Chapter 3

He Is a Perfectly Impossible Person

However when I called on Wednesday there was a letter with the West Kensington postmark upon it, and my name scrawled across the envelope. The contents were as follows:

“SIR, – I have duly received your note, in which you claim to support my views. You quote an isolated sentence from my lecture, and appear to have some difficulty in understanding it. I should have thought that only a stupid person could have failed to grasp the point, but if it really needs explanation I shall see you at the hour named. As for your suggestions I would have you know that it is not my habit to change my views. You will kindly show the envelope of this letter to my man, Austin, when you call, as he has to take every precaution to protect me from the intrusive people who call themselves ‘journalists’.

Yours faithfully, GEORGE EDWARD CHALLENGER.”

This was the letter that I read aloud to Tarp Henry. His only remark was that I should take along some haemostatic. Some people have such extraordinary sense of humor.

A taxicab took me round in good time for my appointment. It was an imposing house at which we stopped. The door was opened by an odd person of uncertain age. He looked me up and down with a searching light blue eye.

“Expected?” he asked.

“An appointment.” I showed the envelope.

“Right!” He seemed to be a person of few words. I entered and saw a small woman. She was a bright, dark-eyed lady, more French than English in her type.

“One moment,” she said. “You can wait, Austin. May I ask if you have met my husband before?”

“No, madam, I have not had the honour.”

“Then I apologize to you in advance. I must tell you that he is an impossible person… absolutely impossible. Get quickly out of the room if he seems to be violent. Don’t argue with him. Several people have been injured. Afterwards there is a public scandal and it reflects upon me and all of us. I suppose it wasn’t about South America you wanted to see him?”

I could not lie to a lady.

“Dear me! That is the most dangerous subject. You won’t believe a word he says… But don’t tell him so, it makes him very violent. Pretend to believe him. If you find him really dangerous… ring the bell and hold him off until I come. Even at his worst I can usually control him.”

So I was conducted to the end of the passage. I entered the room and found myself face to face with the Professor.

He sat in a chair behind a broad table, which was covered with books, maps, and diagrams. His appearance made me gasp. I was prepared for something strange, but not for so overpowering a personality as this. It was his size which took one’s breath away… His head was enormous, the largest I have ever seen. His hair and beard were bluish-black, the latter was spade-shaped and rippling down over his chest. The eyes were blue-gray under great black eyebrows, very clear, very critical, and very masterful. This and a roaring voice made up my first impression of the notorious Professor Challenger.

“Well?” said he, with a most arrogant stare. “What now?”

“You were good enough to give me an appointment, sir,” said I, producing his envelope.

“Oh, you are the young person who cannot understand plain English, are you? And you approve my conclusions, as I understand?”

“Entirely, sir, entirely!” I was very emphatic.

“Dear me! That strengthens my position very much, does it not? Well, at least you are better than that herd of swine in Vienna.”

“They seem to have behaved outrageously,” said I.

“I assure you that I have no need of your sympathy. Well, sir, let us do what we can to end this visit. You had some comments to make up.”

There was such a brutal directness in his speech which made everything very difficult. Oh, my Irish wits, could they not help me now, when I needed help so sorely? He looked at me with two sharp eyes.

“Come, come!” he rumbled.

“I am, of course, a simple student,” said I, with a smile, “an earnest inquirer. At the same time, it seemed to me that you were a little severe towards your colleagues.”

“Severe? Well… I suppose you are aware,” said he, checking off points upon his fingers, “that the cranial index is a constant factor?”

“Naturally,” said I.

“And that telegony is still doubtful?”

“Undoubtedly.”

“And that the germ plasm is different from the parthenogenetic egg?”

“Surely!” I cried.

“But what does that prove?” he asked, in a gentle, persuasive voice.

“Ah, what indeed?” I murmured. “What does it prove?”

“It proves,” he roared, with a sudden blast of fury, “that you are the damned journalist, who has no more science in his head than he has truth in his reports!”

He had jumped to his feet with a mad rage in his eyes. Even at that moment of tension I found time for amazement at the discovery that he was quite a short man, his head not higher than my shoulder.

“Nonsense!” he cried, leaning forward. “That’s what I have been talking to you, sir! Scientific nonsense! Did you think you could play a trick on me? You, with your walnut of a brain? You have played a rather dangerous game, and you have lost it.”

“Look here, sir,” said I, backing to the door and opening it; “you can be as abusive as you like. But there is a limit. You shall not attack me.”

“Shall I not?” He was slowly approaching in a menacing way, “I have thrown several of journalists out of the house. You will be the fourth or fifth. Why should you not follow them?”

I could have rushed for the hall door, but it would have been too disgraceful. Besides, a little glow of righteous anger was springing up within me.

