Антуан де Сент-Экзюпери / Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Маленький принц / The Little Prince

Иллюстрации Е.Д. Шавиковой

© Матвеев С.А., адаптация текста, коммент., упражнения и словарь, 2019

© Шавикова Е.Д., иллюстрации

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2019

1

Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest. It was a picture of a boa which was swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing:

In the book it said: “Boas swallow their prey whole, they do not chew it. After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.”

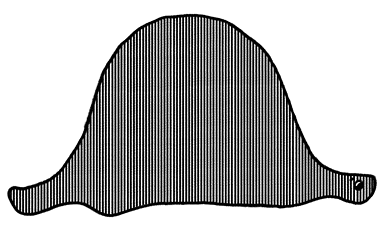

I thought about it. And then I made my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. It looked like this:

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them.

But they answered: “Frighten? Why can anyone be frightened by a hat?”

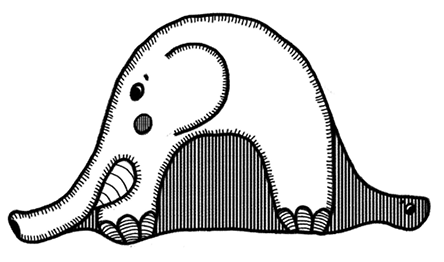

My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa which was digesting an elephant. But the grown-ups were not able to understand it. They always needed explanations. So I made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa. This time the grown-ups could see it clearly. My Drawing Number Two looked like this:

The grown-ups advised me not to draw the boas from the inside or the outside, and study geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why, at the age of six, I stopped drawing. So I did not become a famous painter. I was disheartened by the failure of my Drawing Number One and my Drawing Number Two. Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is tiresome for children to explain things to them all the time.

So I chose another profession, and became a pilot. I flew over all parts of the world; and it is true that geography was very useful to me. Now I can distinguish China from Arizona.

I have met many people. I lived among grownups. I saw them intimately, and that did not improve my opinion of them.

When I met one of them who seemed clever enough to me, I tried to show him my Drawing Number One. I tried to learn, so, if this person had true understanding. But he—or she—always said,

“That is a hat.”

Then I did not talk to that person about boas, or forests, or stars. I talked to him about bridge, and golf, and politics, and ties.

2

So I lived my life alone and had no one to talk to, until I had an accident with my plane in the Desert of Sahara, six years ago. Something broke in my engine. And I had with me neither a mechanic nor any passengers. So I began to repair it all alone. It was a question of life or death for me: I had very little drinking water.

The first night, I went to sleep on the sand, a thousand miles away from any town. I was more isolated than a sailor on a raft in the middle of the ocean. Thus you can imagine my amazement, at sunrise, when I was awakened by an odd little voice. It said:

“Will you please draw me a sheep!”

“What!”

“Draw me a sheep!”

I jumped to my feet and looked carefully all around me. And I saw a most extraordinary small person who stood there. He was examining me with great seriousness.

Remember, I crashed in the desert a thousand miles from any town. The child did not seem hungry or thirsty or frightened. He was not looking like a child lost in the middle of the desert. When at last I was able to speak, I said to him:

“But—what are you doing here?”

And he repeated, very slowly:

“Will you please draw me a sheep.”

It was absurd: in danger of death he wanted me to draw a sheep! I could not disobey. I took out of my pocket a sheet of paper and my pen. But then I remembered that I was studying geography, history, arithmetic and grammar, and I told the boy that I did not know how to draw. He answered to me:

“That doesn’t matter. Draw me a sheep.”

But I couldn’t. So I drew for him one of my drawings. It was the boa from the outside. And I was astounded to hear:

“No, no, no! I do not want an elephant inside a boa. A boa is very dangerous, and an elephant is very big. Where I live, everything is very small. What I need is a sheep. Draw me a sheep.”

So then I made a drawing.

He looked at it carefully, and then said:

“No. This sheep is very sickly. Make me another.”

So I made another drawing.

My friend smiled gently and indulgently.

“You see yourself,” he said, “that this is not a sheep. This is a ram. It has horns.”

So then I drew once more.

But it was rejected too, just like the others.

“This one is too old. I want a sheep that will live a long time.”

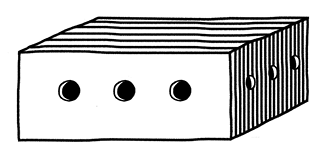

By this time my patience was exhausted, because I wanted to repair my engine. So I drew a simple box and explained:

“This is his box. Your sheep is inside.”

I was very surprised to see the face of my young judge:

“That is exactly what I wanted! Do you think that this sheep will need much grass?”

“Why?”

“Because where I live everything is very small.”

