Rumpelstiltskin

Once there was a miller who was poor, but who had a beautiful daughter. Now it happened that he had to go and speak to the king, and in order to make himself appear important he said to him, ‘I have a daughter who can spin straw into gold.’

The king said to the miller, ‘That is an art which pleases me well, if your daughter is as clever as you say, bring her tomorrow to my palace, and I will put her to the test.’

And when the girl was brought to him he took her into a room which was quite full of straw, gave her a spinning-wheel and a reel, and said, ‘Now set to work, and if by tomorrow morning early you have not spun this straw into gold during the night, you must die.’

Thereupon he himself locked up the room, and left her in it alone. So there sat the poor miller’s daughter, and could not tell what to do, she had no idea how straw could be spun into gold, and she grew more and more frightened, until at last she began to cry.

But all at once the door opened, and in came a little man, and said, ‘Good evening, mistress miller, why are you crying?’

‘Oh,’ answered the girl, ‘I have to spin straw into gold, and I do not know how to do it.’

‘What will you give me,’ said the manikin, ‘if I do it for you?’

‘My necklace,’ said the girl.

The little man took the necklace, seated himself in front of the wheel, and whirr, whirr, whirr, three turns, and the reel was full, then he put another on, and whirr, whirr, whirr, three times round, and the second was full too. And so it went on until the morning, when all the straw was spun, and all the reels were full of gold.

By daybreak the king was already there, and when he saw the gold he was astonished and delighted, but his heart became only more greedy. He had the miller’s daughter taken into another room full of straw, which was much larger, and commanded her to spin that also in one night if she valued her life. The girl knew not how to help herself, and was crying, when the door opened again, and the little man appeared, and said, ‘What will you give me if I spin that straw into gold for you?’

‘The ring on my finger,’ answered the girl.

The little man took the ring, again began to turn the wheel, and by morning had spun all the straw into glittering gold.

The king rejoiced beyond measure at the sight of it, but still he had not enough gold, and he had the miller’s daughter taken into a still larger room full of straw, and said, ‘You must spin this, too, in the course of this night, but if you succeed, you shall be my wife.’

Even if she be a miller’s daughter, thought he, I could not find a richer wife in the whole world.

When the girl was alone the manikin came again for the third time, and said, ‘What will you give me if I spin the straw for you this time also?’

‘I have nothing left that I could give,’ answered the girl.

‘Then promise me, if you should become queen, to give me your first child.’

Who knows whether that will ever happen, thought the miller’s daughter, and, not knowing how else to help herself in this strait, she promised the manikin what he wanted, and for that he once more spun the straw into gold.

And when the king came in the morning, and found all as he had wished, he took her in marriage, and the pretty miller’s daughter became a queen.

A year after, she born a beautiful child, and she never gave a thought to the manikin. But suddenly he came into her room, and said, ‘Now give me what you promised.’

The queen was horror-struck, and offered the manikin all the riches of the kingdom if he would leave her the child. But the manikin said, ‘No, something alive is dearer to me than all the treasures in the world.’

Then the queen began to cry, so that the manikin pitied her.

‘I will give you three days time,’ said he, ‘if by that time you find out my name, then shall you keep your child.’

So the queen thought the whole night of all the names that she had ever heard, and she sent a messenger over the country to inquire, far and wide, for any other names that there might be. When the manikin came the next day, she began with Caspar, Melchior, Balthazar, and said all the names she knew, one after another, but to every one the little man said, ‘That is not my name.’

On the second day she had inquiries made in the neighborhood as to the names of the people there, and she repeated to the manikin the most uncommon and curious. Perhaps your name is Shortribs, or Sheepshanks, or Laceleg, but he always answered, ‘That is not my name.’

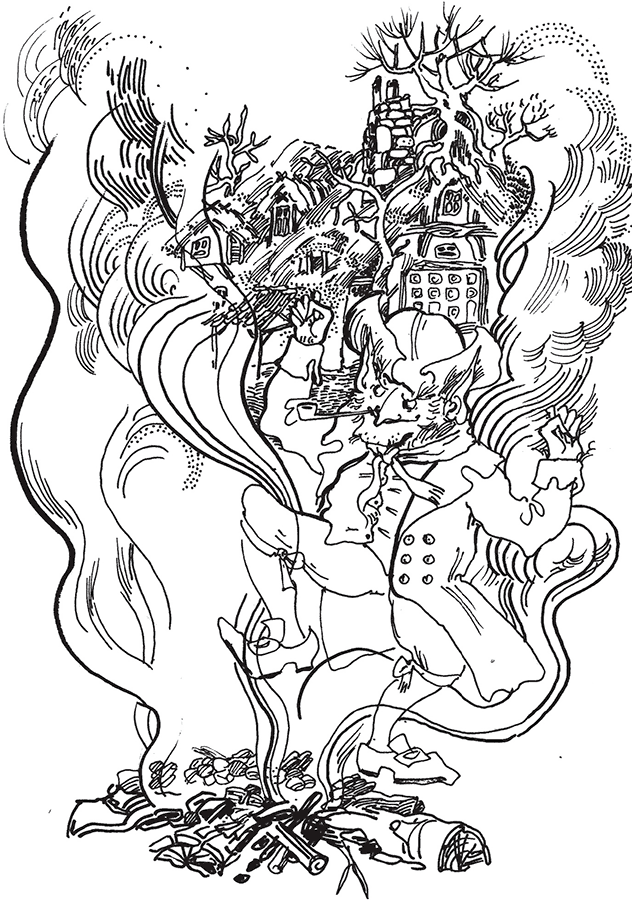

On the third day the messenger came back again, and said, ‘I have not been able to find a single new name, but as I came to a high mountain at the end of the forest, where the fox and the hare bid each other good night, there I saw a little house, and before the house a fire was burning, and round about the fire quite a ridiculous little man was jumping, he hopped upon one leg, and shouted –

‘Today I bake, tomorrow brew, the next I’ll have the young queen’s child.

Ha, glad am I that no one knew that Rumpelstiltskin I am styled.’

You may imagine how glad the queen was when she heard the name. And when soon afterwards the little man came in, and asked, ‘Now, mistress queen, what is my name?’

At first she said, ‘Is your name Conrad?’

‘No.’

‘Is your name Harry?’

‘No.’

‘Perhaps your name is Rumpelstiltskin?’

‘The devil has told you that! The devil has told you that,’ cried the little man, and in his anger he plunged his right foot so deep into the earth that his whole leg went in, and then in rage he pulled at his left leg so hard with both hands that he tore himself in two.

The Frogs and the Well

Two Frogs lived together in a marsh. But one hot summer the marsh dried up, and they left it to look for another place to live in: for frogs like damp places if they can get them. By and by they came to a deep well, and one of them looked down into it, and said to the other, ‘This looks a nice cool place. Let us jump in and settle here.’ But the other, who had a wiser head on his shoulders, replied, ‘Not so fast, my friend. Supposing this well dried up like the marsh, how should we get out again?’

Moral: Look before you leap.

Why the Sea is Salt (A. Lang)

Once upon a time, long ago there were two brothers, the one rich and the other poor. When Christmas Eve came, the poor one had not a bite in the house, either of meat or bread; so he went to his brother, and begged him, in God’s name, to give him something for Christmas Day. It was by no means the first time that the brother had been forced to give something to him, and he was not better pleased at being asked now than he generally was.

‘If you will do what I ask you, you shall have a whole ham,’ said he. The poor one immediately thanked him, and promised this.

‘Well, here is the ham, and now you must go straight to Dead Man’s Hall,’ said the rich brother, throwing the ham to him.

‘Well, I will do what I have promised,’ said the other, and he took the ham and set off. He went on and on for the livelong day, and at nightfall he came to a place where there was a bright light.

‘I have no doubt this is the place,’ thought the man with the ham.

An old man with a long white beard was standing in the outhouse, chopping logs.

‘Good-evening,’ said the man with the ham.

‘Good-evening to you. Where are you going at this late hour?’ said the man.

‘I am going to Dead Man’s Hall, if only I am on the right track,’ answered the poor man.

‘Oh! Yes, you are right enough, for it is here,’ said the old man. ‘When you get inside they will all want to buy your ham, for they don’t get much meat to eat there; but you must not sell it unless you can get the hand-mill which stands behind the door for it. When you come out again I will teach you how to stop the hand-mill, which is useful for almost everything.’

So the man with the ham thanked the other for his good advice, and rapped at the door.

When he got in, everything happened just as the old man had said it would: all the people, great and small, came round him like ants on an ant-hill, and each tried to outbid the other for the ham.

‘By rights my old woman and I ought to have it for our Christmas dinner, but, since you have set your hearts upon it, I must just give it up to you,’ said the man. ‘But, if I sell it, I will have the handmill which is standing there behind the door.’

At first they would not hear to this, and haggled and bargained with the man, but he stuck to what he had said, and the people were forced to give him the hand-mill. When the man came out again into the yard, he asked the old wood-cutter how he was to stop the hand-mill, and when he had learned that, he thanked him and set off home with all the speed he could, but did not get there until after the clock had struck twelve on Christmas Eve.

‘Where in the world have you been?’ said the old woman. ‘Here I have sat waiting hour after hour, and have not even two sticks to lay across each other under the Christmas porridge-pot.’

‘Oh! I could not come before; I had something of importance to see about, and a long way to go, too; but now you shall just see!’ said the man, and then he set the hand-mill on the table, and bade it first grind light, then a table-cloth, and then meat, and beer, and everything else that was good for a Christmas Eve’s supper; and the mill ground all that he ordered. ‘Bless me!’ said the old woman as one thing after another appeared; and she wanted to know where her husband had got the mill from, but he would not tell her that.

‘Never mind where I got it; you can see that it is a good one, and the water that turns it will never freeze,’ said the man. So he ground meat and drink, and all kinds of good things, to last all Christmas-tide, and on the third day he invited all his friends to come to a feast.

Now when the rich brother saw all that there was at the banquet and in the house, he was both vexed and angry, for he grudged everything his brother had. ‘On Christmas Eve he was so poor that he came to me and begged for a trifle, for God’s sake, and now he gives a feast as if he were both a count and a king!’ thought he. ‘But, for heaven’s sake, tell me where you got your riches from,’ said he to his brother.

‘From behind the door,’ said he who owned the mill, for he did not choose to satisfy his brother on that point; but later in the evening, when he had taken a drop too much, he could not refrain from telling how he had come by the handmill. ‘There you see what has brought me all my wealth!’ said he, and brought out the mill, and made it grind first one thing and then another. When the brother saw that, he insisted on having the mill, and after a great deal of persuasion got it; but he had to give three hundred dollars for it, and the poor brother was to keep it till the haymaking was over, for he thought: ‘If I keep it as long as that, I can make it grind meat and drink that will last many a long year.’ During that time you may imagine that the mill did not grow rusty, and when hay harvest came, the rich brother got it, but the other had taken good care not to teach him how to stop it. It was evening when the rich man got the mill home, and in the morning he bade the old woman go out and spread the hay after the mowers, and he would attend to the house himself that day, he said.

So, when dinner-time drew near, he set the mill on the kitchen-table, and said: ‘Grind herrings and milk pottage, and do it both quickly and well.’

So the mill began to grind herrings and milk pottage, and first all the dishes and tubs were filled, and then it came out all over the kitchen-floor. The man twisted and turned it, and did all he could to make the mill stop, but, howsoever he turned it and screwed it, the mill went on grinding, and in a short time the pottage rose so high that the man was like to be drowned. So he threw open the parlor door, but it was not long before the mill had ground the parlor full too, and it was with difficulty and danger that the man could go through the stream of pottage and get hold of the door-latch. When he got the door open, he did not stay long in the room, but ran out, and the herrings and pottage came after him, and it streamed out over both farm and field. Now the old woman, who was out spreading the hay, began to think dinner was long in coming, and said to the women and the mowers: ‘Though the master does not call us home, we may as well go. It may be that he finds he is not good at making pottage and I should do well to help him.’ So they began to straggle homeward, but when they had got a little way up the hill they met the herrings and pottage and bread, all pouring forth and winding about one over the other, and the man himself in front of the flood. ‘Would to heaven that each of you had a hundred stomachs! Take care that you are not drowned in the pottage!’ he cried as he went by them as if Mischief were at his heels, down to where his brother dwelt. Then he begged him, for God’s sake, to take the mill back again, and that in an instant, for, said he: ‘If it grind one hour more the whole district will be destroyed by herrings and pottage.’ But the brother would not take it until the other paid him three hundred dollars, and that he was obliged to do. Now the poor brother had both the money and the mill again. So it was not long before he had a farmhouse much finer than that in which his brother lived, but the mill ground him so much money that he covered it with plates of gold; and the farmhouse lay close by the sea-shore, so it shone and glittered far out to sea. Everyone who sailed by there now had to be put in to visit the rich man in the gold farmhouse, and everyone wanted to see the wonderful mill, for the report of it spread far and wide, and there was no one who had not heard tell of it.

After a long, long time came also a skipper who wished to see the mill. He asked if it could make salt. ‘Yes, it could make salt,’ said he who owned it, and when the skipper heard that, he wished with all his might and main to have the mill, let it cost what it might, for, he thought, if he had it, he would get off having to sail far away over the perilous sea for freights of salt. At first the man would not hear of parting with it, but the skipper begged and prayed, and at last the man sold it to him, and got many, many thousand dollars for it. When the skipper had got the mill on his back he did not stay there long, for he was so afraid that the man would change his mind, and he had no time to ask how he was to stop it grinding, but got on board his ship as fast as he could.

When he had gone a little way out to sea he took the mill on deck. ‘Grind salt, and grind both quickly and well,’ said the skipper. So the mill began to grind salt, till it spouted out like water, and when the skipper had got the ship filled he wanted to stop the mill, but whichsoever way he turned it, and how much soever he tried, it went on grinding, and the heap of salt grew higher and higher, until at last the ship sank. There lies the mill at the bottom of the sea, and still, day by day, it grinds on; and that is why the sea is salt.