CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

THE RESTORATION

The Loser Now Will Be Later to Win

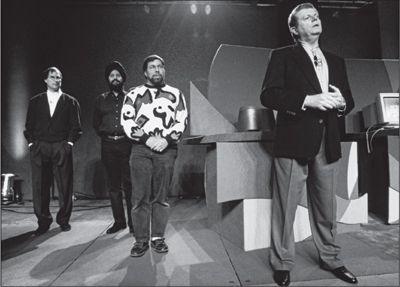

Amelio calling up Wozniak as Jobs hangs back, 1997

Hovering Backstage

“It’s rare that you see an artist in his thirties or forties able to really contribute something amazing,” Jobs declared as he was about to turn thirty.

That held true for Jobs in his thirties, during the decade that began with his ouster from Apple in 1985. But after turning forty in 1995, he flourished. Toy Story was released that year, and the following year Apple’s purchase of NeXT offered him reentry into the company he had founded. In returning to Apple, Jobs would show that even people over forty could be great innovators. Having transformed personal computers in his twenties, he would now help to do the same for music players, the recording industry’s business model, mobile phones, apps, tablet computers, books, and journalism.

He had told Larry Ellison that his return strategy was to sell NeXT to Apple, get appointed to the board, and be there ready when CEO Gil Amelio stumbled. Ellison may have been baffled when Jobs insisted that he was not motivated by money, but it was partly true. He had neither Ellison’s conspicuous consumption needs nor Gates’s philanthropic impulses nor the competitive urge to see how high on the Forbes list he could get. Instead his ego needs and personal drives led him to seek fulfillment by creating a legacy that would awe people. A dual legacy, actually: building innovative products and building a lasting company. He wanted to be in the pantheon with, indeed a notch above, people like Edwin Land, Bill Hewlett, and David Packard. And the best way to achieve all this was to return to Apple and reclaim his kingdom.

And yet when the cup of power neared his lips, he became strangely hesitant, reluctant, perhaps coy.

He returned to Apple officially in January 1997 as a part-time advisor, as he had told Amelio he would. He began to assert himself in some personnel areas, especially in protecting his people who had made the transition from NeXT. But in most other ways he was unusually passive. The decision not to ask him to join the board offended him, and he felt demeaned by the suggestion that he run the company’s operating system division. Amelio was thus able to create a situation in which Jobs was both inside the tent and outside the tent, which was not a prescription for tranquillity. Jobs later recalled:

Gil didn’t want me around. And I thought he was a bozo. I knew that before I sold him the company. I thought I was just going to be trotted out now and then for events like Macworld, mainly for show. That was fine, because I was working at Pixar. I rented an office in downtown Palo Alto where I could work a few days a week, and I drove up to Pixar for one or two days. It was a nice life. I could slow down, spend time with my family.

Jobs was, in fact, trotted out for Macworld right at the beginning of January, and this reaffirmed his opinion that Amelio was a bozo. Close to four thousand of the faithful fought for seats in the ballroom of the San Francisco Marriott to hear Amelio’s keynote address. He was introduced by the actor Jeff Goldblum. “I play an expert in chaos theory in The Lost World: Jurassic Park,” he said. “I figure that will qualify me to speak at an Apple event.” He then turned it over to Amelio, who came onstage wearing a flashy sports jacket and a banded-collar shirt buttoned tight at the neck, “looking like a Vegas comic,” the Wall Street Journal reporter Jim Carlton noted, or in the words of the technology writer Michael Malone, “looking exactly like your newly divorced uncle on his first date.”

The bigger problem was that Amelio had gone on vacation, gotten into a nasty tussle with his speechwriters, and refused to rehearse. When Jobs arrived backstage, he was upset by the chaos, and he seethed as Amelio stood on the podium bumbling through a disjointed and endless presentation. Amelio was unfamiliar with the talking points that popped up on his teleprompter and soon was trying to wing his presentation. Repeatedly he lost his train of thought. After more than an hour, the audience was aghast. There were a few welcome breaks, such as when he brought out the singer Peter Gabriel to demonstrate a new music program. He also pointed out Muhammad Ali in the first row; the champ was supposed to come onstage to promote a website about Parkinson’s disease, but Amelio never invited him up or explained why he was there.

Amelio rambled for more than two hours before he finally called onstage the person everyone was waiting to cheer. “Jobs, exuding confidence, style, and sheer magnetism, was the antithesis of the fumbling Amelio as he strode onstage,” Carlton wrote. “The return of Elvis would not have provoked a bigger sensation.” The crowd jumped to its feet and gave him a raucous ovation for more than a minute. The wilderness decade was over. Finally Jobs waved for silence and cut to the heart of the challenge. “We’ve got to get the spark back,” he said. “The Mac didn’t progress much in ten years. So Windows caught up. So we have to come up with an OS that’s even better.”

Jobs’s pep talk could have been a redeeming finale to Amelio’s frightening performance. Unfortunately Amelio came back onstage and resumed his ramblings for another hour. Finally, more than three hours after the show began, Amelio brought it to a close by calling Jobs back onstage and then, in a surprise, bringing up Steve Wozniak as well. Again there was pandemonium. But Jobs was clearly annoyed. He avoided engaging in a triumphant trio scene, arms in the air. Instead he slowly edged offstage. “He ruthlessly ruined the closing moment I had planned,” Amelio later complained. “His own feelings were more important than good press for Apple.” It was only seven days into the new year for Apple, and already it was clear that the center would not hold.

