you gave good advice to poor people, I came to you.”

“And you did very well,” said Holmes. “Your case is remarkable, and I shall be happy to look into it. The affair may be very serious.”

“Of course serious!” said Mr. Jabez Wilson. “I have lost four pounds a week.”

“As far as you are personally concerned,” remarked Holmes, “I do not see that you have anything against this extraordinary league. On the contrary, you are, as I understand, richer by about 30 pounds, to say nothing of the knowledge which you have got on every subject which comes under the letter A. You have lost nothing.”

“No, sir. But I want to find out about them, and who they are, and why they played this trick – if it was a trick – on me. It was a pretty expensive joke for them, for it cost them thirty-two pounds.”

“We shall try to clear up these points for you. And, first, one or two questions, Mr. Wilson. This assistant of yours who first brought you the advertisement – how long had he been with you?”

“About a month then.”

“How did he come?”

“In answer to an advertisement.”

“Was he the only who answered the advertisement?”

“No, I had a dozen.”

“Why did you choose him?”

“Because he was cheap.”

“At half wages.”

“Yes.”

“What is he like, this Vincent Spaulding?”

“Small, very quick, no hair on his face, about thirty. He has a white scar on his forehead.”

Holmes sat up in his chair very much excited. “I thought as much,” said he. “Are his ears pierced for earrings?”

“Yes, sir. He told me he had done it when he was a boy.”

“He is still with you?”

“Oh, yes, sir; I have only just left him.”

“And has he worked well in your absence?”

“Yes, sir. There’s never very much to do in the morning.”

“That will do, Mr. Wilson. I shall be happy to give you an opinion on the matter in a day or two. Today is Saturday, and I hope that by Monday we may come to a conclusion.”

“Well, Watson,” said Holmes when our visitor had left us, “what do you make of it all?”

“I make nothing of it,” I answered. “It is a very mysterious business.”

“As a rule,” said Holmes, “the more unusual a thing is the less mysterious it is in the end. But I must hurry up.”

“What are you going to do, then?” I asked.

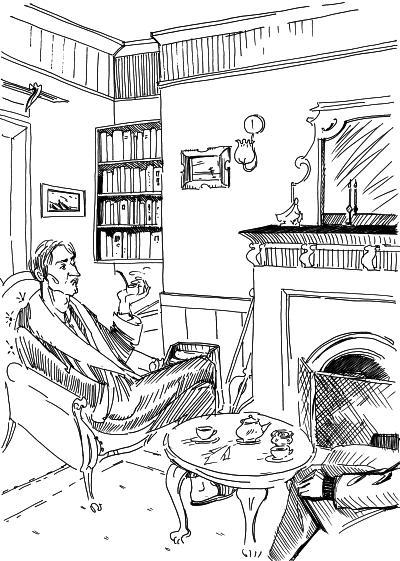

“To smoke,” he answered. “It is a three pipe problem, and I ask you not to speak to me for fifty minutes.” He sat in his chair, with his eyes closed. I had come to the conclusion that he had fallen asleep, when he suddenly sprang out of his chair like a man who had made up his mind and put his pipe down on the table.

“What do you think, Watson? Could you come with me for a few hours?” he said.

“I have nothing to do today. My practice is never very busy.”

We travelled by the Underground first; and then a short walk took us to Saxe-Coburg Square, the scene of the unusual story which we had listened to in the morning. It was a little, shabby place, where two-storeyed houses looked out into a small garden. A brown board with “JABEZ WILSON” in white letters on a corner house showed us the place where our red-headed client carried on his business. Sherlock Holmes stopped in front of it and looked it all over. Then he walked slowly up the street, and then down again to the corner, still looking at the houses. Finally he returned to the pawnbroker’s, struck on the ground with his stick two or three times, went up to the door and knocked. It was opened by a young fellow, who asked him to come in.

“Thank you,” said Holmes, “I only wished to ask you how I could go from here to the Strand.”

“The first turning to the left,” answered the assistant, closing the door.

“Smart fellow,” remarked Holmes as we walked away. “I think, he is the fourth smartest man in London. I have known something of him before.”

“Evidently,” said I, “Mr. Wilson’s assistant is involved in this mystery of the Red-headed League. I am sure that you asked your way only to see him.”

“Not him.”

“What then?”

“The knees of his trousers.”

“And what did you see?”

“What I expected to see.”

“Why did you strike the ground?”

“My dear doctor, this is a time for action, not for talk. We are spies in an enemy’s country. We know something of Saxe-Coburg Square. Let us now see some other places.”

The road in which we found ourselves as we turned round the corner from Saxe-Coburg Square was a great contrast to it. It was one of the main arteries with busy traffic. It was difficult to realize as we looked at the line of fine shops and business offices that they were really on the other side of the quiet square which we had just left.

“Let me see,” said Holmes, standing at the corner and glancing along the street, “I should like to remember the order of the houses here. There is Mortimer’s, the tobacconist, the little newspaper shop, the Coburg branch of the City and Suburban Bank, the Vegetarian Restaurant. And now, Doctor, we’ve done our work.

“Do you want to go home?”

“Yes.”

“And I have some business to do which will take some hours. This business at Coburg Square is serious.”

“Why serious?”

“A crime is being prepared. I believe that we shall be in time to stop it. I shall want your help tonight.”

“At what time?”

“At ten. There may be some danger, so put your army revolver in your pocket.” And he disappeared in the crowd.

I must say I always felt stupid when I was with Sherlock Holmes. I had heard what he had heard, I had seen what he had seen, and yet from his words it was evident that he saw clearly not only what had happened but what was going to happen, while to me the whole business was still a mystery. As I drove home to my house in Kensington I thought over it. Where were we going, and what were we to do? I had the hint from Holmes that this pawnbroker’s assistant was a criminal. But I could not think what he was up to and then decided that the night would bring an explanation.