Chapter 13

He passed out of the room and began climbing the stairs. Basil Hallward followed close behind. They walked softly, as people always do at night. The lamp made strange shadows on the wall and stairs.

When they reached the top, Dorian put the lamp down on the floor. He took the key out of his pocket and turned it in the lock.

“You really want to know, Basil?” he asked in a low voice.

“Yes.”

“I am delighted,” he answered, smiling. Then he added, “You are the one man in the world I want to know everything about me. You have influenced my life more than you think.” Taking up the lamp, he opened the door and went in. Cold air passed between them. “Shut the door behind you,” he whispered, as he placed the lamp on the table.

Hallward looked around the room in surprise. The room had clearly not been lived in for years. The whole place was covered with dust, and there were holes in the carpet. A mouse ran across the floor.

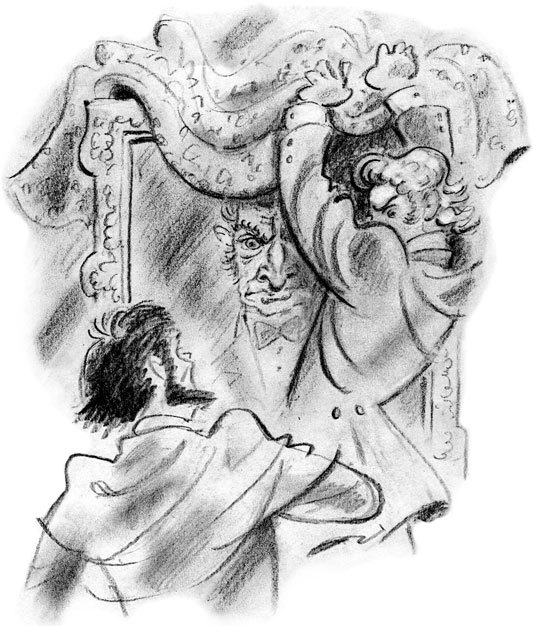

“So you think that it is only God who sees the soul, Basil.Take the cover off the portrait, and you will see mine.”

The voice that spoke was cold and cruel.

“You are mad, Dorian,” said Hallward, frowning.

“You won’t take the cover off? Then I will do it myself,” said the young man, throwing the old purple curtain to the ground.

An exclamation of horror came from the painter’s lips when he saw the face in the portrait. It was Dorian Gray’s face he was looking at, and it still had some of that wonderful beauty. But now there were terrible signs of age and corruption. Yes, it was Dorian himself. But who had done it? He held the lamp up to the picture. In the left-hand corner was his own name, painted in red.

He had never done that. Still, it was his own picture. He knew it, and it made his blood turn to ice. His own picture! What did it mean? Why had it changed? He turned, and looked at Dorian Gray with the eyes of a sick man.

The young man was standing near the wall, watching him. He had taken the flower out of his coat, and was smelling it.

“What does this mean?” cried Hallward, at last. His own voice sounded high and strange.

“Years ago, when I was a boy,” said Dorian Gray, closing his hand on the flower, “you met me and flattered me. You taught me to love my beauty. One day you introduced me to a friend of yours. He explained to me how wonderful it was to be young. You finished a portrait of me that showed me how wonderful it was to be beautiful. In a mad moment I made a wish —”

“I remember it! Oh, how well I remember it! No! The thing is impossible. There must be something wrong with the paint. I tell you the thing is impossible.”

“Is anything really impossible?” said the young man, going over to the window.

“You told me you had destroyed it.”

“I was wrong. It has destroyed me.”

“Can’t you see your ideal in it?” said Dorian bitterly.

“My ideal, as you call it…”

“As you called it.”

“There was nothing evil in it, nothing shameful. You were to me such an ideal as I shall never meet again. This is the face of a satyr.”

“It is the face of my soul.”

“Christ! what a thing I must have worshipped! It has the eyes of a devil.”

“Each of us has heaven and hell in him, Basil,” cried Dorian with a wild gesture of despair.

