5. The Evidence of the Swedish Lady

M. Bouc was handling the button Mrs Hubbard had left behind her.

‘This button. I cannot understand it. Does it mean that, after all, Pierre Michel is involved in some way?’ he said. He paused, then continued, as Poirot did not reply. ‘What have you to say, my friend?’

‘That button, it suggests possibilities,’ said Poirot thoughtfully. ‘Let us interview next the Swedish lady before we discuss the evidence we have heard.’

He sorted through the pile of passports in front of him.

‘Ah! here we are. Greta Ohlsson, age forty-nine.’ M. Bouc gave directions to the restaurant attendant, and presently the lady with the yellowish-grey bun of hair and the long mild sheep-like face was ushered in. She peered short-sightedly at Poirot through her glasses, but was quite calm.

It transpired that she understood and spoke French, so that the conversation took place in that language. Poirot first asked her the questions to which he already knew the answers—her name, age, and address. He then asked her her occupation.

She was, she told him, matron in a missionary school near Stamboul. She was a trained nurse.

‘You know, of course, of what took place last night, Mademoiselle?’

‘Naturally. It is very dreadful. And the American lady tells me that the murderer was actually in her compartment.’

‘I hear, Mademoiselle, that you were the last person to see the murdered man alive?’

‘I do not know. It may be so. I opened the door of his compartment by mistake. I was much ashamed. It was a most awkward mistake.’

‘You actually saw him?’

‘Yes. He was reading a book. I apologized quickly and withdrew.’

‘Did he say anything to you?’

A slight flush showed on the worthy lady’s cheek.

‘He laughed and said a few words. I—I did not quite catch them.’

‘And what did you do after that, Mademoiselle?’ asked Poirot, passing from the subject tactfully.

‘I went in to the American lady, Mrs Hubbard. I asked her for some aspirin and she gave it to me.’

‘Did she ask you whether the communicating door between her compartment and that of M. Ratchett was bolted?’

‘Yes.’

‘And was it?’

‘Yes.’

‘And after that?’

‘After that I go back to my own compartment, I take the aspirin and lie down.’

‘What time was all this?’

‘When I got into bed it was five minutes to eleven, because I look at my watch before I wind it up.’

‘Did you go to sleep quickly?’

‘Not very quickly. My head got better, but I lay awake some time.’

‘Had the train come to a stop before you went to sleep?’

‘I do not think so. We stopped, I think, at a station, just as I was getting drowsy.’

‘That would be Vincovci. Now your compartment, Mademoiselle, is this one?’ he indicated it on the plan.

‘That is so, yes.’

‘You had the upper or the lower berth?’

‘The lower berth, No. 10.’

‘And you had a companion?’

‘Yes, a young English lady. Very nice, very amiable. She had travelled from Baghdad.’

‘After the train left Vincovci, did she leave the compartment?’

‘No, I am sure she did not.’

‘Why are you sure if you were asleep?’

‘I sleep very lightly. I am used to waking at a sound. I am sure if she had come down from the berth above I would have awakened.’

‘Did you yourself leave the compartment?’

‘Not until this morning.’

‘Have you a scarlet silk kimono, Mademoiselle?’

‘No, indeed. I have a good comfortable dressing-gown of Jaeger material.’

‘And the lady with you, Miss Debenham? What colour is her dressing-gown?’

‘A pale mauve abba such as you buy in the East.’

Poirot nodded. Then he said in a friendly tone:

‘Why are you taking this journey? A holiday?’

‘Yes, I am going home for a holiday. But first I go to Lausanne to stay with a sister for a week or so.’

‘Perhaps you will be so amiable as to write me down the name and address of your sister?’

‘With pleasure.’

She took the paper and pencil he gave her and wrote down the name and address as requested.

‘Have you ever been in America, Mademoiselle?’

‘No. Very nearly once. I was to go with an invalid lady, but it was cancelled at the last moment. I much regretted. They are very good, the Americans. They give much money to found schools and hospitals. They are very practical.’

‘Do you remember hearing of the Armstrong kidnapping case?’

‘No, what was that?’

Poirot explained.

Greta Ohlsson was indignant. Her yellow bun of hair quivered with her emotion.

‘That there are in the world such evil men! It tries one’s faith. The poor mother. My heart aches for her.’

The amiable Swede departed, her kindly face flushed, her eyes suffused with tears.

Poirot was writing busily on a sheet of paper.

‘What is it you write there, my friend?’ asked M. Bouc.

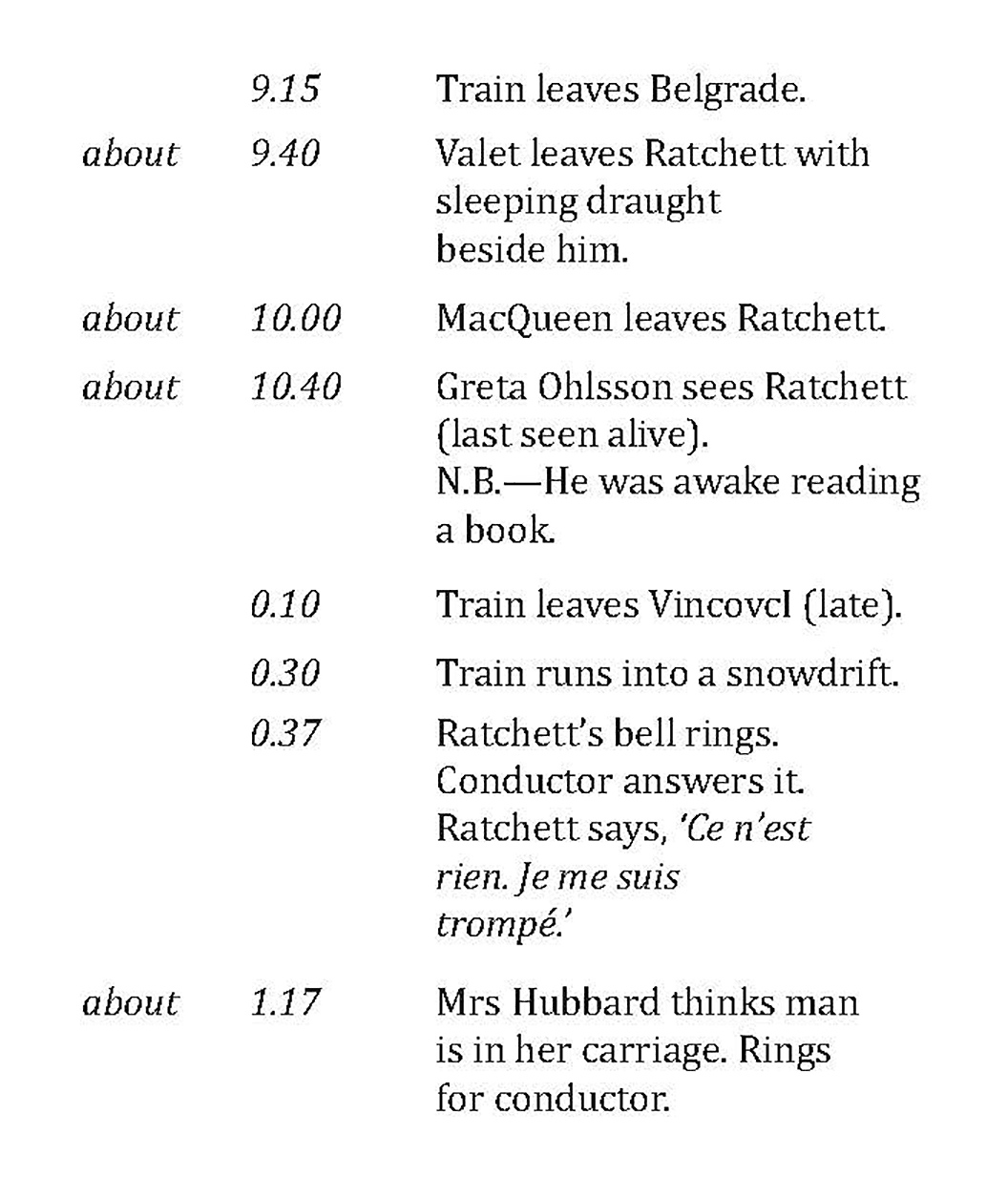

‘Mon cher, it is my habit to be neat and orderly. I make here a little table of chronological events.’

He finished writing and passed the paper to M. Bouc.

M. Bouc nodded approval.

‘That is very clear,’ he said.

‘There is nothing there that strikes you as at all odd?’

‘No, it seems all quite clear and above board. It seems quite plain that the crime was committed at 1.15. The evidence of the watch shows us that, and Mrs Hubbard’s story fits in. For my mind, I will make a guess at the identity of the murderer. I say, my friend, that it is the big Italian. He comes from America—from Chicago—and remember an Italian’s weapon is the knife, and he stabs not once but several times.’

That is true.’

‘Without a doubt, that is the solution of the mystery. Doubtless he and this Ratchett were in this kidnapping business together. CassettI is an Italian name. In some way Ratchett did on him what they call the doublecross. The Italian tracks him down, sends him warning letters first, and finally revenges himself upon him in a brutal way. It is all quite simple.’

Poirot shook his head doubtfully.

‘It is hardly as simple as that, I fear,’ he murmured.

‘Me, I am convinced it is the truth,’ said M. Bouc, becoming more and more enamoured of his theory.

‘And what about the valet with the toothache who swears that the Italian never left the compartment?’

‘That is the difficulty.’

Poirot twinkled.

‘Yes, it is annoying, that. Unlucky for your theory, and extremely lucky for our Italian friend that M. Ratchett’s valet should have had the toothache.’

‘It will be explained,’ said M. Bouc with magnificent certainty.

Poirot shook his head again.

‘No, it is hardly so simple as that,’ he murmured again.

6. The Evidence of the Russian Princess

‘Let us hear what Pierre Michel has to say about this button,’ he said.

The Wagon Lit conductor was recalled. He looked at them inquiringly.

M. Bouc cleared his throat.

‘Michel,’ he said. ‘Here is a button from your tunic. It was found in the American lady’s compartment. What have you to say for yourself about it?’

The conductor’s hand went automatically to his tunic.

‘I have lost no button, Monsieur,’ he said. ‘There must be some mistake.’

‘That is very odd.’

‘I cannot account for it, Monsieur.’

The man seemed astonished, but not in any way guilty or confused.

M. Bouc said meaningly:

‘Owing to the circumstances in which it was found, it seems fairly certain that this button was dropped by the man who was in Mrs Hubbard’s compartment last night when she rang the bell.’

‘But, Monsieur, there was no one there. The lady must have imagined it.’

‘She did not imagine it, Michael. The assassin of M. Ratchett passed that way—and dropped that button.’’

As the significance of M. Bouc’s word became plain to him, Pierre Michel flew into a violent state of agitation.

‘It is not true, Monsieur, it is not true!’ he cried. ‘You are accusing me of the crime. Me? I am innocent. I am absolutely innocent. Why should I want to kill a Monsieur whom I have never seen before?’

‘Where were you when Mrs Hubbard’s bell rang?’

‘I told you, Monsieur, in the next coach, talking to my colleague.’

‘We will send for him.’

‘Do so, Monsieur, I implore you, do so.’

The conductor of the next coach was summoned. He immediately confirmed Pierre Michel’s statement. He added that the conductor from the Bucharest coach had also been there. The three of them had been discussing the situation caused by the snow. They had been talking some ten minutes when Michel fancied he heard a bell. As he opened the doors connecting the two coaches, they had all heard it plainly. A bell ringing repeatedly. Michel had run post-haste to answer it.

‘So you see, Monsieur, I am not guilty,’ cried Michel anxiously.

‘And this button from a Wagon Lit tunic—how do you explain it?’

‘I cannot, Monsieur. It is a mystery to me. All my buttons are intact.’

Both of the other conductors also declared that they had not lost a button. Also that they had not been inside Mrs Hubbard’s compartment at any time.

‘Calm yourself, Michel,’ said M. Bouc, ‘and cast your mind back’ to the moment when you ran to answer Mrs Hubbard’s bell. Did you meet anyone at all in the corridor?’

‘No, Monsieur.’

‘Did you see anyone going away from you down the corridor in the other direction?’

‘Again, no. Monsieur.’

‘Odd,’ said M. Bouc.

‘Not so very,’ said Poirot. ‘It is a question of time. Mrs Hubbard wakes to find someone in her compartment. For a minute or two she lies paralysed, her eyes shut. Probably it was then that the man slipped out into the corridor. Then she starts ringing the bell. But the conductor does not come at once. It is only the third or fourth peal that he hears. I should say myself that there was ample time—’

‘For what? For what, mon cher? Remember that there are thick drifts of snow all round the train.’

‘There are two courses open to our mysterious assassin,’ said Poirot slowly. ‘He could retreat into either of the toilets or he could disappear into one of the compartments.’

‘But they were all occupied.’

‘Yes.’

‘You mean that he could retreat into his own compartment?’

Poirot nodded.

‘It fits, it fits,’ murmured M. Bouc. ‘During that ten minutes’ absence of the conductor, the murderer comes from his own compartment, goes into Ratchett’s, kills him, locks and chains the door on the inside, goes out through Mrs Hubbard’s compartment and is back safely in his own compartment by the time the conductor arrives.’

Poirot murmured:

‘It is not quite so simple as that, my friend. Our friend the doctor here will tell you so.’

With a gesture M. Bouc signified that the three conductors might depart.

‘We have still to see eight passengers,’ said Poirot. ‘Five first-class passengers—Princess Dragomiroff, Count and Countess Andrenyi, Colonel Arbuthnot and Mr Hardman. Three second-class passengers—Miss Debenham, Antonio FoscarellI and the lady’s-maid, Fräulein Schmidt.’

‘Who will you see first—the Italian?’

‘How you harp on your Italian! No, we will start at the top of the tree. Perhaps Madame la Princesse will be so good as to spare us a few moments of her time. Convey that message to her, Michel.’

‘Oui, Monsieur,’ said the conductor, who was just leaving the car.

‘Tell her we can wait on her in her compartment if she does not wish to put herself to the trouble of coming here,’ called M. Bouc.

But Princess Dragomiroff declined to take this course. She appeared in the dining-car, inclined her head slightly and sat down opposite Poirot.

Her small toad-like face looked even yellower than the day before. She was certainly ugly, and yet, like the toad, she had eyes like jewels, dark and imperious, revealing latent energy and an intellectual force that could be felt at once.

Her voice was deep, very distinct, with a slight grating quality in it.

She cut short a flowery phrase of apology from M. Bouc.

‘You need not offer apologies, Messieurs. I understand a murder has taken place. Naturally, you must interview all the passengers. I shall be glad to give all the assistance in my power.’

‘You are most amiable, Madame,’ said Poirot.

‘Not at all. It is a duty. What do you wish to know?’

‘Your full Christian names and address, Madame. Perhaps you would prefer to write them yourself?’

Poirot proffered a sheet of paper and pencil, but the Princess waved them aside.

‘You can write it,’ she said. ‘There is nothing difficult—Natalia Dragomiroff, 17 Avenue Kleber, Paris.’

‘You are travelling home from Constantinople, Madame?’

‘Yes, I have been staying at the Austrian Embassy. My maid is with me.’

‘Would you be so good as to give me a brief account of your movements last night from dinner onwards?’

‘Willingly. I directed the conductor to make up my bed whilst I was in the dining-car. I retired to bed immediately after dinner. I read until the hour of eleven, when I turned out my light. I was unable to sleep owing to certain rheumatic pains from which I suffer. At about a quarter to one I rang for my maid. She massaged me and then read aloud till I felt sleepy. I cannot say exactly when she left me. It may have been half an hour, it may have been later.’

‘The train had stopped then?’

‘The train had stopped.’

‘You heard nothing—nothing unusual during the time, Madame?’

‘I heard nothing unusual.’

‘What is your maid’s name?’

‘Hildegarde Schmidt.’

‘She has been with you long?’

‘Fifteen years.’

‘You consider her trustworthy?’

‘Absolutely. Her people come from an estate of my late husband’s in Germany.’

‘You have been in America, I presume, Madame?’

The abrupt change of subject made the old lady raise her eyebrows.

‘Many times.’

‘Were you at any time acquainted with a family of the name of Armstrong—a family in which a tragedy occurred?’

With some emotion in her voice the old lady said:

‘You speak of friends of mine, Monsieur.’

‘You knew Colonel Armstrong well, then?’

‘I knew him slightly; but his wife, Sonia Armstrong, was my god-daughter. I was on terms of friendship with her mother, the actress, Linda Arden. Linda Arden was a great genius, one of the greatest tragic actresses in the world. As Lady Macbeth, as Magda, there was no one to touch her.’ I was not only an admirer of her art, I was a personal friend.’

‘She is dead?’

‘No, no, she is alive, but she lives in complete retirement. Her health is very delicate, she has to lie on a sofa most of the time.’

‘There was, I think, a second daughter?’

‘Yes, much younger than Mrs Armstrong.’

‘And she is alive?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Where is she?’

The old woman bent an acute glance at him.

‘I must ask you the reason of these questions. What have they to do with the matter in hand—the murder on this train?’

‘They are connected in this way, Madame, the man who was murdered was the man responsible for the kidnapping and murder of Mrs Armstrong’s child.’

‘Ah!’

The straight brows drew together. Princess Dragomiroff drew herself a little more erect.

‘In my view, then, this murder is an entirely admirable happening! You will pardon my slightly biased point of view.’

‘It is most natural, Madame. And now to return to the question you did not answer. Where is the younger daughter of Linda Arden, the sister of Mrs Armstrong?’

‘I honestly cannot tell you, Monsieur. I have lost touch with the younger generation. I believe she married an Englishman some years ago and went to England, but at the moment I cannot recollect the name.’

She paused a minute and then said:

‘Is there anything further you want to ask me, gentlemen?’

‘Only one thing, Madame, a somewhat personal question. The colour of your dressing-gown.’

She raised her eyebrows slightly.

‘I must suppose you have a reason for such a question. My dressing-gown is of blue satin.’

‘There is nothing more, Madame. I am much obliged to you for answering my questions so promptly.’

She made a slight gesture with her heavily beringed hand’.

Then, as she rose, and the others rose with her, she stopped.

‘You will excuse me, Monsieur,’ she said, ‘but may I ask your name? Your face is somehow familiar to me.’

‘My name, Madame, is Hercule Poirot—at your service.’

She was silent a minute, then:

‘Hercule Poirot,’ she said. ‘Yes. I remember now. This is destiny.’

She walked away, very erect, a little stiff in her movements.

‘Voilà une grande dame,’ said M. Bouc. ‘What do you think of her, my friend?’

But Hercule Poirot merely shook his head.

‘I am wondering,’ he said, ‘what she meant by destiny.’