Jobs immediately put people he trusted into the top ranks at Apple. “I wanted to make sure the really good people who came in from NeXT didn’t get knifed in the back by the less competent people who were then in senior jobs at Apple,” he recalled. Ellen Hancock, who had favored choosing Sun’s Solaris over NeXT, was on the top of his bozo list, especially when she continued to want to use the kernel of Solaris in the new Apple operating system. In response to a reporter’s question about the role Jobs would play in making that decision, she answered curtly, “None.” She was wrong. Jobs’s first move was to make sure that two of his friends from NeXT took over her duties.

To head software engineering, he tapped his buddy Avie Tevanian. To run the hardware side, he called on Jon Rubinstein, who had done the same at NeXT back when it had a hardware division. Rubinstein was vacationing on the Isle of Skye when Jobs called him. “Apple needs some help,” he said. “Do you want to come aboard?” Rubinstein did. He got back in time to attend Macworld and see Amelio bomb onstage. Things were worse than he expected. He and Tevanian would exchange glances at meetings as if they had stumbled into an insane asylum, with people making deluded assertions while Amelio sat at the end of the table in a seeming stupor.

Jobs did not come into the office regularly, but he was on the phone to Amelio often. Once he had succeeded in making sure that Tevanian, Rubinstein, and others he trusted were given top positions, he turned his focus onto the sprawling product line. One of his pet peeves was Newton, the handheld personal digital assistant that boasted handwriting recognition capability. It was not quite as bad as the jokes and Doonesbury comic strip made it seem, but Jobs hated it. He disdained the idea of having a stylus or pen for writing on a screen. “God gave us ten styluses,” he would say, waving his fingers. “Let’s not invent another.” In addition, he viewed Newton as John Sculley’s one major innovation, his pet project. That alone doomed it in Jobs’s eyes.

“You ought to kill Newton,” he told Amelio one day by phone.

It was a suggestion out of the blue, and Amelio pushed back. “What do you mean, kill it?” he said. “Steve, do you have any idea how expensive that would be?”

“Shut it down, write it off, get rid of it,” said Jobs. “It doesn’t matter what it costs. People will cheer you if you got rid of it.”

“I’ve looked into Newton and it’s going to be a moneymaker,” Amelio declared. “I don’t support getting rid of it.” By May, however, he announced plans to spin off the Newton division, the beginning of its yearlong stutter-step march to the grave.

Tevanian and Rubinstein would come by Jobs’s house to keep him informed, and soon much of Silicon Valley knew that Jobs was quietly wresting power from Amelio. It was not so much a Machiavellian power play as it was Jobs being Jobs. Wanting control was ingrained in his nature. Louise Kehoe, the Financial Times reporter who had foreseen this when she questioned Jobs and Amelio at the December announcement, was the first with the story. “Mr. Jobs has become the power behind the throne,” she reported at the end of February. “He is said to be directing decisions on which parts of Apple’s operations should be cut. Mr. Jobs has urged a number of former Apple colleagues to return to the company, hinting strongly that he plans to take charge, they said. According to one of Mr. Jobs’ confidantes, he has decided that Mr. Amelio and his appointees are unlikely to succeed in reviving Apple, and he is intent upon replacing them to ensure the survival of ‘his company.’”

That month Amelio had to face the annual stockholders meeting and explain why the results for the final quarter of 1996 showed a 30% plummet in sales from the year before. Shareholders lined up at the microphones to vent their anger. Amelio was clueless about how poorly he handled the meeting. “The presentation was regarded as one of the best I had ever given,” he later wrote. But Ed Woolard, the former CEO of DuPont who was now the chair of the Apple board (Markkula had been demoted to vice chair), was appalled. “This is a disaster,” his wife whispered to him in the midst of the session. Woolard agreed. “Gil came dressed real cool, but he looked and sounded silly,” he recalled. “He couldn’t answer the questions, didn’t know what he was talking about, and didn’t inspire any confidence.”

Woolard picked up the phone and called Jobs, whom he’d never met. The pretext was to invite him to Delaware to speak to DuPont executives. Jobs declined, but as Woolard recalled, “the request was a ruse in order to talk to him about Gil.” He steered the phone call in that direction and asked Jobs point-blank what his impression of Amelio was. Woolard remembers Jobs being somewhat circumspect, saying that Amelio was not in the right job. Jobs recalled being more blunt:

I thought to myself, I either tell him the truth, that Gil is a bozo, or I lie by omission. He’s on the board of Apple, I have a duty to tell him what I think; on the other hand, if I tell him, he will tell Gil, in which case Gil will never listen to me again, and he’ll fuck the people I brought into Apple. All of this took place in my head in less than thirty seconds. I finally decided that I owed this guy the truth. I cared deeply about Apple. So I just let him have it. I said this guy is the worst CEO I’ve ever seen, I think if you needed a license to be a CEO he wouldn’t get one. When I hung up the phone, I thought, I probably just did a really stupid thing.

That spring Larry Ellison saw Amelio at a party and introduced him to the technology journalist Gina Smith, who asked how Apple was doing. “You know, Gina, Apple is like a ship,” Amelio answered. “That ship is loaded with treasure, but there’s a hole in the ship. And my job is to get everyone to row in the same direction.” Smith looked perplexed and asked, “Yeah, but what about the hole?” From then on, Ellison and Jobs joked about the parable of the ship. “When Larry relayed this story to me, we were in this sushi place, and I literally fell off my chair laughing,” Jobs recalled. “He was just such a buffoon, and he took himself so seriously. He insisted that everyone call him Dr. Amelio. That’s always a warning sign.”

Brent Schlender, Fortune’s well-sourced technology reporter, knew Jobs and was familiar with his thinking, and in March he came out with a story detailing the mess. “Apple Computer, Silicon Valley’s paragon of dysfunctional management and fumbled techno-dreams, is back in crisis mode, scrambling lugubriously in slow motion to deal with imploding sales, a floundering technology strategy, and a hemorrhaging brand name,” he wrote. “To the Machiavellian eye, it looks as if Jobs, despite the lure of Hollywood—lately he has been overseeing Pixar, maker of Toy Story and other computer-animated films—might be scheming to take over Apple.”

Once again Ellison publicly floated the idea of doing a hostile takeover and installing his “best friend” Jobs as CEO. “Steve’s the only one who can save Apple,” he told reporters. “I’m ready to help him the minute he says the word.” Like the third time the boy cried wolf, Ellison’s latest takeover musings didn’t get much notice, so later in the month he told Dan Gillmore of the San Jose Mercury News that he was forming an investor group to raise $1 billion to buy a majority stake in Apple. (The company’s market value was about $2.3 billion.) The day the story came out, Apple stock shot up 11% in heavy trading. To add to the frivolity, Ellison set up an email address, [email protected], asking the general public to vote on whether he should go ahead with it.

Jobs was somewhat amused by Ellison’s self-appointed role. “Larry brings this up now and then,” he told a reporter. “I try to explain my role at Apple is to be an advisor.” Amelio, however, was livid. He called Ellison to dress him down, but Ellison wouldn’t take the call. So Amelio called Jobs, whose response was equivocal but also partly genuine. “I really don’t understand what is going on,” he told Amelio. “I think all this is crazy.” Then he added a reassurance that was not at all genuine: “You and I have a good relationship.” Jobs could have ended the speculation by releasing a statement rejecting Ellison’s idea, but much to Amelio’s annoyance, he didn’t. He remained aloof, which served both his interests and his nature.

By then the press had turned against Amelio. Business Week ran a cover asking “Is Apple Mincemeat?”; Red Herring ran an editorial headlined “Gil Amelio, Please Resign”; and Wired ran a cover that showed the Apple logo crucified as a sacred heart with a crown of thorns and the headline “Pray.” Mike Barnicle of the Boston Globe, railing against years of Apple mismanagement, wrote, “How can these nitwits still draw a paycheck when they took the only computer that didn’t frighten people and turned it into the technological equivalent of the 1997 Red Sox bullpen?”

When Jobs and Amelio had signed the contract in February, Jobs began hopping around exuberantly and declared, “You and I need to go out and have a great bottle of wine to celebrate!” Amelio offered to bring wine from his cellar and suggested that they invite their wives. It took until June before they settled on a date, and despite the rising tensions they were able to have a good time. The food and wine were as mismatched as the diners; Amelio brought a bottle of 1964 Cheval Blanc and a Montrachet that each cost about $300; Jobs chose a vegetarian restaurant in Redwood City where the food bill totaled $72. Amelio’s wife remarked afterward, “He’s such a charmer, and his wife is too.”

Jobs could seduce and charm people at will, and he liked to do so. People such as Amelio and Sculley allowed themselves to believe that because Jobs was charming them, it meant that he liked and respected them. It was an impression that he sometimes fostered by dishing out insincere flattery to those hungry for it. But Jobs could be charming to people he hated just as easily as he could be insulting to people he liked. Amelio didn’t see this because, like Sculley, he was so eager for Jobs’s affection. Indeed the words he used to describe his yearning for a good relationship with Jobs are almost the same as those used by Sculley. “When I was wrestling with a problem, I would walk through the issue with him,” Amelio recalled. “Nine times out of ten we would agree.” Somehow he willed himself to believe that Jobs really respected him: “I was in awe over the way Steve’s mind approached problems, and had the feeling we were building a mutually trusting relationship.”

Amelio’s disillusionment came a few days after their dinner. During their negotiations, he had insisted that Jobs hold the Apple stock he got for at least six months, and preferably longer. That six months ended in June. When a block of 1.5 million shares was sold, Amelio called Jobs. “I’m telling people that the shares sold were not yours,” he said. “Remember, you and I had an understanding that you wouldn’t sell any without advising us first.”

“That’s right,” Jobs replied. Amelio took that response to mean that Jobs had not sold his shares, and he issued a statement saying so. But when the next SEC filing came out, it revealed that Jobs had indeed sold the shares. “Dammit, Steve, I asked you point-blank about these shares and you denied it was you.” Jobs told Amelio that he had sold in a “fit of depression” about where Apple was going and he didn’t want to admit it because he was “a little embarrassed.” When I asked him about it years later, he simply said, “I didn’t feel I needed to tell Gil.”

Why did Jobs mislead Amelio about selling the shares? One reason is simple: Jobs sometimes avoided the truth. Helmut Sonnenfeldt once said of Henry Kissinger, “He lies not because it’s in his interest, he lies because it’s in his nature.” It was in Jobs’s nature to mislead or be secretive when he felt it was warranted. But he also indulged in being brutally honest at times, telling the truths that most of us sugarcoat or suppress. Both the dissembling and the truth-telling were simply different aspects of his Nietzschean attitude that ordinary rules didn’t apply to him.

Exit, Pursued by a Bear

Jobs had refused to quash Larry Ellison’s takeover talk, and he had secretly sold his shares and been misleading about it. So Amelio finally became convinced that Jobs was gunning for him. “I finally absorbed the fact that I had been too willing and too eager to believe he was on my team,” Amelio recalled. “Steve’s plans to manipulate my termination were charging forward.”

Jobs was indeed bad-mouthing Amelio at every opportunity. He couldn’t help himself. But there was a more important factor in turning the board against Amelio. Fred Anderson, the chief financial officer, saw it as his fiduciary duty to keep Ed Woolard and the board informed of Apple’s dire situation. “Fred was the guy telling me that cash was draining, people were leaving, and more key players were thinking of it,” said Woolard. “He made it clear the ship was going to hit the sand soon, and even he was thinking of leaving.” That added to the worries Woolard already had from watching Amelio bumble the shareholders meeting.

At an executive session of the board in June, with Amelio out of the room, Woolard described to current directors how he calculated their odds. “If we stay with Gil as CEO, I think there’s only a 10% chance we will avoid bankruptcy,” he said. “If we fire him and convince Steve to come take over, we have a 60% chance of surviving. If we fire Gil, don’t get Steve back, and have to search for a new CEO, then we have a 40% chance of surviving.” The board gave him authority to ask Jobs to return.

Woolard and his wife flew to London, where they were planning to watch the Wimbledon tennis matches. He saw some of the tennis during the day, but spent his evenings in his suite at the Inn on the Park calling people back in America, where it was daytime. By the end of his stay, his telephone bill was $2,000.

First, he called Jobs. The board was going to fire Amelio, he said, and it wanted Jobs to come back as CEO. Jobs had been aggressive in deriding Amelio and pushing his own ideas about where to take Apple. But suddenly, when offered the cup, he became coy. “I will help,” he replied.

“As CEO?” Woolard asked.

Jobs said no. Woolard pushed hard for him to become at least the acting CEO. Again Jobs demurred. “I will be an advisor,” he said. “Unpaid.” He also agreed to become a board member—that was something he had yearned for—but declined to be the board chairman. “That’s all I can give now,” he said. After rumors began circulating, he emailed a memo to Pixar employees assuring them that he was not abandoning them. “I got a call from Apple’s board of directors three weeks ago asking me to return to Apple as their CEO,” he wrote. “I declined. They then asked me to become chairman, and I again declined. So don’t worry—the crazy rumors are just that. I have no plans to leave Pixar. You’re stuck with me.”

Why did Jobs not seize the reins? Why was he reluctant to grab the job that for two decades he had seemed to desire? When I asked him, he said:

We’d just taken Pixar public, and I was happy being CEO there. I never knew of anyone who served as CEO of two public companies, even temporarily, and I wasn’t even sure it was legal. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was enjoying spending more time with my family. I was torn. I knew Apple was a mess, so I wondered: Do I want to give up this nice lifestyle that I have? What are all the Pixar shareholders going to think? I talked to people I respected. I finally called Andy Grove at about eight one Saturday morning—too early. I gave him the pros and the cons, and in the middle he stopped me and said, “Steve, I don’t give a shit about Apple.” I was stunned. It was then I realized that I do give a shit about Apple—I started it and it is a good thing to have in the world. That was when I decided to go back on a temporary basis to help them hire a CEO.

The claim that he was enjoying spending more time with his family was not convincing. He was never destined to win a Father of the Year trophy, even when he had spare time on his hands. He was getting better at paying heed to his children, especially Reed, but his primary focus was on his work. He was frequently aloof from his two younger daughters, estranged again from Lisa, and often prickly as a husband.

So what was the real reason for his hesitancy in taking over at Apple? For all of his willfulness and insatiable desire to control things, Jobs was indecisive and reticent when he felt unsure about something. He craved perfection, and he was not always good at figuring out how to settle for something less. He did not like to wrestle with complexity or make accommodations. This was true in products, design, and furnishings for the house. It was also true when it came to personal commitments. If he knew for sure a course of action was right, he was unstoppable. But if he had doubts, he sometimes withdrew, preferring not to think about things that did not perfectly suit him. As happened when Amelio had asked him what role he wanted to play, Jobs would go silent and ignore situations that made him uncomfortable.

This attitude arose partly out of his tendency to see the world in binary terms. A person was either a hero or a bozo, a product was either amazing or shit. But he could be stymied by things that were more complex, shaded, or nuanced: getting married, buying the right sofa, committing to run a company. In addition, he didn’t want to be set up for failure. “I think Steve wanted to assess whether Apple could be saved,” Fred Anderson said.

