Примечания

1. Genesis 3: 7, 21.

2. Ralf Kitiler, Manfred Kayser, and Mark Stoneking, "Molecular Evolution of Pediculus Humanus and the Origin of Clothing," Current Biology 13:1414–1417 (2003). Ряд специалистов оспаривает точность описанного исследования. Если их возражения обоснованы, дата изобретения одежды и появления платяной вши должна значительно отодвинуться вглубь времен, вплоть до 500 000 лет назад.

David L. Reed et al., "Genetic Analysis of Lice Supports Direct Contact between Modern and Archaic Hu mans," Public Library of Science Biology 2:1972–1983 (2004); Nicholas Wade, "What a Story Lice Can Tell," New York Times, October 5, 2004, p. F1.

3. Feng-Chi Chen and Wen-Hsiung Li, "Genomic Divergences between Humans and Other Hominoids and the Effective Population Size of the Common Ancestor of Hu mans and Chimpanzees," American Journal of Human Genetics 68:444–456 (2001).

4. Pascal Gagneux et al., "Mitochondrial Sequences Show Diverse Evolutionary Histories of African Hominoids," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96:5077–5082 (1999).

5. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 251. Если не указано иначе, палеоантропологические и археологические факты почерпнуты в основном из этой всеобъемлющей и ясной книги или из основанного на ней более популярного сочинения, The Dawn of Human Culture by Richard G. Klein and Blake Edgar, John Wiley & Sons, 2002.

6. Chen and Li, "Genomic Divergences." Число различий в ДНК между двумя видами зависит от размера предковой популяции и от срока (в поколениях), в течение которого виды расходятся. Если продолжительность поколения и период в годах, истекший после разветвления, известны, генетики могут оценить так называемый эффективный размер популяции. Это теоретическая величина, которую нужно умножать на коэффициент от двух до пяти, чтобы получить реальную численность.

7. P S. Rodman, in Adaptations for Foraging in Non-human Primates, Columbia University Press 1984, pp. 134–160, cited in Robert Foley, Humans before Humanity, Black-well, 1995, p. 140.

8. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1999, figure 8.3, p. 580.

9. Roger Lewin and Robert A. Foley, Principles of Human Evolution, 2 nd ed., Blackwell 2004, p. 450.

10. Robert Foley, Humans before Humanity, Blackwell, 1995, p. 170.

11. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, p. 292.

12. Richard Wrangham, "Out of the Pan, Into the Fire," in Frans В. M. De-Waal, ed., Tree of Origin, Harvard University Press, 2001, p. 137.

13. Richard G. Klein and Blake Edgar, The Dawn of Human Culture, Wiley, 2002, p. 100; Robert A. Foley, "Evolutionary Perspectives," in W. G. Runciman, ed., The Origin of Human Social Institutions, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 171–196.

14. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, p. 292.

15. Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, 2nd edition 1874, p. 58.

16. Mark Pagel and Walter Bodmer, "A Naked Ape Would Have Fewer Parasites," Proceedings of the Royal Society В (Suppl.) 270: S117-S119 (2003).

17. Rosalind M. Harding et al., "Evidence for Variable Selective Pressures at MC1R," American Journal of Human Genetics 66:1351–1361 (2000).

18. Nina G. Jablonski and George Chaplin, "The Evolution of Human Skin Coloration," Journal of Human Evolution 39:57–106 (2000).

19. Alan R. Rogers, David Litis, and Stephen Wooding, "Genetic Variation at the MC1R Locus and the Time Since Loss of Human Body Hair," Current Anthropology 45:105–108 (2004).

20. Nina G. Jablonski and George Chaplin, "Skin," Scientific American 74:72–79 (2002).

21. Arthur H. Neufeld and Glenn C. Conroy, "Human Head Hair Is Not Fur," Evolutionary Anthropology 13:89 (2004); B. Thierry, "Hair Grows to Be Cut," Evolutionary Anthropology 14:5 (2005); Alison Jolly, "Hair Signals,"Evolutionary Anthropology 14:5 (2005).

22. Hermelita Winter et al., "Human Type I Hair Keratin Pseudogene phihHaA. Has Functional Orthologs in the Chimpanzee and Gorilla: Evidence for Recent Inactivation of the Human Gene After the Pan-Homo Divergence." Human Genetics 108:37–42 (2001).

23. R. X. Zhu et al., "New Evidence on the Earliest Human Presence at High Northern Latitudes in Northeast Asia," Nature 431:559–562 (2004).

24. Robert Foley, Humans before Humanity, Blackwell, 1995, p. 75.

25. Richard G. Klein, "Archeology and the Evolution of Human Behavior," Evolutionary Anthropology 9 (1): 17–36 (2000).

26. Richard Klein and Blake Edgar, The Dawn of Human Culture, p. 192.

27. Richard Klein, The Human Career, p. 512.

28. Ian McDougall et al., "Stratigraphic Placement and Age of Modern Humans from Kibish, Ethiopia," Nature 433:733–736 (2005).

29. Из списка 15 поведенческих моделей, составленного Полом Мелларсом в "The Impossible Coincidence — A Single-Species Model for the Origins of Modern Human Behavior in Europe," Evolutionary Anthropology 14:12–27 (2005).

30. Richard Klein, The Human Career, p. 492.

31. Sally McBrearty and Alison S. Brooks, "The Revolution That Wasn't: A New Interpretation of the Origin of Modern Human Behavior," Journal of Human Evolution 39:453–563 (2000).

32. Christopher Henshilwood et al., "Middle Stone Age Shell Beads from South Africa," Science 304:404 (2004).

33. James M. Bowler et al., "New Ages for Human Occupation and Climatic Change at Lake Mungo, Australia," Nature 421:837–840 (2003).

34. Michael C. Corballis, "From Hand to Mouth: The Gestural Origins of Language," in Morten H. Christiansen and Simon Kirby, Language Evolution, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 201–219.

35. Marc D Hauser, The Evolution of Communication, MIT Press, 1996, p. 309.

36. Там же, с. 38.

37. Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct, William Morrow, 1994, p. 339.

38. Marc D Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and W. Tecumseh Fitch, "The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve?" Science 298:1569–1579 (2002).

39. Derek Bickerton, Language and Species, University of Chicago Press, 1990, p. 105.

40. Ray Jackendoff, Foundations of Language, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 233.

41. Frederick J. Newmeyer, "What Can the Field of Linguistics Tell Us about the Origins of Language?" in Language Evolution, by Morten H. Christiansen and Simon Kirby, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 60.

42. Nicholas Wade, "Early Voices: The Leap of Language," New York Times, July 15, 2003, p. F1.

43. Steven Pinker, e-mail, June 16, 2003, quoted in part in Wade, "Early Voices."

44. Steven Pinker and Paul Bloom, "Natural Language and Natural Selection,"Behavioral and Brain Sciences 13 (4):707–784 (1990).

45. Derek Bickerton, Language and Species, p. 116.

46. Ray Jackendoff, Foundations of Language, p. 240.

47. Ann Senghas, Sogaro Kita, and Asli Ozyurek, "Children Creating Core Properties of Language: Evidence from an Emerging Sign Language in Nicaragua," Science 305:1779–1782 (2004).

48. Wendy Sandler et al., "The Emergence of Grammar: Systematic Structure in a New Language," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102:2661–2665 (2005).

49. Nicholas Wade, "Deaf Children's Ad Hoc Language Evolves and Instructs,"New York Times, September 21, 2004, p. F4.

50. Michael C. Corballis, "From Hand to Mouth," p. 205.

51. Louise Barrett, Robin Dunbar, and John Lycett, Human Evolutionary Psychology, Princeton University Press, 2002.

52. Geoffrey Miller, The Mating Mind, Random House, 2000.

53. Steven Pinker, "Language as an Adaptation to the Cognitive Niche," in Morten H. Christiansen and Simon Kirby, Language Evolution, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 29.

54. Paul Mellars, "Neanderthals, Modern Humans and the Archaeological Evidence for Language," in Nina G. Jablonski and Leslie C. Aiello, eds., The Origin and Diversification of Language, California Academy of Sciences, 1988, p. 99.