Hallward turned again to the portrait, and stared at it. “My God! Is this true?” he cried. “Is this what you have done with your life? You must be even worse than people say!”

Hallward threw himself into the chair by the table and put his face in his hands. The lamp fell to the floor and went out.

“Good God, Dorian! What an awful lesson! What an awful lesson!” There was no answer, but he could hear the young man crying at the window. “We must ask God for forgiveness. I worshipped you too much. I am punished for it. You worshipped yourself too much. We are both punished.”

Dorian Gray turned slowly around and looked at him. There were tears in his eyes. “It is too late, Basil,” he said.

“But don’t you see that hellish thing staring at us?”

Dorian Gray looked at the picture. Suddenly he felt that he hated Basil Hallward. He hated the man sitting at the table more than he hated anything in his life.

A flash of hatred ran through Dorian’s body. He looked at the picture and it was as if the picture told him what to do.

He looked wildly around. Something shone on top of the painted cupboard that faced him. His eye fell on it. He knew what it was. It was a knife that he had brought up, some days before, to cut a piece of cord, and had forgotten to take away with him. He moved slowly towards it, passing Hallward as he did so. He took the knife in his hand and turned around. Hallward moved in his chair. He rushed at him, and stuck the knife into his neck again and again.

He threw the knife down on the table and stood back. He could hear nothing but the sound of blood falling on to the carpet. He opened the door and went out on to the stairs. The house was completely quiet. No one was there.

How quickly it had all been done! Feeling strangely calm, he walked over to the window and opened it. The wind had blown the fog away and the sky was clear. He looked down and saw a policeman walking down the street. He was shining a lamp in all the houses.

Closing the window, he went back into the room. He did not look at the murdered man. He felt that the secret of the whole thing was not to think about it at all. The friend who had painted the terrible portrait had gone out of his life. That was enough.

He picked up the lamp and walked out of the room, locking the door behind him. As he walked down the stairs he thought that he heard what sounded like cries of pain. He stopped several times, and waited. Everything was still.

When he reached the library, he saw the bag and coat in the corner. They must be hidden away somewhere. He unlocked a secret cupboard and threw them in. He could easily burn them later. Then he pulled out his watch, it was twenty minutes to two.

He sat down and began to think. Basil Hallward had left the house at eleven. No one had seen him come in again. The servants were in bed. Paris! Yes. It was to Paris that Basil had gone. And by the midnight train as he had planned. It would be months before anyone suspected anything. Months! He could destroy everything long before then.

Suddenly he had a thought. He put on his coat and hat and went into the front room. From the window he could see the policeman passing the house. He waited, and held his breath.

Alter a few moments he went out of the house, shutting the door very gently behind him. Then he began ringing the bell. In about five minutes a servant appeared. He was half dressed and looked very sleepy.

“I am sorry I had to wake you up, Francis,” he said, stepping in. “But I have forgotten my key. What time is it?”

“Ten minutes past two, sir,” answered the man, looking at the clock and blinking.

“Ten minutes past two? How horribly late! You must wake me at nine tomorrow. I have some work to do.”

“All right, sir.”

“Did any one call this evening?”

“Mr. Hallward, sir. He stayed here till eleven, and then be went away to catch his train.”

“Oh! I am sorry I didn’t see him. Did he leave any message?”

“No, sir, except that he would write to you from Paris, if he did not find you at the club.”

“That will do, Francis. Don’t forget to call me at nine tomorrow.”

“No, sir.”

The man went off to his bedroom. Dorian Gray threw his hat and coat upon the table and passed into the library. For a quarter of an hour he walked up and down the room, biting his lip and thinking. Then he took down the Blue Book from one of the shelves and began to turn over the leaves. “Alan Campbell, 152, Hertford Street, Mayfair.” Yes; that was the man he wanted.

Chapter 14

At nine o’clock the next morning his servant came in with a cup of chocolate, and opened the curtains. Dorian was sleeping quite peacefully, lying with one hand under his cheek.

As he opened his eyes a smile passed across his lips. He turned round, and began to drink his chocolate. The November sun came into the room, and the sky was bright. It was almost like a morning in May.

Slowly he remembered what had happened the night before. The dead man was still sitting there, and in the sunlight now. How horrible that was! Such terrible things were for the darkness, not the day.

After he had drunk his cup of chocolate, he went over to the table and wrote two letters. One he put in his pocket, and the other he handed to his servant.

“Take this round to 152 Hertford Street, Francis. If Mr. Campbell is out of town, get his address.”

Alan Campbell was once a very good friend of Dorian’s. They had met at a party. Alan was a chemist but he played the piano very well, and his interest in music attracted Dorian. They went to the opera together and Alan thought, like many others, that Dorian was a wonderful man who always did exciting things. Then, one day, they stopped seeing each other. No one knew why, but they noticed that Alan always left the room when Dorian entered. Alan became sad and depressed. He stopped playing music and going to parties, and he spent most of his time alone in his laboratory doing experiments.

When the servant had gone, Dorian lit a cigarette, and began drawing on a piece of paper. First he drew flowers, then houses, then human faces. Suddenly he realized that every face he drew looked like Basil Hallward. He frowned and went over to lie on the sofa.

An hour went past very slowly. Every second he kept looking up at the clock. As the minutes went by he became horribly worried. He got up and walked around the room. His hands were strangely cold.

Dorian began to read a book. But after a time the book fell from his hand. He grew nervous. What if Alan Campbell is out of England? Perhaps he might refuse to come. What could he do then? Every moment was of vital importance.

Yes, they had been great friends once, five years before – almost inseparable, indeed. Then the intimacy had come suddenly to an end. When they met in society now, it was only Dorian Gray who smiled: Alan Campbell never did.

At last the door opened, and his servant entered.

“Mr. Campbell, sir,” said the man.

The colour came back to his cheeks.

“Ask him to come in at once, Francis.” He felt himself again. His fear had gone away.

In a few moments Alan Campbell walked in. He looked very angry and rather worried.

“Alan! This is kind of you. I thank you for coming.”

“I had intended never to enter your house again, Gray. But you said it was a matter of life and death.” His voice was hard and cold, and he kept his hands in the pockets of his coat.

“Yes, it is a question of life and death, Alan. And to more than one person. Sit down.”

Campbell took a chair by the table, and Dorian sat opposite him. The two men’s eyes met. In Dorian’s there was great sadness. He knew that what he was going to do was terrible.

After a moment of silence, Dorian said very quietly, “Alan, in a locked room at the top of the house, a dead man is sitting at a table. He has been dead for ten hours now. Don’t stir, and don’t look at me like that. Who the man is, why he died, how he died, are matters that do not concern you. What you have to do is this —”

“Stop, Gray. I don’t want to know anything more. I don’t care if what you tell me is true or not true. I don’t want any part in your life. Keep your horrible secrets to yourself. They don’t interest me any more.”

“Alan, they will have to interest you. I am awfully sorry for you, Alan, but I can’t help myself. You are the one man who can save me. Alan, you are a scientist. You know about chemistry and things of that kind. You have made experiments. What you have got to do is to destroy the thing that is upstairs. Nobody saw this person come into the house. Indeed, at the present moment he is supposed to be in Paris. You, Alan, you must change him, and everything that belongs to him, into a handful of ashes that I may scatter in the air.”

“You are mad, Dorian. I will have nothing to do with this.”

“It was suicide, Alan.”

“I am glad of that. But who drove him to it? You, I suppose.”

“Do you still refuse to do this for me?”

“Of course I refuse. You have come to the wrong man. Go to some of your friends. Don’t come to me.”

“Alan, it was murder. I killed him. You don’t know what he made me suffer.”

“Murder! Good God, Dorian, is that what you have come to? I will have nothing to do with it. Nobody ever commits a crime without doing something stupid. But I will have nothing to do with it.”

“You must have something to do with it. Wait, wait a moment; listen to me. Only listen, Alan. All I ask of you is to perform a certain scientific experiment. You go to hospitals and dead-houses, and the horrors that you do there don’t affect you. What I want you to do is merely what you have often done before.”

“I have no desire to help you. You forget that. I am simply indifferent to the whole thing. It has nothing to do with me.”

“Don’t ask any more questions, I have told you too much already. But you must do this. We were friends once, Alan.”

“Don’t speak about those days, Dorian – they are dead.”

“Alan! Alan! If you don’t help me, I am ruined. Why, they will hang me, Alan! Don’t you understand? They will hang me for what I have done. You refuse?”

“Yes.”

“I ask you, Alan.”

“It is useless.”

The same look of pity came into Dorian Gray’s eyes. Then he stretched out his hand, took a piece of paper, and wrote something on it. He read it over twice, folded it carefully, and pushed it across the table. Then he got up and went over to the window.

Campbell looked at him in surprise, and then took up the paper, and opened it. As he read it, his face became pale and he fell back in his chair. A horrible sense of sickness came over him.

After two or three minutes of terrible silence, Dorian turned round and came and stood behind him, putting his hand upon his shoulder.

“I am so sorry for you, Alan,” he murmured, “but you leave me no alternative. I have a letter written already. Here it is. You see the address. If you don’t help me, I must send it. If you don’t help me, I will send it. If I send it, you know what will happen to you. But you are going to help me. It is impossible for you to refuse now.”

Dorian showed Alan the letter he had hidden in his pocket. There was some secret in it that Alan did not want anyone to know.

Campbell put his face in his hands.

“The thing is quite simple, Alan. It has to be done. Face it, and do it.”

A terrible sound came from Campbell’s lips.

“Come, Alan, you must decide now.”

“I cannot do it,” he said, mechanically, as though words could alter things.

“You must. You have no choice. Don’t delay.”

He hesitated a moment. “Is there a fire in the room upstairs?”

“Yes, there is a gas fire.”

“I must go home and get some things from the laboratory.”

“No, Alan, you must not leave the house. Write out on a sheet of notepaper what you want and my servant will take a cab and bring the things back to you.”

Campbell wrote a few lines, and addressed an envelope to his assistant. Dorian took the note up and read it carefully. Then he rang the bell and gave it to his servant, with orders to return as soon as possible and to bring the things with him.

“Alan, you have saved my life,” said Dorian.

“Your life? Good heavens! what a life that is! You have gone from corruption to corruption, and now you have culminated in crime.”

“Ah, Alan,” murmured Dorian with a sigh, “I wish you had a thousandth part of the pity for me that I have for you.” He turned away as he spoke and stood looking out at the garden. Campbell made no answer.

It was nearly two o’clock when the servant returned with an enormous wooden box filled with the things Campbell had asked for.

Dorian looked at Campbell. “How long will your experiment take, Alan?” he said in a calm indifferent voice. The presence of a third person in the room seemed to give him extraordinary courage.

Campbell frowned and bit his lip. “It will take about five hours,” he answered.

“You can have the rest of the day to yourself, Francis.”

“Thank you, sir.”

When the servant had left, the two men carried the box up the stairs. Dorian took out the key and turned it in the lock. Then he stopped and Campbell saw that his eyes were full of tears.

“I don’t need you,” said Campbell coldly.

Dorian half opened the door. As he did so, he saw the face of the portrait staring in the sunlight. He remembered that the night before he had forgotten to cover the picture. He was about to rush forward when he saw something that made him jump back.

There was blood on one of the hands in the portrait. How horrible it was!

He hurried into the room, trying not to look at the dead man. Picking the curtain off the floor he threw it over the picture. Then he rushed out of the room and down the stairs.

It was long after seven when Campbell came back into the library. He was pale, but absolutely calm. “I have done what you asked me to do,” he muttered. “And now, good-bye. Let us never see each other again.”

“You have saved me from ruin, Alan. I cannot forget that,” said Dorian simply.

As soon as Campbell had left, he went upstairs. There was a horrible smell in the room. But the thing that had been sitting at the table was gone.