Woolard and the board decided to go ahead and fire Amelio, even though Jobs was not yet forthcoming about how active a role he would play as an advisor. Amelio was about to go on a picnic with his wife, children, and grandchildren when the call came from Woolard in London. “We need you to step down,” Woolard said simply. Amelio replied that it was not a good time to discuss this, but Woolard felt he had to persist. “We are going to announce that we’re replacing you.”

Amelio resisted. “Remember, Ed, I told the board it was going to take three years to get this company back on its feet again,” he said. “I’m not even halfway through.”

“The board is at the place where we don’t want to discuss it further,” Woolard replied. Amelio asked who knew about the decision, and Woolard told him the truth: the rest of the board plus Jobs. “Steve was one of the people we talked to about this,” Woolard said. “His view is that you’re a really nice guy, but you don’t know much about the computer industry.”

“Why in the world would you involve Steve in a decision like this?” Amelio replied, getting angry. “Steve is not even a member of the board of directors, so what the hell is he doing in any of this conversation?” But Woolard didn’t back down, and Amelio hung up to carry on with the family picnic before telling his wife.

At times Jobs displayed a strange mixture of prickliness and neediness. He usually didn’t care one iota what people thought of him; he could cut people off and never care to speak to them again. Yet sometimes he also felt a compulsion to explain himself. So that evening Amelio received, to his surprise, a phone call from Jobs. “Gee, Gil, I just wanted you to know, I talked to Ed today about this thing and I really feel bad about it,” he said. “I want you to know that I had absolutely nothing to do with this turn of events, it was a decision the board made, but they had asked me for advice and counsel.” He told Amelio he respected him for having “the highest integrity of anyone I’ve ever met,” and went on to give some unsolicited advice. “Take six months off,” Jobs told him. “When I got thrown out of Apple, I immediately went back to work, and I regretted it.” He offered to be a sounding board if Amelio ever wanted more advice.

Amelio was stunned but managed to mumble a few words of thanks. He turned to his wife and recounted what Jobs said. “In ways, I still like the man, but I don’t believe him,” he told her.

“I was totally taken in by Steve,” she said, “and I really feel like an idiot.”

“Join the crowd,” her husband replied.

Steve Wozniak, who was himself now an informal advisor to the company, was thrilled that Jobs was coming back. (He forgave easily.) “It was just what we needed,” he said, “because whatever you think of Steve, he knows how to get the magic back.” Nor did Jobs’s triumph over Amelio surprise him. As he told Wired shortly after it happened, “Gil Amelio meets Steve Jobs, game over.”

That Monday Apple’s top employees were summoned to the auditorium. Amelio came in looking calm and relaxed. “Well, I’m sad to report that it’s time for me to move on,” he said. Fred Anderson, who had agreed to be interim CEO, spoke next, and he made it clear that he would be taking his cues from Jobs. Then, exactly twelve years since he had lost power in a July 4 weekend struggle, Jobs walked back onstage at Apple.

It immediately became clear that, whether or not he wanted to admit it publicly (or even to himself), Jobs was going to take control and not be a mere advisor. As soon as he came onstage that day—wearing shorts, sneakers, and a black turtleneck—he got to work reinvigorating his beloved institution. “Okay, tell me what’s wrong with this place,” he said. There were some murmurings, but Jobs cut them off. “It’s the products!” he answered. “So what’s wrong with the products?” Again there were a few attempts at an answer, until Jobs broke in to hand down the correct answer. “The products suck!” he shouted. “There’s no sex in them anymore!”

Woolard was able to coax Jobs to agree that his role as an advisor would be a very active one. Jobs approved a statement saying that he had “agreed to step up my involvement with Apple for up to 90 days, helping them until they hire a new CEO.” The clever formulation that Woolard used in his statement was that Jobs was coming back “as an advisor leading the team.”

Jobs took a small office next to the boardroom on the executive floor, conspicuously eschewing Amelio’s big corner office. He got involved in all aspects of the business: product design, where to cut, supplier negotiations, and advertising agency review. He believed that he had to stop the hemorrhaging of top Apple employees, and to do so he wanted to reprice their stock options. Apple stock had dropped so low that the options had become worthless. Jobs wanted to lower the exercise price, so they would be valuable again. At the time, that was legally permissible, but it was not considered good corporate practice. On his first Thursday back at Apple, Jobs called for a telephonic board meeting and outlined the problem. The directors balked. They asked for time to do a legal and financial study of what the change would mean. “It has to be done fast,” Jobs told them. “We’re losing good people.”

Even his supporter Ed Woolard, who headed the compensation committee, objected. “At DuPont we never did such a thing,” he said.

“You brought me here to fix this thing, and people are the key,” Jobs argued. When the board proposed a study that could take two months, Jobs exploded: “Are you nuts?!?” He paused for a long moment of silence, then continued. “Guys, if you don’t want to do this, I’m not coming back on Monday. Because I’ve got thousands of key decisions to make that are far more difficult than this, and if you can’t throw your support behind this kind of decision, I will fail. So if you can’t do this, I’m out of here, and you can blame it on me, you can say, ‘Steve wasn’t up for the job.’”

The next day, after consulting with the board, Woolard called Jobs back. “We’re going to approve this,” he said. “But some of the board members don’t like it. We feel like you’ve put a gun to our head.” The options for the top team (Jobs had none) were reset at $13.25, which was the price of the stock the day Amelio was ousted.

Instead of declaring victory and thanking the board, Jobs continued to seethe at having to answer to a board he didn’t respect. “Stop the train, this isn’t going to work,” he told Woolard. “This company is in shambles, and I don’t have time to wet-nurse the board. So I need all of you to resign. Or else I’m going to resign and not come back on Monday.” The one person who could stay, he said, was Woolard.

Most members of the board were aghast. Jobs was still refusing to commit himself to coming back full-time or being anything more than an advisor, yet he felt he had the power to force them to leave. The hard truth, however, was that he did have that power over them. They could not afford for him to storm off in a fury, nor was the prospect of remaining an Apple board member very enticing by then. “After all they’d been through, most were glad to be let off,” Woolard recalled.

Once again the board acquiesced. It made only one request: Would he permit one other director to stay, in addition to Woolard? It would help the optics. Jobs assented. “They were an awful board, a terrible board,” he later said. “I agreed they could keep Ed Woolard and a guy named Gareth Chang, who turned out to be a zero. He wasn’t terrible, just a zero. Woolard, on the other hand, was one of the best board members I’ve ever seen. He was a prince, one of the most supportive and wise people I’ve ever met.”

Among those being asked to resign was Mike Markkula, who in 1976, as a young venture capitalist, had visited the Jobs garage, fallen in love with the nascent computer on the workbench, guaranteed a $250,000 line of credit, and become the third partner and one-third owner of the new company. Over the subsequent two decades, he was the one constant on the board, ushering in and out a variety of CEOs. He had supported Jobs at times but also clashed with him, most notably when he sided with Sculley in the showdowns of 1985. With Jobs returning, he knew that it was time for him to leave.

Jobs could be cutting and cold, especially toward people who crossed him, but he could also be sentimental about those who had been with him from the early days. Wozniak fell into that favored category, of course, even though they had drifted apart; so did Andy Hertzfeld and a few others from the Macintosh team. In the end, Mike Markkula did as well. “I felt deeply betrayed by him, but he was like a father and I always cared about him,” Jobs later recalled. So when the time came to ask him to resign from the Apple board, Jobs drove to Markkula’s chateau-like mansion in the Woodside hills to do it personally. As usual, he asked to take a walk, and they strolled the grounds to a redwood grove with a picnic table. “He told me he wanted a new board because he wanted to start fresh,” Markkula said. “He was worried that I might take it poorly, and he was relieved when I didn’t.”

They spent the rest of the time talking about where Apple should focus in the future. Jobs’s ambition was to build a company that would endure, and he asked Markkula what the formula for that would be. Markkula replied that lasting companies know how to reinvent themselves. Hewlett-Packard had done that repeatedly; it started as an instrument company, then became a calculator company, then a computer company. “Apple has been sidelined by Microsoft in the PC business,” Markkula said. “You’ve got to reinvent the company to do some other thing, like other consumer products or devices. You’ve got to be like a butterfly and have a metamorphosis.” Jobs didn’t say much, but he agreed.

The old board met in late July to ratify the transition. Woolard, who was as genteel as Jobs was prickly, was mildly taken aback when Jobs appeared dressed in jeans and sneakers, and he worried that Jobs might start berating the veteran board members for screwing up. But Jobs merely offered a pleasant “Hi, everyone.” They got down to the business of voting to accept the resignations, elect Jobs to the board, and empower Woolard and Jobs to find new board members.

Jobs’s first recruit was, not surprisingly, Larry Ellison. He said he would be pleased to join, but he hated attending meetings. Jobs said it would be fine if he came to only half of them. (After a while Ellison was coming to only a third of the meetings. Jobs took a picture of him that had appeared on the cover of Business Week and had it blown up to life size and pasted on a cardboard cutout to put in his chair.)

Jobs also brought in Bill Campbell, who had run marketing at Apple in the early 1980s and been caught in the middle of the Sculley-Jobs clash. Campbell had ended up sticking with Sculley, but he had grown to dislike him so much that Jobs forgave him. Now he was the CEO of Intuit and a walking buddy of Jobs. “We were sitting out in the back of his house,” recalled Campbell, who lived only five blocks from Jobs in Palo Alto, “and he said he was going back to Apple and wanted me on the board. I said, ‘Holy shit, of course I will do that.’” Campbell had been a football coach at Columbia, and his great talent, Jobs said, was to “get A performances out of B players.” At Apple, Jobs told him, he would get to work with A players.

Woolard helped bring in Jerry York, who had been the chief financial officer at Chrysler and then IBM. Others were considered and then rejected by Jobs, including Meg Whitman, who was then the manager of Hasbro’s Playskool division and had been a strategic planner at Disney. (In 1998 she became CEO of eBay, and she later ran unsuccessfully for governor of California.) Over the years Jobs would bring in some strong leaders to serve on the Apple board, including Al Gore, Eric Schmidt of Google, Art Levinson of Genentech, Mickey Drexler of the Gap and J. Crew, and Andrea Jung of Avon. But he always made sure they were loyal, sometimes loyal to a fault. Despite their stature, they seemed at times awed or intimidated by Jobs, and they were eager to keep him happy.

