CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

ROUND ONE

Memento Mori

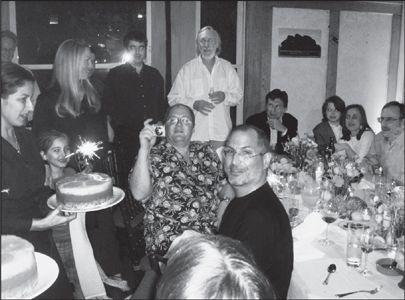

At fifty (in center), with Eve and Laurene (behind cake), Eddy Cue (by window), John Lasseter (with camera), and Lee Clow (with beard)

Cancer

Jobs would later speculate that his cancer was caused by the grueling year that he spent, starting in 1997, running both Apple and Pixar. As he drove back and forth, he had developed kidney stones and other ailments, and he would come home so exhausted that he could barely speak. “That’s probably when this cancer started growing, because my immune system was pretty weak at that time,” he said.

There is no evidence that exhaustion or a weak immune system causes cancer. However, his kidney problems did indirectly lead to the detection of his cancer. In October 2003 he happened to run into the urologist who had treated him, and she asked him to get a CAT scan of his kidneys and ureter. It had been five years since his last scan. The new scan revealed nothing wrong with his kidneys, but it did show a shadow on his pancreas, so she asked him to schedule a pancreatic study. He didn’t. As usual, he was good at willfully ignoring inputs that he did not want to process. But she persisted. “Steve, this is really important,” she said a few days later. “You need to do this.”

Her tone of voice was urgent enough that he complied. He went in early one morning, and after studying the scan, the doctors met with him to deliver the bad news that it was a tumor. One of them even suggested that he should make sure his affairs were in order, a polite way of saying that he might have only months to live. That evening they performed a biopsy by sticking an endoscope down his throat and into his intestines so they could put a needle into his pancreas and get a few cells from the tumor. Powell remembers her husband’s doctors tearing up with joy. It turned out to be an islet cell or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, which is rare but slower growing and thus more likely to be treated successfully. He was lucky that it was detected so early—as the by-product of a routine kidney screening—and thus could be surgically removed before it had definitely spread.

One of his first calls was to Larry Brilliant, whom he first met at the ashram in India. “Do you still believe in God?” Jobs asked him. Brilliant said that he did, and they discussed the many paths to God that had been taught by the Hindu guru Neem Karoli Baba. Then Brilliant asked Jobs what was wrong. “I have cancer,” Jobs replied.

Art Levinson, who was on Apple’s board, was chairing the board meeting of his own company, Genentech, when his cell phone rang and Jobs’s name appeared on the screen. As soon as there was a break, Levinson called him back and heard the news of the tumor. He had a background in cancer biology, and his firm made cancer treatment drugs, so he became an advisor. So did Andy Grove of Intel, who had fought and beaten prostate cancer. Jobs called him that Sunday, and he drove right over to Jobs’s house and stayed for two hours.

To the horror of his friends and wife, Jobs decided not to have surgery to remove the tumor, which was the only accepted medical approach. “I really didn’t want them to open up my body, so I tried to see if a few other things would work,” he told me years later with a hint of regret. Specifically, he kept to a strict vegan diet, with large quantities of fresh carrot and fruit juices. To that regimen he added acupuncture, a variety of herbal remedies, and occasionally a few other treatments he found on the Internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic. For a while he was under the sway of a doctor who operated a natural healing clinic in southern California that stressed the use of organic herbs, juice fasts, frequent bowel cleansings, hydrotherapy, and the expression of all negative feelings.

“The big thing was that he really was not ready to open his body,” Powell recalled. “It’s hard to push someone to do that.” She did try, however. “The body exists to serve the spirit,” she argued. His friends repeatedly urged him to have surgery and chemotherapy. “Steve talked to me when he was trying to cure himself by eating horseshit and horseshit roots, and I told him he was crazy,” Grove recalled. Levinson said that he “pleaded every day” with Jobs and found it “enormously frustrating that I just couldn’t connect with him.” The fights almost ruined their friendship. “That’s not how cancer works,” Levinson insisted when Jobs discussed his diet treatments. “You cannot solve this without surgery and blasting it with toxic chemicals.” Even the diet doctor Dean Ornish, a pioneer in alternative and nutritional methods of treating diseases, took a long walk with Jobs and insisted that sometimes traditional methods were the right option. “You really need surgery,” Ornish told him.