55. Faraneh Vargha-Khadem, interview, October 1, 2001.

56. Faraneh Vargha-Khadem, Kate Watkins, Katie Alcock, Paul Fletcher, arid Richard Passingham, "Praxic and Nonverbal Cognitive Deficits in a Large Family with a Genetically Transmitted Speech and Language Disorder," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 92:930–933 (1995).

57. Faveneh Vargha-Khadem et al., "Neural Basis of an Inherited Speech and Language Disorder," Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 95:12659–12700 (1998).

58. Многие гены открыли биологи, ставящие опыты на плодовых мушках, а у этих ученых принято давать генам яркие названия. Такие странные названия нередко присваивают открытым позже эквивалентным человеческим генам; отсеиваются лишь слишком яркие типа «олуха» или «страхолюдины». Вилоголовый (forkhead) ген получил такое прозвание потому, что, когда он мутирует, у личинки плодовой мушки на голове образуются своего рода шипы. Обнаружены и другие гены подобной структуры, у них в ДНК есть сигнатурный бокс, названный вилоголовым (forkhead box), он помечает участок в forkhead-белке, который привязывается к той или иной последовательности ДНК. Дело в том, что этот белок контролирует работу других генов, присоединяясь к участкам ДНК, следующим сразу за этими генами. У человека оказалось целое семейство генов с боксом вилоголовости, его подгруппы обозначаются буквами латинского алфавита. Ген FOХP2 — второй в подгруппе. P. Gary F Marcus and Simon К Fisher, "FOXP2 in locus: What Can Genes Tell Us About Speech and Language?" Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7:257–262 (2003).

59. Cecilia S. L. Lai, Simon E. Fisher, Jane A. Hurst, Faraneh Vargha-Khadem, and An thony P Monaco, "A Forkhead-Domain Gene Is Mutated in a Severe Speech and Language Disorder," Nature 413:519–523 (2001).

60. Faraneh Vargha-Khadem et al., "FOXP2 and the Neuroanatomy of Speech and Language," Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6:131–138 (2005).

61. Wolfgang Enard et al., "Molecular Evolution of FOXP2, a Gene Involved in Speech and Language," Nature 418:869–872 (2002).

62. Svante Paabo, interview, August 10, 2002.

63. Richard Klein, The Human Career, University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 492.

64. Причина, вероятно, в том, что соперничество между митохондриями внутри клетки было бы слишком разрушительным. Митохондрии сперматозоида как бы несут на себе химический ярлык «Убей меня». Лишь только сперматозоид проникнет в яйцеклетку, его митохондрии разрушаются. В яйцеклетке имеется около 100 000 своих митохондрий, и она не нуждается в сотне, предлагаемых сперматозоидом. Douglas C. Wallace, Michael D. Brown, and Marie T Lott, "Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Human Evolution and Disease," Gene, 238:211–230 (1999).

65. Peter A. Underhill et al., "Y Chromosome Sequence Variation and the History of Hu man Populations," Nature Genetics, 26:358–361 (2000).

66. S. T. Sherry, M. A. Batzer, and H. C. Harpending, "Modeling the Genetic Architecture of Modern Populations," Annual Review of Anthropology 27:153–169 (1968).

67. Jonathan K. Pritchard, Mark T. Seielstad, Anna Perez-Lezaun, and Marcus W. Feldman, "Population Growth of Human Y Chromosomes: A Study of Y Chromosome Micro-satellites," Molecular Biology and Evolution 16:1791–1798 (1999).

68. P A. Underhill, G. Passarino, A. A. Lin, P Shen, M. Mirazon-Lahr, R. A. Foley, P J. Oefner, and L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, "The Phylogeography of Y Chromosome Binary Haplotypes and the Origins of Modern Human Populations," Annals of Human Genetics 65:43–62 (2001).

69. S. T. Sherry et al., "Modeling the Genetic Architecture of Modern Populations," p. 166.

70. Richard Borshay Lee, The iKung San, Cambridge University Press, 1979, p. 31.

71. Tom Giildemann and Rainer Vossen, "Khoisan," in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

72. Yu-Sheng Chen et al., "mtDNA Variation in the South African Kung and Khwe — and Their Genetic Relationships to Other African Populations, "American Journal of Human Genetics 66:1362–1383 (2000). The team sampled a group of IKung from the northwestern Kalahari Desert known as the Vasikela IKung.

73. Alec Knight et al., "African Y Chromosome and mtDNA Divergence Provides Insight into the History of Click Languages," Current Biology 13:464–473 (2003).

74. Nicholas Wade, "In Click Languages, an Echo of the Tongues of the Ancients, "New York Times, March 18, 2003, p. F2.

75. Ornella Semino et al., "Ethiopians and Khoisan Share the Deepest Clades of the Human Y-Chromosome Phylogeny," American Journal of Human Genetics 70:265–268 (2002).

76. Donald E. Brown, Human Universals, McGraw-Hill, 1991, p. 139.

77. Henry Harpending and Alan R. Rogers, "Genetic Perspectives on Human Origins and Differentiation," Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 1:361–385 (2000).

78. Richard Borshay Lee, The IKung San, Cambridge University Press, 1979, p. 135.

79. Jon de la Harpe et al., "Diamphotoxin, the Arrow Poison of the IKung Bushmen," Journal of Biological Chemistry 258:11924–11931 (1983).

80. Richard Borshay Lee, The IKung San, p. 440.

81. Nancy 1 lowell, Demography of the Dohe IKung, Academic Press, 1979, p. 119.

82. «Безобидные», как отмечает Элизбет Маршалл Томас в своей новой книге The Old Way, — один из возможных переводов самоназвания бушменского племени жуцъоан. Томас пишет, что в свете его экологической устойчивости и продолжительности существования минимум в 35 000 лет образ жизни бушменов был «самой успешной культурой, которую только знало человечество». Яркий рассказ от первого лица о жизни охотников и собирателей, содержащийся в книге Томас, дополняет антропологическое исследование Ричарда Борсей Ли. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, The Old Way — A Story of the First People, Farrar Strauss Giroux," 2006.

83. Steven A. LeBlanc, Constant Battles, St. Martin's Press, 2003, p. 116.

84. Lawrence H. Keeley, "War before Civilization," Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 134.

85. Richard Borshay Lee, The IKung San, p. 399. The odd symbols represent different kinds of click.

86. Frank W. Marlowe, "Hunter-Gatherers and Human Evolution," Evolutionary Anthropology 14:54–67 (2005).

87. M. Siddall et al., "Sea-Level Fluctuations during the Last Glacial Cycle," Nature 423:853–858.

88. Exodus 15:8.

89. Sarah A. Tishkoff and Brian C. Verrelli, "Patterns of Human Genetic Diversity: Implications for Human Evolutionary History and Disease," Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 4:293–340 (2003).

90. Jeffrey I. Rose, "The Question of Upper Pleistocene Connections between East Africa and South Arabia," Current Anthropology 45:551–555 (2004).

91. Luis Quintana-Murci et al., "Genetic Evidence of an Early Exit of Homo sapiens from Africa through Eastern Africa," Nature Genetics 23:437–441 (1999).

92. Martin Richards et al., "Extensive Female-Mediated Gene Flow from Sub-Saharan Africa into Near Eastern Arab Populations," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:1058–1064 (2003).

93. John D. H. Stead and Alec J. Jeffreys, "Structural Analysis of Insulin Minisatellite Alle les Reveals Unusually Large Differences in Diversity between Africans and Non-Africans," American Journal of Human Genetics 71:1273–1284 (2002).

94. Nicholas Wade, "To People the World, Start with 500," New York Times, November 11, 1997, p. F1.

95. Vincent Macaulay et al., "Single, Rapid Coastal Settlement of Asia Revealed by Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genomes," Science 308:1034–1036 (2005). Генетики полностью расшифровали митохондриальные ДНК людей, принадлежащих к ветвям M и N, которые первыми вышли за пределы Африки, и сравнили их с L3, внутриафриканской линией, от которой те две ответвились. Зная темп, в котором митохондриальная ДНК накапливает мутации, ученые подсчитали, что линии M и N отделились от L3 826 поколений или 20 650 лет назад. Время, необходимое для такого рода трансформаций, зависит от численности популяции, и если оно известно, размер исходной популяции можно установить. Получается, что это были 550 женщин репродуктивного возраста, если популяция не менялась в размере в течение 20 000 лет, а если росла, как оно, несомненно, было, то и того меньше.

96. T. Kivisild et al., "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:313–332 (2003).

97. Richard G. Roberts et al., "New Ages for the Last Australian Megafauna: Continent-Wide Extinction About 46,000 Years Ago," Science 292:1888–1892 (2001).

98. Vincent Macaulay et al., "Single, Rapid Coastal Settlement of Asia."

99. Kirsi Huoponen, Theodore G. Schurr, Yu-Sheng Chen, and Douglas C. Wallace, "Mitochondrial DNA Variation in an Aboriginal Australian Population: Evidence for Genetic Isolation and Regional Differentiation, "Human Immunology 62:954–969 (2001).

100. Max Ingman and Ulf Gyllensten, "Mitochondrial Genome Variation and Evolutionary History of Australian and New Guinean Aborigines," Genome Research 13:1600–1606 (2003).

101. Steven A. LeBlanc, Constant Battles, St. Martin's Press, 2003, p. 121.

102. Manfred Kayser et al., "Reduced Y-Chromosome, but Not Mitochondrial DNA, Diversity in Human Populations from West New Guinea," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:281–302 (2003).

103. Steven A. LeBlanc, Constant Battles, p. 151.

104. Nicholas Wade, "An Ancient Link to Africa Lives On in the Bay of Bengal," New York Times, December 10, 2002, p. A14.

105. Kumarasamy Thangaraj et al., "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population," Current Biology 13:86–93 (2003).

106. Philip Endicott et al., "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:1590–1593 (2003).

107. Madhusree Mukerjee, The Land of Naked People, Houghton Mifflin, 2003, p. 240.

108. Stephen Oppenheimer, The Real Eve, Carroll & Graf, 2003, p. 218.

109. David L. Reed et al., "Genetic Analysis of Lice Supports Direct Contact Between Mod ern and Archaic Humans," Public Library of Science Biology 2. 1972–1983 (2004); Nicholas Wade, "What a Story Lice Can Tell," New York Times, October 5, 2004, p. F1. Второй подвид вшей обнаруживается только в Америке, как если бы современные люди заразились им от Homo erectus на Дальнем Востоке или в Сибири перед миграцией через плейстоценовый перешеек, соединявший Сибирь и Северную Америку. Вероятно, этот подвид вши доминировал в Америке, пока европейские колонисты не завезли туда другой, «стандартный» для остального мира.

110. P. Brown et al., "A New Small-Bodied Hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia," Nature 431:1055–1091 (2004); Nicholas Wade, "New Species Revealed: Tiny Cousins of Humans," New York Times, October 28, 2004, p. A1; Nicholas Wade, "Miniature People Add Extra Pieces to Evolutionary Puzzle," New York Times, November 9, 2004, p. F2. M. J. Morwood et al., "Further evidence for small-bodied hominims from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia," Nature 437, 1012–1017, 2005.

111. Спор о том, к какому виду нужно отнести малюток-флоресийцев, достиг пика, когда несколько ученых предположили, что череп принадлежал патологически мелкогабаритному современному человеку. Новый взгляд, предложенный учеными из Австралийского национального университета и Сиднейского университета, предполагает, что флоресийцы не были ни патологической формой Homo sapiens, ни уменьшенной разновидностью Homo erectus, а произошли от другой, много более ранней трансафриканской миграции, возможно, еще в то время, когда остров Флорес был частью материка. Эта позиция основана на сходстве черепа по объему мозга и другим чертам с предшественником Homo erectus, Homo ergaster. Debbie Argue, Denise Don-Ion, Colin Groves, and Richard Wright, Homo floresiensis: Microcephalic, pygmoid, Australopithecus, or Homo?" Journal of Human Evolution 51, 360–374 (2006).

112. Roger Lewin and Robert A. Foley, Principles of Human Evolution, Blackwell Science, 2004, p. 387.

113. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 470.

114. Christopher Stringer and Robin McKie, African Exodus, Henry Holt, 1996, 1999, p. 106.

115. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, p. 477.

116. Matthias Krings et al., "Neanderthal DNA Sequences and the Origin of Modern Hu mans," Cell 90:19–30, 1997.

117. David Serre et al., "No Evidence of Neanderthal mtDNA Contribution to Early Mod ern Humans," Public Library of Science Biology 2:1–5 (2004).

118. Новая теория происхождения человека предполагает, что современные люди, покинув Африку, поначалу скрещивались с архантропами, когда волна миграции встречала на пути их племена. Теория прогнозирует, что на большинстве участков нуклеарного генома обнаружатся какие-нибудь архаические аллели. Vinyarak Eswaran, Henry Harpending, and Alan R. Rogers, "Genomics Refutes an Exclusively African Origin of Humans," Journal of Human Evolution 49:1–18 (2005).

119. Происхождение ориньякской культуры до сих пор темно. Если современные люди, как подсказывают данные генетики, пришли в Европу из Индии, то на Индийском субконтиненте должны сохраниться следы предшествующих культур. Однако пока археологические памятники Индии не особенно богаты свидетельствами сложного поведения, свойственного ориньякцам. (Hannah V A. James and Michael D. Petraglia, "Modern Human Origins and the Evolution of Behavior in the Later Pleistocene Record of South Asia," Current Anthropology, 46 [Supplement]: 3–27 [2005]). Возможно, элементы ориньякской культуры сформировались в какой-то момент миграции из Индии в Европу, когда первые современные люди, жившие до того в субтропиках, адаптировались к климату европейского ледникового периода.

120. Сегодня предполагается, что ориньякские орудия из этого памятника изготовлены современным человеком, жившим здесь в промежутках между периодами неандертальского владычества. Brad Gravina, Paul Mellars and Christopher Bronk Ramsey, "Radiocarbon Dating of Interstratifi ed Neanderthal and Early Modern Human Occupations at the Chatelperronian Type-Site," Nature 438:51–56 (2005).

121. Martin Richards, "The Neolithic Invasion of Europe," Annual Review of Anthropology 32:135–162 (2003).

122. Существенный пересмотр радиоуглеродной датировки показывает, что ориньякцы пришли в Европу раньше и распространились гораздо быстрее. Пересмотр был вызван: а) появлением новых методов отсева посторонних веществ, из-за которых древние источники углерода кажутся моложе, и б) новыми оценками количества атмосферного углерода-14 в далеком прошлом. С учетом этих двух поправок Пол Мелларс пересмотрел дату прибытия современных людей в Европу. По оценке Мелларса, они появились к западу от Черного моря уже 46 000 лет назад, а не 40 000–44 000 лет назад, как показано на рис. 5.2, и достигли северной Испании 41 000, а не 36 000 лет назад. Мелларс утверждает, что неандертальские останки из пещер Зафаррая в Испании и Виндия в Хорватии, возраст которых сегодня определен приблизительно в 30 000 лет, окажутся гораздо старше. Если так, то согласно новому расписанию неандертальцы исчезли много быстрее, чем считалось, — возможно, всего за 5000 лет. Быстрому продвижению современного человека могло поспособствовать улучшение климата, наблюдавшееся между 43 000 и 41 000 лет назад. Paul Mellars, "A New Radiocarbon Revolution and the Dispersal of Modern Humans in Eurasia," Nature 439:931–935 (2006).

123. Ofer Bar-Yosef, "The Upper Paleolithic Revolution," Annual Review of Anthropology 31:363–393 (2002).

124. Agnar Helgason et al., "An Icelandic Example of the Impact of Population Structure on Association Studies," Nature Genetics 37:90–95, 2005; Nicholas Wade, "Where Are You From? For Icelanders, the Answer Isin the Genes," New York Times, December 28, 2004, p. F3.

125. Patrick D. Evans et al., "Microcephalia a Gene Regulating Brain Size, Continues to Evolve Adaptively in Humans," Science 309:1717–1220 (2005); Nitzan Mekel-Bobrov, "Ongoing Adaptive Evolution of ASPM, a Brain Size Determinant in Homo sapiens," Science 309:1720–1722 (2005).

126. Nicholas Wade, "Brain May Still Be Evolving, Studies Hint," New York Times, September 9, 2005, p. A14.

127. Steve Dorus et al., "Accelerated Evolution of Nervous System Genes in the Origin of Homo sapiens," Cell 119:1027–1040 (2004).

128. Два Ланновых гена микроцефалина не проявились в пангеномном анализе, проведенном группой Джонатана Притчарда (см. прим. 256). Возможно, тест просто не сумел их выявить: нет идеальных методов анализа на отбор. Притчард обнаружил признаки отбора у двух других генов, частично виновных в микроцефалии, и в нескольких других группах мозговых генов. Какие-то из этих генов подвергались отбору у африканцев, другие у азиатов, свои — у европейцев, что и говорит в пользу теории Ланна о параллельной эволюции когнитивных способностей в этих трех популяциях. Многие генетические изменения, происходившие независимо в основных континентальных расах, вероятно, были конвергентными, то есть эволюция в разных популяциях прибегала к разным доступным ей мутациям, чтобы получить одни и те же механизмы приспособления.

129. Недавняя корректировка радиоуглеродного метода (см. прим. 122) показывает, что наскальные росписи в Шове значительно древнее, чем предполагалось. Сегодня можно сказать, что первые обитатели появились в пещере 36 000 лет назад.

130. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, 2nd edition, University of Chicago Press 1999, p. 540.

131. Martin Richards et al., "Tracing European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool," American Journal of Human Genetics 67:1251–1276 (2000); Martin Richards, "The Neolithic Invasion of Europe," Annual Review of Anthropology 32:135–162 (2003).

132. Antonio Torroni et al., "A Signal, from Human mtDNA, of Postglacial Recolonization in Europe," American Journal of Human Genetics 69:844–852 (2001).

133. Ornella Semino et al., "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective," Science 290:1155–1159, 2000.

134. Colin Renfrew, "Commodification and Institution in Group-Oriented and Individualizing Societies," in The Origin of Human Social Institutions, Oxford University Press 2001, p. 114.

135. Carles Vila et al., "Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog," Science 276:1687–1689 (1997).

136. Peter Savolainen et al., "Genetic Evidence for an East Asian Origin of Domestic Dogs," Science 298:1610–1616 (2002).

137. Lyudmila N. Trut, Early Canid Domestication: The Farm-Fox Experiment, "American Scientist 17:160–169 (1999).

138. Brian Hare, Michelle Brown, Christine Williamson, and Michael Tomasello, "The Domastication of Social Cognition in Dogs," Science 298:1634–1636 (2002).

139. Nicholas Wade, "From Wolf to Dog, Yes, but When?" New York Times, November 22, 2002, p. A20.

140. Jennifer A. Leonard et al., "Ancient DNA Evidence for Old World Origin of New World Dogs," Science 298:1613–1616 (2002).

141. Joseph H. Greenberg, Language in the Americas, Stanford University Press, 1987, p. 43.

142. Vivian Scheinsohn, "Hunter-Gatherer Archaeology in South America,"Annual Review of Anthropology 32:339–361 (2003).

143. Yelena B. Starikovskaya et al., "mtDNA Diversity in Chukchi and Siberian Eskimos: Implications for the Genetic History of Ancient Beringia and the Peopling of the New World," American Journal of Human Genetics 63:1473–1491 (1998).

144. Mark Seielstad et al., "A Novel Y-Chromosome Variant Puts an Upper Limit on the Timing of First Entry into the Americas," American Journal of Human Genetics 73:700–705 (2003).

145. Maria-Catira Bortolini et al., "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas," American Journal of Human Genetics 73:524–539 (2003).

146. Michael D. Brown et al., "mtDNA Haplogroup X: An Ancient Link between Europe/Western Asia and North America?" American Journal of Human Genetics 63:1852–1861 (1998).

147. Ripan S. Malhi and David Glenn Smith, "Haplogroup X Confirmed in Prehistoric North America," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 119:84–86 (2002).

148. Eduardo Ruiz-Pesini et al., "Effects of Purifying and Adaptive Selection on Regional Variation in Human mtDNA," Science 303:223–226; Dan Mishmar et al, "Natural Se lection Shaped Regional mtDNA Variation in Humans." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:171–176 (2003).

149. Mark T. Seielstad, Erich Minch, and L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza, "Genetic Evidence for a Higher Female Migration Rate in Humans," Nature Genetics 20:278–280 (1998).

150. Kennewick Man, the 9,000-year-old, non-Mongoloid-looking skeleton discovered in Washington state and claimed by sinodont American Indians as their intimate ances tor, is a sundadont.

151. Marta Mirazon Lahr, The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 318.

152. Ученые все больше убеждаются, что светлая кожа как модификация темной прародительской появилась в западной и восточной половине Евразии независимо, хотя причина в обоих случая была, очевидно, одна — ослабление солнечной радиации. Пять генов, влияющих на цвет кожи, несут на себе признаки недавнего отбора у европейцев, но не у азиатов (см. прим. 241 и 256). Это означает, что в азиатской популяции светлокожесть сформирована другим набором генов, либо азиаты приобрели ее намного раньше европейцев. При втором сценарии признаки селекции просто угасли, и потому тест Притчарда не подсвечивает эти гены.

153. В Африке и в Европе ушная сера у большинства людей влажная. Но в восточной Азии правилом будет сухая. Группа японских ученых установила, что разница объясняется мутацией в гене ABCC11. (Koh-ictum Yoshiura et al., "A SNP in the ABCC11 Gene Is the Determinant of Human Earwax Type," Nature Genetics 38:324–330 [2006].) Мутация, скорее всего, возникла в северной части восточной Азии и распространилась быстро — она практически универсальна у северных хань и у корейцев. Какой фактор отбора вызвал столь быстрое распространение новой версии гена? Ушная сера играет довольно скромную роль биологической мушиной липучки: она препятствует попаданию в ухо насекомых и грязи, и не похоже, чтобы изменение ее консистенции могло принести сколько-нибудь значимое преимущество. Похоже, что новая версия гена утвердилась потому что он, как предполагается, также уменьшает потоотделение, а следовательно, ослабляет запах тела. Видимо, какое-то из этих двух усовершенствований, если не оба, и обеспечили гену такое значительное преимущество.

154. Richard G. Klein, The Human Career, p. 502.

155. Ofer Bar-Yosef, "On the Nature of Transitions: The Middle to Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic Revolution," Cambridge Journal of Archaeology 8: (2): 141–163 (1998).

156. Ofer Bar-Yosef, "From Sedentary Foragers to Village Hierarchies," The Origin of Human Social Institutions, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 7.

157. Peter M. M. G. Akkermans and Glenn M. Schwartz, The Archaeology of Syria, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 45.

158. Brian M. Fagan, People of the Earth, 10th ed., Prentice Hall, 2001, p. 226.

159. The evidence included a Natufian skeleton with a Natufian type arrow point embedded in the thoracic vertebrae. Fanny Bocquentin and Ofer Bar-Yosef, "Early Natufian Remains: Evidence for Physical Conflict from Mt. Carmel, Israel," Journal of Human Evolution 47:19–23 (2004).

160. Akkermans and Schwartz, The Archaeology of Syria, p. 96.

161. Colin Renfrew, "Commodification and Institution in Group-Oriented and Individualizing Societies," in W. G. Runciman, ed., The Origin of Social Institutions, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 95.

162. Natalie D. Munro, "Zooarchaeological Measures of Hunting Pressure and Occupation Intensity in the Natufian," Current Anthropology 45: S5–33 (2004).

163. Akkermans and Schwartz, The Archaeology of Syria, p. 70.

164. Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, 3rd ed., Ox ford University Press, 2000, p. 18.

165. Robin Allaby, "Wheat Domestication," in Archaeogenetics: DNA and the Population Prehistory of Europe, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000, pp. 321–324.

166. Francesco Salamini et al., "Genetics and Geography of Wild Cereal Domestication in the Near East," Nature Reviews Genetics 3:429–441 (2002).

167. Manfred Heun et al., "Site of Einkorn Wheat Domestication Identified by DNA Fin gerprinting," Science 278:1312–1314 (1997); Daniel Zohary, and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, p. 36.

168. Francesco Salamini et al, "Genetics and Geography of Wild Cereal Domestication in the Near East."

169. Christopher S. Troy et al., "Genetic Evidence for Near-Eastern Origins of European Cattle," Nature 410:1088–1091 (2001).

170. Carlos Vila et al., "Widespread Origins of Domestic Horse Lineages," Science 291:474–477 (2001).

171. Вместе с тем Y-хромосома лошади повествует, похоже, о другом. Пробы из небольшого ее участка у 15 разных пород европейской и азиатской лошади оказались, не в пример митохондриальной ДНК, идентичными. Gabriella Litidgien et al., "Limited Number of Patrilines in Hotse Domestication," Nature Genetics 36:335–336 (2004). Отсюда следует, что древние коневоды, как и нынешние, часто давали одному жеребцу покрывать множество кобыл. А независимое одомашнивание лошадей, вероятно, не было таким уж распространенным явлением, как подсказывает анализ митохондриальной ДНК.

172. Такой вывод подтверждается непосредственным изучением первых неолитических аграриев, поселившихся в Европе. Ученые извлекли митохондриальную ДНК из костей, обнаруженных в археологических памятниках самых ранних (7500 лет назад) сельскохозяйственных сообществ из Германии, Австрии и Венгрии. Четверть всех образцов принадлежала подветви Nla на митохондриальном древе, а этот тип сегодня крайне редок среди европейцев. Следовательно, хотя неолитические сельскохозяйственные практики распространялись стремительно, сами аграрии не привнесли заметного генетического влияния. Авторы придерживаются мнения, что «сельское хозяйство в Европу принесли небольшие группы пионеров, и когда оно утвердилось, соседствующие собирательские сообщества переняли новую культуру и численно подавили исконных аграриев, размыв частотность Nla-ветви до современного низкого уровня». Wolfgang Haak et al., "Ancient DNA from the First European Farmers in 7500-Year-Old Neolithic Sites," Science 310:1016–1018 (2005).

173. Ornella Semino et al., "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: AY Chromosome Perspective," Science 290:1155–1159 (2000).

174. Roy King and Peter A. Underhill, "Congruent Distribution of Neolithic Painted Pottery and Ceramic Figurines with Y-Chromosome Lineages," Antiquity 76:707–714 (2002).

175. Благодарю свою читательницу, кулинарного обозревателя Энн Мендельсон, обратившую мое внимание на то, что во многих частях мира люди потребляют молоко только в сквашенном виде, в продуктах вроде йогурта, где лактоза уже трансформировалась благодаря работе бактерий в молочную кислоту. В таких условиях не возникает стимула для развития переносимости лактозы. Тем не менее она у человека возникла, так что люди культуры воронкообразных кубков, видимо, употребляли молоко парным, возможно, потому, что не умели сквашивать.

176. Albano Beja-Pereira et al., "Gene-Culture Coevolution between Cattle Milk Protein Genes and Human Lactase Genes," Nature Genetics 35:311–315 (2003).

177. Nabil Sabri Enattah et al., "Identification of a Variant Associated with Adult-type Hypolactasia," Nature Genetics 30:233–237 (2002).

178. Todd Bersaglieri et al., "Genetic Signatures of Strong Recent Positive Selection at the Lactase Gene," American Journal of Human Genetics 74:1111–1120 (2004).

179. Charlotte A. Mulcare et al., "The T Allele of a Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism 13.9 kb Upstream of the Lactase Gene (LCT) (C-13.9kbT) Does Not Predict or Cause the Lactase-Persistence Phenotype in Africans," American Journal of Human Genetics 74:1102–1110 (2004).

180. Napoleon Chagnon, "Life Histories, Blood Revenge, and Warfare in a Tribal Population," Science 239:985–992 (1988).

181. Anne E. Pusey, in Frans В. M. de Waal, ed., Tree of Origin, Harvard University Press 2001, p. 21.

182. John C. Mitani, David R Watts, and Martin N. Muller, "Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior," Evolutionary Anthropology 11:9–25 (2002).

183. Anne E. Pusey, Tree of Origin, p. 26.

184. Julie L. Constable, Mary V. Ashley, Jane Goodall, and Anne E. Pusey, "Noninvasive Paternity Assignment in Gombe Chimpanzees," Molecular Ecology 10:1279–1300 (2001).

185. Anne Pusey, Jennifer Williams, and Jane Goodall, "The Influence of Dominance Rank on the Reproductive Success of Female Chimpanzees," Science 277:828–831 (1997).

186. A. Whiten et al., "Cultures in Chimpanzees," Nature 399:682 (1999).

187. W. C. McGrew, "Tools Compared," in Richard W. Wrangham et al., eds.,Chimpanzee Cultures, Harvard University Press, 1994, p. 25.

188. Richard W. Wrangham et al., Demonic Males, Houghton Mifflin, 1996, p. 226.

189. Some experts argue that chimps are derived from bonobos, but the direction of change makes no difference here.

190. Frans de Waal, Our Inner Ape, Riverhead Books, 2005, p. 221.

191. John C. Mitani, David R Watts, and Martin N. Muller, "Recent Developments in the Study of Wild Chimpanzee Behavior," Evolutionary Anthropology 11:9–25 (2002).

192. Napoleon A. Chagnon, Yanomamo, 5th ed., Wadsworth, 1997, p. 189.

193. Там же, с. 97.

194. Lawrence H. Keeley, War before Civilization, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 174.

195. Там же, с. 33.

196. Steven A. LeBlanc, Constant Battles, St. Martin s Press, 2003, p. 8.

197. Simon Mead et al., "Balancing Selection at the Prion Protein Gene Consistent with Prehistoric Kurulike Epidemics," Science 300:640–643 (2003).

198. Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature, Harvard University Press, 1978, p. 114.

199. Louise Barrett, Robin Dunbar, and John Lycett, Human Evolutionary Psychology, Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 64.

200. Napoleon A. Chagnon, Yanomamo, 5th ed., Wadsworth, 1997, p. 76.

201. Napoleon Chagnon, "Life Histories, Blood Revenge, and Warfare in a Tribal Population," Science 239:985–992 (1988).

202. Napoleon A. Chagnon, Yanomamo, p. 77.

203. David M. Buss, Evolutionary Psychology, 2nd ed., Pearson Education, 2004, p. 257.

204. Robert L. Trivers, "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism," Quarterly Review of Biology 46:35–57, 1971.

205. Following Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works, W. W. Norton, 1997, pp. 404–405.

206. Matt Ridley, The Origins of Virtue, Viking, 1996, p. 197.

207. Paul Seabright, "The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life," Princeton University Press, 2004, p. 28.

208. Michael Kosfeld et al., "Oxytocin Increases Trust in Humans," Nature 435:673–676 (2005).

209. Roy A. Rappaport, "The Sacred in Human Evolution," Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 2:23–44 (1971).

210. Joyce Marcus and Kent V. Flannery, "The Coevolution of Ritual and Society: New HC Dates from Ancient Mexico," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 18252–18261 (2004).

211. Richard Sosis, "Why Aren't We all Hutterites?" Human Nature 14:91–127 (2003).

212. Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature, Harvard University Press, 1978, p. 175.

213. Frank W Marlowe, "A Critical Period for Provisioning by Hadza Men: Implications for Pair Bonding," Evolution and Human Behavior 24:217–229 (2003).

214. Tim Birkhead, Promiscuity, Harvard University Press, 2000, p. 41.

215. Nicholas Wade, "Battle of the Sexes is Discerned in Sperm," New York Times February 22, 2000, p. F1.

216. Alan F. Dixson, Primate Sexuality, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 218.

217. Gerald J. Wyckoff, Wen Wang, and Chung-I Wu, "Rapid Evolution of Male Reproductive Genes in the Descent of Man," Nature 403:304–309 (2000).

218. В репродуктивном тракте женщины сперматозоиды обычно живут не дольше 48 часов, хотя бывают случаи, когда они выживают и до пяти дней. Tim Birkhead, Promiscuity, p. 67. Tim Birkhead, Promiscuity, p. 67.

219. Robin Baker, Sperm Wars, Basic Books, 1996, p. 38. Baker has contributed several novel findings to this field but some have not survived challenge by other researchers; see Birkhead, as cited, pp. 23–29.

220. W H. James, "The Incidence of Superfecundation and of Double Paternity in the General Population," Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae 42:257–262 (1993).

221. R. E. Wenk et al., "How Frequent is Heteropaternal Superfecundation?" Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae 41:43–47 (1992).

222. Louise Barrett, Robin Dunbar, and John Lycett, Human Evolutionary Psychology, Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 181.

223. Bobbi S. Low, Why Sex Matters, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 80.

224. David M. Buss, Evolutionary Psychology, 2nd ed., Pearson Education, 2004, p. 112.

225. Там же, с. 117.

226. Geoffrey Miller, The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature, Doubleday, 2000.

227. Marta Mirazon Lahr, The Evolution of Modern Human Diversity: A Study of Cranial Variation, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 263.

228. Там же, с. 337.

229. Marta Mirazon Lahr and Richard V. S. Wright, "The Question of Robusticity and the Relationship Between Cranial Size and Shape in Homo sapiens," Journal of Human Evolution 31:157–191 (1996).

230. Helen M. Leach, "Human Domestication Reconsidered," Current Anthropology 44:349–368 (2003).

231. Там же, с. 360.

232. Richard Wrangham, interview, Edge, February 2, 2002, www.edge.org.

233. Allen W. Johnson and Timothy Earle, The Evolution of Human Societies, 2nd ed., Stan ford University Press, 2000.

234. www.who.int/whr/2004/annex/topic/en/annex_2_en.pdf.

235. Derek V. Exner et al., "Lesser Response to Angiotensin-convertingenzyme Inhibitor Therapy in Black as Compared with White Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction," New England Journal of Medicine 344:1351–1357 (2001).

236. Anne L. Taylor et al., "Combination of Isosorbide Dinitrate and Hydralazine in Blacks with Heart Failure," New England Journal of Medicine 351:2049–2057, 2004; Nicholas Wade, "Race-Based Medicine Continued, "New York Times November 14, 2004, Section 4, p. 12.

237. Robert S. Schwartz, "Racial Profiling in Medical Research," New England Journal of Medicine 344:1392–1393 (2001).

238. "Genes, Drugs and Race," Nature Genetics 29:239 (2001).

239. Neil Risch, Esteban Burchard, Elav Ziv, and Hua Tang, "Categorization of Ilumans in Biomedical Research: Genes, Race and Disease," genomebiology.com/2002/3/7/comment/2007.

240. Agnar Helgason et al., "An Icelandic Example of the Impact of Population Structure on Association Studies," Nature Genetics 37:90–95 (2005); Nicholas Wade, "Where Are You From? For Icelanders, the Answer Is in the Genes," New York Times, December 28, 2004, p. F3.

241. Rebecca L. Lamason et al., "SLC24A5, a Putative Cation Exchanger, Affects Pigmentation in Zebrafish and Humans," Science 310:1782–1786 (2005).

242. Noah A. Rosenberg et al., "Genetic Structure of Human Populations," Science 298:2381–2385 (2002).

243. Nicholas Wade, "Gene Study Identifies 5 Main Human Populations, Linking Them to Geography," New York Times, December 20, 2002, p. A37.

244. В американской судебно-медицинской экспертизе у подозреваемого исследуются 13 участков генома и подсчитывается число повторов. Немало людей могут иметь одно и то же число повторов на одном участке. Заметно меньше имеют поровну повторов на двух участках. Вероятность того, что в США найдется два человека, обладающих одинаковым числом повторов на всех 13 участках, столь ничтожна, что набор повторов можно считать неповторимым, исключение — однояйцевые близнецы. (Число повторов на каждом участке — это фактически два числа: одно — повторы в хромосоме, унаследованной от матери, второе — в отцовской, но внутри пары числа часто бывают равные).

245. Nicholas Wade, "For Sale: A DNA Test to Measure Racial Mix," New York Times, October 1, 2002, p. F4.

246. Nicholas Wade, "Unusual Use of DNA Aided in Serial Killer Search," New York Times, June 2, 2003, p. A28.

247. Richard Lewontin, Human Diversity, W. H. Freeman, 1995, p. 123.

248. Statement adopted by the council of the American Sociological Association, August 9, 2002; available on www.asanet.org.

249. American Anthropological Association statement on "Race," May 17, 1998; www.aaanet.org.

250. Quoted by Henry Harpending and Alan R. Rogers in "Genetic Perspectives on Human Origins and Differentiation," Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 1:361–385 (2000).

251. David L. Hartl and Andrew G. Clark, Principles of Population Genetics, 3rd ed., Sinauer Associates, 1997, p. 119.

252. Patrick D. Evans et al., "Microcephalin, a Gene Regulating Brain Size, Continues to Evolve Adaptively in Humans," Science 309:1717–1720 (2005).

253. Nitzan Mekel-Bobrov, "Ongoing Adaptive Evolution of ASPM, a Brain Size Determinant in Homo sapiens," Science 309:1720–1722 (2005).

254. John H. Relethford, "Apportionment of Global Human Genetic Diversity Based on Craniometries and Skin Color," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 118:393–398 (2002).

255. Henry Harpending and Alan R. Rogers, "Genetic Perspectives on Human Origins and Differentiation," 1:380.

256. Анализ, проведенный группой Притчарда, основан на том обстоятельстве, что благоприятные мутации наследуются в составе крупных блоков ДНК, каждый из которых несет индивидуальную «подпись» из ДНК-модификаций. Если ген с полезной мутацией распространяется быстро, то распространяется и блок, следовательно, ДНК на этом участке хромосомы в популяции становится менее разнообразной: все больше особей носят в этом участке хромосомы одинаковую последовательность блоков ДНК. Анализ Притчарда показывает уровни этого разнообразия у тех, кто обладает новой версией гена, и тех, кто не обладает. Малое разнообразие в масштабах популяции считается признаком отбора. Когда ген становится универсальным, разница в вариативности исчезает: все люди носят новый блок. Таким образом тест выявляет только новые мутированные гены, которые еще не стали универсальными, то есть недавно отобранные.

Блоки с мутированными генами Притчард искал в материале, собранном проектом Hap Map у африканцев (нигерийских йоруба), восточных азиатов и европейцев. Для африканских генов время селективного давления определено в 10 800 лет назад, для азиатских и европейских — в 6600 лет назад.

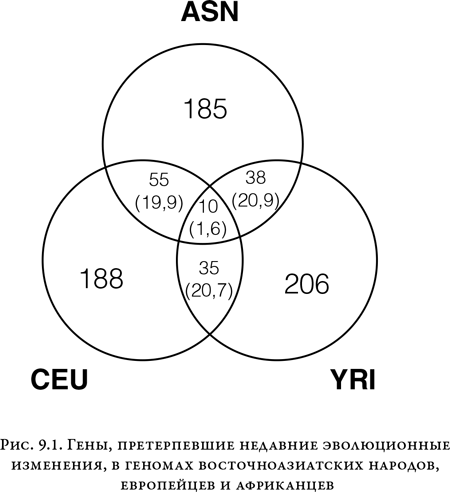

Схема показывает, что у африканцев обнаружено 206 закрепляющихся кодирующих областей, у азиатов — 185 и у европейцев — 188. Лишь небольшая часть закрепляющихся генов совпадает: значит, каждая из популяций эволюционировала независимо от других. Общие для двух рас отобранные гены могут объясняться миграцией или конвергентной эволюцией.

Закрепляющиеся гены разбиваются на отдельные категории. Особенно четко сигнализируют об отборе четыре гена цвета кожи, закрепляющиеся только у европейцев. Другая категория закрепляющихся генов относится к строительству скелета (возможно, это след грацилизации человеческих популяций). Остальные категории: гены детородности, гены вкуса и обоняния и гены, связанные с усваиванием пищи. Две последние группы, вероятно, отражают резкую перемену в рационе, которая произошла после неолитической революции.

Источник: Benjamin F. Voight; Sridhar Kudaravalli; Xiao-quan Wen; Jonathan K. Pritchard. "A Map Of Recent Positive Selection In The Human Genome", PloS Biology 4:446-458 (2006).

Гены, подвергшиеся недавним эволюционным трансформациям в геномах жителей восточной Азии (ASN), европейцев (CEU) и африканцев (YRI).

257. Nicholas Wade, "Race-Based Medicine Continued," New York Times, November 14, 2004, Section 4, p. 12.

258. Jon Entine, Taboo, Public Affairs, 2000, p. 34.

259. Там же, с. 39–40.

260. Jon Entine, "The Straw Man of 'Race,'" World 6I, September 2001, p. 309.

261. John Manners, Kenya's Running Tribe, available online at www.umist.ac.uk.

262. Там же.

263. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, W. W. Norton, 1997, p. 25.

264. Richard Klein, The Human Career, 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 502.

265. Robin I. M. Dunbar, "The Origin and Subsequent Evolution of Language," in Morten H. Christiansen and Simon Kirby, Language Evolution, Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 231.

266. Judges 12:5–6.

267. Denis Mack Smith, Medieval Sicily, Chatto & Windus, 1968, p. 71.

268. William A. Foley, "The Languages of New Guinea," Annual Review of Anthropology 29:357–404 (2000).

269. Jonathan Adams and Marcel Otte, "Did Indo-European Languages Spread before Farming?" Current Anthropology 40:73–77 (1999).

270. Jared Diamond and Peter Bellwood, "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions," Science 300:597–603 (2003).

271. Christopher Ehret, O. Y. Keita, and Paul Newman, "Origins of Afroasiatic," Science 306:1680–1681 (2004).

272. Christopher Ehret, "Language Family Expansions: Broadening Our Understandings of Cause from an African Perspective," in Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew, eds., Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2002, p. 173.

273. Colin Renfrew, Archaeology and Language, Jonathan Cape, 1987.

274. L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press, 1994, pp. 296–299.

275. Там же, с. 299.

276. Marek Zvelebil, "Demography and Dispersal of Early Farming Populations at the Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition: Linguistic and Genetic Implications," in Peter Bellwood and Colin Renfrew, ed., Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2002, p. 381.

277. Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time Depth in Historical Linguistics, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000.

278. Bill J. Darden, "On the Question of the Anatolian Origin of Indo-Hittite," in Great Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language Family, Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph No. 38, Institute for the Study of Man, 2001.

279. Mark Pagel, "Maximum-Likelihood Methods for Glottochronology and for Reconstructing Linguistic Phylogenies," in Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time Depth in Historical Linguistics, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000, p. 198.

280. K. Bergsland and H. Vogt, "On the Validity of Glottochronology," Current Anthropology 3:115–153 (1962).

281. Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson, "Language-Tree Divergence Times Support the Anatolian Theory of Indo-European Origin," Nature 426:435–439 (2003).

282. Peter Forster and Alfred Toth, "Toward a Phylogenetic Chronology of Ancient Gaulish, Celtic and Indo European," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:9079–9084 (2003).

283. Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press 2000, p. 1.

284. Christopher Ehret, "Language and History," in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 272–298; "Testing the Expectations of Glottochronology against the Correlations of Language and Archaeology in Africa," in Colin Renfrew, April McMahon, and Larry Trask, eds., Time Depth in Historical Linguistics, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research 2000 pp. 373–401.

285. Richard J. Hayward, "Afroasiatic," in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 79–98.

286. Christopher Ehret, "Language and History," in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 290.

287. Nicholas Wade, "Joseph Greenberg, 85, Singular Linguist, Dies," New York Times May 15, 2001, p. A23.

288. Joseph H. Greenberg, "Language in the Americas," Stanford University Press, 1987.

289. L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza, The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press, 1994, pp. 317, 96.

290. Там же, с. 99.

291. L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, Eric Minch, and J. L. Mountain, "Coevolution of Genes and Languages Revisited," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89:5620–5624 (1992).

292. M. Lionel Bender, in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 54.

293. Пример взят из Lyle Campbell, Historical Linguistics, MIT Press 1999 p. 111.

294. Richard Hayward, in Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse, eds., African Languages, Cam bridge University Press, 2000, p. 86.

295. Nicholas Wade, "Scientist at Work: Joseph H. Greenberg; What We All Spoke When the World Was Young," New York Times, February 1, 2000, p. F1.

296. Joseph H. Greenberg, Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives, Volume 1: Grammar, Stanford University Press, 2000, p. 217.

297. Joseph H. Greenberg, Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives, Volume 2: Lexicon, Stanford University Press, 2002.

298. Там же, с. 2.

299. Nicholas Wade, "Joseph Greenberg, 85, Singular Linguist, Dies," New York Times, May 15, 2001, p. A23; Harold C. Fleming, "Joseph Harold Greenberg: A Tribute and an Appraisal," Mother Tongue: The Journal VI: 9–27 (2000-2001).

300. Johanna Nichols, "Modeling Ancient Population Structures and Movement in Linguistics," Annual Review of Anthropology, 26:359–384 (1979).

301. Mark Pagel, "Maximum-Likelihood Methods for Glottochronology and for Reconstructing Linguistic Phylogenies."

302. Merritt Ruhlen, The Origin of Language, Wiley, 1994, p. 115.

303. Tatiana Zerjal et al., "The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols," American Journal of Hu man Genetics 72:717–721 (2003).

304. Ala-ad-Din 'Ata-Malik Juvaini, The History of the World Conqueror, trans. J. A. Boyle, Manchester University Press, 1958, vol. 2, p. 594.

305. Nicholas Wade, "A Prolifi c Genghis Khan, It Seems, Helped People the World," New York Times, February 11, 2003, p. F3.

306. Yali Xue et al., "Recent Spread of a Y-Chromosomal Lineage in Northern China and Mongolia," American Journal of Human Genetics, 77:1112–1116 (2005).

307. В северо-западной Ирландии целых 20% мужчин обладают особенным набором мутаций в Y-хромосоме, известным как ирландский модальный гаплотип. Фамилии у многих из них восходят к Уи Нейллам, группе династий верховных королей Ирландии, правивших северо-западом и другими областями страны приблизительно с 600 по 900 г. Имя Уи Нейлл переводится как «потомки Ниалла». Историки были склонны считать их политическим образованием, а патриарха Ниалла Девять Заложников — легендарной фигурой. Генетическое исследование дает четкие доказательства того, что Ниалл Девять Заложников существовал в действительности: это открытие столь же поразительное, как если бы легенды о короле Артуре оказались исторической правдой. Ирландский модальный гаплотип, ярлык потомков Ниалла, чаще всего встречается в северо-западной Ирландии, но кроме того — в ирландской диаспоре: им обладают не менее 1% жителей Нью-Йорка европейского происхождения. Очевидно, не стоит воспринимать слишком скептически слова ирландцев, когда они говорят, что в их жилах течет королевская кровь. Laoise T. Moore et al., "A Y-Chromosome Signature of Hegemony in Gaelic Ireland," American Journal of Human Genetics 78:334–338 (2006).

308. George Redmonds, interview, April 5, 2000.

309. Bryan Sykes, Adam's Curse, W. W. Norton, 2004, p. 7.

310. Bryan Sykes and Catherine Irven, "Surnames and the Y Chromosome," American Journal of Human Genetics 66:1417–1419 (2000).

