W

waste n ненужная трата, потеря

whimsical a причудливый

whine v ныть, хныкать

whistle n свист

windfall n опавшие плоды; неожиданная удача

wind-swept продуваемый ветром

woodcock n вальдшнеп

worse for wear видавший виды

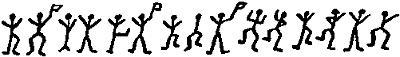

Пляшущие человечки

The Adventure of the Dancing Men

Адаптация текста, упражнения, комментарии и словарь Д. В. Положенцевой

I

Holmes had been sitting for some hours in silence over a chemical vessel in which he was brewing something very unpleasant. His head was sunk upon his breast, and he looked from my point of view like a strange, skinny bird.

“So, Watson,” he said, suddenly, “you are not going to invest money in South African securities?”

I was very much surprised. Although I was accustomed to Holmes’s curious abilities, this sudden intrusion into my thoughts was rather incomprehensible.

“How on earth do you know that?” I asked in amazement.

He turned his chair, holding a steaming test-tube in his hand. I saw a gleam of amusement in his deep-set eyes.

“Now, Watson, confess, you are confused,” he said.

“I am.”

“I should make you write this on the piece of paper and leave your signature.”

“Why?”

“Because in five minutes you will say that it is all very simple and obvious.”

“I am sure that I shall say nothing of the kind.”

“You see, my dear Watson”– he put aside his test-tube and began to lecture like a professor addressing his class —“it is not really difficult to construct a series of conclusions, each dependent on the previous one. And if you simply take away all the central elements and show your audience only the first and the last ones, it will produce an amazing effect. Now, when I noticed the groove between your left forefinger and thumb, it was not really difficult to understand that you do not want to invest your small capital in the goldfields.”

“I see no connection.”

“Well, I believe you, but I can quickly show you a close connection. Here are the missing links of the very simple chain: 1. You had chalk between your left finger and thumb when you returned from the club last night. 2. You put chalk there for the cue when you play billiards. 3. You play billiards only with Thurston. 4. You told me four weeks ago that Thurston wanted to buy some South African securities and share them with you. 5. Your cheque-book is locked in my table, and you have not asked for the key. 6. You are not going to invest your money in anything.”

“So simple!” I cried.

“Yes, it is!” he said. “Every problem becomes very simple when it is explained to you. But here you are, this one is not explained yet. Let’s see what you can say, my friend Watson.” He gave me a sheet of paper and turned to his chemical analysis.

I looked with amazement at the strange symbols on the paper.

“Well, Holmes, it is a child’s drawing,” I said.

“Oh, that’s your idea!”

‘What else should it be?”

“That is what Mr. Hilton Cubitt from Norfolk wants to know. He sent us this little puzzle and every minute we expect him. Oh, there’s a ring at the bell, Watson. I am not very much surprised if it is our guest.”

We heard heavy steps on the stairs, and a second later a tall gentleman entered. He had clear eyes and florid cheeks which told us that he led his life far from the fogs of Baker Street. He seemed to bring strong, fresh air with him as he entered. He shook hands with each of us and was going to sit down when he noticed the paper with the curious symbols, which I had just examined and left on the table.

“Well, Mr. Holmes, what do you think about it?” he cried. “I heard that you liked strange mysteries, and this one is the strangest, I think! I sent the paper ahead so that you have time to study it before I came.”

“Yes, it is very curious,” said Holmes. “At first sight one can think that it’s a child’s drawing. It consists of funny little dancing figures. Why do you pay so much attention on such an object?”

“I don’t, Mr. Holmes. But my wife does. It is frightening her to death. She says nothing, but I can see fear in her eyes. That’s why I want to find everything out.”

Holmes took the paper and turned to the sunlight. It was a page from a note-book. The symbols were done in pencil, and were in this order —

Holmes examined it for some time, and then folded it carefully and put it in his pocket-book.

“This promises to be a very interesting and unusual case,” he said. “You gave me a few details in your letter, Mr. Hilton Cubitt, but I would be very grateful if you tell the story again, for my friend, Dr. Watson.”

“I’m not good at telling stories,” said our visitor. He was rather nervous. “You’ll just ask questions if something is unclear. I’ll begin from my marriage last year; but I want to say first of all, that although I’m not a rich man, my family has been at Ridling Thorpe for five centuries and it is well-known in the County of Norfolk. Last year I came to London and stopped at a boarding-house in Russell Square. There was an American young lady there… Elsie Patrick. Somehow we became friends, until I fell in love with her as a man could be. We got quietly married and returned to Norfolk as a couple. You’ll think it is very mad, Mr. Holmes, that a man of a good old family could marry a woman like this, knowing nothing of her past or of her family. But if you saw her and knew her it would help you to understand.”

“Elsie was very straight. She gave me an opportunity to think it over and cancel the wedding if I wanted to do so. ‘I have had something very unpleasant in my life,’ she said; ‘I want to forget all about it, because it is very painful to me. If you marry me, Hilton, you will marry a woman who did nothing wrong. But you will have to believe me and to allow me to be silent about my past to the time when I became yours. If these conditions are too difficult, then leave me and go back to Norfolk. And I’ll lead my lonely life here in which you found me.’ It was the day before our wedding. I told her that I agreed with her conditions, and I keep my word.”

“Well, we have been happily married already for a year. But about a month ago, at the end of June, for the first time I saw some signs of trouble. One day my wife received a letter from America. I saw the American stamp. She turned white, read the letter and threw it into the fire. She didn’t tell me anything, and I didn’t say a word, because a promise is a promise; but from that moment she has always been uneasy. There is always a look of fear on her face… a look as if she is expecting something. If only she trusted me – she would see that I was her best friend. But if she doesn’t speak, I can say nothing. She is an honest woman, Mr. Holmes, and whatever trouble have been in her past life it is not her fault. I am only a simple Norfolk squire, but there is no one in England who values his family honour more than I do. She knows it well, and she knew it well before she married me. She will never leave any stain on it… I am sure.”

“Well, now I come to the strange part of my story. About a week ago… it was the Tuesday of last week… I found on one of the windowsills some little dancing figures, like these on the paper. They were written with chalk. I thought that it was the stable-boy who had drawn them, but he swore he knew nothing about it. Anyway, they had appeared there during the night. I had them washed out and mentioned the matter to my wife afterwards. To my surprise she took it very seriously, and asked me if any more figures appeared to let her see them. And yesterday morning I found this paper on the sun-dial in the garden. I showed it to Elsie, and she fainted. Since then her eyes have been full of terror. That’s why I wrote and sent the paper to you, Mr. Holmes. I think I couldn’t take it to the police, because they would have laughed at me, but you will tell me what to do. I am not a rich man; but if there is any danger threatening my wife I would spend my last money to save her.”

He was a kind person, this man of the old English soil, simple, straight, and gentle, with his great, earnest blue eyes and broad face. His love for his wife was true and his trust in her was touching. Holmes had listened to his story with the greatest attention, and now he sat for some time in silence.

“Don’t you think, Mr. Cubitt,” he said at last, “that it will be better to talk to your wife directly and to ask her to share her secret with you?”

Hilton Cubitt shook his big head.

“A promise is a promise, Mr. Holmes. If Elsie wished to tell me she would. If not, I can’t make her to do so. But I have the right to find out everything myself… and I will.”

“Then I will help you with all my heart. So, first of all, have you heard of any strangers in your neighbourhood?”

“No.”

“I suppose that it is a very quiet place. You would notice any new face, wouldn’t you?”

“In my neighbourhood, yes. But we have several small villages not very far away. And the farmers rent houses.”

“These symbols have evidently a meaning. If it is random, it may be impossible for us to solve it. If, on the other hand, it is systematic, I am sure that we shall read this riddle. But this one is so short that I can do nothing. And the facts which you have told us are not enough that we have a basis for investigation. I would suggest that you return to Norfolk, that you watch everything closely, and that you take an exact copy of any dancing men which may appear. It is a pity that we have not a copy of those which were done in chalk on the windowsill. Make inquiries about any strangers in the neighbourhood. When you have collected some evidence, come to me again. That is the best advice which I can give you, Mr. Hilton Cubitt. If you need my help, I shall be always ready to come and see you in your Norfolk house.”