Chapter 2

Next morning I missed O’Toole: he didn’t appear at breakfast, and I looked for him in vain upon the deck. There was a heavy mist over the river which the sun took a long time to disperse. I felt a little lonely without my only contact. Everyone else was settling into a shipboard relation: even a few flirtations had begun. Two old men paced the deck fiercely, showing off their physical fitness. There was something obscene to me about their rapid regular walk – they seemed to be indicating to all the women they passed that they were still in full possession of their powers. They wore slit jackets in imitation of the English – they had probably bought them at Harrods – and they reminded me of Major Charge.

We had pulled up at a town called Rosario during the night (the voices, the shouts, the noise of chains had entered my dreams and made them dreams of violence some while before I woke), and now the river, when the mist rose, had changed its character. The water was sprinkled with islands, and there were cliffs and sand bars and strange birds piping and whispering beside us. I experienced far more the sensation of travel than when I passed all the crowded frontiers in the Orient Express. The river was low, and a rumour spread that we might not be able to get beyond Corrientes because the expected rains of winter had not come. A sailor on the bridge continually swung the lead. We were within half a metre, the priest told me, of the ship’s draught, and he moved on to spread despondency further.

I began for the first time seriously to read Rob Roy, but the moving scenery was a distraction. I would begin a page while the shore was half a mile away, and when I lifted my eyes after a few paragraphs, it had approached within a stone’s throw – or was it an island? At the beginning of the next page I looked again, and the water was now nearly a mile wide. A Czech sat down beside me. He spoke English and I was content to close Rob Roy and listen to him. He was a man who, having once known prison, enjoyed freedom to the full. His mother had died under the Nazis, his father under the Communists, he had escaped to Austria and married an Austrian girl. His training had been scientific, and when he decided to settle in the Argentine he had borrowed the money to start a plastics factory. He said, “I looked around first in Brazil and Uruguay and Venezuela. One thing I noticed. Everywhere but in the Argentine they used straws for cold drinks. Not in the Argentine. I thought I’d make my fortune. I made two million plastic straws and I couldn’t sell a hundred. You want a straw? You can have two million for free. There they are stacked in my factory today. The Argentines are so conservative they won’t drink through a straw. I was very nearly bankrupt, I can tell you,” he said happily.

“So what do you do now?”

He gave me a cheerful grin. He seemed one of the happiest men I had ever met. He had shed his past fears and failures and sorrows more completely than most of us can do. He said, “I manufacture plastic material and let other fools risk their money on what they make with it.”

The man with the rabbit nose went twitching by, grey as the grey morning.

“He gets off at Formosa,” I said.

“Ah, a smuggler,” the Czech said and laughed and went on his way.

I began to read Rob Roy again while the leadsman called the sounding. “You must remember my father well; for as your own was a member of the mercantile house, you knew him from infancy. Yet you hardly saw him in his best days, before age and infirmity had quenched his ardent spirit of enterprise and speculation.” I thought of my father lying in his bath in his clothes, just as later he lay in his Boulogne coffin, and giving me his impossible instructions, and I wondered why I felt an affection for him, while I felt none for my faultless mother who had brought me up with rigid care and found me my first situation in a bank. I had never built the plinth among the dahlias and before I left home I had thrown away the empty urn. Suddenly a memory came back to me of an angry voice. I had woken up, as I sometimes did, afraid that the house was on fire and that I had been abandoned. I had climbed out of bed and sat down at the top of the stairs, reassured by the voice below. It didn’t matter how angry it was: it was there: I was not alone and there was no smell of burning. “Go away,” the voice said, “if you want to, but I’ll keep the child.”

A low reasonable voice, which I recognized as my father’s, said, “I am his father,” and the woman I knew as my mother slammed back like a closing door, “And who’s to say that I’m not his mother?”

“Good morning,” O’Toole said, sitting down beside me. “Did you sleep well?”

“Yes. And you?”

He shook his head. “I kept on thinking of Lucinda,” he said. He took out his notebook and again began to write down his mysterious columns of numerals.

“Research?” I asked.

“Oh,” he said, “this is not official.” “Making a bet on the ship’s run?”

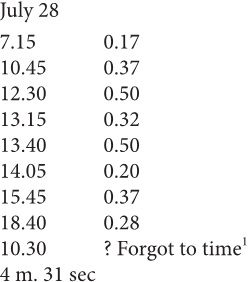

“No, no. I’m not a betting man.” He gave me one of his habitual looks of melancholy and anxiety. “I’ve never told anyone about this, Henry,” he said. “It would seem kind of funny to most people, I guess. The fact is I count while I’m pissing and then I write down how long I’ve taken and what time it is. Do you realize we spend more than one whole day a year pissing?”

“Good heavens,” I said.

“I can prove it, Henry. Look here.” He opened his notebook and showed me a page. His writing went something like this:

1

Forgot to time – (разг.) Забыл отметить время

He said, “You’ve only got to multiply by seven. That makes half an hour a week. Twenty-six hours a year. Of course shipboard life isn’t quite average. There’s more drinking between meals. And beer keeps on repeating. Look at this time here – one minute, fifty-five seconds. That’s more than the average, but then I’ve noted down two gins. There’s a lot of variations too I haven’t accounted for, and from now on I’m going to make a note of the temperature too. Here’s July twenty-fifth – six minutes, nine seconds n.c. – that stands for ‘not complete.’ I went out to dinner in BA and left my notebook at home. And here’s July twenty-seventh – only three minutes twelve seconds in all, but, if you remember, there was a very cold north wind on July twenty-fifth and I went out to dinner without an overcoat.”

“Are you drawing any conclusions?” I asked.

“That’s not my job,” he said. “I’m no expert. I just report the facts and any data – like the gins and the weather – that seem to have a bearing. It’s for others to draw the conclusions.”

“Who are the others?”

“Well, I thought when I had completed six months’ research I’d get in touch with a urinary specialist. You don’t know what he mightn’t be able to read into these figures. Those guys deal all the time with the sick. It’s important to them to know what happens in the case of an average fellow.”

“And you are the average fellow?”

“Yes. I’m a hundred per cent healthy, Henry. I have to be in my job. They give me the works every so often.”

“The CIA?” I asked.

“You’re kidding, Henry. You can’t believe that crazy girl.”

He fell into a sad silence as he thought of her, leaning forward with his chin in his hand. An island with the appearance of a gigantic alligator floated downstream with its snout extending along the water. Pale green fishing boats drifted downstream faster than our engines could drive us against the current – they passed rapidly like little racing cars. Each fisherman was surrounded by floating blocks of wood to which his lines were attached. Rivers branched off into the grey misty interior, wider than the Thames at Westminster but going nowhere at all.

He asked, “And she really called herself Tooley?”

“Yes, Tooley.”

“I guess she must think of me sometimes?” he said with a sort of questioning hope.

Chapter 3

It was two days later that we came to Formosa, on a day which was as humid as all the others had been. The heat broke on the cheek like little bubbles of water. We had turned off the great Parana river the night before near Corrientes, and now we were on the Paraguay. Fifty yards across the water from the Argentinian Formosa the other country lay, sodden and empty. The import-export man went ashore in his dark city suit carrying a new suitcase. He went with rapid steps, looking at his watch like the rabbit in Alice in Wonderland. It certainly seemed an ideal town for smugglers, with only a river to cross. In Paraguay I could see only a crumbling hut, a pig and a small girl.

I was tired of walking the deck, so I went ashore too. It was a Sunday and quite a crowd had collected to see the boat come in. There was a pervading smell of orange petals, but it was the only sweet thing about Formosa. One long avenue was lined with oranges and trees bearing rose-coloured flowers, which I learnt later to be lapachos. The side streets petered out a few yards away into a niggardly wild nature of mud and scrub. Everything to do with government, business, justice or amusement lay in the one avenue: a tourist hotel of grey cement on the water’s edge had been half-built, for what tourists? little shops selling Coca-Cola; a cinema which advertised an Italian Western; two hairdressers; a garage with one wrecked car; a cantina. The only house of more than one story was the hotel, and the only old and beautiful building in the long avenue proved, as I came closer to it, to be the prison. There were fountains all down the avenue but they didn’t play.

The avenue must lead me somewhere, I thought, but I was wrong. I passed the bust of a bearded man called Urquiza, who, judging from the carved inscription, must have had something to do with liberation – from what? – and ahead of me I saw rise up above the orange trees and the lapachos a marble man upon, a marble horse who was certainly General San Martín – Buenos Aires had made me familiar with his features and I had seen him upon the seafront at Boulogne too. The statue closed the avenue as the Arc de Triomphe closes the Champs-Elysées; I expected some further avenue beyond, but when I reached the statue I found the hero sat on his horse in a waste of mud at the farthest limit of the town. No strollers came so far, and the road went no farther. Only a starving dog, like a skeleton from the Natural History Museum, picked his way timorously across the dirt and the rain pools towards me and San Martín. I began to walk back.