Jobs’s obstinacy lasted for nine months after his October 2003 diagnosis. Part of it was the product of the dark side of his reality distortion field. “I think Steve has such a strong desire for the world to be a certain way that he wills it to be that way,” Levinson speculated. “Sometimes it doesn’t work. Reality is unforgiving.” The flip side of his wondrous ability to focus was his fearsome willingness to filter out things he did not wish to deal with. This led to many of his great breakthroughs, but it could also backfire. “He has that ability to ignore stuff he doesn’t want to confront,” Powell explained. “It’s just the way he’s wired.” Whether it involved personal topics relating to his family and marriage, or professional issues relating to engineering or business challenges, or health and cancer issues, Jobs sometimes simply didn’t engage.

In the past he had been rewarded for what his wife called his “magical thinking”—his assumption that he could will things to be as he wanted. But cancer does not work that way. Powell enlisted everyone close to him, including his sister Mona Simpson, to try to bring him around. In July 2004 a CAT scan showed that the tumor had grown and possibly spread. It forced him to face reality.

Jobs underwent surgery on Saturday, July 31, 2004, at Stanford University Medical Center. He did not have a full “Whipple procedure,” which removes a large part of the stomach and intestine as well as the pancreas. The doctors considered it, but decided instead on a less radical approach, a modified Whipple that removed only part of the pancreas.

Jobs sent employees an email the next day, using his PowerBook hooked up to an AirPort Express in his hospital room, announcing his surgery. He assured them that the type of pancreatic cancer he had “represents about 1% of the total cases of pancreatic cancer diagnosed each year, and can be cured by surgical removal if diagnosed in time (mine was).” He said he would not require chemotherapy or radiation treatment, and he planned to return to work in September. “While I’m out, I’ve asked Tim Cook to be responsible for Apple’s day to day operations, so we shouldn’t miss a beat. I’m sure I’ll be calling some of you way too much in August, and I look forward to seeing you in September.”

One side effect of the operation would become a problem for Jobs because of his obsessive diets and the weird routines of purging and fasting that he had practiced since he was a teenager. Because the pancreas provides the enzymes that allow the stomach to digest food and absorb nutrients, removing part of the organ makes it hard to get enough protein. Patients are advised to make sure that they eat frequent meals and maintain a nutritious diet, with a wide variety of meat and fish proteins as well as full-fat milk products. Jobs had never done this, and he never would.

He stayed in the hospital for two weeks and then struggled to regain his strength. “I remember coming back and sitting in that rocking chair,” he told me, pointing to one in his living room. “I didn’t have the energy to walk. It took me a week before I could walk around the block. I pushed myself to walk to the gardens a few blocks away, then further, and within six months I had my energy almost back.”

Unfortunately the cancer had spread. During the operation the doctors found three liver metastases. Had they operated nine months earlier, they might have caught it before it spread, though they would never know for sure. Jobs began chemotherapy treatments, which further complicated his eating challenges.

The Stanford Commencement

Jobs kept his continuing battle with the cancer secret—he told everyone that he had been “cured”—just as he had kept quiet about his diagnosis in October 2003. Such secrecy was not surprising; it was part of his nature. What was more surprising was his decision to speak very personally and publicly about his cancer diagnosis. Although he rarely gave speeches other than his staged product demonstrations, he accepted Stanford’s invitation to give its June 2005 commencement address. He was in a reflective mood after his health scare and turning fifty.

For help with the speech, he called the brilliant scriptwriter Aaron Sorkin (A Few Good Men, The West Wing). Jobs sent him some thoughts. “That was in February, and I heard nothing, so I ping him again in April, and he says, ‘Oh, yeah,’ and I send him a few more thoughts,” Jobs recounted. “I finally get him on the phone, and he keeps saying ‘Yeah,’ but finally it’s the beginning of June, and he never sent me anything.”

Jobs got panicky. He had always written his own presentations, but he had never done a commencement address. One night he sat down and wrote the speech himself, with no help other than bouncing ideas off his wife. As a result, it turned out to be a very intimate and simple talk, with the unadorned and personal feel of a perfect Steve Jobs product.

Alex Haley once said that the best way to begin a speech is “Let me tell you a story.” Nobody is eager for a lecture, but everybody loves a story. And that was the approach Jobs chose. “Today, I want to tell you three stories from my life,” he began. “That’s it. No big deal. Just three stories.”

The first was about dropping out of Reed College. “I could stop taking the required classes that didn’t interest me, and begin dropping in on the ones that looked far more interesting.” The second was about how getting fired from Apple turned out to be good for him. “The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything.” The students were unusually attentive, despite a plane circling overhead with a banner that exhorted “recycle all e-waste,” and it was his third tale that enthralled them. It was about being diagnosed with cancer and the awareness it brought:

Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Because almost everything—all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure—these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.

The artful minimalism of the speech gave it simplicity, purity, and charm. Search where you will, from anthologies to YouTube, and you won’t find a better commencement address. Others may have been more important, such as George Marshall’s at Harvard in 1947 announcing a plan to rebuild Europe, but none has had more grace.

A Lion at Fifty

For his thirtieth and fortieth birthdays, Jobs had celebrated with the stars of Silicon Valley and other assorted celebrities. But when he turned fifty in 2005, after coming back from his cancer surgery, the surprise party that his wife arranged featured mainly his closest friends and professional colleagues. It was at the comfortable San Francisco home of some friends, and the great chef Alice Waters prepared salmon from Scotland along with couscous and a variety of garden-raised vegetables. “It was beautifully warm and intimate, with everyone and the kids all able to sit in one room,” Waters recalled. The entertainment was comedy improvisation done by the cast of Whose Line Is It Anyway? Jobs’s close friend Mike Slade was there, along with colleagues from Apple and Pixar, including Lasseter, Cook, Schiller, Clow, Rubinstein, and Tevanian.

Cook had done a good job running the company during Jobs’s absence. He kept Apple’s temperamental actors performing well, and he avoided stepping into the limelight. Jobs liked strong personalities, up to a point, but he had never truly empowered a deputy or shared the stage. It was hard to be his understudy. You were damned if you shone, and damned if you didn’t. Cook had managed to navigate those shoals. He was calm and decisive when in command, but he didn’t seek any notice or acclaim for himself. “Some people resent the fact that Steve gets credit for everything, but I’ve never given a rat’s ass about that,” said Cook. “Frankly speaking, I’d prefer my name never be in the paper.”

When Jobs returned from his medical leave, Cook resumed his role as the person who kept the moving parts at Apple tightly meshed and remained unfazed by Jobs’s tantrums. “What I learned about Steve was that people mistook some of his comments as ranting or negativism, but it was really just the way he showed passion. So that’s how I processed it, and I never took issues personally.” In many ways he was Jobs’s mirror image: unflappable, steady in his moods, and (as the thesaurus in the NeXT would have noted) saturnine rather than mercurial. “I’m a good negotiator, but he’s probably better than me because he’s a cool customer,” Jobs later said. After adding a bit more praise, he quietly added a reservation, one that was serious but rarely spoken: “But Tim’s not a product person, per se.”

In the fall of 2005, after returning from his medical leave, Jobs tapped Cook to become Apple’s chief operating officer. They were flying together to Japan. Jobs didn’t really ask Cook; he simply turned to him and said, “I’ve decided to make you COO.”

Around that time, Jobs’s old friends Jon Rubinstein and Avie Tevanian, the hardware and software lieutenants who had been recruited during the 1997 restoration, decided to leave. In Tevanian’s case, he had made a lot of money and was ready to quit working. “Avie is a brilliant guy and a nice guy, much more grounded than Ruby and doesn’t carry the big ego,” said Jobs. “It was a huge loss for us when Avie left. He’s a one-of-a-kind person—a genius.”

Rubinstein’s case was a little more contentious. He was upset by Cook’s ascendency and frazzled after working for nine years under Jobs. Their shouting matches became more frequent. There was also a substantive issue: Rubinstein was repeatedly clashing with Jony Ive, who used to work for him and now reported directly to Jobs. Ive was always pushing the envelope with designs that dazzled but were difficult to engineer. It was Rubinstein’s job to get the hardware built in a practical way, so he often balked. He was by nature cautious. “In the end, Ruby’s from HP,” said Jobs. “And he never delved deep, he wasn’t aggressive.”

There was, for example, the case of the screws that held the handles on the Power Mac G4. Ive decided that they should have a certain polish and shape. But Rubinstein thought that would be “astronomically” costly and delay the project for weeks, so he vetoed the idea. His job was to deliver products, which meant making trade-offs. Ive viewed that approach as inimical to innovation, so he would go both above him to Jobs and also around him to the midlevel engineers. “Ruby would say, ‘You can’t do this, it will delay,’ and I would say, ‘I think we can,’” Ive recalled. “And I would know, because I had worked behind his back with the product teams.” In this and other cases, Jobs came down on Ive’s side.

At times Ive and Rubinstein got into arguments that almost led to blows. Finally Ive told Jobs, “It’s him or me.” Jobs chose Ive. By that point Rubinstein was ready to leave. He and his wife had bought property in Mexico, and he wanted time off to build a home there. He eventually went to work for Palm, which was trying to match Apple’s iPhone. Jobs was so furious that Palm was hiring some of his former employees that he complained to Bono, who was a cofounder of a private equity group, led by the former Apple CFO Fred Anderson, that had bought a controlling stake in Palm. Bono sent Jobs a note back saying, “You should chill out about this. This is like the Beatles ringing up because Herman and the Hermits have taken one of their road crew.” Jobs later admitted that he had overreacted. “The fact that they completely failed salves that wound,” he said.

Jobs was able to build a new management team that was less contentious and a bit more subdued. Its main players, in addition to Cook and Ive, were Scott Forstall running iPhone software, Phil Schiller in charge of marketing, Bob Mansfield doing Mac hardware, Eddy Cue handling Internet services, and Peter Oppenheimer as the chief financial officer. Even though there was a surface sameness to his top team—all were middle-aged white males—there was a range of styles. Ive was emotional and expressive; Cook was as cool as steel. They all knew they were expected to be deferential to Jobs while also pushing back on his ideas and being willing to argue—a tricky balance to maintain, but each did it well. “I realized very early that if you didn’t voice your opinion, he would mow you down,” said Cook. “He takes contrary positions to create more discussion, because it may lead to a better result. So if you don’t feel comfortable disagreeing, then you’ll never survive.”

The key venue for freewheeling discourse was the Monday morning executive team gathering, which started at 9 and went for three or four hours. The focus was always on the future: What should each product do next? What new things should be developed? Jobs used the meeting to enforce a sense of shared mission at Apple. This served to centralize control, which made the company seem as tightly integrated as a good Apple product, and prevented the struggles between divisions that plagued decentralized companies.

Jobs also used the meetings to enforce focus. At Robert Friedland’s farm, his job had been to prune the apple trees so that they would stay strong, and that became a metaphor for his pruning at Apple. Instead of encouraging each group to let product lines proliferate based on marketing considerations, or permitting a thousand ideas to bloom, Jobs insisted that Apple focus on just two or three priorities at a time. “There is no one better at turning off the noise that is going on around him,” Cook said. “That allows him to focus on a few things and say no to many things. Few people are really good at that.”

In order to institutionalize the lessons that he and his team were learning, Jobs started an in-house center called Apple University. He hired Joel Podolny, who was dean of the Yale School of Management, to compile a series of case studies analyzing important decisions the company had made, including the switch to the Intel microprocessor and the decision to open the Apple Stores. Top executives spent time teaching the cases to new employees, so that the Apple style of decision making would be embedded in the culture.

In ancient Rome, when a victorious general paraded through the streets, legend has it that he was sometimes trailed by a servant whose job it was to repeat to him, “Memento mori”: Remember you will die. A reminder of mortality would help the hero keep things in perspective, instill some humility. Jobs’s memento mori had been delivered by his doctors, but it did not instill humility. Instead he roared back after his recovery with even more passion. The illness reminded him that he had nothing to lose, so he should forge ahead full speed. “He came back on a mission,” said Cook. “Even though he was now running a large company, he kept making bold moves that I don’t think anybody else would have done.”

For a while there was some evidence, or at least hope, that he had tempered his personal style, that facing cancer and turning fifty had caused him to be a bit less brutish when he was upset. “Right after he came back from his operation, he didn’t do the humiliation bit as much,” Tevanian recalled. “If he was displeased, he might scream and get hopping mad and use expletives, but he wouldn’t do it in a way that would totally destroy the person he was talking to. It was just his way to get the person to do a better job.” Tevanian reflected for a moment as he said this, then added a caveat: “Unless he thought someone was really bad and had to go, which happened every once in a while.”

Eventually, however, the rough edges returned. Because most of his colleagues were used to it by then and had learned to cope, what upset them most was when his ire turned on strangers. “Once we went to a Whole Foods market to get a smoothie,” Ive recalled. “And this older woman was making it, and he really got on her about how she was doing it. Then later, he sympathized. ‘She’s an older woman and doesn’t want to be doing this job.’ He didn’t connect the two. He was being a purist in both cases.”

On a trip to London with Jobs, Ive had the thankless task of choosing the hotel. He picked the Hempel, a tranquil five-star boutique hotel with a sophisticated minimalism that he thought Jobs would love. But as soon as they checked in, he braced himself, and sure enough his phone rang a minute later. “I hate my room,” Jobs declared. “It’s a piece of shit, let’s go.” So Ive gathered his luggage and went to the front desk, where Jobs bluntly told the shocked clerk what he thought. Ive realized that most people, himself among them, tend not to be direct when they feel something is shoddy because they want to be liked, “which is actually a vain trait.” That was an overly kind explanation. In any case, it was not a trait Jobs had.

Because Ive was so instinctively nice, he puzzled over why Jobs, whom he deeply liked, behaved as he did. One evening, in a San Francisco bar, he leaned forward with an earnest intensity and tried to analyze it:

He’s a very, very sensitive guy. That’s one of the things that makes his antisocial behavior, his rudeness, so unconscionable. I can understand why people who are thick-skinned and unfeeling can be rude, but not sensitive people. I once asked him why he gets so mad about stuff. He said, “But I don’t stay mad.” He has this very childish ability to get really worked up about something, and it doesn’t stay with him at all. But there are other times, I think honestly, when he’s very frustrated, and his way to achieve catharsis is to hurt somebody. And I think he feels he has a liberty and a license to do that. The normal rules of social engagement, he feels, don’t apply to him. Because of how very sensitive he is, he knows exactly how to efficiently and effectively hurt someone. And he does do that.

Every now and then a wise colleague would pull Jobs aside to try to get him to settle down. Lee Clow was a master. “Steve, can I talk to you?” he would quietly say when Jobs had belittled someone publicly. He would go into Jobs’s office and explain how hard everyone was working. “When you humiliate them, it’s more debilitating than stimulating,” he said in one such session. Jobs would apologize and say he understood. But then he would lapse again. “It’s simply who I am,” he would say.

One thing that did mellow was his attitude toward Bill Gates. Microsoft had kept its end of the bargain it made in 1997, when it agreed to continue developing great software for the Macintosh. Also, it was becoming less relevant as a competitor, having failed thus far to replicate Apple’s digital hub strategy. Gates and Jobs had very different approaches to products and innovation, but their rivalry had produced in each a surprising self-awareness.

For their All Things Digital conference in May 2007, the Wall Street Journal columnists Walt Mossberg and Kara Swisher worked to get them together for a joint interview. Mossberg first invited Jobs, who didn’t go to many such conferences, and was surprised when he said he would do it if Gates would. On hearing that, Gates accepted as well.

Mossberg wanted the evening joint appearance to be a cordial discussion, not a debate, but that seemed less likely when Jobs unleashed a swipe at Microsoft during a solo interview earlier that day. Asked about the fact that Apple’s iTunes software for Windows computers was extremely popular, Jobs joked, “It’s like giving a glass of ice water to somebody in hell.”

So when it was time for Gates and Jobs to meet in the green room before their joint session that evening, Mossberg was worried. Gates got there first, with his aide Larry Cohen, who had briefed him about Jobs’s remark earlier that day. When Jobs ambled in a few minutes later, he grabbed a bottle of water from the ice bucket and sat down. After a moment or two of silence, Gates said, “So I guess I’m the representative from hell.” He wasn’t smiling. Jobs paused, gave him one of his impish grins, and handed him the ice water. Gates relaxed, and the tension dissipated.

The result was a fascinating duet, in which each wunderkind of the digital age spoke warily, and then warmly, about the other. Most memorably they gave candid answers when the technology strategist Lise Buyer, who was in the audience, asked what each had learned from observing the other. “Well, I’d give a lot to have Steve’s taste,” Gates answered. There was a bit of nervous laughter; Jobs had famously said, ten years earlier, that his problem with Microsoft was that it had absolutely no taste. But Gates insisted he was serious. Jobs was a “natural in terms of intuitive taste.” He recalled how he and Jobs used to sit together reviewing the software that Microsoft was making for the Macintosh. “I’d see Steve make the decision based on a sense of people and product that, you know, is hard for me to explain. The way he does things is just different and I think it’s magical. And in that case, wow.”

Jobs stared at the floor. Later he told me that he was blown away by how honest and gracious Gates had just been. Jobs was equally honest, though not quite as gracious, when his turn came. He described the great divide between the Apple theology of building end-to-end integrated products and Microsoft’s openness to licensing its software to competing hardware makers. In the music market, the integrated approach, as manifested in his iTunes-iPod package, was proving to be the better, he noted, but Microsoft’s decoupled approach was faring better in the personal computer market. One question he raised in an offhand way was: Which approach might work better for mobile phones?

Then he went on to make an insightful point: This difference in design philosophy, he said, led him and Apple to be less good at collaborating with other companies. “Because Woz and I started the company based on doing the whole banana, we weren’t so good at partnering with people,” he said. “And I think if Apple could have had a little more of that in its DNA, it would have served it extremely well.”

Назад: CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

Дальше: CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX