Part One. Forest Friends

IT WAS THE SUMMER of 1994, more than six years ago now, when I first heard about Rafael Sánchez Mazas facing the firing squad. Three things had just happened: first my father had died; then my wife had left me; finally, I'd given up my literary career. I'm lying. The truth is, of those three things, the first two are factual, even exact; but not the third. In reality, my career as a writer had never actually got started, so it would have been difficult to give it up. It'd be more accurate to say I gave it up having barely begun. I'd published my first novel in 1989; like the collection of stories that appeared two years earlier, the book was received with glaring indifference, but a combination of vanity and an enthusiastic review written by a friend from those days contrived to convince me I could one day become a novelist and, to do so, should quit my job as a journalist and devote myself entirely to writing. The results of this change in lifestyle were five years of economic, physical and metaphysical anguish, three unfinished novels and a dreadful depression that knocked me back into an armchair in front of the television for two whole months. Fed up with paying the bills, including the one for my father's funeral, and watching me stare at the blank television screen and weep, my wife moved out as soon as I started to recover, and I was left with no choice but to forget my literary ambitions and ask for my old job back at the newspaper.

I'd just turned forty, but luckily — or because I'm not a good writer but nor am I a bad journalist, or, more likely, because there was no one at the paper willing to do my job for a salary as meagre as mine — they agreed. They assigned me to the culture section, which is where they put people they don't know what to do with. At first, with the undeclared aim of punishing my disloyalty — given that, for some journalists, a colleague who leaves journalism to write a novel is nothing less than a traitorthey made me do everything but get the boss's coffee from the bar on the corner, and very few colleagues refrained from indulging in sarcasm and irony at my expense. Time must have blunted the memory of my infidelity: soon I was editing the odd piece, writing articles, doing interviews. That was how, in July 1994, I ended up interviewing Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, who was giving a series of lectures at the university at the time. I knew Ferlosio was extremely reluctant to speak to journalists, but thanks to a friend (or rather a friend of that friend who'd organized Ferlosio's stay in the city), I managed to get him to agree to talk to me for a while. Calling that an interview would be going a bit far; if it was an interview, it was the weirdest one I've ever done. To begin with, Ferlosio showed up on the terrace of the Bistrot surrounded by a swarm of friends, disciples, admirers and hangers-on; this, added to an obvious lack of attention to his clothes and a physical appearance that inextricably blended the manner of a Castilian aristocrat ashamed of being one with that of an old Mongol warrior — massive head, unruly hair streaked with grey, hard, emaciated, difficult face, large nose and cheeks shadowed with incipient beard — might have suggested, to an uninformed observer, a religious guru surrounded by acolytes. Moreover, Ferlosio roundly refused to answer a single one of the questions I put to him, claiming he'd given the best answers he was capable of in his books. This doesn't mean he didn't want to talk to me; quite the contrary: as if seeking to refute his reputation for unsociability (or perhaps it's just unfounded), he was extremely cordial, and the afternoon flew by as we chatted. The problem was that if I asked him, say, about his division of literary personae into those of fate and those of character, he would contrive to answer me with a discourse on, say, the causes of the rout of the Persian fleet in the battle of Salamis; whereas when I tried to extract his opinion on, say, the pomp and ceremony of the celebrations of the five hundredth anniversary of the conquest of the Americas, he would answer me by describing, with a wealth of gesticulation and detail, say, the correct use of a jack plane. It was an exhausting tug-of-war, and it wasn't until the last beer of the evening that Ferlosio told the story of his father facing the firing squad, the story that's kept me in suspense for the last two years. I don't remember who mentioned the name Rafael Sánchez Mazas or how it came up (maybe it was one of Ferlosio's friends, maybe Ferlosio himself), but I do remember Ferlosio telling us:

'They shot him not far from here, at the Collell Sanctuary.' He looked at me. 'Have you ever been there? Me neither, but I know it's near Banyoles. It was at the end of the war. The 18th of July had caught him in Madrid, and he had to seek refuge in the Chilean Embassy, where he spent more than a year. Towards the end of '37 he escaped from the Embassy and left Madrid hidden in a truck, perhaps with the aim of getting to France. However, they arrested him in Barcelona and, when Franco's troops were about to reach the city, took him to Collell, up near the border. That's where they shot him. It was an execution by firing squad en masse, probably chaotic, because the war was already lost and the Republicans were rushing helter-skelter for the Pyrenees, so I don't think they knew they were executing one of the founders of the Falange, and a personal friend of José Antonio Primo de Rivera at that. My father always kept the trousers and sheepskin jacket he was wearing when they shot him, he showed them to me many times, they're probably still around; the trousers had holes in them, because the bullets only grazed him and he took advantage of the confusion of the moment to run and hide in the woods. From there, sheltering in a ditch, he heard the dogs barking and the shots and the soldiers' voices as they searched for him knowing they couldn't waste much time searching because Franco's troops were on their heels. At some point my father heard branches moving behind him; he turned and saw a militiaman looking at him. Then he heard a shout: "Is he there?" My father told how the soldier stared at him for a few seconds and then, without taking his eyes off him shouted, "There's nobody over here!", turned and walked away.'

Ferlosio paused, and his eyes contracted into a knowing expression of boundless mischief, like a little boy holding back his laughter.

'He spent several days hiding in the woods, living on what he could find or what they gave him at the farms. He didn't know the area, and moreover he'd broken his glasses, so he could hardly see; that's why he always said he'd never have survived if he hadn't met some lads from a nearby village — Cornellá de Terri it was called, or issome lads who protected and fed him until the Nationalists arrived. They became great friends, and when it was all over he stayed at their house for a few days. I don't think he ever saw them again, but he talked to me about them more than once. I remember he always called them by the name they'd given themselves: "the forest friends".'

That was the first time I heard the story told, and that's how I heard it. As for the interview with Ferlosio, I finally managed to salvage it, or perhaps I made it up: as far as I recall, not once did he allude to the battle of Salamis (but he did discuss the distinction between personae of character and personae of fate), nor to the exact use of a jack plane (but did expound on the pomp of the five hundredth anniversary celebrations of the discovery of America). Nor did the interview mention the firing squad at Collell or Sánchez Mazas. Of the first I knew only what I'd just heard Ferlosio tell, of the latter not much more; at that time I'd not read a single line of Sánchez Mazas, and to me he was no more than a mist-shrouded name, just one more of the many Falangist politicians and writers that the last years of Spanish history had hastily buried, as if the gravediggers feared they weren't entirely dead.

As a matter of fact, they weren't. At least not entirely. The story of the writer facing the firing squad at Collell and the circumstances surrounding it had so intrigued me, that after interviewing Ferlosio I started to feel curious about Sánchez Mazas; also about the Civil War, of which till then I'd known not much more than I did about the battle of Salamis or the exact use of the jack plane, and about the horrific stories that war produced, which till then I'd considered excuses for old men's nostalgia and fuel for the imagination of unimaginative novelists. Coincidentally (or maybe not so coincidentally), it became fashionable around that time for Spanish writers to rehabilitate Falangist writers. It had actually started earlier, in the mid-1980s, when certain refined, influential publishers released the occasional volume by some refined, forgotten Falangist, but by the time I became interested in Sánchez Mazas, in some literary circles they weren't just rehabilitating the good Falangist writers, but also the average and even the bad ones. Some ingenuous souls, including a few guardians of left-wing orthodoxy and the odd mischief-maker, declared that rehabilitating a Falangist writer was vindicating (or laying the groundwork to vindicate) Falangism itself. The truth was exactly the opposite: rehabilitating a Falangist writer was just rehabilitating a writer; or more precisely, it was vindicating themselves as writers by rehabilitating a good writer. I mean that the fashion arose, in the best cases (the worst aren't worth mentioning), from the natural need all writers have to invent their own tradition, from a certain urge to be provocative, from the problematic certainty that literature is one thing and life another and that it was therefore possible to be a good writer at the same time as being a terrible person (or a person who supports and foments terrible causes), from the conviction that we were being literarily unfair to certain Falangist writers, who, to use Andrés Trapiello's phrase, had won the war but lost literature. Be that as it may, Sánchez Mazas did not escape this collective disinterring: in 1986 his collected poetry was published for the first time; in 1995 a popular series included a new edition of his novel The New Life of Pedrito de Andia in 1996 another of his novels, Rosa Kriiger, also appeared in a new edition, having actually been out of print since 1984.1 read all those books then. I read them with interest — with pleasure even — but not enthusiasm: it didn't take me long to conclude that Sánchez Mazas was a good writer, but not a great writer, though I doubt I'd have known how to clearly explain the difference between a great and a good writer. I remember, in the months or years that followed, randomly gathering bits and pieces about Sánchez Mazas from things I read, and even coming across the odd summary and vague allusion to the episode at Collell.

Time passed. I began to forget the story. One day at the beginning of February 1999, the year of the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War, someone at the paper suggested the idea of writing a commemorative article about the tragic last days of the poet Antonio Machado who, in January 1939 (together with his mother, his brother José and some hundreds of thousands of their utterly terrified compatriots), driven by the advance of Franco's troops, fled from Barcelona to Collioure, on the other side of the French border, where he died a short time later. The episode was very well known, and I rightly thought that not a single Catalan (or non-Catalan) journalist would manage to avoid recalling it at some point during the anniversary, so I'd resigned myself to writing the standard time-honoured article when I remembered Sánchez Mazas and that his botched execution had occurred more or less at the same time as Machado's death, except on the Spanish side of the border. I then imagined that the symmetry and contrast between these two terrible events — a kind of chiasmus of history — was perhaps not coincidental and that, if I could manage to get across the substance of each within the same article, the strange parallel might perhaps endow them with new meaning. This belief took hold when, as I began to do a little research, I stumbled across the story of Manuel Machado's journey to Collioure, which he made shortly after the death of his brother Antonio. Then I started to write. The result was an article called 'An Essential Secret' Since, in its way, it's also essential to this story, I include it here:

Sixty years have passed since the death of Antonio Machado in the last days of the Civil War. Of all the stories contained in that history, one of the saddest is no doubt Machado's, because it ends badly. It has been told many times. He came to Barcelona from Valencia in April 1938, accompanied by his mother and his brother José, and stayed first in the Hotel Majestic and later in the Torre de Castaner, an old mansion on Sant Gervasi avenue. There he kept doing what he'd been doing since the beginning of the war: using his writing to defend the legitimate government of the Republic. He was old, weary and ill, and he no longer believed in Franco's defeat. He wrote 'This is the end; any day now Barcelona will fall. For the strategists, for the politicians, for the historians, it is all clear: we have lost the war. But in human terms, I am not so sure. Perhaps we have won.' Who knows if he guessed right about that last bit; without doubt he was right about the first. The night of 22 January 1939, four days before Franco's troops took Barcelona, Machado and his family left in a convoy for the French border. Other writers accompanied them on that nightmarish exodus, among them Corpus Barga and Carles Riba. They made stops in Cervia de Ter and Mas Faixat, near Figueres. Finally, the night of the 27th, after walking 600 metres through the rain, they crossed the border. They'd been obliged to leave their luggage behind and they had no money. Thanks to the help of Corpus Barga, they managed to make it to Collioure and get rooms in the Hotel Bougnol Quintana. Less than a month later the poet died; his mother survived him by three days. In the pocket of his overcoat, his brother José found a few notes; one of them was a verse, perhaps the first line of his last poem: 'These blue days, this childhood sun.'

The story doesn't end here. Shortly after the death of his brother Antonio, the poet Manuel Machado, who lived in Burgos, learned of it through the foreign press. Manuel and Antonio were not just brothers, they were intimates. The uprising of 18 July had caught Manuel in Burgos, rebel territory; Antonio, in Madrid, Republican territory. It is reasonable to assume that, had he been in Madrid, Manuel would have been loyal to the Republic; it would perhaps be idle to speculate what might have happened if Antonio had chanced to be in Burgos. The fact is, as soon as he heard the news of his brother's death, Manuel procured a safe-conduct and, after travelling for days across a Spain that had been reduced to ashes, arrived in Collioure. At the hotel he learned his mother had also died. He went to the cemetery. There, before the graves of his mother and his brother Antonio, he met his brother José. They talked. Two days later Manuel returned to Burgos.

But the story — at least the story I now want to tell — doesn't end here either. At more or less the same time that Machado died in Collioure, Rafael Sánchez Mazas faced a firing squad near the Sanctuary of Collell. Sánchez Mazas was a good writer; he was also a friend of José Antonio, and one of the founders and ideologues of the Falange. His adventures in the war are shrouded in mystery. A few years ago his son, Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, told me his version. I don't know whether or not it is strictly true; I'm just telling it as he told me. Trapped in Republican Madrid by the military uprising, Sánchez Mazas sought refuge in the Chilean Embassy. He spent most of the war there; towards the end he tried to escape hidden in the back of a truck, but they arrested him in Barcelona and, as Franco's troops approached the city, he was taken towards the border. Before crossing it they assembled a firing squad; but the bullets only grazed him, and he took advantage of the confusion to run and hide in the woods. From there he heard the voices of the militiamen pursuing him. One of them finally found him. He looked Sánchez Mazas in the eye. Then he shouted to his comrades 'There's nobody over here!', turned and walked away.

'Of all the stories in History,' wrote Jaime Gil, 'the saddest is no doubt Spain's, / because it ends badly.' Does it end badly? We'll never know who that militiaman was who spared Sánchez Mazas' life, nor what passed through his mind when he looked him in the eye; we'll never know what José and Manuel Machado said to each other before the graves of their brother Antonio and their mother. I don't know why, but sometimes I think, if we managed to unveil one of these parallel secrets, we might perhaps also touch on a much more essential secret.

I was very pleased with the article. When it was published, on 22 February 1999, exactly sixty years after Machado's death in Collioure, exactly sixty years and twenty-two days after Sánchez Mazas faced the firing squad at Collell (although the exact date of the execution I only learned later), my colleagues at the paper congratulated me. I received three letters over the following days; to my surpriseI've never been a polemical columnist, one of those names that abound in the letters to the editor, and there was nothing to suggest that events of sixty years ago could upset anyone very much — all three referred to the article. The first, which I imagined was written by a university student from the literature department, reproached me for having insinuated (something I don't think I did, or at least not entirely) in my article that, had Antonio Machado been in rebel Burgos in July of 1936, he would have taken Franco's side. The second was worse; it was written by a man old enough to have lived through the war. He accused me of 'revisionism' in unmistakable jargon, because the question in the last paragraph following the quote from Jaime Gil (Does it end badly?) suggested in a barely veiled way that Spain's story ends well, which in his judgement is completely false. 'It ends well for those who won the war,' he said. 'But badly for those of us who lost it. No one has ever even bothered to thank us for fighting for liberty. There is a monument to the war dead in every town in Spain. How many have you seen with, at the very least, the names of the fallen from both sides?' The letter finished: 'And damn the Transition! Sincerely, Mateu Recasens.'

The third letter was the most interesting. It was signed by someone called Miquel Aguirre. Aguirre was a historian and, according to what he said, had spent several years investigating what happened during the Civil War in the Banyoles region. Among other things, his letter gave details of a fact which at that moment struck me as astonishing: Sánchez Mazas hadn't been the only survivor of the Collell execution; a man named Jesus Pascual Aguilar also escaped with his life. Even more: it seemed Pascual had recounted the episode in a book called I Was Murdered by the Reds. 'I'm afraid this book is virtually unobtainable,' concluded the letter with the unmistakable petulance of the erudite. 'But if you are interested, I can place a copy at your disposal.' At the bottom of the letter Aguirre had put his address and a phone number.

I phoned the number immediately. After a few misunderstandings, from which I deduced that he worked for some sort of company or public institution, I managed to speak to Aguirre. I asked if he had information about the execution at Collell; he said yes. I asked if he was still willing to lend me Pascual's book; he said yes. I then asked if he'd like to meet for lunch; he said he lived in Banyoles, but came to Gerona every Thursday to record a radio programme.

'We could meet next Thursday,' he said.

It was Friday and, at the thought of a week's impatience, I was about to suggest we meet that very afternoon, in Banyoles.

'Okay,' I said, nevertheless. And at that moment I thought of Ferlosio with his innocent guru air and fiercely cheerful eyes, talking about his father on the terrace at the Bistrot. I asked: 'Shall we meet at the Bistrot?'

The Bistrot is a bar in the old part of the city, with a vaguely modernist feel to it, marble and wrought-iron tables, rotary fans, its balconies brimming with flowers and overlooking the flight of steps leading up to the Sant Domenech Plaza. On Thursday, long before the time I'd agreed with Aguirre, I was seated at a table in the Bistrot with a beer in my hand; around me bubbled the conversations of the professors from the literature department who usually ate there. As I flipped through a magazine I thought how, making the lunch arrangements, it hadn't occurred to either Aguirre or I, since we'd never met, that one of us should have mentioned some way of recognizing each other, and I was just starting to try to imagine what Aguirre might look like, solely from the voice I'd heard over the phone a week before, when a short, stocky, dark-haired individual wearing glasses stopped in front of my table with a red folder under his arm, his face barely visible under three-days' growth of stubble and a bad-guy goatee. For some reason I'd expected Aguirre to be a calm, professorial old man, not this extremely young individual standing before me with a hung-over (or perhaps just eccentric) look to him. Since he didn't say anything, I asked him if he were him. He said yes. Then he asked me if I were me. I said yes. We laughed. When the waitress came, Aguirre ordered rice á la cazuela and an entrecôte au roquefort; I ordered the rabbit and a salad. While we waited for the food Aguirre told me he'd recognized me from a photo on the back of one of my books, which he'd read a while ago. Recovering from the initial spasm of vanity, I remarked grudgingly: 'Oh, you were the one, were you?'

'I don't understand.'

I felt obliged to clarify: 'It was a joke.'

I was anxious to get to the point, but, as I didn't want to seem rude or overly interested, I asked him about the radio programme. Aguirre let out a nervous laugh, showing his teeth: white and uneven.

'It's supposed to be a humorous programme, but really it's just crap. I play a fascist police commissioner called Antonio Gargallo who prepares reports about the people he interrogates. The truth is I think I'm falling in love with him. Naturally, they know nothing about any of this at the Town Hall.'

'You work at Banyoles Town Hall?'

Aguirre nodded, looking half embarrassed and half sorrowful.

'Secretary to the mayor,' he said. 'More crap. The mayor's an old friend, he asked and I didn't know how to say no. But when this term finishes, I'm quitting.'

Since fairly recently, the municipal government of Banyoles had been in the hands of a team of very young members of the Catalan Republican Left, the radical nationalist party. Aguirre said:

'I don't know what you think, sir, but to me a civilized country is one where people don't have to waste their time on politics.'

I noticed the 'sir', but didn't let it bother me, and instead leapt to grasp the rope Aguirre had just thrown me, catching it in mid air: 'Just the opposite of what happened in '36.'

'Exactly.'

They brought the salad and the rice. Aguirre pointed at the red folder. 'I photocopied the Pascual book for you.'

'Do you know very much about what happened at Collell?'

'Not very much, no,' he said. 'It was a confusing episode.'

As he shovelled big forkfuls of rice into his mouth and washed them down with glasses of red wine, Aguirre told me, as if he felt he must put me in the picture, about the early days of the war in the region of Banyoles: the predictable failure of the coup d'état, the resulting revolution, the unconstrained savagery of the committees, the widespread burning of churches and massacres of the clergy.

'Even though it's not in style any more, I'm still anticlerical — but that was collective madness,' he added. 'Of course, it's easy to find explanations for it, but it's also easy to find explanations for Nazism. Some nationalist historians insinuate that the ones who burned down churches and killed priests were from elsewhere — immigrants and suchlike. It's a lie: they were from here, and three years later more than one of them cheered the arrival of Franco's troops. Of course, if you ask, nobody was there when they torched the churches. But that's another story. What pisses me off are those nationalists who still go around trying to sell the nonsense that it was a war between Castilians and Catalans, a movie with good guys and bad guys.'

'I thought you were a nationalist.'

Aguirre stopped eating.

'I'm not a nationalist,' he said. 'I'm an independentista'

'And what's the difference?'

'Nationalism is an ideology,' he explained, hardening his voice a little, as if annoyed at having to clarify the obvious. apos;Insidious in my opinion. Independence is only a possibility. Since nationalism is a belief, and beliefs aren't up for debate, you can't argue about it; you can about independence. To you, sir, it may seem reasonable or not. To me it does.'

I couldn't take it any more.

'I'd prefer you not to call me sir.'

'Sorry,' he said, smiled and went back to his meal. 'I'm used to talking to older people respectfully.'

Aguirre kept talking about the war; he went into great detail about the final days when — the municipal and Generalitat governments having been inoperative for months — a stampede-like disorder reigned in the region: roads invaded by interminable caravans of refugees, soldiers in uniform of every rank wandering the countryside, desperate and driven to theft, enormous piles of weapons and equipment left in the ditches. . Aguirre explained that at Collell, which had been used as a jail since the beginning of the war, there were close to a thousand prisoners being held at that time, and all or almost all of them came from Barcelona; they'd been moved there, ahead of the unstoppable advance of the rebel troops, because they were among the most dangerous or most involved in Franco's cause. Unlike Ferlosio, Aguirre did think the Republicans knew who they were executing, because the fifty they chose were very significant prisoners, people who were destined to occupy positions of social or political importance after the war: the provincial chief of the Falange in Barcelona, leaders of fifth-column groups, financiers, lawyers and priests, the majority of whom had been held in the checas in Barcelona and later on prison-ships like the Argentina and the Uruguay.

They brought the steak and the rabbit and took away the other plates (Aguirre's so clean it shone). I asked: 'Who gave the order?'

'What order?' Aguirre countered, eagerly surveying his enormous sirloin, with steak knife and fork at the ready, about to attack.

'To have them shot.'

Aguirre regarded me for a moment as if he'd forgotten I was there across from him. He shrugged his shoulders and took a loud, deep breath.

'I don't know,' he answered, exhaling as he cut a piece of steak. 'I think Pascual insinuates that it was someone called Monroy, a tough young guy who might have run the prison, because in Barcelona he'd also run checas and work camps; he's mentioned in other testimonies from the time. . In any case, if it was Monroy he most likely wasn't acting on his own volition, but obeying orders from the SIM.'

'The SIM?'

'The Servicio de Information Military Aguirre clarified. 'One of the few army organizations that was still fully functioning by that stage.' He stopped chewing for a second, then went back to speaking with his mouth full: 'It's a reasonable hypothesis: it was a desperate moment, and the SIM, of course, wouldn't bother with small fry. But there are others.'

'For example?'

'Líster. He was around there. My father saw him.'

'At Collell.'

'In Sant Miquel de Campmajor, very near there. My father was a child then and they'd sent him to a farm in that village for safety. He's told me many times about one day when a handful of men burst into the farm, Líster amongst them; they demanded food and a place to sleep and spent the night arguing in the dining room. For a long time I thought this story was an invention of my father's, especially when I realized the majority of old men who'd been alive then claimed to have seen Líster, an almost legendary character from the time he took command of the Fifth Regiment — but over the years I've been putting two and two together and I've come to the conclusion that it just might be true. You see,' he began, greedily soaking a piece of bread in the puddle of sauce his steak was swimming in (I thought he must've recovered from his hangover, and wondered if he wasn't enjoying the food more than the display of his knowledge of the war). Líster had just been made a colonel at the end of January '39. They'd put him in charge of the V Corps of the Army of the Ebro, or rather, what was left of the V Corps: a handful of shattered units barely putting up a fight, retreating in the direction of the French border. Líster's men were in the region for several weeks and some of them were definitely stationed at Collell. But as I was saying — have you read Líster's memoirs?'

I said I hadn't.

'Well, it's not exactly a memoir,' Aguirre went on. 'The book's called Our War, and it's pretty good, though he tells a tremendous number of lies, as in all memoirs. But the point is he writes that in February '39, on the night of the third to the morning of the fourth (or three days after the Collell execution), they held a meeting of the Politburo of the Communist Party at a farm in a nearby village, attended by, among other leaders and commissars, himself and Togliatti, who was then the Comintern delegate. If I'm not mistaken, they talked about the possibility of mounting a last-ditch resistance to the enemy in Catalonia at that meeting — but that doesn't matter: what counts is that the farm could well be the one where my father was staying as a refugee; at least the protagonists, the dates and places coincide, so. .'

Then, without realizing it, Aguirre unwittingly got me entangled in a recondite, filial digression. I remember thinking of my father at that moment, and being surprised, because it had been a long time since I'd thought of him; I didn't know why, but there was a lump in my throat, like a shadow of guilt.

'So, it was Líster who gave the order to shoot them?' I interrupted.

'It could have been,' he said, readily picking up the lost thread while scraping his plate clean. 'But it could just as easily not have been. In Our War he says it wasn't him, not him or his men. What else is he going to say? But, the fact is, I believe him — it wasn't his style, he was too obsessed with continuing by whatever means possible a war he'd already lost. Besides, half the things they attribute to Líster are pure legend, and the other half. . well, I guess they're true. But who knows? What seems beyond doubt to me is that whoever gave that order knew perfectly well who they were executing and, of course, who Sánchez Mazas was. Mmm,' he moaned, wiping up the last of the roquefort sauce with a piece of bread, 'I was so hungry! Do you want a bit more wine?'

They took the plates away (mine with abundant remains of rabbit; Aguirre's again so clean it shone). He ordered another carafe of wine, a piece of chocolate cake and coffee; I ordered coffee. I asked Aguirre what he knew about Sánchez Mazas and his stay at Collell.

'Not much,' he answered. 'His name appears a couple of times in the General Prosecution Records, but always in relation to his trial in Barcelona, when they caught him after he escaped from Madrid. Pascual also mentions him once or twice too. As far as I know the only one who might know more is Trapiello, Andrés Trapiello. The writer. He's edited Sánchez Mazas and written some really good things about him; he's always mentioning Sánchez Mazas' family in his diaries, so he must be in contact with them. I think I may even have read an account of the firing squad incident in one of his books. . It's a story that circulated extensively after the war, everyone who knew Sánchez Mazas then used to tell it, I suppose because he used to tell everyone. Did you know lots of people thought it was a lie? In fact, there still are those who think so.'

'Doesn't surprise me.'

'Why not?'

'Because it sounds like fiction.'

'All wars are full of stories that sound like fiction.'

'Yeah, but doesn't it still seem incredible that a man who's not particularly young, forty-five years old by then, and extremely short-sighted. .?'

'Well, of course. And who would have been in a pitiful state besides.'

'Exactly. Doesn't it seem incredible that a guy like that could manage to escape from such a situation?'

'But why incredible?' The arrival of the wine, cake and coffees didn't interrupt his reasoning. 'Surprising, yes. But not incredible. But you explained all that so well in your article! Remember it was a firing squad en masse. Remember the soldier who had to turn him in and didn't. And remember we're talking about Collell. Have you ever been there?'

I told him I hadn't, and Aguirre began to describe an enormous mass of stone besieged by thick pine forests on limy soil, a vast, mountainous, rough territory, scattered with isolated farms and tiny villages (Torn, Sant Miquel de Campmajor, Fares, Sant Ferriol, Mieres); during the war years numerous escape networks operated in these villages that, in exchange for money (sometimes out of friendship or even political affinities), helped potential victims of revolutionary repression to cross the border, as well as young men of military age who wanted to evade the compulsory conscription ordered by the Republic. According to Aguirre, the area was seething with runaways as well, people who couldn't afford the expenses of escape or didn't manage to make contact with the networks, and stayed under cover in the woods for months or even years.

'So it was the ideal place to hide,' he argued. 'By that point in the war the locals were used to dealing with fugitives, helping them out. Did Ferlosio tell you about the "forest friends"?'

My article finished at the moment the militiaman didn't give Sánchez Mazas away, not a word about the 'forest friends'. I choked on my coffee.

'Do you know about them?' I inquired.

'I know the son of one of them.'

'You're kidding.'

'I'm not kidding. He's called Jaume Figueras, he lives right near here. In Cornellá de Terri.'

'Ferlosio told me the lads who helped Sánchez Mazas were from Cornellá de Terri.'

Aguirre shrugged his shoulders as he picked up the last crumbs of chocolate cake with his fingers.

'You know more than I do then,' he admitted. 'Figueras just told me the gist of the story; but then I wasn't all that interested. I could give you his phone number and you can ask him yourself.'

Aguirre finished his coffee and we paid. We said goodbye on the Rambla, in front of Les Peixeteries Velles Bridge.

Aguirre said he'd call me the following day to give me Figueras' phone number and, as we shook hands, I noticed two smudges of chocolate darkening the corners of his mouth.

'What are you thinking of doing with this?' he asked.

I was verging on telling him to wipe his lips.

'With what?' I said, instead.

'With the Sánchez Mazas story.'

I wasn't thinking of doing anything with it — I was simply curious about it so I told him the truth.

'Nothing?' Aguirre looked at me with his small, nervous, intelligent eyes. 'I thought you were thinking of writing a novel.'

'I don't write novels anymore,' I said. 'Besides, it's not a novel, it's a true story.'

'So was the article,' said Aguirre. 'Did I tell you how much I liked it? I liked it because it was like a compressed tale, except with real characters and situations. . Like a true tale.'

The next day Aguirre called me and gave me Jaume Figueras' phone number. It was a mobile number. Figueras didn't answer, but his voice did, asking me to record a message, so I did: I said my name, my profession, that I knew Aguirre, that I was interested in talking to him about his father, Sánchez Mazas, and the 'forest friends'; I also left my phone number and asked him to call me.

For the next few days I anxiously awaited a call from Figueras, which didn't come. I called him again, I left another message, and went back to waiting. In the meantime I read I was Murdered by the Reds, Pascual Aguilar's book. It was a truculent reminder of the horrors experienced behind Republican lines, just another of the many that appeared in Spain when the war ended, except this one had been published in September 1981. The date, I fear, is not coincidental, for it can be read as both a sort of justification of those involved in the comic-opera coup on 23 February of that year (Pascual quotes several times a revealing phrase that José Antonio Primo de Rivera used to repeat as if it were his own: 'At the eleventh hour it has always been a squad of soldiers that has saved civilization'), and as a warning of the catastrophes to come with the imminent rise of the Socialist Party to power and the symbolic finale of the Transition; surprisingly, the book is very good. Pascual, who'd not had a single one of his 'old shirt' Falangist convictions eroded either by time or the changes that had occurred in Spain, nimbly recounts his adventures during the war, from the moment the military uprising catches him on vacation in a village in Teruel, which falls in the Republican zone, up to a few days after facing the firing squad in Collell — to which he dedicates many pages and fierce attention to detail, including the preceding and following days — when he's liberated by Franco's army, after having spent the war leading the life of a combination of the Scarlet Pimpernel and Henri de Lagardére, first as an active member and later as leader of a Barcelona fifth-column group, and having spent time locked up in the Vallmajor checa. Pascual's book was self-published; it contains several references to Sánchez Mazas, with whom Pascual spent the hours leading up to the execution. Following Aguirre's suggestion, I likewise read Trapiello, and in one of his books discovered that he too told the story of Sánchez Mazas facing the firing squad, and in almost the exact same way I'd heard Ferlosio tell it, except for the fact that, like me in my article or my true tale, he didn't mention the 'forest friends' either. The exact similarity between Trapiello's tale and mine surprised me. I thought Trapiello must have heard it from Ferlosio (or one of Sánchez Mazas' other children, or his wife) and imagined that, having been told so often by Sánchez Mazas in his house, it must have acquired for the family an almost formulaic character, like those perfect comic stories where you can't leave out a single word without spoiling the joke.

I got hold of Trapiello's phone number and called him in Madrid. As soon as I revealed the reason for my call he was very friendly and, although he said it had been years since he'd dealt with Sánchez Mazas, he seemed thrilled that someone was taking an interest in him; I suspected that he didn't consider Sánchez Mazas a good writer, but a great writer. Our conversation lasted over an hour. Trapiello assured me he knew no more about the Collell incident than what he'd written in his book and confirmed that, especially just after the war, many people recounted it.

'It used to turn up quite often in the Barcelona newspapers just after Catalonia was occupied by Franco's troops, and in those of the rest of the country, because it was one of the last outbursts of violence in the Catalan rearguard and they had to take full advantage of it for propaganda,' Trapiello explained. apos;If I'm not mistaken, Ridruejo mentions the incident in his memoirs, and so does Laín. And I must have a Montes article somewhere that also talks about it. . I imagine that for a time Sánchez Mazas went around telling everyone he came across. Obviously it's a brutal story, but, well, I don't know. . I suppose he was such a coward (and everyone knew he was such a coward) that he must have thought this tremendous episode redeemed his cowardice in some way.'

I asked him if he'd heard anything about the 'forest friends'. He said he had. I asked who had told him the story he told in his book. He said Liliana Ferlosio, Sánchez Mazas' wife, whom it seemed he'd visited frequently before her death.

'It's odd,' I remarked. 'Except for one detail, the story coincides point by point with what Ferlosio told me — as if, instead of telling it, they'd both recited it.'

'Which detail is that?'

'A minor one. In your telling (in Liliana's, that is), when he sees Sánchez Mazas the militiaman shrugs his shoulders and then he walks away. In mine (in Ferlosio's, that is), before he leaves the militiaman looks him in the eye for a few seconds.'

There was a silence. I thought the line had gone dead.

'Hello?'

'It's funny,' Trapiello reflected. 'Now that you mention it, that's true. I don't know where I got the shrug of the shoulders, it must have struck me as more dramatic, or more like Pío Baroja. I think, in fact, Liliana told me the militiaman stared him in the eye before he left. Yes. I even remember her saying one time, when she was reunited with Sánchez Mazas after the three years of separation during the war, he often used to talk to her about those eyes that had stared at him. The militiaman's eyes, I mean.'

Before we hung up we talked a bit more about Sánchez Mazas, about his poetry and his novels and articles, his difficult personality, his friendships and his family ('In that house everyone speaks badly about everyone else, and they're all right,' Trapiello told me González-Ruano used to say). As if he took it for granted that I was going to write something about Sánchez Mazas, but out of some scruple of decency didn't want to ask me what, Trapiello gave me a few names and some bibliographic leads and invited me to come and see him in Madrid, where he had manuscripts and photocopies of newspaper articles and other things by Sánchez Mazas.

I didn't visit Trapiello until several months later, but I immediately began to follow up the leads he'd provided.

That's how I discovered that, especially right after the end of the war, Sánchez Mazas had indeed told everyone who'd listen the story of his firing squad experience. Eugenio Montes, one of the most faithful friends he had (a writer like him, like him a Falangist), on 14 February 1939, just two weeks after the events at Collell, described him 'in a shepherd's jacket and bullet-ridden trousers', arriving 'almost resurrected from the other world' after three years of hiding and jail cells in the Republican zone. Sánchez Mazas and Montes had been joyfully reunited a few days earlier in Barcelona, in the office of the then National Chief of Propaganda for the rebels, the poet Dionisio Ridruejo. Many years later, in his memoirs, he still recalled the scene, just as another illustrious young Falangist hierarch of the moment, Pedro Laín Entralgo, did in his, somewhat later. The descriptions the two memoir writers give of Sánchez Mazas — whom Ridruejo knew a little, but whom Laín, later to loathe him, had never seen before — are noticeably similar, as if they'd been so impressed that memory had frozen the image in a common snapshot (or as if Laín had copied Ridruejo; or they'd both copied the same source): for them too he had a resurrected air, skinny, nervous and disconcerted, his hair cropped close and his curved nose dominating the famished face; they both also remember Sánchez Mazas telling the firing squad story in that very office, but perhaps Ridruejo didn't entirely believe him (and thus mentioned the 'rather novelistic details' with which he adorned the tale for them); and only Laín hadn't forgotten he was wearing a 'rough, dark sheepskin'.

Because, as I found out by chance and, after a few unusually simple procedures, was able to verify sitting in a cubicle of the Catalan Filmoteca archives, Sánchez Mazas in that same rough dark sheepskin and with that same resurrected air — skinny and with close-cropped hair also told his firing squad story in front of a camera, undoubtedly around the same time in February 1939 when he'd told his Falangist comrades in Ridruejo's office in Barcelona. The film — one of the few remaining of Sánchez Mazas — appeared in one of the first post-war news broadcasts, among martial images of Generalisimo Franco reviewing the Armada at Tarragona and idyllic images of Carmencita Franco playing in the garden of their residence in Burgos with a lion cub, a gift from Social Welfare. Sánchez Mazas is standing throughout, not wearing his glasses, his gaze a little lost; he speaks, however, with the aplomb of a man accustomed to doing so in public, with the pleasure of someone who enjoys the sound of his own voice, in a tone strangely ironic at first — when he alludes to the execution — and predictably exalted at the conclusion — when he alludes to the end of his odyssey — always a bit bombastic, but his words are so precise and the silences which govern them so measured, that he too at times gives the impression that instead of telling the story he's reciting it, like an actor playing his part on stage; otherwise, the story doesn't differ substantially from the one his son recounted to me. . So as I listened to him tell it, sitting on a stool in front of a video player, in a Filmoteca cubicle, I couldn't suppress a vague tremor, because I knew I was hearing one of the first versions, still rough and unpolished, of the same story Ferlosio was to tell me almost sixty years later, and I felt absolutely sure that what Sánchez Mazas had told his son (and what he'd told me) wasn't what he remembered happening, but what he remembered having told before. Also I wasn't in the least surprised that neither Montes nor Ridruejo nor Laín (supposing they even knew of his existence), nor of course Sánchez Mazas himself in that news bulletin directed at a numerous and anonymous mass of spectators relieved by the recent end of the war, mentioned the gesture of that nameless soldier who had orders to kill him and did not kill him; the fact is understandable without need to attribute forgetfulness or ingratitude to anyone: suffice to remember that the doctrine of war in Franco's Spain, as in all wars, dictated that no enemy had ever saved anyone's life: they were too busy taking them. And as for the 'forest friends'. .

A few more months passed before I managed to speak to Jaume Figueras. After leaving several messages on his mobile phone and not receiving a single reply to any of them, I had almost given up hope that he'd get in touch with me, and on occasion surmised that he must be only a figment of Aguirre's overwrought imagination or, for reasons unknown but not difficult to imagine, that Figueras simply did not welcome the idea of recalling for anyone his father's wartime adventure. What is odd (or at least it strikes me as odd now) is that in all the time since Ferlosio's tale first awoke my curiosity, it never occurred to me that any of the story's protagonists could still be alive, as if the event had happened not a mere sixty years ago, but was as remote in time as the battle of Salamis.

One day I chanced to run into Aguirre. It was in a Mexican restaurant where I'd gone to interview a nauseating novelist from Madrid who was in the city promoting his latest flatulence, which took place in Mexico; Aguirre was with a group of people, celebrating something I imagine, as I can still remember their loud, jubilant laughter and his tequila breath hitting me in the face. He came over and, nervously stroking his bad-guy goatee, asked me pointblank whether I was writing (which meant whether I was writing a book: like almost everyone, Aguirre didn't consider writing for a newspaper actual writing); a little annoyed, because nothing irritates a writer who doesn't write as much as being asked about what he's writing, I said no. He asked me what had happened with Sánchez Mazas and my true tale; even more annoyed, I said: nothing. Then he asked me if I'd spoken to Figueras. I must have been a bit drunk too, or maybe the nauseating novelist from Madrid had already got me worked up, because I said no, and petulantly added:

'If he even exists.'

'If who even exists?'

'Who do you think? Figueras.'

The comment wiped the smile off his face; he stopped stroking his goatee.

'Don't be an idiot,' he said, focusing his astonished eyes on me, and I felt a tremendous urge to slap him, though probably it was really the novelist from Madrid I wanted to slap. 'Of course he exists.'

I restrained myself.

'Then he doesn't want to talk to me.'

Almost remorseful, almost excusing himself, Aguirre explained that Figueras was a builder or contractor (or something like that) as well as a town planning advisor (or something like that) in Cornellá de Terri, that he was, in any case, a very busy person and that undoubtedly explained why he hadn't responded to my messages; then he promised he'd speak to him. When I went back to my seat I felt awful: heart and soul I despised the novelist from Madrid, who was still holding forth.

Three days later Figueras called me. He apologized for not having done so sooner (his voice sounded slow and distant on the phone, as if the man it belonged to were very elderly, perhaps unwell), he mentioned Aguirre, then asked me if I still wanted to talk to him. I said yes; but arranging a date wasn't easy. Finally, after going through every day of the week, we decided on the following week; and after going through every bar in town (beginning with the Bistrot which Figueras didn't know), we settled on the Núria, in the plaza Poeta Marquina, very close to the station.

There I was a week later, almost a quarter of an hour before the time we'd agreed. I remember the afternoon very clearly because the following day I was going on holiday to Cancún, in Mexico, with a girlfriend I'd been seeing for a while (the third since my separation: the first was a colleague from the newspaper; the second, a girl who worked at a Pans and Company sandwich shop). Her name was Conchi and her only job I knew of was that of fortune-teller on the local television station; her stage name was Jasmine. Conchi intimidated me a little, but I suspect I've always liked women who intimidate me a little, and obviously I made sure no acquaintance would surprise me with her — not so much because I was embarrassed to be seen dating a well-known fortune-teller, as for her rather flashy appearance (bleached blonde hair, leather mini-skirt, tight tops and spike heels); and also because, why lie, Conchi was a little bit special. I remember the first time I took her back to my place. While I was wrestling with the lock on the main door, she said:

'This city's fucking pathetic'

I asked her why.

'Look,' she said and, with a grimace of utter disgust, pointed to a plaque which read: 'Avinguda Lluis Pericot. Prehistorian.' 'They could've named the street after someone who'd at least finished university, don't you think?'

Conchi loved the idea of dating a journalist (an intellectual, she'd say) and, although I'm sure she never finished reading a single one of my articles (or only the odd very short one), she always pretended to read them and in the place of honour in her living room, flanking an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe raised up on a pedestal, she had a copy of each of my books exquisitely sheathed in clear plastic. 'He's my boyfriend,' I imagined her telling her semiliterate friends, feeling very superior to them, each time one stepped into her house. When I met her, Conchi had just split up with an Ecuadorian called Dos-a-Dos González, whose name, it seemed, had been chosen in honour of a football match when the team his father had supported for his entire lifetime won their national league for the first and only time. To get over Dos-a-Dos — whom she'd met at a gym, body-building, and who in good times she affectionately called Two-All and in bad ones, Brains, Brains González — Conchi had moved to Quart, a town near by, where, almost in the middle of a forest, she'd rented a great big ramshackle house very cheaply. In a subtle but insistent way, I kept telling her to move back to the city, and my insistence was based on two lines of reasoning: one explicit and another implicit, one public and another secret. The public one was that the isolated house was a danger for her, but the day two individuals attempted to break in and Conchi, who unfortunately was home at the time, ended up chasing them through the woods throwing stones at them, I had to admit that the house was a danger for anyone who tried to break into it. The secret reason was that, since I didn't have a driver's licence, every time we went from my house to Conchi's house or from Conchi's house to my house, we had to go in Conchi's Volkswagen, a wreck so old it could well merit the attention of the prehistorian Pericot and which Conchi always drove as if she might still be in time to prevent an imminent break-in at her house, and as if all the cars moving around us were occupied by an army of delinquents. So, any car journey with my girlfriend, who needless to say loved to drive, entailed a gamble I was only willing to undertake in very exceptional circumstances; these must have occurred fairly often, at least at the beginning, because I risked my neck quite a few times back then going from her house to mine or my house to hers in her Volkswagen. Moreover, although I fear I wasn't willing to admit it, I think I liked Conchi a lot (more in any case than my colleague at the newspaper and the girl from Pans and Company; less, perhaps, than my former wife); enough, in any case, that to celebrate going out together for nine months I let her convince me to spend two weeks in Cancún, a place I imagined as truly frightful, but which (I hoped) the pleasure of being with Conchi and her amazing cheerfulness would render at least tolerable. So the evening I finally managed to arrange to meet Figueras I was already packed and impatient to be off on a trip that I sometimes (but only sometimes) considered rash.

I sat down at a table in the Núria, ordered a gin and tonic and waited. It wasn't eight o'clock yet; in front of me, on the other side of the glass walls, the terrace was full of people and beyond them every once in a while a commuter train went by on the viaduct. To my left, in the park, children accompanied by their mothers played on the swings, under the sloping shadows of the plane trees. I remember I thought of Conchi, who not long before had surprised me by saying she wasn't planning to go to her grave childless, and of my former wife, who many years before had judiciously refused my suggestion that we have a child. I thought if Conchi's declaration had also been a hint (and I now think I understand that it was), then the trip to Cancún was doubly ill-advised, because I now had no intention of ever having a child; the idea of having one with Conchi struck me as laughable. For some reason I thought of my father again, and I felt guilty again. 'Soon,' I surprised myself thinking, 'when even I don't remember him, he'll be completely dead.' At that moment, as I saw a man in his sixties come into the bar, who I thought could be Figueras, I cursed myself for having arranged two meetings with strangers, in just a few months, without previously agreeing on a way to recognize each other: I stood up, asked him if he were Jaume Figueras; he said no. I went back to my table: it was almost eight-thirty. I looked around the bar for a man on his own; then I went out to the terrace, also in vain. I wondered if Figueras had been in the bar all that time, near me and, fed up with waiting, had left; I decided that it was impossible. I didn't have his mobile number with me, so, choosing to believe that for some reason Figueras was running late and was about to arrive, I opted to wait. I ordered another gin and tonic and sat down at a table on the terrace. I nervously watched the tables around me and those inside; while I was doing so, two young Gypsies came up — a man and a woman — with an electric keyboard, a microphone and a speaker, and started playing for the customers. The man played and the woman sang. They played mostly paso dobles: I remember very well because Conchi loved paso dobles so much that she'd tried unsuccessfully to get me to sign up for a course to learn how to dance them, and especially because it was the first time in my life I heard the lyrics to 'Sighing for Spain', a very famous paso doble I didn't even know had lyrics:

God desired, in his power,

to blend four little sunbeams

and make of them a woman

and when His will was done

in a Spanish garden I was born

like a flower on her rose-bush.

Glorious land of my love,

blessed land of perfume and passion,

Spain, in each flower at your feet

a heart is sighing.

Oh, I'm dying of sorrow,

for I'm going away, Spain, from you,

for away from my rose-bush I'm torn.*

Listening to the Gypsies play and sing I thought it was the saddest song in the world; also, barely admitting it to myself, that I wouldn't mind dancing to it one day. When they finished their act, I tossed a hundred pesetas in the Gypsy woman's hat and, as the people started leaving the terrace, I finished off my gin and tonic and left.

When I got home I had a message on my answering machine from Figueras. He apologized and said something unexpected had arisen at the last minute and kept him from turning up to meet me; he asked me to call him. I called him. He apologized again and suggested another meeting.

'I have something for you,' he added.

'What?'

'I'll give it to you when we see each other.'

I told him I was going on holiday the following day (I was embarrassed to tell him I was going to Cancún) and wouldn't be back for a fortnight. We arranged to meet in the Núria in two weeks' time and, after going through the idiotic exercise of superficially describing ourselves to each other, said goodbye.

The Cancún thing was unspeakable. Conchi, who'd organized the trip, had hidden the fact that, except for a couple of excursions into the Yucatan peninsula and many afternoon shopping trips to the city centre, the whole thing amounted to spending two weeks trapped in a hotel with a gang of Catalans, Andalusians and North Americans ruled by a whistle-wielding tour guide and two monitors who had no understanding of the concept of rest and spoke not a word of Spanish; I'd be lying if I denied it had been years since I'd been so happy. And strange as it may seem, I believe without the stay in Cancún (or in a hotel in Cancún) I'd never have decided to write a book about Sánchez Mazas, because over the course of those days I had time to put my ideas about him in order and came to realize that the character and his story had over time turned into one of those obsessions that constitute the indispensable fuel for writing. Sitting on the balcony of my room with a mojito in hand, while watching how Conchi and her gang of Catalans, Andalusians and North Americans were relentlessly pursued, the length and breadth of the hotel, by the fury of the sports monitors ('Now, swimming-pool!'), I couldn't stop thinking about Sánchez Mazas. I soon arrived at a conclusion: the more I knew about him, the less I understood him; the less I understood him, the more he intrigued me; the more he intrigued me, the more I wanted to know about him. I had known — but not understood and was intrigued — that cultured, refined, melancholic and conservative man, bereft of physical courage and allergic to violence, undoubtedly because he knew himself incapable of exercising it, had worked during the twenties and thirties harder than almost anyone so that his country would be submerged in a savage orgy of blood. I don't know who it was who said: no matter who wins a war, the poets always lose. I do know that, just before my vacation in Cancún, I'd read that, on 29 October 1933, in the first public act of the Spanish Falange in the Madrid Drama Theatre, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, who was always surrounded by poets, had said 'people have never been moved except by their poets'. The first statement is stupid, not the second: it's true that wars are made for money, which is power, but young men go off to the front and kill and get killed for words, which are poetry, and that's why poets are always the ones who win wars; and for this reason Sánchez Mazas — who from his position of privilege at José Antonio's side contrived a violent patriotic poetry of sacrifice and yokes and arrows and the usual cries that inflamed the imaginations of hundreds of youths and would eventually send them to slaughter — is more responsible for the victory of Francoist arms than all the inept military manoeuvres of that nineteenth-century general who was Francisco Franco. I'd known but not understood and was intrigued — that, at the end of the war he had contributed more than almost anyone to starting, Franco had named him to a ministerial post in the first government of the Victory, but after a very short time had dismissed him because, rumour has it, he didn't even show up to the cabinet meetings and that from then on Sánchez Mazas abandoned active politics almost entirely and, as if he felt satisfied with the regime of grief he'd helped install in Spain and considered his work to be done, devoting the last twenty years of his life to writing, squandering his inheritance and filling his extensive leisure hours with rather extravagant hobbies. I was intrigued by that final era of retirement and peevishness, but most of all by the three war years, with their inextricable peripeteia, astonishing execution, militiaman saviour and forest friends, so one evening in Cancún (or in a Cancún hotel), as I whiled away the time before supper in the bar, I decided that, after almost ten years without writing a book, the moment to try again had arrived, and I also decided that the book I'd write would not be a novel, but simply a true tale, a tale cut from the cloth of reality, concocted out of true events and characters, a tale centred on Sánchez Mazas and the firing squad and the circumstances leading up to and following it.

Back from Cancún, I went to the Núria on the agreed evening to meet Figueras and arrived early as usual but hadn't yet ordered my gin and tonic when I was approached by a solid, stoop-shouldered man in his early fifties, with curly hair, deep blue eyes, and a modest rural smile. It was Jaume Figueras. Doubtless because I'd expected a much older man (as with Aguirre), I thought: The telephone puts on years. He ordered a coffee; I ordered a gin and tonic. Figueras apologized for not having shown up last time and for not being able to stay long this time. He explained that work piled up at that time of year and since he'd also put Can Pigem, the family house in Cornellá de Terri, up for sale, he was very busy putting his father's papers in order; his father had died ten years ago. At this point Figueras' voice broke: with a moist glimmer sparkling in his eyes, he swallowed, then smiled as if apologizing again. The waiter relieved the awkward silence by bringing the coffee and gin and tonic. Figueras took a sip of coffee.

'Is it true you're going to write about my father and Sánchez Mazas?' he sprung on me.

'Who told you that?'

'Miquel Aguirre.'

A true tale, I thought, but didn't say. That's what I'm going to write. It also occurred to me that Figueras was thinking if someone wrote about his father, his father wouldn't be entirely dead. Figueras insisted:

'I might,' I lied. 'I don't know yet. Did your father often tell you about how he met Sánchez Mazas?'

Figueras said yes. He admitted though that he had no more than a vague knowledge of the facts.

'You have to understand,' he apologized again. 'It was just one of those family stories. I heard my father tell it so many times. . At home, in the bar, on his own with us or surrounded by people from the village, because we had a bar in Can Pigem for years. Anyway. I don't think I ever paid much attention. And now I regret it.'

What Figueras knew was that his father had fought the whole war for the Republic, and that when he came home, towards the end, he'd met up with his younger brother, Joaquim, and a friend of his, called Daniel Angelats, who had just deserted from the Republican ranks. He also knew that, since none of the three soldiers wanted to go into exile with the defeated army, they decided to await the imminent arrival of Franco's troops hidden in a nearby forest, and one day they saw a half-blind man groping his way towards them through the undergrowth. They stopped him at gunpoint; they demanded he identify himself: the man said his name was Rafael Sánchez Mazas and that he was the most senior Falangist in Spain.

'My father knew who he was straightaway,' said Jaume Figueras. 'He was very well-read, he'd seen photos of Sánchez Mazas in the newspaper and had read his articles. Or at least that's what he always said. I don't know if it was true.'

'It could be,' I conceded. 'And then what happened?'

'They spent a few days hiding in the woods,' Figueras went on, after drinking the rest of his coffee. 'The four of them. Until the Nationalists arrived.'

'Didn't your father tell you what he talked about with Sánchez Mazas during the days they spent in the forest?'

'I suppose he must have,' Figueras answered. 'But I don't remember. Like I told you, I didn't pay much attention to those things. The only thing I remember is that Sánchez Mazas told them about the firing squad at Collell. You know the story, right?'

I nodded.

'He told them lots of other things too, that's for sure,'

Figueras continued. 'My father always said that over the course of those days he and Sánchez Mazas became good friends.' Figueras knew that, after the war, his father had been in prison, and that his family had begged him many times in vain to write to Sánchez Mazas, who was then a Minister, to ask him to intercede on his behalf. He also knew that once his father had got out of jail, he heard that someone from his village or from a village nearby, aware of the bonds of friendship between them, had written a letter to Sánchez Mazas in which he'd claimed to be one of the forest friends, and requested a gift of money as payment for the war debt, and that his father had written to Sánchez Mazas denouncing the impostor.

'Did Sánchez Mazas reply?'

'I think so, but I'm not sure. I haven't found any letters from him among my father's papers so far, and I shouldn't think he'd have thrown them away, he was a very careful man, he kept everything. I don't know, maybe they got misplaced, or maybe they'll turn up one of these days.' Figueras put his hand in his shirt pocket: slowly and deliberately. 'What I did find was this.'

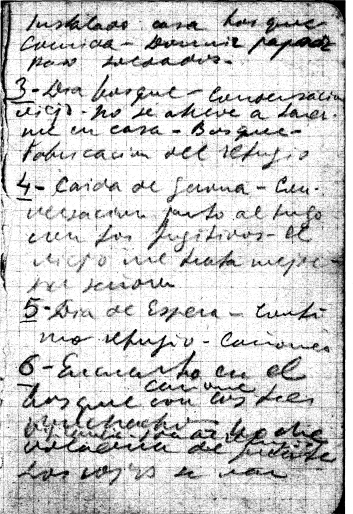

He handed me a small, old notebook, with blackened oilcloth covers which had once been green. I leafed through it. Most of it was blank, but several of the first and last pages were scribbled on in pencil, with hurried but not entirely illegible handwriting that barely stood out against the dirty cream-coloured, squared paper; my first glance through it also revealed that several pages had been torn out.

'What's this?' I asked.

'The diary Sánchez Mazas had with him when he was in hiding in the forest,' Figueras replied. 'Or that's what it looks like. Keep it; but don't lose it, it's like a family heirloom, my father was very attached to it.' He looked at his wristwatch, tutted to himself and said: 'Well, I have to be off now. But call me another day.'

As he stood up, leaning his thick callused fingers on the table, he added:

'If you want I can show you the place in the woods where they hid, the Mas de la Casa Nova; it's just a half-ruined farm nowadays, but if you're going to tell the story you'll want to see it. Of course if you're not thinking of telling it. .'

'I still don't know what I'll do,' I lied again, caressing the oilcloth covers of the notebook, which burned in my hands like a treasure. With the aim of spurring Figueras' memory, I added quite honestly: 'But, the truth is, I thought you'd have more to tell me.'

'I've told you all I know,' he apologized for the umpteenth time — but now I seemed to glimpse a touch of guile or distrust on the watery surface of his blue eyes. 'Anyway, if you do plan to write about Sánchez Mazas and my father, you should really talk to my uncle. He definitely knows all the details.'

'What uncle?'

'My uncle Joaquim.' He explained: 'My father's brother. Another one of the forest friends.'

Incredulous, as if he'd just announced the resurrection of one of the soldiers of Salamis, I asked:

'He's alive?'

'I should think so!' Figueras laughed uneasily, and an artificial hand gesture made me think he was only pretending to be surprised at my surprise. 'Didn't I tell you? He lives in Medinya but he spends a lot of time at the seaside in Montgo, and in Oslo too, because his son works there, for the WHO. I don't think you'll find him now, but in September I'm sure he'll be delighted to talk to you. Do you want me to suggest it to him?'

Slightly stunned by the news, I said of course I would.

'While I'm at it I'll see if I can find out Angelats' whereabouts,' said Figueras not hiding his satisfaction. 'He used to live in Banyoles, and he's probably still alive. Someone who definitely is, is Maria Ferré.'

'Who's Maria Ferré?'

Figueras visibly suppressed the urge to dig out an explanation.

'I'll tell you another time,' he said after looking at his watch again; then he held out his hand. 'I have to go now. I'll call you when I've arranged something with my uncle. He'll tell you everything, chapter and verse. He's got a very good memory; you'll see. Meanwhile, have a look at the notebook, I think it'll be of interest.'

I watched him pay, leave the Núria, get into a dusty jeep, carelessly parked at the entrance to the bar, and drive away. I stroked the notebook, but didn't open it. I finished drinking my gin and tonic and as I was getting up to go, saw an intercity train cross the viaduct behind the terrace full of people, and I thought of the Gypsies playing paso dobles two weeks ago in the tired light of an evening like this one and, when I got home and started to examine the notebook Figueras had entrusted to me, I'd still not disentangled the hauntingly sad melody of 'Sighing for Spain' from my memory.

I spent the night mulling over the notebook. In the first part it contained, after a few torn-out pages, a short diary written in pencil. Making an effort to decipher the handwriting, I read:

. . settled by forest house — Food — Slept hayloft — Soldiers passed.

3-Day in Forest — Conversation old man — Doesn't dare have me in house — Forest — Build shelter.

4-Fall of Gerona — Conversation by fireside with fugitives — Old man treats me better than his wife does.

5-Waiting all day — stay hidden — Cannon fire.

6-Meet three lads in forest Night Vigilance [illegible word] shelter — Bridges blown up — The reds are leaving.

7-Meet the three lads in the morning — Modest lunch from what friends had.

The diary stops there. At the end of the notebook, after more torn out pages, written in different handwriting, but also in pencil, are the names of the three lads, the forest friends:

Pedro Figueras Bahí

Joaqufn Figueras Bahí

Daniel Angelats Dilmé

And further down:

Casa Pigem de Cornelià

(across from the station)

Further down are the signatures, in ink — not pencil, like the rest of the writing in the book — of the two Figueras brothers, and on the following page is written:

Palol de Rebardit

Casa Borrell

Ferré Family

On another page, also in pencil and in the same handwriting as the diary, except much clearer, is the longest text in the notebook. It says:

1, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, founding member of the Spanish Falange, national adviser, ex-president of the Leadership Council and at present the senior Falangist in Spain and highest ranking in red territory, hereby declare:

1. that on the 30th of January 1939 I faced a firing squad at the Collell prison camp with 48 other unhappy prisoners and escaped miraculously after the first two rounds, breaking away into the forest —

2. that after three days' march through the forest, walking at night and asking for charity at the farms, I arrived in the area of Palol de Rebardit, where I fell into an irrigation ditch and lost my spectacles, leaving me half blind. .

There's a page missing here, which has been torn out. But the text goes on:

. . proximity of front line kept me hidden in their house until the Nationalist troops arrived.

4. that despite the generous objection of the inhabitants of the Borrell farm I wish by means of this document to confirm my promise to repay them with a substantial monetary reward, proposing the proprietor [here there is a blank space] for an honorary distinction if the military command is in agreement and to swear my immense and eternal gratitude to him and his family, all of which will be very little in comparison to what he has done for me.

Signed in the Casanova de un Pla farm near Cornellá de Terriat 1. .

That was the contents of the notebook. I reread it several times, trying to give those dispersed notes a coherent meaning, and link them to the facts I knew. To begin with, I discarded the suspicion, which insidiously crossed my mind as I read, that the notebook was a fraud, a falsification contrived by the Figueras family to deceive me, or to deceive someone: at the time I thought it didn't make much sense that a modest rural family would concoct so sophisticated a scheme. So sophisticated and, most of all, so absurd. Because, when Sánchez Mazas was alive, when it could have been a shield for defeated people against the reprisals of the victors, the document could easily have been authenticated and, once he was dead, it lost its value. Nevertheless, I thought that it would be a good idea to make sure the handwriting in the notebook (or one of the handwritings in the notebook, because there were several) and that of Sánchez Mazas were the same. If that were the case (and nothing led me to believe it wasn't), Sánchez Mazas was the author of the little diary, which had undoubtedly been written during the days he spent wandering in the forest, or at most very shortly afterwards. To judge by the last text in the notebook, Sánchez Mazas knew the date of the execution had been 30 January 1939; in any case the numeration preceding each entry of the diary corresponded to the days of the month of February of the same year (the Nationalists had indeed taken Gerona on 4 February). From the text of the diary I deduced that, before availing himself of the protection of the Figueras brothers and Angelats, Sánchez Mazas had found a more or less secure refuge in a house in the area, and this house could be none other than the Borrell house or farm, whose inhabitants he thanked and promised a 'substantial monetary reward' and 'an honorary distinction' in the long final declaration, and I also deduced that this house or farm must be in Palol de Rebardit — a municipality bordering on Cornellá de Terri — and that its inhabitants could only be the Ferré family, one of whom was sure to be Maria Ferré, who, as Jaume Figueras had told me at the sudden end of our interview in the Núria, was still alive. All of the above seemed obvious, just as, once fitted together, the place for each piece of a jigsaw puzzle seems obvious. As far as the final declaration went, drawn up in the Mas de la Casa Nova, the place in the forest where the four fugitives had stayed hidden — and undoubtedly when they knew themselves to be safe — it also seemed obvious that it was a way of formalizing Sánchez Mazas' debt to those who'd saved his life, like a safe-conduct enabling them to cross the uncertainties of the immediate post-war period, without having to undergo each and every one of the outrages reserved for the majority of those who, like the Figueras brothers and Angelats, had swelled the ranks of the Republican army. I found it strange, however, that one of the pages torn out of the notebook should be precisely the one containing the declaration in which, it could be inferred, Sánchez Mazas expressed his gratitude to the Figueras brothers and Angelats. I wondered who had torn out that page. And why. I wondered who had torn out the first pages of the notebook, and why. Since every question leads to another, I also wondered — in fact I'd already been wondering this for quite a while — what really happened during those days that Sánchez Mazas wandered aimlessly through the forest in no man's land. What did he think about, what did he feel, what did he tell the Ferrés, the Figueras brothers, Angelats? What did they remember him having told them? And what had they thought and felt? I was yearning to talk to Jaume Figueras' uncle, to Maria Ferré and Angelats, if he were still alive. I told myself, even if Jaume Figueras' tale couldn't be considered trustworthy (or couldn't be considered any more trustworthy than Ferlosio's), for its veracity didn't depend on a memory (his), but on the memory of a memory (his father's) — the accounts of his uncle, Maria Ferré and Angelats (if he was still alive) were on the other hand firsthand reports and therefore, at least at first, much less random than his. I wondered if those tales would fit the reality of events or whether, perhaps inevitably, they'd be varnished with that gloss of half-truth and fibs that always augment an episode now distant and perhaps legendary to its protagonists, so that what they might tell me had happened wouldn't be what really happened or even what they remembered happening, but what they remembered telling before.