At one point he invited Arthur Levitt, the former SEC chairman, to become a board member. Levitt, who bought his first Macintosh in 1984 and was proudly “addicted” to Apple computers, was thrilled. He was excited to visit Cupertino, where he discussed the role with Jobs. But then Jobs read a speech Levitt had given about corporate governance, which argued that boards should play a strong and independent role, and he telephoned to withdraw the invitation. “Arthur, I don’t think you’d be happy on our board, and I think it best if we not invite you,” Levitt said Jobs told him. “Frankly, I think some of the issues you raised, while appropriate for some companies, really don’t apply to Apple’s culture.” Levitt later wrote, “I was floored. . . . It’s plain to me that Apple’s board is not designed to act independently of the CEO.”

Macworld Boston, August 1997

The staff memo announcing the repricing of Apple’s stock options was signed “Steve and the executive team,” and it soon became public that he was running all of the company’s product review meetings. These and other indications that Jobs was now deeply engaged at Apple helped push the stock up from about $13 to $20 during July. It also created a frisson of excitement as the Apple faithful gathered for the August 1997 Macworld in Boston. More than five thousand showed up hours in advance to cram into the Castle convention hall of the Park Plaza hotel for Jobs’s keynote speech. They came to see their returning hero—and to find out whether he was really ready to lead them again.

Huge cheers erupted when a picture of Jobs from 1984 was flashed on the overhead screen. “Steve! Steve! Steve!” the crowd started to chant, even as he was still being introduced. When he finally strode onstage—wearing a black vest, collarless white shirt, jeans, and an impish smile—the screams and flashbulbs rivaled those for any rock star. At first he punctured the excitement by reminding them of where he officially worked. “I’m Steve Jobs, the chairman and CEO of Pixar,” he introduced himself, flashing a slide onscreen with that title. Then he explained his role at Apple. “I, like a lot of other people, are pulling together to help Apple get healthy again.”

But as Jobs paced back and forth across the stage, changing the overhead slides with a clicker in his hand, it was clear that he was now in charge at Apple—and was likely to remain so. He delivered a carefully crafted presentation, using no notes, on why Apple’s sales had fallen by 30% over the previous two years. “There are a lot of great people at Apple, but they’re doing the wrong things because the plan has been wrong,” he said. “I’ve found people who can’t wait to fall into line behind a good strategy, but there just hasn’t been one.” The crowd again erupted in yelps, whistles, and cheers.

As he spoke, his passion poured forth with increasing intensity, and he began saying “we” and “I”—rather than “they”—when referring to what Apple would be doing. “I think you still have to think differently to buy an Apple computer,” he said. “The people who buy them do think different. They are the creative spirits in this world, and they’re out to change the world. We make tools for those kinds of people.” When he stressed the word “we” in that sentence, he cupped his hands and tapped his fingers on his chest. And then, in his final peroration, he continued to stress the word “we” as he talked about Apple’s future. “We too are going to think differently and serve the people who have been buying our products from the beginning. Because a lot of people think they’re crazy, but in that craziness we see genius.” During the prolonged standing ovation, people looked at each other in awe, and a few wiped tears from their eyes. Jobs had made it very clear that he and the “we” of Apple were one.

The Microsoft Pact

The climax of Jobs’s August 1997 Macworld appearance was a bombshell announcement, one that made the cover of both Time and Newsweek. Near the end of his speech, he paused for a sip of water and began to talk in more subdued tones. “Apple lives in an ecosystem,” he said. “It needs help from other partners. Relationships that are destructive don’t help anybody in this industry.” For dramatic effect, he paused again, and then explained: “I’d like to announce one of our first new partnerships today, a very meaningful one, and that is one with Microsoft.” The Microsoft and Apple logos appeared together on the screen as people gasped.

Apple and Microsoft had been at war for a decade over a variety of copyright and patent issues, most notably whether Microsoft had stolen the look and feel of Apple’s graphical user interface. Just as Jobs was being eased out of Apple in 1985, John Sculley had struck a surrender deal: Microsoft could license the Apple GUI for Windows 1.0, and in return it would make Excel exclusive to the Mac for up to two years. In 1988, after Microsoft came out with Windows 2.0, Apple sued. Sculley contended that the 1985 deal did not apply to Windows 2.0 and that further refinements to Windows (such as copying Bill Atkinson’s trick of “clipping” overlapping windows) had made the infringement more blatant. By 1997 Apple had lost the case and various appeals, but remnants of the litigation and threats of new suits lingered. In addition, President Clinton’s Justice Department was preparing a massive antitrust case against Microsoft. Jobs invited the lead prosecutor, Joel Klein, to Palo Alto. Don’t worry about extracting a huge remedy against Microsoft, Jobs told him over coffee. Instead simply keep them tied up in litigation. That would allow Apple the opportunity, Jobs explained, to “make an end run” around Microsoft and start offering competing products.

Under Amelio, the showdown had become explosive. Microsoft refused to commit to developing Word and Excel for future Macintosh operating systems, which could have destroyed Apple. In defense of Bill Gates, he was not simply being vindictive. It was understandable that he was reluctant to commit to developing for a future Macintosh operating system when no one, including the ever-changing leadership at Apple, seemed to know what that new operating system would be. Right after Apple bought NeXT, Amelio and Jobs flew together to visit Microsoft, but Gates had trouble figuring out which of them was in charge. A few days later he called Jobs privately. “Hey, what the fuck, am I supposed to put my applications on the NeXT OS?” Gates asked. Jobs responded by “making smart-ass remarks about Gil,” Gates recalled, and suggesting that the situation would soon be clarified.

When the leadership issue was partly resolved by Amelio’s ouster, one of Jobs’s first phone calls was to Gates. Jobs recalled:

I called up Bill and said, “I’m going to turn this thing around.” Bill always had a soft spot for Apple. We got him into the application software business. The first Microsoft apps were Excel and Word for the Mac. So I called him and said, “I need help.” Microsoft was walking over Apple’s patents. I said, “If we kept up our lawsuits, a few years from now we could win a billion-dollar patent suit. You know it, and I know it. But Apple’s not going to survive that long if we’re at war. I know that. So let’s figure out how to settle this right away. All I need is a commitment that Microsoft will keep developing for the Mac and an investment by Microsoft in Apple so it has a stake in our success.”

When I recounted to him what Jobs said, Gates agreed it was accurate. “We had a group of people who liked working on the Mac stuff, and we liked the Mac,” Gates recalled. He had been negotiating with Amelio for six months, and the proposals kept getting longer and more complicated. “So Steve comes in and says, ‘Hey, that deal is too complicated. What I want is a simple deal. I want the commitment and I want an investment.’ And so we put that together in just four weeks.”

Gates and his chief financial officer, Greg Maffei, made the trip to Palo Alto to work out the framework for a deal, and then Maffei returned alone the following Sunday to work on the details. When he arrived at Jobs’s home, Jobs grabbed two bottles of water out of the refrigerator and took Maffei for a walk around the Palo Alto neighborhood. Both men wore shorts, and Jobs walked barefoot. As they sat in front of a Baptist church, Jobs cut to the core issues. “These are the things we care about,” he said. “A commitment to make software for the Mac and an investment.”

Although the negotiations went quickly, the final details were not finished until hours before Jobs’s Macworld speech in Boston. He was rehearsing at the Park Plaza Castle when his cell phone rang. “Hi, Bill,” he said as his words echoed through the old hall. Then he walked to a corner and spoke in a soft tone so others couldn’t hear. The call lasted an hour. Finally, the remaining deal points were resolved. “Bill, thank you for your support of this company,” Jobs said as he crouched in his shorts. “I think the world’s a better place for it.”

During his Macworld keynote address, Jobs walked through the details of the Microsoft deal. At first there were groans and hisses from the faithful. Particularly galling was Jobs’s announcement that, as part of the peace pact, “Apple has decided to make Internet Explorer its default browser on the Macintosh.” The audience erupted in boos, and Jobs quickly added, “Since we believe in choice, we’re going to be shipping other Internet browsers, as well, and the user can, of course, change their default should they choose to.” There were some laughs and scattered applause. The audience was beginning to come around, especially when he announced that Microsoft would be investing $150 million in Apple and getting nonvoting shares.

But the mellower mood was shattered for a moment when Jobs made one of the few visual and public relations gaffes of his onstage career. “I happen to have a special guest with me today via satellite downlink,” he said, and suddenly Bill Gates’s face appeared on the huge screen looming over Jobs and the auditorium. There was a thin smile on Gates’s face that flirted with being a smirk. The audience gasped in horror, followed by some boos and catcalls. The scene was such a brutal echo of the 1984 Big Brother ad that you half expected (and hoped?) that an athletic woman would suddenly come running down the aisle and vaporize the screenshot with a well-thrown hammer.

But it was all for real, and Gates, unaware of the jeering, began speaking on the satellite link from Microsoft headquarters. “Some of the most exciting work that I’ve done in my career has been the work that I’ve done with Steve on the Macintosh,” he intoned in his high-pitched singsong. As he went on to tout the new version of Microsoft Office that was being made for the Macintosh, the audience quieted down and then slowly seemed to accept the new world order. Gates even was able to rouse some applause when he said that the new Mac versions of Word and Excel would be “in many ways more advanced than what we’ve done on the Windows platform.”

Jobs realized that the image of Gates looming over him and the audience was a mistake. “I wanted him to come to Boston,” Jobs later said. “That was my worst and stupidest staging event ever. It was bad because it made me look small, and Apple look small, and as if everything was in Bill’s hands.” Gates likewise was embarrassed when he saw the videotape of the event. “I didn’t know that my face was going to be blown up to looming proportions,” he said.

Jobs tried to reassure the audience with an impromptu sermon. “If we want to move forward and see Apple healthy again, we have to let go of a few things here,” he told the audience. “We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win Microsoft has to lose. . . . I think if we want Microsoft Office on the Mac, we better treat the company that puts it out with a little bit of gratitude.”

The Microsoft announcement, along with Jobs’s passionate reengagement with the company, provided a much-needed jolt for Apple. By the end of the day, its stock had skyrocketed $6.56, or 33%, to close at $26.31, twice the price of the day Amelio resigned. The one-day jump added $830 million to Apple’s stock market capitalization. The company was back from the edge of the grave.

Назад: CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

Дальше: CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE