11

Exhibit number two is a pocket diary bound in black imitation leather, with a golden year, 1947, en escalier, in its upper left-hand corner. I speak of this neat product of the Blank Blank Go, Blankton, Mass, as if it were really before me. Actually, it was destroyed five years ago and what we examine now (by courtesy of a photographic memory) is but its brief materialization, a puny unfledged phoenix.

I remember the thing so exactly because I wrote it really twice. First I jotted down each entry in pencil (with many erasures and corrections) on the leaves of what is commercially known as a ‘typewriter tablet’; then, I copied it out with obvious abbreviations in my smallest, most satanic, hand in the little black book just mentioned.

May 30 is a Fast Day by Proclamation in New Hampshire but not in the Carolinas. That day an epidemic of ‘abdominal flu’ (whatever that is) forced Ramsdale to close its schools for the summer. The reader may check the weather data in the Ramsdale Journal for 1947. A few days before that I moved into the Haze house, and the little diary which I now propose to reel off (much as a spy delivers by heart the contents of the note he swallowed) covers most of June.

Thursday. Very warm day. From a vantage point (bathroom window) saw Dolores taking things off a clothes line in the apple-green light behind the house. Strolled out. She wore a plaid shirt, blue jeans and sneakers. Every movement she made in the dappled sun plucked at the most secret and sensitive chord of my abject body. After a while she sat down next to me on the lower step of the back porch and began to pick up the pebbles between her feet – pebbles, my God, then a curled bit of milk-bottle glass resembling a snarling lip – and chuck them at a can. Ping. You can’t a second time – you can’t hit it – this is agony – a second time. Ping. Marvellous skin – oh, marvellous: tender and tanned, not the least blemish. Sundaes cause acne. The excess of the oily substance called sebum which nourishes the hair follicles of the skin creates, when too profuse, an irritation that opens the way to infection. But nymphets do not have acne although they gorge themselves on rich food. God, what agony, that silky shimmer above her temple grading into bright brown hair. And the little bone twitching at the side of her dust-powdered ankle. ‘The McCoo girl? Ginny McCoo? Oh, she’s a fright. And mean. And lame. Nearly died of polio.’ Ping. The glistening tracery of down on her forearm. When she got up to take in the wash, I had a chance of adoring from afar the faded seat of her rolled-up jeans. Out of the lawn, bland Mrs. Haze, complete with camera, grew up like a fakir’s fake tree and after some heliotropic fussing – sad eyes up, glad eyes down – had the cheek of taking my picture as I sat blinking on the steps, Humbert le Bel.

Friday. Saw her going somewhere with a dark girl called Rose. Why does the way she walks – a child, mind you, a mere child! – excite me so abominably? Analyse it. A faint suggestion of turned-in toes. A kind of wiggly looseness below the knee prolonged to the end of each footfall. The ghost of a drag. Very infantile, infinitely meretricious. Humbert Humbert is also infinitely moved by the little one’s slangy speech, by her harsh high voice. Later heard her volley crude nonsense at Rose across the fence. Twanging through me in a rising rhythm. Pause. ‘I must go now, kiddo.’

Saturday. (Beginning perhaps amended.) I know it is madness to keep this journal but it gives me a strange thrill to do so; and only a loving wife could decipher my microscopic script. Let me state with a sob that today my L. was sun-bathing on the so-called ‘piazza’, but her mother and some other woman were around all the time. Of course, I might have sat there in the rocker and pretended to read. Playing safe, I kept away, for I was afraid that the horrible, insane, ridiculous and pitiful tremor that palsied me might prevent me from making my entrée with any semblance of casualness.

Sunday. Heat ripple still with us; a most favonian week. This time I took up a strategic position, with obese newspaper and new pipe, in the piazza rocker before L. arrived. To my intense disappointment she came with her mother, both in two-piece bathing suits, black, as new as my pipe. My darling, my sweetheart stood for a moment near me – wanted the funnies – and she smelt almost exactly like the other one, the Riviera one, but more intensely so, with rougher overtones – a torrid odour that at once set my manhood astir – but she had already yanked out of me the coveted section and retreated to her mat near her phocine mamma. There my beauty lay down on her stomach, showing me, showing the thousand eyes wide open in my eyed blood, her slightly raised shoulder blades, and the bloom along the incurvation of her spine, and the swellings of her tense narrow nates clothed in black, and the seaside of her schoolgirl thighs. Silently, the seventh-grader enjoyed her green-red-blue comics. She was the loveliest nymphet green-red-blue Priap himself could think up. As I looked on, through prismatic layers of light, dry-lipped, focusing my lust and rocking slightly under my newspaper, I felt that my perception of her, if properly concentrated upon, might be sufficient to have me attain a beggar’s bliss immediately; but, like some predator that prefers a moving prey to a motionless one, I planned to have this pitiful attainment coincide with one of the various girlish movements she made now and then as she read, such as trying to scratch the middle of her back and revealing a stippled armpit – but fat Haze suddenly spoiled everything by turning to me and asking me for a light, and starting a make-believe conversation about a fake book by some popular fraud.

Monday. Delectatio morosa. I spend my doleful days in dumps and dolours. We (mother Haze, Dolores and I) were to go to Our Glass Lake this afternoon, and bathe, and bask; but a nacreous morn degenerated at noon into rain, and Lo made a scene.

The median age of pubescence for girls has been found to be thirteen years and nine months in New York and Chicago. The age varies for individuals from ten, or earlier, to seventeen. Virginia was not quite fourteen when Harry Edgar possessed her. He gave her lessons in algebra. Je m’imagine cela. They spent their honeymoon at Petersburg, Fla. ‘Monsieur Poe-poe’, as that boy in one of Monsieur Humbert Humbert’s classes in Paris called the poet-poet.

I have all the characteristics which, according to writers on the sex interests of children, start the responses stirring in a little girl: clean-cut jaw, muscular hand, deep sonorous voice, broad shoulder. Moreover, I am said to resemble some crooner or actor chap on whom Lo has a crush.

Tuesday. Rain. Lake of the Rains. Mamma out shopping. L., I knew, was somewhere quite near. In result of some stealthy manoeuvring, I came across her in her mother’s bedroom. Prying her left eye open to get rid of a speck of something. Checked frock. Although I do love that intoxicating brown fragrance of hers, I really think she should wash her hair once in a while. For a moment, we were both in the same warm green bath of the mirror that reflected the top of a poplar with us in the sky. Held her roughly by the shoulders, then tenderly by the temples, and turned her about. ‘It’s right there,’ she said, ‘I can feel it.’ ‘Swiss peasant would use the tip of her tongue.’ ‘Lick it out?’ ‘Yeth. Shly try?’ ‘Sure,’ she said. Gently I pressed my quivering sting along her rolling salty eyeball. ‘Goody-goody,’ she said nictating. ‘It is gone.’ ‘Now the other?’ ‘You dope,’ she began, ‘there is noth – ’ but here she noticed the pucker of my approaching lips. ‘Okay,’ she said co-operatively, and bending toward her warm upturned russet face sombre Humbert pressed his mouth to her fluttering eyelid. She laughed, and brushed past me out of the room. My heart seemed everywhere at once. Never in my life – not even when fondling my child-love in France – never —

Night. Never have I experienced such agony. I would like to describe her face, her ways – and I cannot, because my own desire for her blinds me when she is near, I am not used to being with nymphets, damn it. If I close my eyes I see but an immobilized fraction of her, a cinematographic still, a sudden smooth nether loveliness, as with one knee up under her tartan skirt she sits tying her shoe. ‘Dolores Haze, ne montrez pas vos zhambes’ (this is her mother who thinks she knows French).

A poet à mes heures, I composed a madrigal to the soot-black lashes of her pale-grey vacant eyes, to the five asymmetrical freckles of her bobbed nose, to the blonde down of her brown limbs; but I tore it up and cannot recall it today. Only in the tritest of terms (diary resumed) can I describe Lo’s features: I might say her hair is auburn, and her lips as red as licked red candy, the lower one prettily plump – oh, that I were a lady writer who could have her pose naked in a naked light! But instead I am lanky, big-boned, woolly-chested Humbert Humbert, with thick black eyebrows and a queer accent, and a cesspoolful of rotting monsters behind his slow boyish smile. And neither is she the fragile child of a feminine novel. What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet – of every nymphet, perhaps; this mixture in my Lolita of tender dreamy childishness and a kind of eerie vulgarity, stemming from the snub-nosed cuteness of ads and magazine pictures, from the blurry pinkness of adolescent maidservants in the Old Country (smelling of crushed daisies and sweat); and from very young harlots disguised as children in provincial brothels; and then again, all this gets mixed up with the exquisite stainless tenderness seeping through the musk and the mud, through the dirt and the death, oh God, oh God. And what is most singular is that she, this Lolita, my Lolita, has individualized the writer’s ancient lust, so that above and over everything there is – Lolita.

Wednesday. ‘Look, make Mother take you and me to Our Glass Lake tomorrow.’ These were the textual words said to me by my twelve-year-old flame in a voluptuous whisper, as we happened to bump into one another on the front porch, I out, she in. The reflection of the afternoon sun, a dazzling white diamond with innumerable iridescent spikes quivered on the round back of a parked car. The leafage of a voluminous elm played its mellow shadows upon the clapboard wall of the house. Two poplars shivered and shook. You could make out the formless sound of remote traffic; a child calling ‘Nancy, Nan-cy!’ In the house, Lolita had put on her favourite ‘Little Carmen’ record which I used to call ‘Dwarf Conductors’, making her snort with mock derision at my mock wit.

Thursday. Last night we sat on the piazza, the Haze woman, Lolita and I. Warm dusk had deepened into amorous darkness. The old girl had finished relating in great detail the plot of a movie she and L. had seen sometime in the winter. The boxer had fallen extremely low when he met the good old priest (who had been a boxer himself in his robust youth and could still slug a sinner). We sat on cushions heaped on the floor, and L. was between the woman and me (she had squeezed herself in, the pet). In my turn, I launched upon a hilarious account of my arctic adventures. The muse of invention handed me a rifle and I shot a white bear who sat down and said: Ah! All the while I was acutely aware of L.’s nearness and as I spoke I gestured in the merciful dark and took advantage of those invisible gestures of mine to touch her hand, her shoulder and a ballerina of wool and gauze which she played with and kept sticking into my lap; and finally, when I had completely enmeshed my glowing darling in this weave of ethereal caresses, I dared stroke her bare leg along the gooseberry fuzz of her shin, and I chuckled at my own jokes, and trembled, and concealed my tremors, and once or twice felt with my rapid lips the warmth of her hair as I treated her to a quick nuzzling, humorous aside and caressed her plaything. She, too, fidgeted a good deal so that finally her mother told her sharply to quit it and sent the doll flying into the dark, and I laughed and addressed myself to Haze across Lo’s legs to let my hand creep up my nymphet’s thin back and feel her skin through her boy’s shirt.

But I knew it was all hopeless, and was sick with longing, and my clothes felt miserably tight, and I was almost glad when her mother’s quiet voice announced in the dark: ‘And now we all think that Lo should go to bed.’ ‘I think you stink,’ said Lo. ‘Which means there will be no picnic tomorrow,’ said Haze. ‘This is a free country,’ said Lo. When angry Lo with a Bronx cheer had gone, I stayed on from sheer inertia, while Haze smoked her tenth cigarette of the evening and complained of Lo.

She had been spiteful, if you please, at the age of one, when she used to throw her toys out of her crib so that her poor mother should keep picking them up, the villainous infant! Now, at twelve, she was a regular pest, said Haze. All she wanted from life was to be one day a strutting and prancing baton twirler or a jitterbug. Her grades were poor, but she was better adjusted in her new school than in Pisky (Pisky was the Haze home town in the Middle West. The Ramsdale house was her late mother-in-law’s. They had moved to Ramsdale less than two years ago). ‘Why was she unhappy there?’ ‘Oh,’ said Haze, ‘poor me should know, I went through that when was a kid: boys twisting one’s arm, banging into one with loads of books, pulling one’s hair, hurting one’s breasts, flipping one’s skirt. Of course, moodiness is a common concomitant of growing up, but Lo exaggerates. Sullen and evasive. Rude and defiant. Stuck Viola, an Italian schoolmate, in the seat with a fountain pen. Know what I would like? If you, monsieur, happened to be still here in the fall, I’d ask you to help her with her homework – you seem to know everything, geography, mathematics, French.’ ‘Oh, everything,’ answered monsieur. ‘That means,’ said Haze quickly, ‘you’ll be here!’ I wanted to shout that I would stay on eternally if only I could hope to caress now and then my incipient pupil. But I was wary of Haze. So I just grunted and stretched my limbs non-concomitantly (le mot juste) and presently went up to my room. The woman, however, was evidently not prepared to call it a day. I was already lying upon my cold bed, both hands pressing to my face Lolita’s fragrant ghost, when I heard my indefatigable landlady creeping steathily up to my door to whisper through it – just to make sure, she said, I was through with the Glance and Gulp magazine I had borrowed the other day. From her room Lo yelled she had it. We are quite a lending library in this house, thunder of God.

Friday. I wonder what my academic publishers would say if I were to quote in my textbook Ronsard’s ‘la vermeillette fente’ or Remy Belleau’s ‘un petit mont feutre de mousse delicate, trace sur le milieu d’un fillet escarlatte’ and so forth. I shall probably have another breakdown if I stay any longer in this house, under the strain of this intolerable temptation, by the side of my darling – my darling – my life and my bride. Has she already been initiated by mother nature to the Mystery of the Menarche? Bloated feeling. The Curse of the Irish. Falling from the roof. Grandma is visiting. ‘Mr. Uterus [I quote from a girls’ magazine] starts to build a thick soft wall on the chance a possible baby may have to be bedded down there.’ The tiny madman in his padded cell.

Incidentally: if I ever commit a serious murder… Mark the ‘if’. The urge should be something more than the kind of thing that happened to me with Valeria. Carefully mark that then I was rather inept. If and when you wish to sizzle me to death, remember that only a spell of insanity could ever give me the simple energy to be a brute (all this amended, perhaps). Sometimes I attempted to kill in my dreams. But do you know what happens? For instance I hold a gun. For instance I aim at a bland, quietly interested enemy. Oh, I press the trigger all right, but one bullet after another feebly drops on the floor from the sheepish muzzle. In those dreams, my only thought is to conceal the fiasco from my foe, who is slowly growing annoyed.

At dinner tonight the old cat said to me with a sidelong gleam of motherly mockery directed at Lo (I had just been describing, in a flippant vein, the delightful little toothbrush moustache I had not quite decided to grow): ‘Better don’t, if somebody is not to go absolutely dotty.’ Instantly Lo pushed her plate of boiled fish away, all but knocking her milk over, and bounced out of the dining room. ‘Would it bore you very much,’ quoth Haze, ‘to come with us tomorrow for a swim in Our Glass Lake if Lo apologizes for her manners?’

Later, I heard a great banging of doors and other sounds coming from quaking caverns where the two rivals were having a ripping row.

She has not apologized. The lake is out. It might have been fun.

Saturday. For some days already I had been leaving the door ajar, while I wrote in my room; but only today did the trap work. With a good deal of additional fidgeting, shuffling, scraping – to disguise her embarrassment at visiting me without having been called – Lo came in and after pottering around, became interested in the nightmare curlicues I had penned on a sheet of paper. Oh no: they were not the outcome of a bellelettrist’s inspired pause between two paragraphs; they were the hideous hieroglyphics (which she could not decipher) of my fatal lust. As she bent her brown curls over the desk at which I was sitting, Humbert the Hoarse put his arm around her in a miserable imitation of blood-relationship; and still studying, somewhat shortsightedly, the piece of paper she held, my innocent little visitor slowly sank to a half-sitting position upon my knee. Her adorable profile, parted lips, warm hair were some three inches from my bared eyetooth; and I felt the heat of her limbs through her rough tomboy clothes. All at once I knew I could kiss her throat or the wick of her mouth with perfect impunity. I knew she would let me do so, and even close her eyes as Hollywood teaches. A double vanilla with hot fudge – hardly more unusual than that. I cannot tell my learned reader (whose eyebrows, I suspect, have by now travelled all the way to the back of his bald head), I cannot tell him how the knowledge came to me; perhaps my ape-ear had unconsciously caught some slight change in the rhythm of her respiration – for now she was not really looking at my scribble, but waiting with curiosity and composure – oh, my limpid nymphet! – for the glamorous lodger to do what he was dying to do. A modern child, an avid reader of movie magazines, an expert in dream-slow close-ups, might not think it too strange, I guessed, if a handsome, intensely virile grownup friend – too late. The house was suddenly vibrating with voluble Louise’s voice telling Mrs. Haze who had just come home about a dead something she and Leslie Tomson had found in the basement, and little Lolita was not one to miss such a tale.

Sunday. Changeful, bad-tempered, cheerful, awkward, graceful with the tart grace of her coltish subteens, excruciatingly desirable from head to foot (all New England for a lady-writer’s pen!), from the black ready-made bow and bobby pins holding her hair in place to the little scar on the lower part of her neat calf (where a roller-skater kicked her in Pisky), a couple of inches above her rough white sock. Gone with her mother to the Hamiltons – a birthday party or something. Full-skirted gingham frock. Her little doves seem well formed already. Precocious pet!

Monday. Rainy morning. ‘Ces matins gris si doux…’ My white pyjamas have a lilac design on the back. I am like one of those inflated pale spiders you see in old gardens. Sitting in the middle of a luminous web and giving little jerks to this or that strand. My web is spread all over the house as I listen from my chair where I sit like a wily wizard. Is Lo in her room? Gently I tug on the silk. She is not. Just heard the toilet paper cylinder make its staccato sound as it is turned; and no footfalls has my outflung filament traced from the bathroom back to her room. Is she still brushing her teeth (the only sanitary act Lo performs with real zest)? No. The bathroom door has just slammed, so one has to feel elsewhere about the house for the beautiful warm-coloured prey. Let us have a strand of silk descend the stairs. I satisfy myself by this means that she is not in the kitchen – not banging the refrigerator door or screeching at her detested mamma (who, I suppose, is enjoying her third, cooing and subduedly mirthful, telephone conversation of the morning). Well, let us grope and hope. Ray-like, I glide in thought to the parlour and find the radio silent (and mamma still talking to Mrs. Chatfield or Mrs. Hamilton, very softly, flushed, smiling, cupping the telephone with her free hand, denying by implication that she denies those amusing rumours, rumour, roomer, whispering intimately, as she never does, the clear-cut lady, in face to face talk). So my nymphet is not in the house at all! Gone! What I thought was a prismatic weave turns out to be but an old grey cobweb, the house is empty, is dead. And then comes Lolita’s soft sweet chuckle through my half-open door, ‘Don’t tell Mother but I’ve eaten all your bacon.’ Gone when I scuttle out of my room. Lolita, where are you? My breakfast tray, lovingly prepared by my landlady, leers at me toothlessly, ready to be taken in. Lola, Lolita!

Tuesday. Clouds again interfered with that picnic on that unattainable lake. Is it Fate scheming. Yesterday I tried on before the mirror a new pair of bathing trunks.

Wednesday. In the afternoon, Haze (common-sensical shoes, tailor-made dress), said she was driving downtown to buy a present for a friend of a friend of hers, and would I please come too because I have such a wonderful taste in textures and perfumes. ‘Choose your favourite seduction,’ she purred. What could Humbert, being in the perfume business, do? She had me cornered between the front porch and her car. ‘Hurry up,’ she said as I laboriously doubled up my large body in order to crawl in (still desperately devising a means of escape). She had started the engine, and was genteelly swearing at a backing and turning truck in front that had just brought old invalid Miss Opposite a brand new wheel chair, when my Lolita’s sharp voice came from the parlour window: ‘You! Where are you going? I’m coming too! Wait!’ ‘Ignore her,’ yelped Haze (killing the motor); alas for my fair driver; Lo was already pulling at the door on my side. ‘This is intolerable,’ began Haze; but Lo had scrambled in, shivering with glee. ‘Move your bottom, you,’ said Lo. ‘Lo!’ cried Haze (sideglancing at me, hoping I would throw rude Lo out). ‘And behold,’ said Lo (not for the first time), as she jerked back, as the car leapt forward. ‘It is intolerable,’ said Haze, violently getting into second, ‘that a child should be so ill-mannered. And so very persevering. When she knows she is unwanted. And needs a bath.’

My knuckles lay against the child’s blue jeans. She was barefooted; her toenails showed remnants of cherry-red polish and there was a bit of adhesive tape across her big toe; and, God, what would I not have given to kiss then and there those delicate-boned, long-toed, monkeyish feet! Suddenly her hand slipped into mine and without our chaperon’s seeing, I held, and stroked, and squeezed that little hot paw, all the way to the store. The wings of the driver’s Marlenesque nose shone, having shed or burned up their ration of powder, and she kept up an elegant monologue about the local traffic, and smiled in profile, and pouted in profile, and beat her painted lashes in profile, while I prayed we would never get to that store, but we did.

I have nothing else to report, save, primo: that big Haze had little Haze sit behind on our way home, and secundo: that the lady decided to keep Humbert’s Choice for the backs of her own shapely ears.

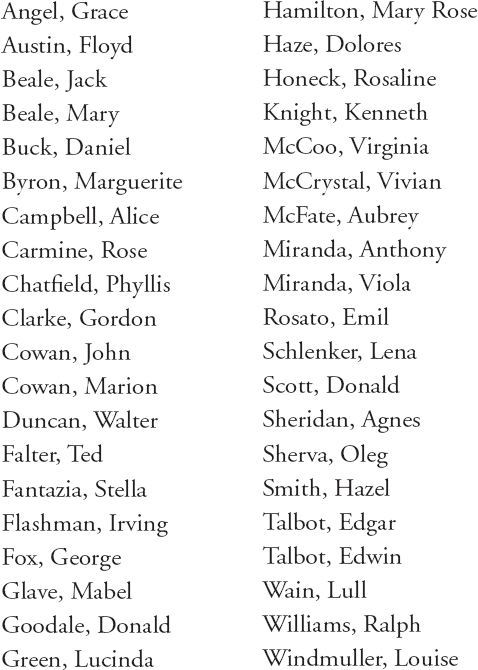

Thursday. We are paying with hail and gale for the tropical beginning of the month. In a volume of the Young People’s Encyclopaedia, I found a map of the States that a child’s pencil had started copying out on a sheet of lightweight paper, upon the other side of which, counter to the unfinished outline of Florida and the Gulf, there was a mimeographed list of names referring, evidently, to her class at the Ramsdale school. It is a poem I know already by heart.

A poem, a poem, forsooth! So strange and sweet was it to discover this ‘Haze, Dolores’ (she!) in its special bower of names, with its bodyguard of roses – a fairy princess between her two maids of honour. I am trying to analyse the spine-thrill of delight it gives me, this name among all those others. What is it that excites me almost to tears (hot, opalescent, thick tears that poets and lovers shed)? What is it? The tender anonymity of this name with its formal veil (‘Dolores’) and that abstract transposition of first name and surname, which is like a pair of new pale gloves or a mask? Is ‘mask’ the keyword? Is it because there is always delight in the semi-translucent mystery, the flowing charshaf, through which the flesh and the eye you alone are elected to know smile in passing at you alone? Or is it because I can imagine so well the rest of the colourful classroom around my dolorous and hazy darling: Grace and her ripe pimples; Ginny and her lagging leg; Gordon, the haggard masturbator; Duncan, the foul-smelling clown; nail-biting Agnes; Viola, of the blackheads and the bouncing bust; pretty Rosaline; dark Mary Rose; adorable Stella, who has let strangers touch her; Ralph, who bullies and steals; Irving, for whom I am sorry. And there she is there, lost in the middle, gnawing a pencil, detested by teachers, all the boys’ eyes on her hair and neck, my Lolita.

Friday. I long for some terrific disaster. Earthquake. Spectacular explosion. Her mother is messily but instantly and permanently eliminated, along with everybody else for miles around. Lolita whimpers in my arms. A free man, I enjoy her among the ruins. Her surprise, my explanations, demonstrations, ullulations. Idle and idiotic fancies! A brave Humbert would have played with her most disgustingly (yesterday, for instance, when she was again in my room to show me her drawings, school-artware); he might have bribed her – and got away with it. A simpler and more practical fellow would have soberly stuck to various commercial substitutes – if you know where to go, I don’t. Despite my manly looks, I am horribly timid. My romantic soul gets all clammy and shivery at the thought of running into some awful indecent unpleasantness. Those ribald sea monsters. ‘Mais allez-y, allez-y!’ Annabel skipping on one foot to get into her shorts, I seasick with rage, trying to screen her.

Same date, later, quite late. I have turned on the light to take down a dream. It had an evident antecedent. Haze at dinner had benevolently proclaimed that since the weather bureau promised a sunny weekend we would go to the lake Sunday after church. As I lay in bed, erotically musing before trying to go to sleep, I thought of a final scheme how to profit by the picnic to come. I was aware that mother Haze hated my darling for her being sweet on me. So I planned my lake day with a view to satisfying the mother. To her alone would I talk; but at some appropriate moment I would say I had left my wrist watch or my sunglasses in that glade yonder – and plunge with my nymphet into the wood. Reality at this juncture withdrew, and the Quest for the Glasses turned into a quiet little orgy with a singularly knowing, cheerful, corrupt and compliant Lolita behaving as reason knew she could not possibly behave. At 3 a.m. I swallowed a sleeping pill, and presently, a dream that was not a sequel but a parody revealed to me, with a kind of meaningful clarity, the lake I had never yet visited: it was glazed over with a sheet of emerald ice, and a pockmarked Eskimo was trying in vain to break it with a pickaxe, although imported mimosas and oleanders flowered on its gravelly banks. I am sure Dr. Blanche Schwarzmann would have paid me a sack of schillings for adding such a libidream to her files. Unfortunately, the rest of it was frankly eclectic. Big Haze and little Haze rode on horseback around the lake, and I rode too, dutifully bobbing up and down, bowlegs astraddle although there was no horse between them, only elastic air – one of those little omissions due to the absent-mindedness of the dream agent.

Saturday. My heart is still thumping. I still squirm and emit low moans of remembered embarrassment.

Dorsal view. Glimpse of shiny skin between T-shirt and white gym shorts. Bending, over a window sill, in the act of tearing off leaves from a poplar outside while engrossed in torrential talk with a newspaper boy below (Kenneth Knight, I suspect) who had just propelled the Ramsdale Journal with a very precise thud on to the porch. I began creeping up to her – ‘crippling’ up to her, as pantomimists say. My arms and legs were convex surfaces between which – rather than upon which – I slowly progressed by some neutral means of locomotion: Humbert the Wounded Spider. I must have taken hours to reach her: I seemed to see her through the wrong end of a telescope, and toward her taut little rear I moved like some paralytic, on soft distorted limbs, in terrible concentration. At last I was right behind her when I had the unfortunate idea of blustering a trifle – shaking her by the scruff of the neck and that sort of thing to cover my real manège, and she said in a shrill brief whine: ‘Cut it out!’ – most coarsely, the little wench, and with a ghastly grin Humbert the Humble beat a gloomy retreat while she went on wisecracking streetward.

But now listen to what happened next. After lunch I was reclining in a low chair trying to read. Suddenly two deft little hands were over my eyes: she had crept up behind as if re-enacting, in a ballet sequence, my morning manoeuvre. Her fingers were a luminous crimson as they tried to blot out the sun, and she uttered hiccups of laughter and jerked this way and that as I stretched my arm sideways and backwards without otherwise changing my recumbent position. My hand swept over her agile giggling legs, and the book like a sleigh left my lap, and Mrs. Haze strolled up and said indulgently: ‘Just slap her hard if she interferes with your scholarly meditations. How I love this garden [no exclamation mark in her tone]. Isn’t it divine in the sun [no question mark either].’ And with a sigh of feigned content, the obnoxious lady sank down on the grass and looked up at the sky as she leaned back on her splayed-out hands, and presently an old grey tennis ball bounced over her, and L.’s voice came from the house haughtily: ‘Pardonnez, Mother. I was not aiming at you.’ Of course not, my hot downy darling.