If I describe this ignoble little town in such detail, it is because it was the scene of a long dialogue I held with myself which was interrupted only by a surprising encounter. I had begun, as I passed the first hairdresser, to think of Miss Keene and her letter of shy appeal which surely deserved a better response than my brief telegram, and then in this humid place, where the only serious business or entertainment was certainly crime, and even the national bank had to be defended on a Sunday afternoon by a guard with an automatic rifle, I thought of my home in Southwood, of my garden, of Major Charge trumpeting across the fence, and of the sweet sound of the bells from Church Road. But I remembered Southwood now with a kind of friendly tolerance – as the place which Miss Keene should never have left, the place where Miss Keene was happy, the place where I myself no longer belonged. It was as though I had escaped from an open prison, had been snatched away, provided with a rope ladder and a waiting car, into my aunt’s world, the world of the unexpected character and the unforeseen event. There the rabbit-faced smuggler was at home, the Czech with his two million plastic straws, and poor O’Toole busy making a record of his urine.

I passed the end of a street called Rua Dean Furnes which petered away like all the others into no-man’s-land, and I stayed a moment outside the governor’s house, which was painted with a pink wash. On the veranda were two unoccupied chaises-longues and the windows were wide open on an empty room with a portrait of a military man, the President, I suppose, and a row of empty chairs lined up against the wall like a firing squad. The sentry made a small movement with his automatic rifle and I moved on towards the national bank, where another sentry made the same warning movement when I paused.

That morning in my bunk I had read Wordsworth’s great ode in Palgrave’s Golden Treasury. Palgrave, like Scott, carried signs of my father’s reading in the form of dog-eared pages, and knowing so little about him, I had followed every clue and so learned to enjoy what he had enjoyed. Thus when I first entered the bank as junior clerk I had thought of it in Wordsworth’s terms as a “prison-house” – what was it my father had found a prison, so that he double-marked the passage? Perhaps our home, and my stepmother and I had been the warders.

One’s life is more formed, I sometimes think, by books than by human beings: it is out of books one learns about love and pain at second hand. Even if we have the happy chance to fall in love, it is because we have been conditioned by what we have read, and if I had never known love at all, perhaps it was because my father’s library had not contained the right books. (I don’t think there was much passionate love in Marion Crawford, and only a shadow of it in Walter Scott.)

I can remember very little of the vision preceding the prison-house: it must have faded very early “into the light of common day,” but it seemed to me, as I put Palgrave down beside my bunk and thought of my aunt, that she for one had never allowed the vision to fade. Perhaps a sense of morality is the sad compensation we learn to enjoy, like a remission for good conduct. In the vision there is no morality. I had been born as a result of what my stepmother would have called an immoral act, an act of darkness. I had begun in immoral freedom. Why then should I have found myself in a prison-house? My real mother had certainly not been imprisoned anywhere.

It’s too late now, I said to Miss Keene, signalling to me desperately from Koffiefontein, I’m no longer there, where you think I am. Perhaps we might have comforted ourselves once and been content in our prison cell, but I’m not the same man you regarded with a touch of tenderness over the tatting. I have escaped. I don’t resemble whatever identikit portrait you have of me. I walked back towards the landing stage, and looking behind me, I saw the canine skeleton on my tracks. I suppose to that dog any stranger represented hope.

“Hi, man,” a voice called. “You in number-one hurry?” and Wordsworth was suddenly there a few yards away. He had risen from a bench beside the bust of the liberator Urquiza and advanced towards me with both hands out and his face slashed open with the wide wound of his grin. “Man, you not forget old Wordsworth?” he asked, wringing both my hands, and laughing so loudly and deeply that he sprayed my face with his happiness.

“Why, Wordsworth,” I said with equal pleasure, “what on earth are you doing here?”

“My lil bebi gel,” he said, “she tell me go off Formosa and wait for Mr. Pullen come.”

I noticed that he was every bit as smartly dressed now as the rabbit-nosed importer and he too carried a very new suitcase.

“How is my aunt, Wordsworth?”

“She pretty O.K.,” he said, but there was a look of distress in his eyes and he added, “She dance one hell too much. Ar tell her she no bebi gel no more. Ef she no go stop… Man, she got me real worried.”

“Are you coming on the boat with me?”

“Ar sure am, Mr. Pullen. You lef every ting to old Wordsworth. Ar know the customs fellows in Asunción. Some good guys. Some bad like hell. You lef me talk. We don wan no humbug.”

“I’m not smuggling anything, Wordsworth.” The noise of the ship’s siren summoned us, wailing up from the river.

“Man, you lef everyting to old Wordsworth. Ar jus gone tak a look at that boat and ar see a real bad guy there. We gotta be careful.”

“Careful of what, Wordsworth?”

“You in good hands, Mr. Pullen. You lef old Wordsworth be now.”

He suddenly took my fingers and pressed them. “You got that picture, Mr. Pullen?”

“You mean of Freetown harbour? Yes, I’ve got that.”

He gave a sigh of satisfaction. “Ar lak you, Mr. Pullen. You allays straight with old Wordsworth. Now you go for boat.” I was just leaving him when he added, “You got CTC for Wordsworth?” and I gave him what coins I had in my pocket. Whatever trouble he might have caused me in that dead old world of mine, I was overjoyed to see him now.

They were carrying the last cargo on to the ship through the black iron doors open in the side. I made my way through the steerage quarters, where women with Indian faces sat around suckling their children and climbed the rusting stairs to the first-class. I never noticed Wordsworth come on board, and at dinner he was nowhere to be seen. I supposed that he was travelling in the steerage and saving for other purposes the difference in the fare, for I was quite certain that my aunt would have given him a first-class ticket.

After dinner O’Toole suggested a drink in his cabin. “I’ve got some good bourbon,” he said, and though I have never been a spirit-drinker, preferring a glass of sherry before a meal or a glass of port after it, I accepted his invitation gladly, for it was our last night together on board. Again the spirit of restlessness had taken over all the passengers in the ship, and they seemed touched with a kind of mania. In the saloon an amateur band had begun to play, and a sailor with hairy legs and arms, dressed inadequately as a woman, had whirled in a dance between the tables, demanding a partner. Now in the captain’s cabin, which was close to O’Toole’s, someone was playing the guitar and a woman squealed. It wasn’t what you expected to hear from a captain’s quarters.

“No one will sleep tonight,” O’Toole remarked, pouring out the bourbon.

“If you don’t mind,” I said, “a lot more soda.”

“We’ve made it. I thought we were going to be stuck fast at Corrientes. The rain is damn late this year,” and as though to soften his rebuke of the weather there came a long peal of thunder which almost drowned the music of the guitar.

“What did you think of Formosa?” O’Toole asked.

“There wasn’t much to see. Except the prison. A fine colonial building.”

“Not so good inside,” O’Toole said. A splash of lightning was flung over the wall and made the cabin lights flicker. “Met a friend, didn’t you?”

“A friend?”

“I saw you talking to a coloured guy.”

What was it that made me cautious, for I liked O’Toole? I said, “Oh, he wanted money. I didn’t see you on shore.”

“I was up on the bridge,” O’Toole said, “looking through the captain’s glasses.” He changed course abruptly. “I can’t get over you knowing my daughter, Henry. You can’t imagine how I miss that girl. You never told me how she looked.”

“She looked fine. She’s a very pretty girl.”

“Yeah,” he said, “so was her mother. If I ever married again I’d marry a plain girl.” He brooded a long time over the bourbon, and I looked around his cabin. He had made no attempt, as I had made the first day, to make it a temporary home. His suitcases lay on the floor filled with clothes; he had not bothered to hang them. A razor beside the wash-basin and a Bantam book beside his bed seemed to be the extent of his unpacking. Suddenly the rain hit the deck outside like a cloudburst.

“I guess winter’s here all right,” he said.

“Winter in July.”

“I’ve gotten used to it,” he said. “I haven’t seen the snow for six years.”

“You’ve been out here for six years?”

“No, but I was in Thailand before this.”

“Doing research?”

“Yeah. Sort of…” If he was usually as tongue-tied as this it must have taken him a long time to unearth every fact he required.

“How are the urine statistics?”

“More than four minutes thirty seconds today,” he said. He added glumly, “And I haven’t reached the end,” lifting the bourbon. When the next peal of thunder had trembled out he went on, obviously straining after any subject to fill the pause, “So you didn’t like Formosa?”

“No. Of course it may be all right for fishing,” I said.

“Fishing!” he exclaimed with scorn. “Smuggling is what you mean.”

“I keep on hearing all the time about smuggling. Smuggling what?”

“It’s the national industry of Paraguay,” he said. “It brings in nearly as much as the maté and a lot more than hiding war criminals with Swiss bank accounts. And a darn sight more than my research.”

“What have they got to smuggle?”

“Scotch whisky and American cigarettes. You get yourself an agent in Panama who buys wholesale and he flies the stuff down to Asunción. They are marked GOODS IN TRANSIT, see. You pay only a small duty at the international airport and you transfer the crates to a private plane. You’d be surprised to see how many private Dakotas there are now in Asunción. Then your pilot takes off to Argentina just across the river. At some estancia a few hundred kilometres from BA you touch down – they nearly all have private landing grounds. Not built for Dakotas perhaps, but that’s the pilot’s risk. You unload into trucks and there you are. You’ve got your distributors waiting with their tongues hanging out. The government makes them thirsty with duties of a hundred and twenty per cent.”

“And Formosa?”

“Oh, Formosa’s for the small guy working himself up on the river traffic. All the goods that arrive from Panama don’t go on in the Dakota. What do the police care if some of the crates stay behind? You’ll buy Scotch cheaper in the stores at Asunción than you will in London and the street boys will sell you good American cigarettes at cut-rate. All you need’s a rowboat and a contact. One day, though, you’ll get tired of that game – perhaps a bullet’s come too close – and you’ll buy a share in a Dakota and then you’re in the big money. You tempted, Henry?”

“I didn’t have the right training at the bank,” I said, but I thought of my aunt and her suitcases stuffed with notes and her gold brick – perhaps there was something in my blood to which a career like that might once have appealed. “You know a lot about it,” I said.

“It’s part of my sociological research.”

“Did you never think of researching a bit deeper? The frontier spirit, Tooley.” I teased him only because I liked him. I could never have teased Major Charge or the admiral in that way.

He gave me a long sad look, as though he wanted to answer me quite truthfully. “You don’t save enough money in a job like mine to buy a Dakota. And the risks are big too, Henry, for a foreigner. These guys fall out sometimes and then there’s hijacking. Or the police get greedy. It’s easy to disappear in Paraguay – not necessarily disappear either. Who’s going to make a fuss about an odd body or two? The General keeps the peace – that’s what people want after the civil war they had – and a dead man makes no trouble for anyone. They don’t have coroners in Paraguay.”

“So you prefer life to the frontier spirit, Tooley.”

“I know I’m not much good for my girl three thousand miles away, Henry, but at least she gets her monthly cheque. A dead man can’t write a cheque.”

“And I suppose the CIA aren’t interested?”

“You shouldn’t believe that nonsense, Henry. I told you – Lucinda’s romantic. She wants an exciting father, and what’s she got? She’s saddled with me. So she has to invent things. A report on malnutrition’s not romantic.”

“I think you ought to bring her home, Tooley.”

“Where’s home?” he said, and I looked around the cabin and wondered too. I don’t know why I wasn’t quite convinced. He was a great deal more reliable than she was.

I left him with his Old Forester and returned to my cabin on the opposite deck. O’Toole was port and I was starboard. I looked out at Paraguay and he looked out at Argentina. The guitar was still playing in the captain’s cabin and someone was singing in a language I couldn’t recognize – perhaps it was Guaraní. I hadn’t locked my door, and yet it wouldn’t open when I pushed. I had to put my shoulder to it to make it give. Through the crack I saw Wordsworth. He faced the door and he had a knife in his hand. When he saw who it was he held the knife down. “Come in, boss,” he said in a whisper.

“How can I come in?”

He had wedged the door with a chair. He removed it now and let me in.

“Ar got to be careful, Mr. Pullen,” he said.

“Careful of what?”

“Too much bad people on this boat, too much humbug.”

His knife was a boy’s knife with three blades and a corkscrew and a tin-opener and something for taking stones out of horses’ hoofs – cutlers are conservative and so are schoolboys. Wordsworth closed it and put it in his pocket.

“Well,” I said, “what do you want, you happy shepherd boy?”

He shook his head. “Oh, she’s a wonder, your auntie. No one ever talk to Wordsworth like that befo. Why, she come right up to me in the street outside the movie palace an she say, clear like day, ‘Thou child of joy.’ Ar love your auntie, Mr. Pullen. Ar ready to die for her any time she raise a finger an say, ‘Wordsworth, you go die.’”

“Yes, yes,” I said, “that’s fine, but what are you doing barricaded in my cabin?”

“Ar come for the picture,” he said.

“Couldn’t you wait till we get ashore?”

“Your auntie say bring that picture safe, Wordsworth, double quick, or you no come here no more”.

A suspicion returned to me. Could the frame, like the candle, be made of gold? Or did the photograph cover some notes of a very high denomination? Neither seemed likely, but neither was impossible with my aunt.

“Ar got friends in customs,” Wordsworth said, “they no humbug me, but, Mr. Pullen, you a stranger here.”

“It’s only a photograph of Freetown harbour.”

“Ya’as, Mr. Pullen. But your auntie say…”

“All right. Take it then. Where are you sleeping?”

Wordsworth jerked his thumb at the floor. “Ar more comfortable down below there, Mr. Pullen. The folks thar they sing an dance an have good time. They don wear no cravats an they no don go wash befo meals. Ar don like soap with my chop.”

“Have a cigarette, Wordsworth.”

“If you don mind, Mr. Pullen, I smoke this here.”

He pulled a ragged reconstructed cigarette out of a crumpled pocket.

“Still on pot, Wordsworth?”

“Well, it’s a sort of medicine, Mr. Pullen. Arm not too well these days. Ar got a lot o’ worry.”

“Worry about what?”

“Your auntie, Mr. Pullen. She allays safe with old Wordsworth. Ar no cost her nothing. But she got a fellah now – he cost her plenty plenty. An he too old for her, Mr. Pullen. Your auntie no chicken. She need a young fellah.”

“You aren’t exactly young yourself, Wordsworth.”

“Ar no got ma big feet in no tomb, Mr. Pullen, lak that one. Ar no trust that fellah. When we come here he plenty sick. He say, ‘Please Wordsworth, please Wordsworth,’ an he mak all the sugar in the world melt in his mouth. He live in low-class hotel, but he ain got no money. They go to turn him out an, man, he were plenty scared to go. When your auntie come he cry like a lil bebi. He no man, sure he no man, but he plenty plenty mean. He say sweet things all right all right, but he allays act mean. What wan she leave Wordsworth for a mean man like him? Tell me that, man, tell me that.” He let his great bulk down on my bed and he began to weep. It was like a spring forcing its hard way to the surface, spilling out of the crevices of a rock.

“Wordsworth,” I said, “are you jealous of Aunt Augusta?”

“Man,” he said, “she war my bebi gel. Now she gon bust ma heart in bits.”

“Poor Wordsworth.” There was nothing more I could say.

“She wan me quit,” Wordsworth said. “She wan me for come bring you, and then she wan me quit. She say, ‘I give you biggest CTC you ever saw, you go back Freetown and find a gel,’ but I no wan her money, Mr. Pullen, I no wan Freetown no more, and I no wan any gel. I love your auntie. I wan for to stay with her like the song say: ‘Abide with me; fast falls the eventide; the darkness deepens: oh, with me abide… Tears have no bitterness,’ but man, these tears are bitter, tha’s for sure.”

“Wherever did you learn that hymn, Wordsworth?”

“We allays sang that in Saint George’s cathedral in Freetown. ‘Fast falls the eventide.’ Plenty sad songs like that we sang there, an they all mak me think now of my bebi gel. ‘Here lingrin still we ask for nought but simply worship thee.’ Man, it’s true. But now she wan me to quit, an go right away an never see her no more.”

“Who is this man she’s with, Wordsworth?”

“I won spik his name. My tongue burn up if I spik his name. Oh, man, I bin faithful to your auntie long time now.”

It was to distract him from his misery and not to reproach him that I said, “You remember that girl in Paris?”

“That one who wan do jig-jig?”

“No, no, not that one. The young girl on the train.”

“Oh ya’as. Sure. I member her.”

“You gave her pot,” I said.

“Sure. Why not? Very good medicine. You don think I do anytin bad with her? Why, man, she was the ship that gone by one day. She too young for old Wordsworth.”

“Her father’s on the boat now.”

He looked at me with astonishment. “You don say!”

“He was asking me about you. He saw us on shore.”

“What he look lak?”

“He’s as tall as you but very thin. He looks unhappy and worried and he wears a tweed sports coat.”

“Oh, God Almighty! I know him. I seen him plenty in Asunción. You got to be bloody careful of him.”

“He says he’s doing social-research work.”

“What that mean?”

“He investigates things.”

“Oh, man, you’re right there. I tell you sometin. Your auntie’s fellah – he don like that man around.”

I had meant to distract him, and I had certainly succeeded. He pressed my hand hard when he left me, carrying the picture concealed under his shirt. He said, “Man, you know what you are to Wordsworth. You help of the helpless, Mr. Pullen. O abide with me.”