“There will be enough grass for him,” I said. “It is a very small sheep.”

He bent his head over the drawing.

“Not so small… Look! He went to sleep.”

And that is how I met the little prince.

3

It took me a long time to understand where he came from. The little prince asked me many questions, but did not hear the questions I asked him.

The first time he saw my airplane, for instance (I shall not draw my airplane; it’s too complicated for me), he asked me:

“What is that object?”

“That is not an object. It flies. It is an airplane. It is my airplane.”

And I was proud to tell him that I could fly.

He cried out, then:

“What! You dropped down from the sky?”

“Yes,” I answered, modestly.

“Oh! That is funny!”

And the little prince began to laugh, which irritated me very much. Then he added:

“So you, too, come from the sky! Which planet is yours?”

At that moment I understood the mystery of his presence; and I demanded, abruptly:

“Do you come from another planet?”

But he did not reply. He tossed his head gently. He was looking at my plane:

“It is true that on that you can’t travel very far…”

You can imagine how my curiosity was aroused! I heard about the “other planets.” I tried to learn something more.

“My little man, where do you come from? What is this ‘where I live,’ of which you speak? Where do you want to take your sheep?”

After a while he answered:

“It is very good that you gave me the box. The sheep can use it as his house.”

“That is so. And if you are good I will give you a string, too, so that you can tie him during the day, and a post to tie him to.”

But the little prince seemed shocked:

“Tie him! What a queer idea!”

“But if you don’t tie him,” I said, “he will wander off somewhere, and get lost.”

My friend laughed loudly:

“But where do you think he can go?”

“Anywhere. Straight ahead of him.”

Then the little prince said, earnestly:

“That doesn’t matter. Where I live, everything is so small!”

And, with sadness, he added:

“Straight ahead of him, nobody can go very far.”

4

Thus I learned an important fact: the little prince’s planet was no larger than a house!

But that did not really surprise me much. I knew very well that in addition to the great planets to which we gave names—such as the Earth, Jupiter, Mars, Venus—there are also hundreds of others. Some of them are very small. It’s hard to see them even through the telescope. When an astronomer discovers one of these he does not give it a name, but only a number. He might call it, for example, “Asteroid 325”.

I have serious reason to believe that the planet from which the little prince came is the asteroid known as B-612. This asteroid was seen through the telescope only once, by a Turkish astronomer, in 1909. He had presented it to the International Astronomical Congress. But he was in Turkish costume, and so nobody believed what he said.

Grown-ups are like that.

Fortunately, however, in 1920 the astronomer gave his presentation again, dressed in European costume. And this time everybody accepted his report.

Why do I tell you these details about the asteroid? Because I want to talk about the grown-ups. When you tell them that you have a new friend, they never ask you any important questions. They never say to you, “What does his voice sound like? What games does he like? Does he collect butterflies?” Instead, they demand: “How old is he? How many brothers has he? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father make?” Only from these figures they think they learn anything about him.

If you say to the grown-ups: “I saw a beautiful house made of rosy brick, with geraniums in the windows and doves on the roof,” they won’t have any idea of that house at all. You must say: “I saw a house that cost $20,000.” Then they will exclaim: “Oh, what a pretty house that is!”

Just so, you may say to them: “The proof that the little prince existed is: he was charming, he laughed, and he was looking for a sheep. If anybody wants a sheep, that is a proof that they exist.” And what will they do? They will shrug their shoulders, and say that you are a child. But if you say to them: ““The planet he came from is Asteroid B-612,” then they will be convinced.

They are like that. Children must always show great forbearance toward grown-up people.

But certainly, for us—who understand life—figures are very important. I shall begin this story like a fairy-tale. I want to say: “Once upon a time there was a little prince. He lived on a planet that was very small and he needed a sheep.”

To those who understand life, that will seem like a true story. Because I do not want anyone to read my book carelessly. I suffered much to write down these memories. Six years passed since my friend went away from me, with his sheep. And I try to describe him here, because I do not want to forget him. To forget a friend is sad. Not every one has a friend. And if I forget him, I may become like the grownups who are not interested in anything but figures.

It is for that purpose that I bought a box of paints and some pencils. It is hard to draw again at my age. I never made any pictures except those of the boa from the outside and the boa from the inside. I made these drawings when I was six. I shall certainly try to make my portraits as true as possible. But I am not sure of success. I make some errors, too, in the little prince’s height: in one place he is too tall and in another too short. And I feel some doubts about the colour of his costume.

In certain more important details I shall make mistakes, also. But that is something that will not be my fault. My friend never explained anything to me. He thought, perhaps, that I was like himself. But I, alas, do not know how to see sheep through the walls of boxes. Perhaps I am a little like the grown-ups. Maybe I grew old.