311. Nicholas Wade, "If Biology Is Ancestry, Are These People Related?" New York Times, April 9, 2000, Section 4, p. 4.

312. Bryan Sykes, Adam's Curse, p. 18.

313. Cristian Capelli et al., "A Y Chromosome Census of the British Isles," Current Biology 13:979–984 (2003).

314. Emmeline W. Hill, Mark A. Jobling, and Daniel G. Bradley, "Y-chromosome Variation and Irish Origins," Nature 404: 351 (2000); Nicholas Wade, "Researchers Trace Roots of Irish and Wind Up in Spain," New York Times, March 23, 2000, p. A13; Nicholas Wade, "Y Chromosomes Sketch New Outline of British History," New York Times, May 27, 2003, p. F2.

315. James F. Wilson et al., "Genetic Evidence for Different Male and Female Roles During Cultural Transitions in the British Isles," Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 98:5078–5083 (2001).

316. Norman Davies, The Isles, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 3.

317. Benedikt Hallgrimsson et al, "Composition of the Founding Population of Iceland: Biological Distance and Morphological Variation in Early Historic Atlantic Europe," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 124:257–274 (2004).

318. Agnar Helgason et al., "Estimating Scandinavian and Gaelic Ancestry in the Male Settlers of Iceland," American Journal of Human Genetics 67:697–717 (2000).

319. Agnar Helgason et al., "mtDNA and the Origin of the Icelanders: Deciphering Signals of Recent Population History," American Journal of Human Genetics 66:999–1016 (2000).

320. Benedikt Hallgrimsson et al., "Composition of the Founding Population of Iceland."

321. Nicholas Wade, "A Genomic Treasure Hunt May Be Striking Gold," New York Times, June 18, 2002, p. F1.

322. Agnar Helgason et al., "A Population-wide Coalescent Analysis of Icelandic Matrilineal and Patrilineal Genealogies: Evidence for a Faster Evolutionary Rate of mtDNA Lineages than Y Chromosomes," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:1370–1388 (2003).

323. M. F. Hammer et al, "Jewish and Middle Eastern Non-Jewish Populations Share a Common Pool of Y-chromosome Biallelic Haplotypes, "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97:6769–6774 (2000).

324. Mark G. Thomas et al., "Founding Mothers of Jewish Communities: Geographically Separated Jewish Groups Were Independently Founded by Very Few Female Ancestors," American Journal of Human Genetics 70:1411–1420 (2002).

325. Harry Ostrer, "A Genetic Profile of Contemporary Jewish Populations," Nature Review Genetics 2:891–898 (2001).

326. Shaye J. D. Cohen, The Beginnings of Jewishness, University of California Press, 1999, p. 303.

327. Denise Grady, "Father Doesn't Always Know Best," New York Times, July 7, 1988, Section 4, p. 4.

328. Yaakov Kleiman, "The DNA Chain of Tradition," www.cohen-levi.org.

329. Karl Skorecki et al., "Y Chromosomes of Jewish Priests," Nature 385:32 (1997).

330. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed, Free Press, 2001, p. 98.

331. Mark G. Thomas et al., "Origins of Old Testament Priests," Nature 394:138–139 (1998).

332. James S. Boster, Richard R. Hudson, and Steven J. C. Gaulin, "High Paternity Certain ties of Jewish Priests," American Anthropologist 111 (4):967–971 (1999).

333. Doron M. Behar et al., "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries," American Journal of Human Genetics 73:768–779 (2003).

334. Nicholas Wade, "Geneticists Report Finding Central Asian Link to Levites," New York Times, September 27, 2003, p. A2.

335. Harry Ostrer, "A Genetic Profile of Contemporary Jewish Populations," 336. Jared M. Diamond, "Jewish Lysosomes," Nature 368:291–292 (1994).

337. Neil Risch et al., "Geographic Distribution of Disease Mutations in the Ashkenazi Jewish Population Supports Genetic Drift over Selection," American Journal of Human Genetics 72:812–822 (2003).

338. Montgomery Slatkin, "A Population-Genetic Test of Founder Effects and Implications for Ashkenazi Jewish Diseases," American Journal of Human Genetics 75:282–293 (2004).

339. Gregory Cochran, Jason Hardy, and Henry Harpending, "Natural History of Ashkenazi Intelligence," Journal of Biosocial Science, in press (2005).

340. Melvin Konner, Unsettled: An Anthropology of the Jews, Viking Compass, 2003, p. 198.

341. Merrill D. Peterson, The Jefferson Image in the American Mind, Oxford University Press, 1960, p. 187.

342. Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, Knopf, 1997.

343. Annette Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, University of Virginia Press, 1997, p. 224.

344. Eugene A. Foster et al., "Jefferson Fathered Slave's Last Child," Nature 396:27–28 (1998).

345. Nicholas Wade, "Defenders of Jefferson Renew Attack on DNA Data Linking Him to Slave Child," New York Times, January 7, 1999, p. A20.

346. Edward O. Wilson, Consilience, Alfred A. Knopf 1998, p. 286.

347. The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, "Initial Sequence of the Chimpanzee Genome and Comparison with the Human Genome," Nature 436:69–87 (2005). 99%-ное совпадение показывает сравнение тех последовательностей ДНК в геноме человека и шимпанзе, которые напрямую соответствуют друг другу. Совпадение уменьшается до 96%, если учесть вставки и исключения, то есть участки ДНК, встречающиеся только в одном из геномов.

348. Louise Barrett, Robin Dunbar, and John Lycett, Human Evolutionary Psychology, Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 12.

349. 349 Mark Pagel, in Encyclopedia of Evolution, p. 330.

350. Sarah A. Tishkoff et al., "Haplotype Diversity and Linkage Disequilibrium at Human G6PD: Recent Origin of Alleles That Confer Malarial Resistance," Science 293: 455–462 (2001).

351. J. Claiborne Stephens et al., "Dating the Origin of the CCR5-A32 AIDS Resistance Allele by the Coalescence of Haplotypes," American Journal of Human Genetics 62:1507–1515 (1998).

352. Alison P. Galvani and Montgomery Slatkin, "Evaluating Plague and Smallpox as Historical Selective Pressures for the CCR5-A32 HIV Resistance Allele," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100:15276–15279 (2003).

353. Hreinn Stefansson et al, "A Common Inversion under Selection in Europeans," Nature Genetics 37:129–137 (2005); Nicholas Wade, "Scientists Find DNA Region That Affects Europeans' Fertility," New York Times, January 17, 2005, p. A12.

354. Yoav Gilad et al, "Human Specific Loss of Olfactory Receptor Genes," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100:3324–3327 (2003).

355. Patrick D. Evans et al., "Microcephalin, a Gene Regulating Brain Size, Continues to Evolve Adaptively in Humans," Science 309:1717–1720 (2005).

356. Nitzan Mekel-Bobrov et al., "Ongoing Adaptive Evolution of ASPM, a Brain Size Determinant in Homo sapiens," Science 309:1720–1722 (2005).

357. Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Random House, 1994.

358. Quoted in Bobbi S. Low, Why Sex Matters, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 57.

359. Elizabeth A. D. Hammock and Larry J. Young, "Microsatellite Instability Generates Diversity in Brain and Sociobehavioral Traits," Science 308:1630–1634 (2005).

360. Richard E. Nisbett, The Geography of Thought, Free Press (2003).

361. Victor Davis Hanson, Carnage and Culture, Doubleday, 2001, p. 54.

362. Nicholas Wade, "Can It Be? The End of Evolution?" New York Times, August 24, 2003, Section 4, p. 1.

363. Bobbi S. Low, Sex, Wealth, and Fertility, in Adaptation and Human Behavior, edited by Lee Cronk, Napeoleon Chagnon and William Irons, Walter de Gruyter, 2000, p. 340.

364. Дело в том, что для производства сперматозоидов или яйцеклеток хромосома, полученная от матери, должна соединиться с соответствующей отцовской. Чтобы объединение прошло успешно, ДНК обеих хромосом должны достаточно полно совпадать по всей длине. Если хромосомы слишком различаются, содержат много несовпадающих блоков ДНК, они не смогут слиться, полноценные сперматозоиды или яйцеклетки не образуются, и особь останется бесплодной. M. A. Jobling et al., Human Evolutionary Genetics, Garland, 2004, p. 434.