“Keep your hands off, sir. I’ll not stand it.”

“Dear me!” he cried smiling.

“Don’t be such a fool, Professor!” I cried. “What can you hope for? I’m not the man…”

It was at that moment that he attacked me. It was lucky that I had opened the door, or we should have gone through it. We did a Catharine-wheel together down the passage. My mouth was full of his beard, our arms were locked, our bodies intertwined. The watchful Austin had thrown open the hall door. We went down the front steps and rolled apart into the gutter. He sprang to his feet, waving his fists.

“Had enough?” he panted.

“You infernal bully!” I cried, as I gathered myself together.

At that moment a policeman appeared beside us, his notebook in his hand.

“What’s all this? You ought to be ashamed” said the policeman. “Well,” he insisted, turning to me, “what is it, then?”

“This man attacked me,” I said.

“Did you attack him?” asked the policeman.

The Professor breathed hard and said nothing.

“It’s not the first time, either,” said the policeman, severely. “You were in trouble last month for the same thing. Do you give him in charge, sir?”

I softened.

“No,” said I, “I do not. It was my fault. He gave me fair warning.”

The policeman closed his notebook.

“Don’t let us have any more such goings-on,” he said and left.

The Professor looked at me, and there was something humorous in his eyes.

“Come in!” said he. “I’ve not done with you yet.”

I followed him into the house. The man-servant, Austin, closed the door behind us.

Chapter 4

It’s Just The Very Biggest Thing In The World

Hardly was it shut when Mrs. Challenger ran out of the dining-room. The small woman was furious.

“You brute, George!” she screamed. “You’ve hurt that nice young man.”

“Here he is, safe and sound.”

“Nothing but scandals every week! Everyone hating and making fun of you. You’ve finished my patience. You, a man who should have been Regius Professor at a great University with a thousand students all respecting you. Where is your dignity, George? A ruffian… that’s what you have become!”

“Be good, Jessie.”

“A roaring bully!”

Challenger bellowed with laughter. Suddenly his tone altered.

“Excuse us, Mr. Malone. I called you back for some more serious purpose than to mix you up with our little domestic problems.” He suddenly gave his wife a kiss, which embarrassed me. “Now, Mr. Malone,” he continued, “this way, if you please.”

We re-entered the room which we had left so rapidly ten minutes before. The Professor closed the door carefully behind us, pointed at the arm-chair, and pushed a cigar-box under my nose.

“Now listen attentively. The reason why I brought you home again is in your answer to that policeman. It was not the answer I am accustomed to associate with your profession.”

He said it like a professor addressing his class.

“I am going to talk to you about South America,” he said and took a sketch-book out of his table. “No comments if you please. First of all, I wish you to understand that nothing I tell you now is to be repeated in any public way unless you have my permission. And that permission will probably never be given. Is that clear?”

“It is very hard… Your behaviour…”

“Then I wish you a very good morning.”

“No, no!” I cried. “So far as I can see, I have no choice.”

“Word of honour?”

“Word of honour.”

He looked at me with doubt in his eyes.

“What do I know about your honour?” said he.

“Upon my word, sir,” I cried, angrily, “I have never been so insulted in my life.”

He seemed more interested than annoyed.

“Round-headed,” he muttered. “Brachycephalic, gray-eyed, black-haired, with suggestion of the negroid. Celtic, I suppose?”

“I am an Irishman, sir.”

“That, of course, explains it. Well, you promised. You are probably aware that two years ago I made a journey to South America. You are aware… or probably, in this half-educated age, you are not aware… that the country round some parts of the Amazon is still only partially explored. It was my business to visit these little-known places and to examine their fauna. And I did a great job which will be my life’s justification. I was returning, my work accomplished, when I had occasion to spend a night at a small Indian village. The natives were Cucama Indians, an amiable but degraded race, with mental powers hardly superior to the average Londoner. I had cured some of their people, and had impressed them a lot, so that I was not surprised to find myself eagerly awaited upon my return. I understood from their gestures that someone needed my medical services. When I entered the hut I found that the sufferer had already died. He was, to my surprise, no Indian, but a white man. So far as I could understand the account of the natives, he was a complete stranger to them, and had come upon their village through the woods alone being very exhausted.”

“The man’s bag lay beside the couch, and I examined the contents. His name was written upon a tab within it… Maple White, Lake Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. Now I can say that I owe this man a lot.”

“This man had been an artist. There were some simple pictures of river scenery, a paint-box, a box of coloured chalks, some brushes, that curved bone which lies upon my inkstand, a cheap revolver, and a few cartridges. Some personal equipment he had lost in his journey. Then I noticed a sketch-book. This sketch-book. I hand it to you now, and I ask you to take it page by page and to examine the contents.”

I had opened it. The first page was disappointing, however, as it contained nothing but the picture of a very fat man, “Jimmy Colver on the Mail-boat,” written beneath it. There followed several pages which were filled with small sketches of Indians. Studies of women and babies accounted for several more pages, and then there was an unbroken series of animal drawings.

“I could see nothing unusual.”

“Try the next page,” said he with a smile.

It was a full-page sketch of a landscape in colour… the kind of painting which an open-air artist takes as a guide to a future more elaborate effort. I could see high hills covered with light-green trees. Above the hills there were dark red cliffs. They looked like an unbroken wall. Near the cliffs there was a pyramidal rock, crowned by a great tree. Behind it all, a blue tropical sky.

“Well?” he asked.

“It is no doubt a curious formation,” said I “but I am not geologist enough to say that it is wonderful.”

“Wonderful!” he repeated. “It is unique. It is incredible. No one on earth has ever dreamed of such a possibility. Now the next.”

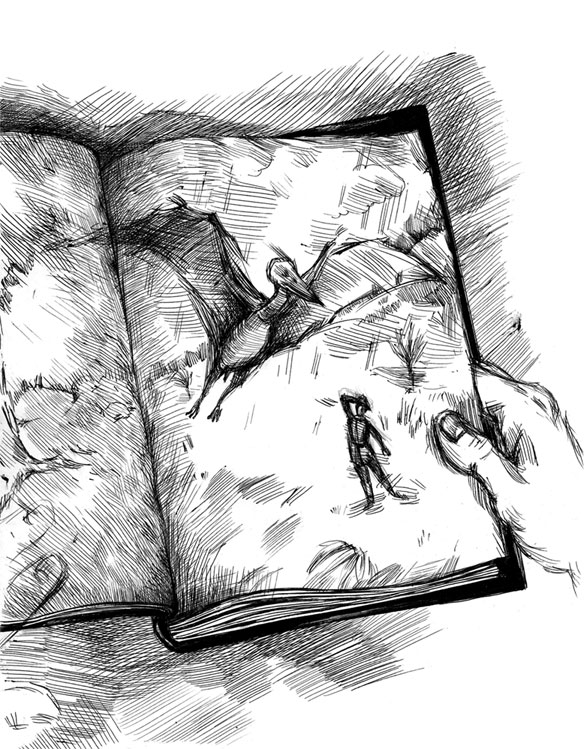

I turned it over, and gave an exclamation of surprise. There was a full-page picture of the most extraordinary creature that I had ever seen. It was the wild dream of an opium smoker. The head was like that of a bird, the body that of a large lizard. The tail was covered with sharp spikes. In front of this creature there was a small man, or dwarf, who stood looking at it.

“Well, what do you think of that?” cried the Professor, rubbing his hands with triumph.

“It is monstrous… grotesque.”

“But what made him draw such an animal?”

“Gin, I think.”

“Oh, that’s the best explanation you can give, is it?”

“Well, sir, what is yours?”

“The creature exists. That is actually sketched from the life.”

I should have laughed only that I remembered our Catharine-wheel down the passage.

“No doubt,” said I, “no doubt… But this tiny human figure puzzles me. If it were an Indian we could set it down as evidence of some pigmy race in America, but it is a European.”

“Look here!” he cried, “You see that plant behind the animal; I suppose you thought it was a flower? Well, it is a huge palm. He sketched himself to give a scale of heights.”

“Good heavens!” I cried. “Then you think the beast was so huge…”

I had turned over the leaves but there was nothing more in the book.

“… a single sketch by a wandering American artist. You can’t, as a man of science, defend such a position as that.”

For answer the Professor took a book down from a shelf.

“There is an illustration here which would interest you. Ah, yes, here it is! It is said: ‘… Jurassic Dinosaur Stegosaurus. The leg is twice as tall as a full-grown man.’ Well, what do you think of that?”

He handed me the open book. I looked at the picture. In this animal of a dead world there was certainly a very great resemblance to the sketch of the unknown artist.

“Surely it might be a coincidence…”

“Very good,” said the Professor, “I will now ask you to look at this bone.” He handed over the one which he had already described as part of the dead man’s possessions. It was about six inches long, and thicker than my thumb.

“To what known creature does that bone belong?” asked the Professor.

I examined it.

“It might be a very thick human collar-bone,” I said.

“The human collar-bone is curved. This is straight.”

“Then I don’t know what it is.”

He took a little bone the size of a bean out of a pill-box.

“This human bone is the analogue of the one which you hold in your hand. That will give you some idea of the size of the creature. What do you say to that?”

“Maybe an elephant…”

“Don’t! Don’t talk of elephants in South America! It belongs to a very large, a very strong animal which exists upon the face of the earth. You are still unconvinced?”

“I am at least deeply interested.”

“Then your case is not hopeless. We will proceed with my narrative. I could hardly come away from the Amazon without learning the truth. There were indications as to the direction from which the dead traveller had come. Indian legends would alone have been my guide, for I found that rumours of a strange land were common among all the tribes. Have you heard of Curupuri?”

“Never.”

“Curupuri is the spirit of the woods, something terrible, something to be avoided. It is a word of terror along the Amazon. Now all tribes agree as to the direction in which Curupuri lives. It was the same direction from which the American had come. Something terrible lay that way. It was my business to find out what it was.”

“I got two of the natives as guides. After many adventures we came at last to a tract of country which has never been described or visited except by the artist Maple White. Would you look at this?”

He handed me a photograph.

“This is one of the few which partially escaped – on our way back our boat was upset. There was talk of faking. I am not in a mood to argue such a point.”

The photograph was certainly very off-coloured. It represented a long and enormously high line of cliffs, with trees in the foreground.

“The same place as the painted picture…” said I.

“Yes,” the Professor answered. “We progress, do we not? Now, will you please look at the top of that rock? Do you observe something there?”

“An enormous tree.”

“But on the tree?”

“A large bird,” said I.

He handed me a lens.

“Yes,” I said, looking through it, “a large bird stands on the tree. It has a great beak. A pelican?”

“It may interest you that I shot it. It was the only absolute proof of my experiences.”

“You have it, then?”

“I had it. It was unfortunately lost in the same boat accident which ruined my photographs. Only a part of its wing was left in my hand.”

He took it out. It was at least two feet in length, a curved bone, with a membranous veil beneath it.

“A monstrous bat!” I suggested.

“Nothing of the sort,” said the Professor, severely. “The wing of a bat consists of three fingers with membranes between. Now, you can see that this is a single membrane hanging upon a single bone, and therefore that it cannot belong to a bat. What is it then?”

“I really do not know,” I said.

“Here,” said he, pointing to the picture of an extraordinary flying monster, “is an excellent reproduction of the pterodactyl, a flying reptile of the Jurassic period. On the next page is a diagram of the mechanism of its wing. Compare it with the specimen in your hand.”

A wave of amazement passed over me as I looked. I was convinced. There could be no getting away from it. The proof was overwhelming. The sketch, the photographs, the narrative, and now the actual specimen… the evidence was complete.

“It’s just the very biggest thing that I ever heard of!” I cried. “It is colossal. You have discovered a lost world! I’m awfully sorry if I seemed to doubt you.”

The Professor purred with satisfaction.

“And then, sir, what did you do next?”

“I managed to see the plateau from the pyramidal rock upon which I saw and shot the pterodactyl. It appeared to be very large; I could not see the end of it. Below, it is jungly region, full of snakes, insects, and fever. It is a natural protection to this country.”

“Did you see any other trace of life?”

“No, I did not, but we heard some very strange noises from above.”

“But what about the creature that the American drew?”

“We can only suppose that he must have made his way to the rock and seen it there. The way is a very difficult one. That’s why the creatures do not come down and overrun the surrounding country.”

“But how did they come to be there?”

“There can only be one explanation. South America is a granite continent. At this single point in the interior there has been a great, sudden volcanic upheaval. These cliffs, I may remark, are basaltic, and therefore plutonic. And a large area has been lifted up with all its living contents. What is the result? Creatures survive which would otherwise disappear. You will observe that both the pterodactyl and the stegosaurus are Jurassic. They have been artificially conserved by those strange accidental conditions.”

“Your evidence is conclusive. You have only to tell the world about it.”

“I can only tell you that I was met by incredulity, born partly of stupidity and partly of jealousy. It is not my nature, sir, to prove a fact if my word has been doubted. When men like yourself, who represent the foolish curiosity of the public, came to disturb my privacy I was unable to meet them with open arms. By nature I am fiery. I fear you may have remarked it.”

I touched my eye and was silent.

“Well, I invite you to be present at the exhibition.” Challenger handed me a card from his desk. “Mr. Percival Waldron, a naturalist of some popular repute, is to lecture at eight-thirty at the Zoological Institute’s Hall upon ‘The Record of the Ages’. I have been specially invited. Maybe a few remarks may arouse the interest of the audience. We’ll see… By all means, come. It will be a comfort to me to know that I have one ally in the hall, however inefficient and ignorant of the subject. No public use is to be made of any of the material that I have given you.”

“But Mr. McArdle… my news editor… will want to know what I have done.”

“Tell him what you like. I leave it to you that nothing of all this appears in print. Very good. Then the Zoological Institute’s Hall at eight-thirty tonight.”